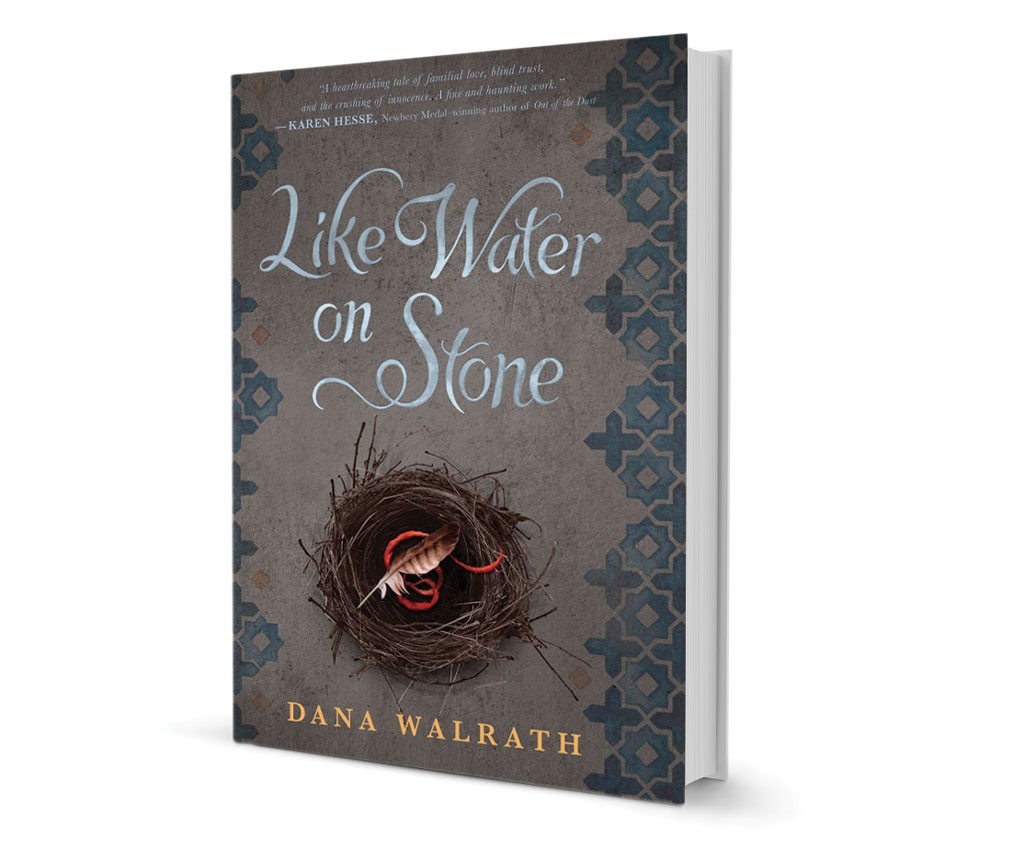

Like Water on Stone by Dana Walrath, Delacorte Press, 368 pages. $16.99.

Published November 19, 2014 at 10:00 a.m.

When author Dana Walrath was a young girl, she asked her mother about her grandmother's childhood in Armenia. The answer had a stark horror to it: "After her parents were killed, she hid during the day and ran at night with Uncle Benny and Aunt Alice from their home in Palu to the orphanage in Aleppo."

Those words "haunted" her, the Underhill author recalls in a note attached to her new young-adult novel in verse, Like Water on Stone. When Walrath was growing up, she adds, her family "didn't speak about the genocide" of Armenians by the Ottoman Empire in 1915, in which about a million and a half people died.

That silence is nothing unusual. In his 2012 novel about the Armenian genocide, The Sandcastle Girls, Lincoln author Chris Bohjalian called it "The Slaughter You Know Next to Nothing About." But with the centenary of those terrible events approaching, both these Vermont authors demonstrate that stories can and should keep memory alive.

Walrath's grandmother died before her birth, and the tale she recounts in Like Water on Stone is "entirely imagined," she writes in her author's note. It's imagined with verve, vividness and far more moments of grace and beauty than one would expect from a story about three children fleeing institutionalized mass murder. In short, what may sound like a punishing read is actually an absorbing and inspiring tale, with a verse format that makes it fleet on its feet.

Trained as an anthropologist, Walrath knows something about the power of storytelling. She holds an MFA in writing from the Vermont College of Fine Arts, has taught at the University of Vermont College of Medicine and recently delivered a TEDx talk on the therapeutic power of comics in treating dementia patients, which landed her in the pages of Entertainment Weekly. Those insights were grounded in Walrath's experience of caring for her aging mother, which she chronicled in her graphic memoir Aliceheimer's.

There are no pictures in Like Water on Stone. But it also demonstrates the healing force of narrative. As anthropologists know, children — and adults, for that matter — will confront all manner of horrors when they're presented in a setting that offers a touch of otherworldly magic and the promise of a happy ending. So it is that Like Water on Stone opens like a folktale, with these words spoken by an ardziv (eagle):

Three young ones,

one black pot,

a single quill,

and a tuft of red wool

are enough to start

a new life

in a new land.

I know this is true

because I saw it.

The "three young ones" are 13-year-old twins Shahen and Sosi Donabedian and their 5-year-old sister, Mariam. Their harrowing journey from mountainous Palu to the Syrian desert — and thence to America — follows that of Walrath's grandmother and her siblings.

The versifying eagle, who becomes the children's protector, is the novel's only supernatural element and its closest thing to a neutral narrator. His voice alternates with present-tense narration by each of the three children (sometimes in dialogue with other characters), a structure both dramatic and musical. It's easy to imagine a high school putting the book onstage, in John Brown's Body fashion.

Roughly half the novel takes place in the build-up to the massacres, giving Walrath time to establish both the historical and cultural context and each speaker's distinctive style and motivation. While Sosi feels strong ties to her family's ancestral mill and vineyard — and hopes to marry the boy next door — Shahen dreams of emigration, poring over letters from his uncle in America. He's also the first in the family to heed the coming danger, warning his father that "pogroms / will come again."

But even as their neighbors flee Armenia, the Donabedians stay put. Accustomed to living in a multicultural setting, Papa harbors a tragic faith that reason and humanity will nip ethnic persecution in the bud. "There is no them, / only single souls," he tells his family, when his wife wonders if they can trust the Turks to be reasonable. And the Muslims he knows personally, like his Turkish musician friend and his Kurdish son-in-law, "would never harm us. / This is our home."

It's an enlightened attitude for which the father will pay with his life and others', leaving his son angry and unforgiving as he leads his sisters from their burning village into the mountains. Walrath handles that clash of attitudes with great sensitivity, using Papa's beloved music — which embodies his dream of diverse elements working in harmony — as a way to reconcile Shahen to his memory.

Music also links the family to the eagle and his world: Sosi has retrieved the bird's fallen quill for her father to use to pluck his oud. The feather becomes one of three talismans the children carry with them on their grueling, 63-day journey to relative safety in Aleppo.

Free verse proves a surprisingly apt format for the story. While long-form verse narratives are almost unknown in today's adult literature, they've carved out a place in children's fiction as a way to lure in reluctant readers (all that white space!). Verse is particularly apropos here, because, as Walrath argues in her author's note, "Everyday language cannot express the scale and horror of genocide." Confronted with the full, hideous tableaux, "we all turn away," able to absorb them only "in fragments."

Those "fragments" are the building blocks of a story in which the unsaid can be as powerful as the said. Walrath uses Mariam's terse child's voice as a counterpoint to her siblings' more articulate perspectives. Her sections are more concrete and less lyrical than theirs, but often more devastating. Take her description of preparing to cross the Euphrates, which is piled high with reeking corpses:

Down to the river,

to summer.

This summer smells bad.

Rocks scrape my legs.

I hope Mama's there.

Walrath has already spelled out the ugly details of the children's mother's death for the teen or adult reader (the book carries a "14-plus" label), yet she persuasively conveys the innocence that refuses to accept such realities. Together with the eagle's overarching perspective — his power of flight gives him a wider lens — the disparate pieces come together in a picture of rare force. We learn here not only of the Armenian lives lost in 1915, but also of a way of life nearly destroyed. Walrath lovingly describes life in Palu: ripening apricots, beetles crushed to make carpet dye, celebrations with "the black pot filled with green-pepper dolma."

That pot, still filled with food crafted by their mother, is one of the three objects the children carry on their seemingly impossible journey. Their pilgrimage combines the brutality of fact, the sophistication of adult literature and the strangeness of a fairy tale, sucking in readers who might generally avoid "issue" books. Finding silent music in her stark story, Walrath contributes with her own eloquence to keeping the past alive — as both elegy and warning to the present.

Extended Excerpt From Like Water on Stone

Ardziv

As olives turned

from green to black

and warbler's second brood

hatched and fledged, I watched.

Shahen showed Mariam

new words for her stick.

Each day she scratched

long lines of letters

into the earth,

leading like paths

in rings around the mill.

She wrote his name.

Shahen.

Wave and smile to the side.

Smile, smile, half smile.

Stick, small snake.

Swan down, half smile, stick.

Smile, swan down, smile.

Shahen.

In distant lands

lines of soldiers

moved locust-like

across the earth,

their bodies clad

in identical

greens and browns,

rifles up like antennae.

The original print version of this article was headlined "Speaking the Unspeakable"

More By This Author

Speaking of...

-

Q&A: Catching Up With the Champlain Valley Quilt Guild

Apr 10, 2024 -

Video: The Champlain Valley Quilt Guild Prepares for Its Biennial Quilt Show

Apr 4, 2024 -

Q&A: Digging Into the Remnants of the Ravine That Divided Burlington

Mar 27, 2024 -

Video: Digging Into the Ravine That Divided Burlington in the 1800s

Mar 21, 2024 -

Book Review: 'The Princess of Las Vegas,' Chris Bohjalian

Mar 20, 2024 - More »

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.