Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

-

News

Middlebury College President Patton to Step Down…

-

News

Overdose-Prevention Site Bill Advances in the Vermont…

-

Housing Crisis

'We're Leaving': Winooski's Bargain Real Estate Attracted…

- Aggressive Behavior, Increased Drug Use at Burlington's Downtown Library Prompt Calls for Help City 0

- An Act 250 Bill Would Fast-Track Approval of Downtown Housing While Protecting Natural Areas Environment 0

- Through Arts Such as Weaving, Older Vermonters Reflect on Their Lives and Losses This Old State 0

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

Becoming Americans: New Vermonters Recall Their Pathways to Citizenship

Published November 29, 2017 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated December 26, 2017 at 4:06 p.m.

click to enlarge

- Matthew Thorsen

- Clockwise from top left: Faridar Ko, Ahmed Alsaeedi, Issouf Ouattara, Marta Ceroni (with her dog Frida) and Hameda Hinkle

Hameda Hinkle might not have become a United States citizen this year if it weren't for President Donald Trump. When he signed his executive order of January 27, restricting entry to the U.S. for nationals of seven predominantly Muslim countries, the South Burlington resident was alarmed.

Hinkle is a native of South Africa — not a country named in the order, but she's a Muslim from a region with a sizable population of that faith. "Maybe it's just a matter of time [before] he bans people from Cape Town," she thought.

Read their stories:

More:

Hinkle had been living in America since marrying a U.S. citizen in 2003, but the task of applying for her permanent resident card, or green card, was so arduous that she put off taking the next step, she said.

But when even permanent residents were denied reentry to the U.S. in the initial wake of the travel ban, Hinkle decided it was time to become a naturalized U.S citizen.

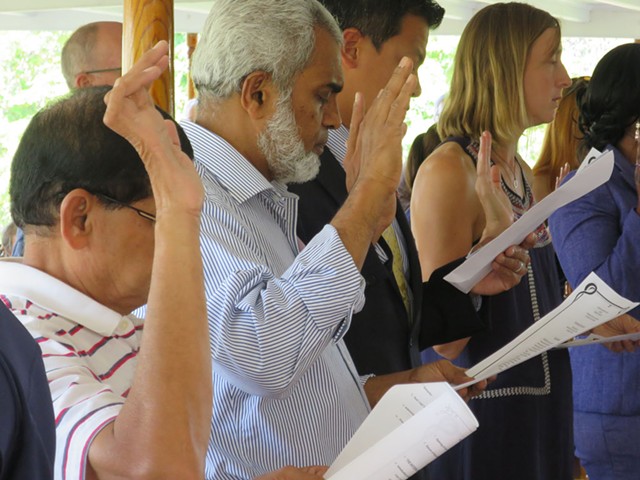

On September 18, Hinkle joined 17 other people from 14 countries to take the oath of allegiance aboard the steamboat Ticonderoga at Shelburne Museum, while about 100 family members, friends and representatives of Vermont's congressional delegation looked on. The naturalization ceremony was part of a weeklong celebration of Constitution Week, when 30,000 new citizens were welcomed at more than 200 ceremonies across the U.S., according to U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services.

click to enlarge

- Matthew Thorsen

- Judge Sessions congratulates a newly naturalized American aboard the Ticonderoga steamboat at Shelburne Museum this September.

Some of them shared Hinkle's motivation. The Trump administration's measures to restrict immigration have had an unintended consequence: Green card holders such as Hinkle are now taking steps to ensure that their future is secured through naturalization.

"Since Trump's election, more people have felt generally anxious and uncertain, and they've been propelled to become citizens," said Michele Jenness, the legal services coordinator at the Association of Africans Living in Vermont.

To be eligible for citizenship, a green card holder must typically have been in the U.S. for at least five years. About 13.2 million permanent green-card-holding residents lived in the U.S. in 2014, and 8.9 million of them were eligible for naturalization, according to the most recent data from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security. In 2015, about 1.05 million people became lawful permanent residents of the U.S.

Data from USCIS show an 8 percent increase in naturalization applications in the three quarters that ended June 30, 2017, compared with the same period the previous year. Still, for the majority of America's 11 million undocumented immigrants, including migrant farmworkers in Vermont, the pathway to citizenship is still elusive.

Since entering office, Trump has made good on his campaign promise to adopt a tough stance on immigration. He rescinded the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, slashed the refugee-arrivals cap from 110,000 last year to a historic low of 45,000 and repeatedly pledged to build a wall along the border with Mexico to prevent undocumented people from entering the U.S. Earlier this month, the administration ended the Central American Minors refugee program, designed to help young people in El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras rejoin their families in the U.S.

Recent events could compromise yet another pathway to citizenship. On October 31, Sayfullo Saipov, who had emigrated from Uzbekistan, killed eight people in Manhattan in a terrorist attack with a pickup truck. When it came to light that Saipov had won his green card through the diversity immigrant visa lottery, Trump called on Congress to kill the program.

Winning the green card lottery is one of the fastest and easiest routes to permanent residency — for a lucky few. In 2015, more than 14 million people applied for the 50,000 diversity visas issued annually. Applicants need only a high school education or two years of work experience.

The program was introduced in 1995 to diversify the U.S. immigrant population by granting legal permanent residency to people from countries with historically low migration rates to the U.S. Whether it still fulfills that aim is debatable, Burlington immigration lawyer Leslie Holman suggested, now that applications must be submitted online: "Many of the underrepresented countries are the developing countries without [that] technology," she said.

While the diversity visa lottery is a long shot, prospective immigrants can take several other paths to obtain legal permanent residency and then — if they're eligible — apply for citizenship.

Family-sponsored immigrants, such as Hinkle, made up the largest group of those who became legal permanent residents in 2015. The second-largest consisted of refugees and asylees, people who fear persecution in their home country.

The third-largest group consists of people who came to the U.S. on employment-based immigrant visas. Five categories of workers include outstanding researchers and immigrant investors who, through the EB-5 program, offer development funds for projects such as the ones at Jay Peak Resort.

No more than 50 visas are granted annually under the Special Immigrant Visa program. This special, tiny program recognizes the contributions of Afghan and Iraqi translators or interpreters who worked directly with U.S. armed forces or at the U.S. embassies in Kabul and Baghdad.

While several other pathways to citizenship exist, family- or employment-based routes and refugee and asylee status together accounted for 92.8 percent of the new permanent residents in 2015.

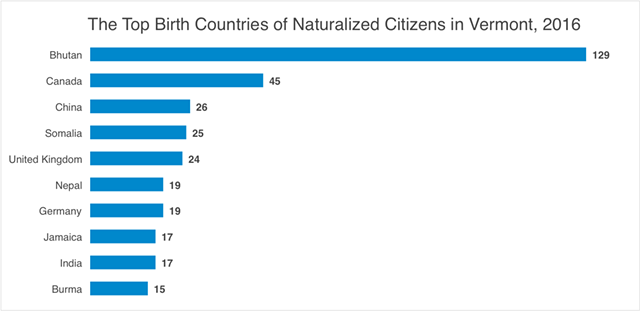

In Vermont, 589 individuals were naturalized in 2016, according to the Department of Homeland Security. The top three countries of origin were Bhutan, Canada and China.

Before administering the oath of allegiance at Hinkle's September naturalization ceremony, U.S. District Court Judge William K. Sessions III acknowledged that "there may be sadness" in the new citizens as they pledged their "complete allegiance to the United States, to the exclusion of all other countries and all other governments.

"If there is true reluctance in any of you," he continued, "then you should withdraw your application and give it due consideration."

While most naturalization ceremonies are festive occasions, some new citizens find them bittersweet, said Jenness of AALV. Though it may seem incongruent with the oath of allegiance, U.S. law doesn't require an individual to choose one nationality over another. Some other countries don't recognize dual citizenship, however. Most of Jenness' clients — asylum seekers and refugees — never wanted to renounce their foreign citizenship, she said.

"A lot of these people never decided to leave their country. They were expelled; they were forced to flee for their lives, the safety of their children," she said. "Giving all that up is like closing a door to your past."

For Hinkle, the ceremony was a less fraught occasion. USCIS commemorated her experience when it tweeted a photo of her and her two young children. A week after the ceremony, Hinkle's colleagues at Keurig Green Mountain gave her a cake that had layers colored red, white and blue, decorated with a South African flag made from marzipan on top.

While the official pathways to American citizenship are finite, the emotional pathways are not; there are as many stories of becoming a citizen as there are individuals. Seven Days talked with four Vermonters and a woman from New Hampshire, representing a range of routes to the green card, about why and how they sought to become American.

"I'm glad I'm here."

Hameda Hinkle, South Africa

Two American flags hang on a wall in Hameda Hinkle's house in South Burlington. One was a gift from her sister, while the other is a souvenir from her naturalization ceremony two months ago.

Now that she's a citizen, she has more protection and rights, Hinkle said: "I can vote. I'm not going to get kicked out of the country."

Hinkle traveled to Virginia from South Africa in late 2002 to visit her sister on a visitor visa. A couple of months into her stay, she met her future husband at a campfire. In April of the following year, they got married, and she moved to New York City, where he lived.

While some people might hire an immigration lawyer, Hinkle did the paperwork for her green card on her own. "I worked in a bank for seven years in South Africa," she said. "Forms aren't foreign to me."

Because she was applying for permanent residency based on her marriage to a U.S. citizen, Hinkle had to supply extensive documentation to prove that the marriage was the real deal. To establish that she and her husband really lived together, she made copies of their pay slips, junk mail, telephone bills, car loan statements, joint homeowner's policy and life insurance policies with each other as beneficiaries. She included their wedding photos, holiday itineraries and notarized affidavits from friends to attest to their relationship and marriage.

The couple also had an interview with USCIS at the Jacob K. Javits Federal Building in downtown Manhattan. Hinkle described the experience as "nerve-racking," because her interviewer "could just decide no" and reject her application.

When Hinkle got her green card in 2003, it was a conditional one, because she had married less than two years after she entered the country. She applied to remove the conditions on her residence two years later and received her green card in 2006.

When it was time to renew her green card in 2016, Hinkle and her family were living in Vermont. She and her husband had drifted apart in the interim, she said, and Hinkle began to think seriously about applying for citizenship to secure her future. Trump's travel ban spurred her to act.

To prepare for her naturalization interview, Hinkle downloaded the civics test app on her phone. During the test, an interviewer asks up to 10 out of 100 possible questions. The applicant needs to answer six correctly.

Would you pass?

Today, Hinkle has dual nationalities. Though she's in divorce proceedings, she plans to stay in the U.S. so that her kids can be close to their father. South Africa has "changed so much" since she left, Hinkle added, noting that her hometown is facing a severe water shortage. "They have it tough; I'm glad I'm here."

"I just wanted [to be] somewhere that's different."

Ahmed Alsaeedi, Iraq

Ahmed Alsaeedi had always planned to leave Iraq as soon as he got his visa to immigrate to the U.S. But when it finally happened, he found himself waiting for two months.

"Once you really think about it, there are stuff you have to do," he said. That included making sure his college transcripts were translated and notarized.

He also had mixed emotions. "It all hits you at the same moment," Alsaeedi recalled, "leaving family and friends, going to a new life."

Alsaeedi grew up in the 1990s, when his country was under economic sanctions imposed by the United Nations Security Council. "Iraq was very isolated," Alsaeedi said. "I just wanted [to be] somewhere that's different."

In 2007, four years after the Iraq War broke out, Alsaeedi began working as an interpreter for the U.S. Army. He was stationed in the western part of the country, where he worked for the U.S. military police. He lived in Iraqi police stations and went patrolling with both Iraqi and U.S. forces. Later, in 2010 and 2011, he was deployed with a U.S. field artillery advisory team.

Many Iraqis saw interpreters as traitors, he said: Consequently, "a lot of them were shot, killed and kidnapped." He was willing to take those risks because the job offered him the possibility of immigrating to the U.S.

Alsaeedi applied for the visa in 2010, gathering required documentation such as a certificate to prove he had never committed a crime, and another to establish that his parents were Iraqi nationals.

After submitting his paperwork and being interviewed, Alsaeedi waited more than a year for an outcome. For six months, he continued to work for the U.S. Army, but "You don't know if you want to commit to something long-term in Iraq ... It's like your life is hanging," he said.

In November 2012, Alsaeedi left his hometown of Baghdad to start a new life in Vermont. A Bhutanese family hosted him for two weeks after his arrival. His brother, who had also worked as an interpreter, joined him in Vermont last year through the same visa program.

Trump's executive order of January 27 originally applied to holders of the Special Immigrant Visa, barring them from entering the U.S., but it was amended in February on the Pentagon's recommendation.

That same month, U.S. Congressman Peter Welch (D-Vt.) brought Alsaeedi as his plus-one to Trump's first congressional address. Welch's aim was to protest the executive order, which included a temporary suspension of the refugee resettlement program. For Alsaeedi, that restriction hit close to home. His parents and sister left Iraq in 2014 for Turkey, where they've been granted refugee status by the United Nations high commissioner for refugees.

Now that Alsaeedi has been in the U.S. for five years, he's eligible for naturalization. "When I get my citizenship, I'd be able to travel to more places," he said. "I want more opportunities."

He'd also be able to petition for his parents and sister to join him in Vermont. But that option presents the family with a dilemma: Only Alsaeedi's parents could be admitted under the "immediate relatives of U.S. citizens" category. As a sibling, his sister would have to wait at least 10 years for a "family-sponsored preference" visa. To avoid that separation, Alsaeedi said, the family has decided to try their luck in the refugee resettlement program instead.

Alsaeedi's family's quest illustrates the tricky choices that selecting a path to citizenship can entail. "They'd have more chances coming as a group, all three of them, through the United Nations' refugee process than me applying for them as a citizen," said Alsaeedi.

"The land belongs to Native Americans."

Marta Ceroni, Italy

Since Milan-born Marta Ceroni became a naturalized U.S. citizen in April 2016, she's been thinking deeply about what her new status means.

"Am I more of an owner of this country than I was before becoming a citizen?" she recalled asking herself a day after her naturalization ceremony, while walking her dog in Norwich, where she works at the nonprofit Academy for Systems Change.

The answer was clear, she said: "No, the land belongs to Native Americans."

Ceroni, 48, described her immigration story as part of the "brain drain" from Italy more than 20 years ago. Her journey is interwoven with bureaucratic red tape and personal relationships, she said.

After getting her PhD in forest ecology from the University of Parma, Ceroni came to the U.S. in April 1997 to join her then-husband. He had left Italy the previous year to work at the University of Maryland on a J-1 nonimmigrant visa, which is issued to individuals who take part in work- and study-based visitor-exchange programs.

Moving to the rural Chesapeake Bay area gave her culture shock, Ceroni recalled. She had few friends and missed the social life that she had enjoyed in Parma. Tensions arose in her marriage, too, she said, when she had trouble finding a job. When she eventually got a position as an assistant research scientist at the University of Maryland, in 1998, Ceroni began contributing toward the household income, she recalled.

But she had to relinquish that job just a few months later, when her spouse received the opportunity to apply for an H-1B visa, a nonimmigrant visa for foreign employees in a specialty occupation. As his immediate family member, Ceroni, too, got a new visa, the H-4. At that time, holders of that particular visa weren't allowed to work.

Ceroni continued to volunteer and apply for grant funding until, two years later, she was able to get her own H-1B visa through the University of Maryland. The school handled the paperwork, she said. But she had to prepare a dossier of documents and letters of support from her colleagues and supervisors in Italy and the U.S.

As with the diversity visa, demand for the H-1B visa exceeds supply. In April, USCIS said it had received 199,000 H-1B petitions; the cap is 85,000.

Getting her own H-1B visa changed her life, Ceroni said. With double income, the couple was able to buy a car and a small house. It was "sort of a mini American dream," she continued.

In 2002, they moved to Vermont, where UVM sponsored Ceroni's husband for a green card. As part of the application, he had to prove that he was making unique contributions to his field and that a U.S. citizen couldn't fill his position. When he got his green card in 2005, as his family member, she got one, too.

Ceroni went on to start the Vermont Immigrant Voting Alliance to advocate for voting rights for noncitizen residents. The group disbanded after press coverage of a mock election it staged in 2007 generated vitriolic reactions, Ceroni said.

As a result of the 2008 financial crisis, she left her research position at UVM's Gund Institute for Environment after funding ran out. In 2009, she separated from her husband.

Though she was eligible for citizenship in 2010, Ceroni waited six more years to apply. In the interim, she moved to New Hampshire, where she found a community of activists who shared her passion, she said. When 2016 rolled around, she wanted to raise her voice in support of renewable energy and protest new fossil fuel infrastructure; being a citizen would make it safer to participate in rallies, she said. "There's a lingering fear when you're not secured in your immigration status," she explained. And she wanted to vote in the November presidential election.

But there was also a part of her that resisted becoming a "citizen of a country that does so many things wrong, that I totally disagree with, starting with the death penalty," Ceroni said.

Though she's now a naturalized U.S. citizen, Ceroni said she'll never be fully integrated and doesn't have strong connections to any particular country.

But one thing she's keen on pursuing is getting "permission" from Native Americans to inhabit their land. She described herself as looking into their traditions and "timidly getting close" to their culture. "Naïvely, I was hoping for a blessing," she said of her interactions with Native Americans, who were wary of her overtures.

She realized that her desire to feel a sense of belonging was "self-serving and self-centered," she said, acknowledging that Native Americans' wounds of dispossession and betrayal are deeper than hers.

Indeed, in Ceroni's view, mindfulness of indigenous Americans is what's missing from the U.S. naturalization ceremony. "When we immigrants come to this country, there should be some recognition ... of the views of the native population," she said.

"The dream ... was to look for opportunities."

Issouf Ouattara, Burkina Faso

For Issouf Ouattara, the third time was the charm when he applied for the diversity visa — the program that Trump now wants to kill. In the spring of 2009, the Burkina Faso man learned that his application had been selected for green card processing.

Ouattara had first applied for the visa in 2006, when he was 29, and again in 2007. But he was motivated to keep trying. "The dream of every African from Burkina Faso, at some point, was to look for opportunities, and we talked about ways to get better education and jobs," he recalled.

A legal adviser for a bank in his native country, Ouattara said he felt stressed because his employment contract was subject to renewal every six months. "It was never stable," he said. "You have to know somebody to get a job." Watching the education system in Burkina Faso decline, he worried about his children's prospects.

So, in the fall of 2008, together with a group of friends, Ouattara tried his luck for the third time. Applying for the diversity visa was relatively straightforward, he recalled; the trickiest part was uploading a photograph with the requisite dimensions.

Ouattara was the only successful applicant among his friends. After completing interviews, background checks and medical exams, he immigrated to the U.S alone in October 2010, determined to build a new life for himself before bringing his wife and two children over.

Ouattara had initial difficulties adjusting to life in the U.S., he admitted. "When I was in Burkina Faso, I was kind of a boss there. I had a big car with a driver," he said. He also had undergraduate and graduate degrees in business law. In Vermont — where he moved after getting a tip about a fellow countryman who would help him find housing — his first job was machine operation for Winooski soap manufacturer Twincraft Skincare.

Ouattara didn't spend time feeling sorry for himself or regretting his decision to immigrate. "I was so focused," he recalled. "I had to find a place to stay. I had to be able to [rise] through the ranks so that my income will allow me to bring my family here."

Ouattara worked for a number of companies before he found a job with the University of Vermont's custodial services, where he's now a senior supervisor. He gained U.S. citizenship in 2015; a year later, his wife and two sons joined him in Vermont.

With a tinge of pride, Ouattara said that one of his sons has taken to correcting his English pronunciation. "I can see a bright future for him," he said, beaming.

While he's confident that his sons will acculturate and thrive, Ouattara said he'll always feel like a stranger in the U.S. "If you take a stone or a piece of wood and put it in water, it will never become a fish," he said.

Having brought his family to Vermont, Ouattara now has new goals. "I also want to go back to law school," he said. He's currently a master's of public administration candidate at UVM.

Eventually, Ouattara wants to return to Burkina Faso, open his own business and help with regional development efforts, using the knowledge he's gained from his U.S. education. "I will always be able to forgive myself if I happen to go back home with empty pockets," he said. "But I will never forgive myself if I have to go with an empty head."

"Now I feel safe."

Faridar Ko, Burma (now Myanmar)

When Faridar Ko arrived in Vermont as a teenager, she wasn't expecting her new neighbors to be friendly.

During a pre-resettlement cultural orientation course, Ko learned that, in the U.S., it isn't considered polite to pick flowers in someone else's yard. "I was amazed by that," she recalled. Born in Burma, Ko grew up in a refugee camp in Thailand where, she continued, it wasn't unusual for neighbors to share such things.

Ko learned a lot about Americans by the time she and her family left the camp in June 2008. She also got a new name.

Burmese people don't have first or last names in the Western sense, so when her family went through the resettlement process, officials changed their names to conform to Western nomenclature. Her father, originally Sako, became Sa Ko, and Faridar Be became Faridar Ko.

Ko has few memories of her native country. It wasn't until she was in high school, she said, that she learned more about the history of her Burmese Muslim family.

That history was one of genocide and racism, she said, decades before the recent exodus of the Rohingya Muslims from Rakhine State in Myanmar gained international attention. "The Burmese army came and kicked us out of the village," Ko said, recounting what her elders have told her.

In the mid-2000s, the United Nations high commissioner for refugees offered Ko and her family the opportunity to be resettled in the U.S. They went through two rounds of interviews, each of which lasted close to three hours. They were asked the same questions several times, she added.

Looking back, Ko believes the interviewers were checking for the consistency of the family's answers. Applicants who said they had worked for any army, she continued, were rejected.

Once they had completed their medical examination, Ko and her family waited to learn of their resettlement date. Worried about missing their window to depart, they seldom left their refugee camp, even for necessities. "Sometimes we didn't have any food," she said.

In 2008, Ko and her parents and four siblings were among the 60,191 refugees resettled in the U.S. While obtaining refugee status is a timeworn path to citizenship, numbers and national origins fluctuate with U.S. policy and conflicts around the world. In that year, Burma was the top country of national origin for refugees. In the 2017 fiscal year, it was the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Ko graduated from Winooski High School in 2012. Now 24, she has been working at her alma mater as a home-school liaison for two years.

While Ko and her family didn't have a say in deciding where in the U.S. they'd be resettled, they've made Vermont their home. Some others who were resettled in Vermont have chosen to move on. In the past year, she said, five Burmese Muslim families have moved to Utica, N.Y., where there's a larger community and an Islamic school.

Though Ko was undecided about becoming a citizen for many years, Trump's election motivated her to take steps toward naturalization. Her son, Samin O Lar, is already American because he was born in the U.S.

In July, Ko and her husband submitted their applications. Next, they had to provide their fingerprints, photographs and signatures at an application support center in St. Albans, where they got a study booklet to help them prepare for the English and civics test. The couple passed their naturalization interview in October.

On December 5, Ko and her husband will take the oath of allegiance at the Vermont Supreme Court in Montpelier. "Now I feel safe," said Ko.

Naturalization Oath of Allegiance to the United States of America

I hereby declare, on oath, that I absolutely and entirely renounce and abjure all allegiance and fidelity to any foreign prince, potentate, state, or sovereignty, of whom or which I have heretofore been a subject or citizen; that I will support and defend the Constitution and laws of the United States of America against all enemies, foreign and domestic; that I will bear true faith and allegiance to the same; that I will bear arms on behalf of the United States when required by the law; that I will perform noncombatant service in the Armed Forces of the United States when required by the law; that I will perform work of national importance under civilian direction when required by the law; and that I take this obligation freely, without any mental reservation or purpose of evasion; so help me God.

(Source: uscis.gov)

How Well Would You Do on the U.S. Citizenship Test?

The U.S. citizenship test is administered orally by a U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services officer. The test is comprised of 10 questions selected from a pool of 100 possible questions. Applicants must correctly answer 6 out of 10 to pass.

The original print version of this article was headlined "Becoming Americans"

Related Stories

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

More By This Author

About the Artist

Matthew Thorsen

Bio:

Matthew Thorsen was a photographer for Seven Days 1995-2018. Read all about his life and work here.

Matthew Thorsen was a photographer for Seven Days 1995-2018. Read all about his life and work here.

Comments

Showing 1-1 of 1

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.

- 1. Amalia Angulo’s Drawings at Kishka Gallery Suggest and Question a 'Peaceable Kingdom' Art Review

- 2. Video: Visiting the Wind Phone at the Lanpher Memorial Library in Hyde Park Stuck in Vermont

- 3. Bianca Stone Named New Vermont Poet Laureate Poetry

- 4. STRUT! Fashion Show Returns After Four-Year Hiatus Culture

- 5. Woodstock Poetry Festival Replaces Bookstock Books

- 6. The Magnificent 7: Must See, Must Do, May 1-7 Magnificent 7

- 7. Shaina Taub's 'Suffs' Earns Six Tony Nominations, Including Best Musical Performing Arts

- 1. How a Vergennes Boatbuilder Is Saving an Endangered Tradition — and Got a Credit in the New 'Shōgun' Culture

- 2. Video: The Champlain Valley Quilt Guild Prepares for Its Biennial Quilt Show Stuck in Vermont

- 3. Waitsfield’s Shaina Taub Arrives on Broadway, Starring in Her Own Musical, ‘Suffs’ Theater

- 4. This Manchester Center Family Is a National Show Horse Powerhouse Animals

- 5. Video: 'Stuck in Vermont' During the Eclipse Stuck in Vermont

- 6. Pet Project: Introducing the Winners of the 2024 Best of the Beasts Pet Photo Contest Animals

- 7. Vermont Poet Sydney Lea on His New Collections of Verse and Prose Books