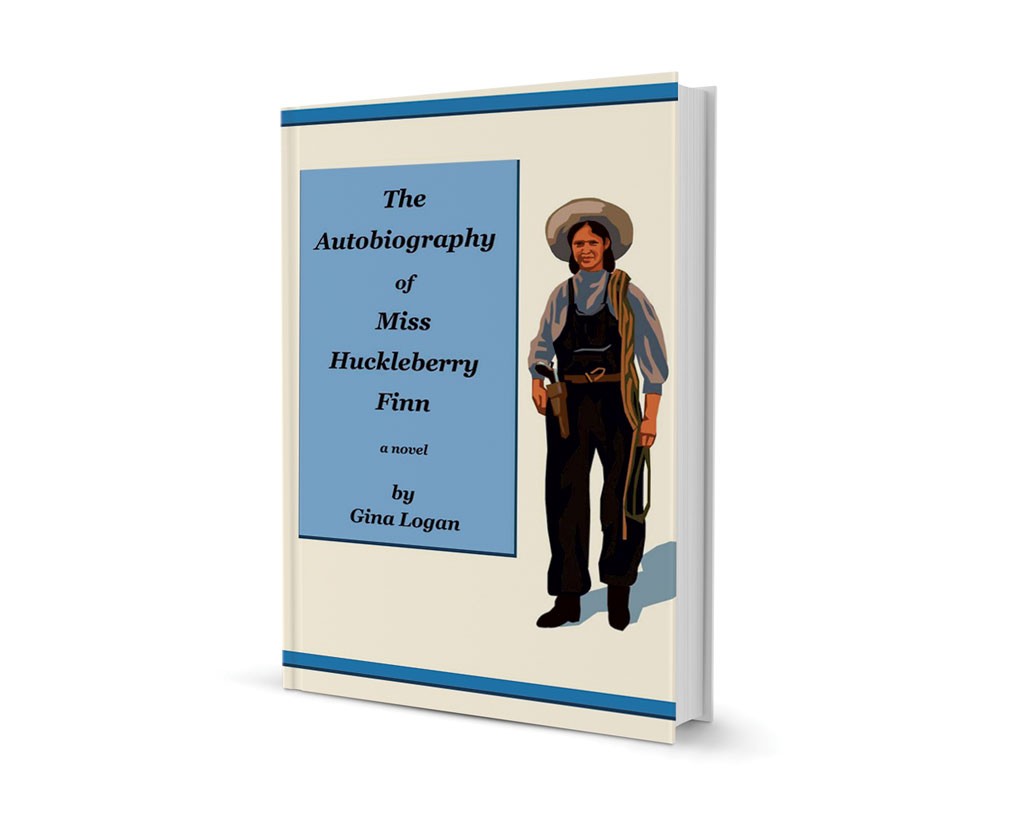

The Autobiography of Miss Huckleberry Finn by Gina Logan, CreateSpace, 404 pages. $12.99.

Published November 5, 2014 at 10:00 a.m.

I don't think many of us read The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn for fun. Most likely we were made to read it in high school. Or maybe CliffsNotes did the reading for us. As for those of us who found ourselves enjoying that trip down the Mississippi on a raft with two escapees — a young boy leaving behind his violent Pap and a slave chasing freedom — well, many of us turned out to be English majors.

And then we taught that book 20 times more and cringed when students revolted from reading the N-word 10 times on each page. "The book is a time machine," you tell your class. But unless you can get students into that machine with you and set the dial for 1840, the language remains a shocker. Compared with the irony of The Catcher in the Rye, Twain's tale itself may seem to today's teenagers like pure fantasy, a kid's story.

Yet for all the factors working against it, Huckleberry Finn holds its own in American culture. In Vermont alone, we've seen two novelists publish "spin-offs" that approach Twain's novel from daring new perspectives. First there was Jon Clinch's acclaimed 2007 novel Finn (which tells the violent story of Huck's Pap). Now comes Gina Logan's self-published novel The Autobiography of Miss Huckleberry Finn.

The novel's hook is right there in the title. We pick up a book like this because we want to see how Logan will handle the challenge she's set herself: How can Huck Finn have been a girl? In justifying the premise, will she try to out-Huck the original huckster? Will this be an exercise in mimicry? When and if Huck grows out of his/her juvenility, will we still love him/her?

The first thing Logan does is place us in that time machine. She begins her novel with a document discovered in a fire that generates the following news article:

Dowager Philanthropist's Remains Found in Earthquake Wreckage

(San Francisco, April 21, 1906) The Body of Mrs. Theophilus V. Osterhouse was recovered from the smoldering remains of her Nob Hill home by soldiers searching for survivors of the earthquake and subsequent fires that continue to devastate the city.

The document specifies that it is not to be opened and read until the year 2007. It's a 400-page autobiography written by Mrs. Osterhouse, aka Sarah Mary Williams. That's the name Twain's Huck gave himself when he dressed up as a girl — except that, in Logan's version, Huck was actually a girl dressed as a boy pretending to be a girl. Yes, gentle reader, Huck Finn was a real person — and female.

In Logan's metafiction, Twain knows Huck is a girl, interviews her and pays her $5,000 for her story. We learn that her mother named her Huckleberry because her eyes were dark like the berry. She dresses as a boy because her early life in Hannibal is rough-and-tumble, as is her trip down the river. For much of her life after that, especially when establishing herself out west, she prefers the more practical garb of menfolk. As to how much of Twain's story is true, Huck says, "he lied as much as I did, albeit he did it rather better than I ever managed to do."

Both Logan's and Clinch's novels take us back into the seminal text, as they must to legitimize their hybrid pedigrees, while making changes to increase the fun. If you've read Clinch's Finn, you may think you know what fate befell Huck's mother — but Logan tells a different tale. (Turns out she was as bad as Huck's father.) This version of Huck falls in love with a girl at her eastern boarding school, is betrayed, heads west to find her mother's relations, is betrayed again, falls in love with a black man whose father accompanied her down the Mississippi — and that's just the beginning of her adventures. Oh, and the real Huck Finn, according to Logan, did not use the N-word. That was a Twain device.

You don't have to know Twain's book to enjoy Logan's version, but it helps. The book's unlikely events are easier to accept because we trust the narrator. Huck often sounds like the Huck we know in her autobiography: "The light was all goldenish an' shinin' on the ground and the leaves an' all, and there was a little soft wind up high in the trees — no clouds to speak of, and I stopped to rest a minute..."

Logan uses this convincingly Twain-esque language to relay Huck's early memories, but in occasional instances of adult narration, she deploys a vocabulary that comes right out of a textbook of literary analysis. For instance, Huck muses, "I am still the unredeemable son of the town drunkard in those scenes, a foil to Tom and to Joe Thatcher and Ben Harper..." and "I will continue to call him [Samuel Clemens] by his nom de plume [Mark Twain]" (italics mine).

While this sophisticated literary vocabulary is a distraction, Logan generally abstains from it. Instead, she gives Huck a realistic awareness of her lack of cultivation, which becomes palpable later in the text as she matures and begins to correct her own grammar.

This is a self-published work of high quality, but the book could have used an editor to reduce the plot-dragging description. A section on how to dress as a woman shows good scholarship but could have stayed mostly in the research notes. A lengthy wagon trip across the plains feels just that — lengthy.

The novel is at its most original and intriguing in a section set in San Francisco, where the adult Huck has to deal with her mother and aunt — who run a whorehouse — and her evil cousin and uncle. It's edgy and more adult in its entertainment than anything Twain might have written. In fact, I would have liked the book better had it stayed in Frisco and kept its main character busy outwitting the denizens of that atmospheric town. The result might have been another Huck novel that channels Cormac McCarthy, as the New York Times says of Finn.

Instead, Huck has to push off for the territories once again, and Logan's plot tangles and resolutions suggest she's channeling a literary giant of another era — Dickens. Still, Twain and Dickens in one book isn't bad for the price.

Part of the novel's fun is watching Logan solve potential plot conundrums occasioned by her premise: For instance, how could Jim, the runaway slave, have traveled all those miles down the Mississippi without knowing his raft mate was a girl? (Fact is, we're told, he did know.) Watch for revelations about those two rascals who pulled the grift on the Wilks family, as well. There are enough surprises in this book to keep it fun. Just skip over the parts that drag — it won't be long before you're having fun again.

The original print version of this article was headlined "He Was a She"

Remaking Huck Finn

An adjunct English professor at Norwich University who holds an MFA from the Vermont College of Fine Arts, Gina Logan knows her Twain scholarship — and, with The Autobiography of Miss Huckleberry Finn, she's put it to inventive use. The story features a few Twain "in-jokes," she says in an email interview — for instance, about the author's "desire for wealth, his stunning lack of business success at anything but writing."

Logan self-published The Autobiography last winter and has multiple writing projects in the works, including a "mystery series, set in Vermont just after the Second World War, featuring a young doctor who finds himself embroiled in murder cases," she writes. We asked her how this unique novel came to be.

SEVEN DAYS: How did you decide to write the book?

GINA LOGAN: I have loved Mark Twain's Adventures of Huckleberry Finn since I first read it (I was around 9). Over the years, rereading the novel, I felt that Twain's narrative was ... missing something — where was Huck's mother? Why wasn't she even mentioned? What happened to her?

Twain's book also indicated quite broadly that Huck was of no consequence to the townspeople (except as a negative model for boyish behavior) until he and Tom found the gold in the cave. Then, because Huck was suddenly a person of wealth, his condition became a social concern for Hannibal. This struck me with some force.

I decided that Huck was not just the picaresque vagabond whose adventures on the raft have become part of the American myth but a much darker kind of character, at least potentially, and the novel was not just a boy's book but also a rather cynical piece of social criticism masquerading as a piece of juvenile fiction. I began to wonder if Twain had told all he knew. That led me to wondering further if a character like Huck might have a feminine analogue and, if so, what would her life be like? Then I began to speculate: What if Huck had been, actually, a girl? What if his story was actually hers? And then I thought: What a lot of fun that would be, to write Huck's true story. So I did.

SD: Why did you decide to self-publish?

GL: Because I am too old (and too conscious of the passing of time) to wait around for a publisher to notice my work favorably. (I did send queries out, but the response was pretty much "What an interesting idea. Don't think I can sell it.") The stigma of self-publishing still exists, but it is lessening, and anyway I wanted people to be able to read the book and enjoy it, now. I had fun writing it!

Speaking of...

-

Book Review: 'The Princess of Las Vegas,' Chris Bohjalian

Mar 20, 2024 -

Book Review: 'The General and Julia' by Jon Clinch

Feb 21, 2024 -

The Distant Snowy Mountain: a Short Story

Dec 20, 2023 -

Book Review: 'A Million Views,' Aaron Starmer

Nov 16, 2022 -

Book Review: 'The Storyteller’s Death,' Ann Dávila Cardinal

Oct 5, 2022 - More »

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.