Published October 1, 2014 at 10:00 a.m.

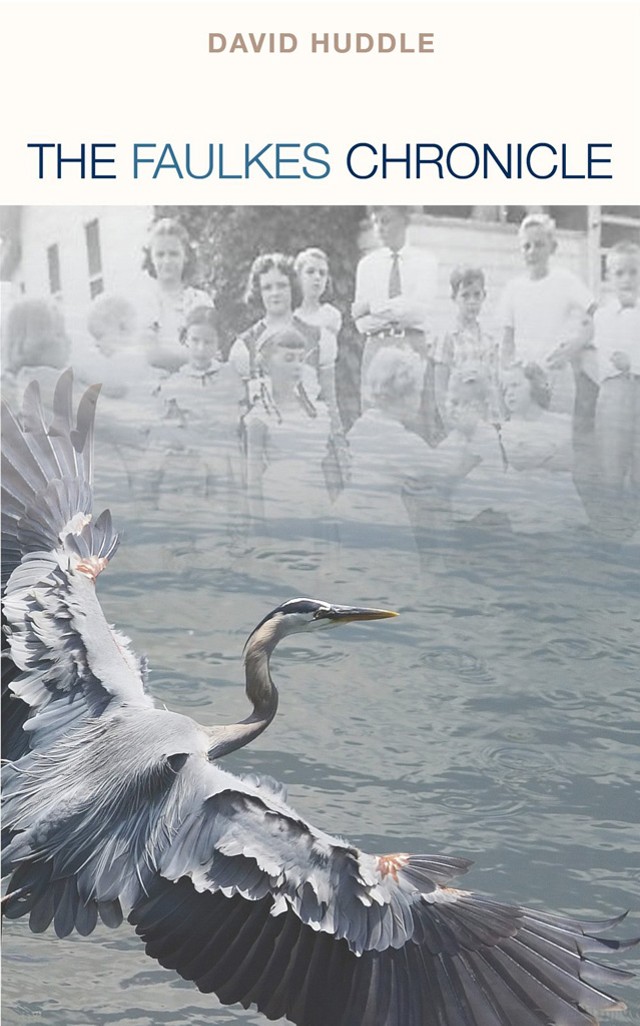

Milan Kundera once wrote, "The novel is a meditation on existence as seen through the medium of imaginary characters." Burlington writer David Huddle's new novel, The Faulkes Chronicle, is an extreme example of this assertion. It is the tale of a dying mother, told by her innumerable children just learning to live. As such, it meditates on individual existence at its end, as well as on the ever-shifting nature of collective existence, familial bonds and interdependence.

Told in the rare first-person plural, The Faulkes Chronicle is essentially a protracted, collective eulogy. Most people who deliver eulogies tend to place the lost one on a pedestal — to make him or her something other. The Faulkes children do not deviate from this custom, but they begin a bit differently from most eulogists. "In her last year of life," the novel opens, "our mother betrayed us by becoming pretty."

As the children grapple with the encroaching shadow of their mother's death, they wrestle also with the sense that she is losing her Faulkes-ness. That is, she is no longer homely, hefty and plain like the rest of them. "I hate how she's looking more and more healthy the sicker she gets," laments Angela Faulkes, speaking for them all. "She looks like a rock star who's recovering from meningitis or something." From the outset of the novel, then, the dying mother is portrayed (appropriately enough) as breaking off from the pack, in stark contrast to the rest of the Faulkeses huddled together in one indivisible unit.

This is not to say that the mother, Karen, in her beautifying betrayal, misses out on the luxuries of otherness customarily granted to the dying. Her children refer to her as "Her Majesty," and in her weakness, they get her a "Traveling Throne" that they carry (four at a time) wherever she wants to go. Later on, the family embarks on a "Farewell Tour" to places Karen wants to see once more before she dies. The bus is a double-decker, and her passenger-side chair can rise through the ceiling (into the upper level) at her command.

OK, stop.

Yes, all of this happens in the novel. The Faulkeses literally go on a "Farewell Tour," and, yes, they call it that. They really do get in a big fancy bus and drive Karen to the ocean one last time. (The ocean!) And that's not all: There are ceiling windows on the upper level of the bus so they can lean back and look at the sky. You know, like heaven.

It is almost unbelievable that a practiced, established writer like Huddle would do something so schmaltzy and hackneyed: engage questions of mortality and family by writing about a dying woman's road trip with her kids. In almost any other writer's hands, this would be a trite, two-dimensionally symbolic dive into questions so old they have all but lost their potential as artistic fodder. But Huddle plays it so straight and simple that, if you just let it happen, it works. No, really, it does.

Perhaps Huddle made it work because he just went for it unwittingly, as the novel's astonishingly unself-conscious tone sometimes suggests. But the book also shows evidence of careful craft. Huddle spends a good deal of time building rapport with the reader with comical anecdotes and moments of unexpected tenderness, so that by the time you learn the Faulkes family is going on a trip to the beach, it just feels like you're invited, that's all.

It seems most likely, then, that Huddle gave himself the challenge of crafting an almost inescapably trite premise into something worthwhile. That transformation fits the novel's theme: Loss is something we all have, but the universality doesn't make it any less meaningful.

Throughout, the reader is left guessing at the exact size of the seemingly mythologically large Faulkes family. (How many children are there? Thirty? More?) One gets a grasp of a few names — C.J., Peter, Cassie — only to have more appear in the next breath: Delmer Junior, John Milton, Sarah Jean, Pruney, Tony, Jack. Although an unwieldy cast generally begets an unwieldy novel (who did what to whom when?), Huddle turns this challenge into another unlikely victory: He manages to hold the reader in place.

Maybe he does it with that first-person plural voice, which has a binding effect on the otherwise uncontainable. At first blush, the plural narrator might seem to be a trendy writer's-workshop trick — a way to make something not-so-different look utterly different. But in Huddle's hands, the trick feels inevitable, necessary.

We gain this impression partly from the confident gait of his prose, partly from our awareness early on that no single child could recount the story alone. Despite the indistinct narrator, we do come to know individuals in the story; characters are described, and quotes are still attributed (e.g., "'We are talking about metaphysical uncertainty here,' says our brother, Robert..."). And, as we come to know the children, we see that a single pair of eyes is too clouded, too partial. C.J. would be too psychoanalytic in his approach; John Milton, too dirty. Plus, having one child tell the story would be granting unfair privilege in this family that does everything as a pack.

As far as conveying information goes, the third person would have worked just fine. But as it stands, the nebulous "we" leaves the reader feeling like a temporarily welcome stranger — a non-Faulkes allowed to see the Faulkeses intimately for a while, not unlike a guest in their home. (Or, you know, in their bus.)

I will say, though, that as a guest, I was occasionally tired of hearing the Faulkeses talk about themselves. "Faulkeses are first and foremost practical" is followed by "A Faulkes virtue is that we are not inclined to use degraded words," and then, "We are Faulkeses ... Not a crybaby among us," and then, "Aren't we Faulkeses?"

I guess this is just the accurate voice of a proud family: forever advancing its own narrative, and in trying to get you to understand it, insinuating that you never truly will. Worse than offering inside joke after inside joke, the narrative offers the constant reminder that there are so many possible inside jokes and knowing glances to which you'll never be privy. If Huddle is commenting on the virtues of quirky clannishness, he is also demonstrating how irritating and exclusive such families can be.

But, as with a real family, it is hard to complain too much when the Faulkeses are otherwise so generous — anecdotally, yes, but also lyrically. Take this gem, for instance: "The worst that can happen is what's going to happen anyway." Or this one, which delicately expresses the sentiment of the entire journey: "Anyone looking at her would say, 'That's a woman on the brink of death,' but someone else would whisper, 'Yes, maybe so, but she sure is alive right now.'"

All in all, while the Faulkes family may be a bit overwhelming and self-obsessed, it emerges from the novel as a family worth chronicling. Huddle has done the unlikely job with a poet's grace.

The original print version of this article was headlined "A Worthy Chronicle"

From The Faulkes Chronicle

In her last year of life our mother betrayed us by becoming pretty. We are a homely family. For generations we've been that way. A different idea of beauty evolved among us. Faulkeses looked for plain-faced and chubby mates. Our choices weren't particularly conscious, they were just what our genes told us to do. Now and then a Faulkes boy would be attracted to a cheerleader or a Faulkes girl would get the hots for a pretty boy. Those relationships sometimes quickened, but they could not be sustained.

Our mother had the classic Faulkes features, the small wide-spaced eyes, the negative cheekbones, the too-long chin and nose, the short forehead. When she went into chemo, chemo rearranged her face, thinned her down, installed into her repertoire of facial expressions a grimace that had every appearance of a starlet's smile. Our mother's baldness made her look delicate and vulnerable. A slightly visible blue vein that throbbed along the side of her head just above her ear made our father close his eyes to the sight of it. "It looks like a clever painter's brushstroke," he said. "Notice it, and you want to touch it."

More By This Author

Speaking of...

-

Book Review: 'The Princess of Las Vegas,' Chris Bohjalian

Mar 20, 2024 -

Book Review: 'The General and Julia' by Jon Clinch

Feb 21, 2024 -

The Distant Snowy Mountain: a Short Story

Dec 20, 2023 -

Former Vermont Gubernatorial Candidate Bruce Lisman’s American Literature Collection Fetches Millions at Auction

Jun 23, 2023 -

Book Review: 'A Million Views,' Aaron Starmer

Nov 16, 2022 - More »

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.