click to enlarge

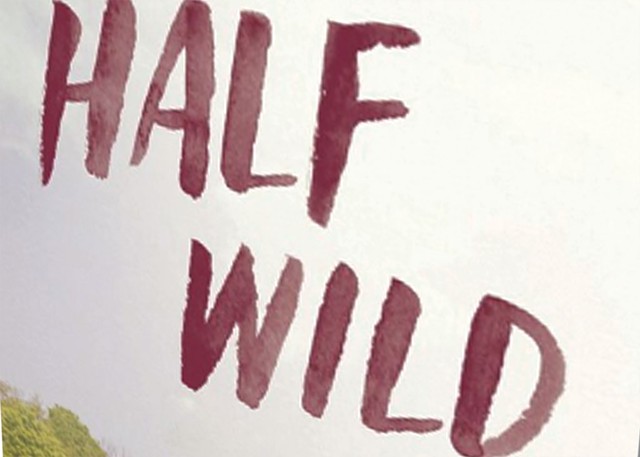

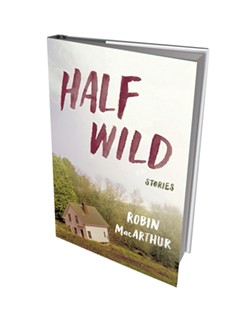

"I thought then how she looked like she was of this place, like she was some kind of creature or tree that had grown here." That's a man's description of the woman he loves in "Maggie in the Trees," a story from Half Wild. The evocative phrase "of this place" works just as well to describe this debut collection from Robin MacArthur of Marlboro.

The author is a third-generation Vermonter, and her work displays many of the traits typically associated with Green Mountain fiction: an intense, lyrical engagement with rural landscapes; an elegiac tone; a recurring motif of the tension between outsiders and those who are "from here." Yet nothing is tired or overly familiar about this glowing collection. Partly through the broad range of her sympathies, partly through the impressionistic sorcery of her prose, MacArthur transcends the traditions of "place-based" fiction to create something new.

click to enlarge

- Half Wild: Stories by Robin MacArthur, Ecco, 224 pages. $24.99.

Most of these 11 stories are told in first person. Their protagonists are (mostly) women and men, ranging in age from teen to elderly. Some are "from here" and others not; some dwell in McMansions and others in trailers on the edge of crumbling farmsteads. Yet they all share a place — the rural environs of "Whiskey Mountain," where "some poor fella died making moonshine," says Maggie in the story that bears her name. According to local legend, it was the craving for more and more that killed him: "Can you imagine? A place named after that kind of wanting?"

MacArthur's characters all feel a "wanting." Some yearn for sex, adventure, escape. For others, the landscape itself stirs a deep ache in the soul. In "The Heart of the Woods," the wife of the town's biggest real estate developer visits her dad, a hard-drinking logger wedded to his rugged life in the forest. Over the course of a long, boozy evening, she feels "the dangerous and frightening pull of some new, or old, kind of life — drunk, hopeless, pine-pitched — calling."

MacArthur makes us feel the call of the wild, and the ties to the land that make old farmsteaders reluctant to sell. But she doesn't present allegiance to the land as a simple or unambiguous good. In "Where Fields Try to Lie," a middle-aged urbanite returns to his ancestral farm, "the place that will not let me be." Yet he has no "romantic dream of returning to the land." For this narrator, home is steeped in memories of a harsh life that he escaped only after paying, as we learn, a terrible price.

MacArthur's characters include natives whose forebears go back many generations, newcomers and a third class of people who aren't so often portrayed in fiction — the back-to-the-landers' grown children. In "The Women Where I'm From," an urban dweller returns to Vermont to care for her sick mother, who had arrived in a more idealistic time, decided to milk goats and never left. Struggling with her own feelings of rootlessness, the daughter wonders why she chose to flee from her mother's Eden. "I don't hate it here; I hate what happens to me when I am here," she tells us. "I hate the way it draws me in. The way it leads to nowhere but itself."

Indeed, the landscape of these stories often feels like a labyrinth coiled in on itself, a place of magical borders that only some can cross. Yet it remains connected to the outer world and the rumblings of wider conflicts, as MacArthur reminds us in "God's Country."

That title is ironic: An elderly woman suspects her beloved grandson has begun hosting a white supremacy group in her barn. Torn between kinship and a sense of justice, she finds herself remembering the first time she faced such a dilemma: in her youth, when a nascent romance collided with the area's then-flagrant racial prejudices. For some people, MacArthur reminds us in this un-preachy story, being "from here" can become a pretext for hating those one classifies as intruders.

These brief stories, many of them in present tense, have a restless flow that makes them as hypnotic as the places they describe. Few feature much action, and some are essentially vignettes, such as "Creek Dippers" (see sidebar), yet it's hard to put any of them down in the middle.

All of the stories showcase MacArthur's knack for indelible, almost Proustian sensory description. The daughter in "The Heart of the Woods" remembers her father by his "familiar earthy whiff of hemlock sap and cigarette smoke and clean sweat." In "Where Fields Try to Lie," the narrator "breathe[s] in the scent of mud, that dank and harrowing smell that wants, every year, and with such determination, to break things open."

Just as the land's illusion of permanence coexists with its seasonal rupture and destruction (and its human development), so the desire to stay or go, to log or farm or to escape the stink of mud and manure forever, can coexist in a single family. Yet all MacArthur's characters have something in common: The land speaks to them, "pulls" them. Inseparable from their memories, it will always belong to their dreams.

These stories could help redefine "Vermont fiction" for anthologists to come, in that they effortlessly marry old-timer tropes with contemporary ones. After all, is the hard-drinking logger any more the epitome of Vermont than the opiate addict who lives in a trailer with her grown daughter, watching reruns of "Twin Peaks"? Readers of this stunning collection may find that MacArthur's places and people haunt their dreams, as well.

From "Creek Dippers" in Half Wild

My mother and I have lived in this house, this hunting cabin on concrete blocks she stuffed with insulation, since before I was born. There's a creek below, a field out front, a gravel road that runs straight for a while, and this porch. This porch. What is it about houses? The way their simplest elements contain who we are, say things for us. I was born on the living room couch, a mattress over a couple of crates. There was blood and my mom's great-aunt Sugar with bundles of herbs and warm, thick hands.

"I think we could make good money raising dogs," my mom says, nodding her head, as if I've agreed. "Half-wolf breeds. Half wild. Big buckeroos. Big stinkin' buckeroos. Don'tcha think, Angel-o?"

She doesn't wait for me to answer.

"Wolves," she says, balancing her wide, bony foot in the air, touching the moon with its silhouette, laughing. "There were goddamn wolves in Alaska."

She's getting drunk, I can tell. I close my eyes and she disappears. I don't want to be a pioneer. I am silently naming the places I might go: Chicago. New Orleans. Amarillo.

We're waiting for the storm, which we can smell coming through the trees. We're waiting for Robbie, her boyfriend with the bad teeth. We are, in some regards, waiting for dawn, or tomorrow, or next year. Leaves shuffle. Milky clouds stream past. The creek calls the water in the clouds home. My mom says it smells like desire and tips her head back, sniffing.

Desire. For a moment I know we both feel it: our shared loneliness. A deer steps into the far edge of the field — stick legs, dark pools of eyes — then turns away into the gray trees.