Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

Saturday, June 6, 2015

What I'm Watching What I'm Watching: Manhunter

Posted By Ethan de Seife on Sat, Jun 6, 2015 at 9:01 AM

- De Laurentiis Entertainment Group

- William Petersen and Dennis Farina in Manhunter.

Manhunter marks the cinematic debut of the character Hannibal Lecter (spelled here Lecktor, for some reason), the Thomas Harris character whom most movie fans know from The Silence of the Lambs, its sequels or the TV show “Hannibal,” the third season of which premieres this week.

It’s also the third feature-length film directed by Michael Mann, one of the premier American film stylists of the last 30 years. I like all of Mann’s films and TV shows, but I’ve always had a special fondness for Manhunter (as well as for his first feature, Thief, from 1981; and his 1980s TV series “Crime Story”). It’s always satisfying to me when I can, as an adult, revisit a film that I loved when I was a kid and find that it justifies my admiration. This time around, Manhunter accomplished that task easily; if anything, my admiration for the film has increased.

The film is bursting with striking, unforgettable images. One that had hung around in my visual cortex, and was reactivated when I saw the film again, was that of a woman lying atop a sedated tiger (below). I’d forgotten the narrative context for this incredible image, but the image itself never left my memory.

- De Laurentiis Entertainment Group

- One of the strangest and most memorable images in Manhunter.

Another gorgeous image, from early in the film, shows actors William Petersen and Dennis Farina sitting on a driftwood log beside the ocean. (It's the image at the top of this page.) It’s a simple, lovely composition that, it turns out, possesses a fair amount of narrative significance.

For one thing, the actors barely move; with that stillness and the idyllic setting, Mann creates a sense of serenity. The stability and peace of this scene, though, are soon undercut by the horrific nature of the crimes that Will Graham (Petersen) will begin investigating.

As well, the blocking in this shot is somewhat unusual, in that the two men are having a conversation while facing away from each other. The composition hints at the tension between the two men that will soon be unleashed by their pursuit of Dollarhyde. Though placid on the surface, this shot is actually somewhat ironic, as it suggests one of the sources of tension that will violently disrupt both men’s lives.

click to enlarge

The tiger scene is striking even without full narrative justification; the beach scene is striking for its ironic undercutting of its apparent serenity. The next step in this progression would be to find a shot or scene that uses striking visuals to convey important narrative information. This is a straightforward task, as Manhunter is replete with scenes of remarkable and sophisticated visual storytelling. Films of its genre, the policier, typically rely on conversations to advance the narrative: between cop and cop, between cop and criminal, between criminal and victim, etc. Manhunter has plenty of such scenes, but the truly impressive parts of the film are those that advance the story by strictly visual means.

- De Laurentiis Entertainment Group

- A gorgeous, symmetrical composition from Manhunter.

The scene I want to focus on is a gorgeous, gruesome one in which we learn the fate of tabloid reporter Freddy Lounds (Stephen Lang), who has been collaborating with Graham in the latter’s investigation. The narrative situation preceding this scene is that Dollarhyde (a serial killer who’s been dubbed “The Tooth Fairy” by Lounds’ newspaper, The National Tattler) abducts Lounds for his involvement with Graham. Dollarhyde, after forcing Lounds to read a statement, savagely kisses/bites him on the face. The first half of the clip below shows the last moments of this scene, which ends with a long shot of Dollarhyde’s home as Lounds’ scream reverberates into the night. The statement that Dollarhyde forces Lounds to read includes a line to the effect that the kidnapper promises to be relatively merciful to his victim, though we don’t know exactly what that means. Given Dollarhyde’s psychosis, it may not be much of a promise at all.

We see only the back of the attendant’s head, a curious way to introduce a character. He hears a noise behind him and turns around; detecting nothing, he turns back to his newspaper. A couple seconds later, we get a delayed point-of-view shot of the ramp that extends upward behind the attendant; at the top, we see reflected on its far wall a glowing orange light that seems to increase in intensity. The image is accompanied by an unidentifiable sound of mechanical or automotive origin, and we’re encouraged to think that both the light and the sound have been produced by an approaching car — the kind of thing one would expect to witness in a parking garage.

Still, the attendant senses that something is awry, and turns back again. As he’s turning, a mechanical, squeaking sound emerges from the mix and increases in volume, and we hear a kind of whooshing noise. Both are soon overwhelmed by the scream of the attendant, who gets up and runs toward the Corvette, terrified of something that we cannot yet see. The last shot in the scene is its most horrific and narratively important: It shows a flaming human figure strapped to a wheelchair that is headed down the ramp, directly toward the attendant’s chair.

- De Laurentiis Entertainment Group

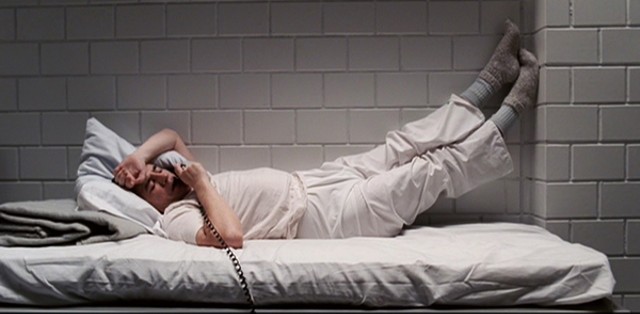

- Bryan Cox as Hannibal Lecktor in Manhunter.

Not a word is uttered in this scene (the attendant’s nonverbal scream doesn’t count!), but words are not needed because the visuals (and the soundtrack), so strong and memorable on their own, do a fine job of conveying all the story information we need. Simply placing the Tattler’s name on the booth tells us where the scene is unfolding. The fact that Lounds’ car is the only one in the garage suggests two things: that this scene probably takes place in the middle of the night, and that Lounds may still be in Dollarhyde’s captivity. The glowing orange light lets us understand exactly what’s on the attendant’s mind: The light and the sound are probably coming from a passing car; not a big deal. Though we can’t yet see what he sees, the shot of the attendant screaming in fear tells us that something horrible is happening. And the final shot of the burning human figure in the wheelchair reveals the scene’s most important pieces of story information: The burning man is Lounds, who may or may not still be alive; and Dollarhyde’s idea of mercy is out of whack with the conventional definition of the term. This is a very sick and dangerous man.

As I say, this remarkable scene is just one of many in which Mann conveys story information with powerful and unusual visuals. I think I’ll watch Manhunter again soon, so impressed am I by its visual design. Honestly, I want nothing else of the films that I watch.

- De Laurentiis Entertainment Group

- Thanks, Internet Rando, for this GIF.

Tags: film, movie, what i'm watching, manhunter, michael mann, visual design, narrative, policier, hannibal lecter, silence of the lambs, Image, Video, Web Only

Comments

Comments are closed.

Since 2014, Seven Days has allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we’ve appreciated the suggestions and insights, the time has come to shut them down — at least temporarily.

While we champion free speech, facts are a matter of life and death during the coronavirus pandemic, and right now Seven Days is prioritizing the production of responsible journalism over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor. Or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.

Related Stories

About The Author

Ethan de Seife

Bio:

Ethan de Seife was an arts writer at Seven Days from 2013 to 2016. He is the author of Tashlinesque: The Hollywood Comedies of Frank Tashlin, published in 2012 by Wesleyan University Press.

Ethan de Seife was an arts writer at Seven Days from 2013 to 2016. He is the author of Tashlinesque: The Hollywood Comedies of Frank Tashlin, published in 2012 by Wesleyan University Press.