Published August 29, 2012 at 7:20 a.m.

If there’s one thing that freaks most people out more than dying, it’s the prospect of becoming carrion. Sophocles’ Antigone faced death rather than let her brother’s body go to the scavenging beasts. Poets use gruesome imagery of worms and maggots feasting on our corpses to evoke our insignificance. Folklore — with an assist from Edgar Allan Poe — paints the raven and vulture as birds of ill omen. No wonder most of us get our deceased loved ones embalmed and interred in sealed caskets, or cremated so there’s nothing left to scavenge.

Bernd Heinrich, a biology professor emeritus at the University of Vermont, wants us to think differently about what scavengers do to corpses — animals’, plants’ and ours. To a scientist, he writes, carrion eating is “recycling” that makes possible each creature’s “resurrection into others’ lives.” And the creatures that perform this vital corpse-processing function — including us — are “nature’s undertakers,” with all the dignity that term entails.

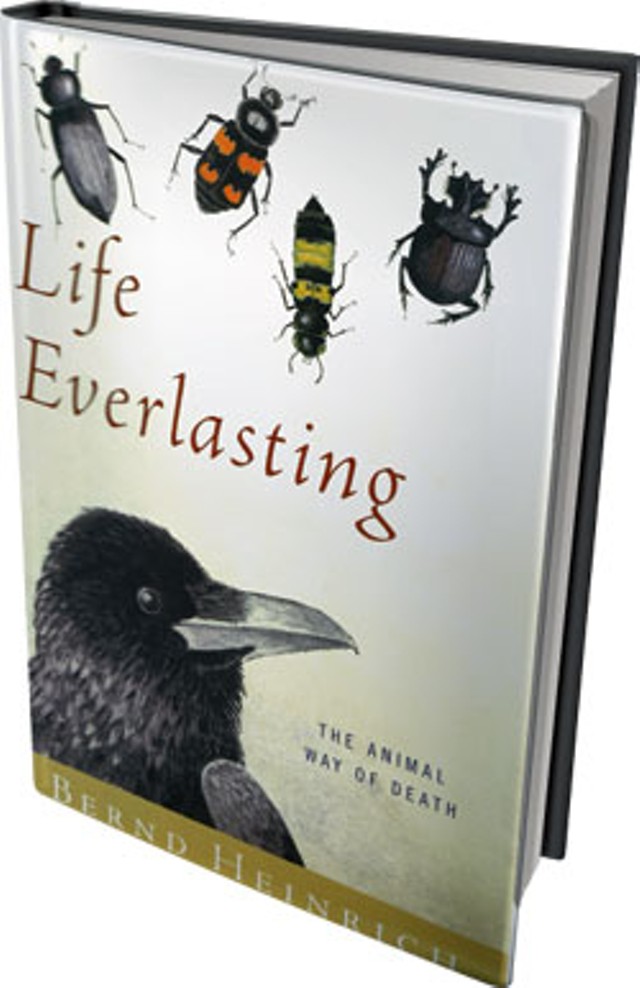

Heinrich is the author of a score of acclaimed science books for general readers, including Winter World and Summer World, colorful explorations of the northern ecosystem. He draws on a long career of outdoor observation, much of it at his cabin in the Maine woods, in Life Everlasting: The Animal Way of Death. Rather than investigating how animals die — as some readers may infer from the title — the book focuses on their postmortem disposal. Most readers, Heinrich notes, will be familiar with platitudes about the circle of life, “But the devil, as they say, is in the details.”

And what details this book offers. Each chapter is a case study in efficient corpse (or waste) recycling. We learn why sexton beetles bury dead mice and, on the other end of the scale, what happens to whale carcasses in the deep. We learn how tiny beetles recycle great quantities of elephant dung, and how early humans evolved to hunt elephants and other large mammals on our way to becoming “the ultimate scavengers of all time.”

Heinrich argues persuasively that ravens (which he has studied for decades) are not, in fact, mournful or creepy birds; and notes that vultures enjoyed sacred status in some early cultures. Turning from animal to plant decay, he demonstrates through an intricate narrative why dead trees are precious forest resources and not litter to be hauled away.

While he broaches big ecological issues, Heinrich always finds his way back to the down-and-dirty details most of us are secretly a bit curious about. A woodsman, hunter and scavenger from an early age — he discusses living off the German forest as a young World War II refugee — Heinrich takes a hands-on approach to his subject. Ever wondered what will happen if you leave a road-killed deer in your backyard? He’s done it so you don’t have to.

Reading Life Everlasting is like listening to the lectures of a brilliant professor who sprinkles his science with vivid descriptions, personal anecdotes and callouts to topical controversies. The book is sometimes disorganized, as that passionate professor’s notes might be, but rarely dry. In his chapter on ravens, for instance, Heinrich strays from his ostensible focus on “undertakers” of the northern woods to tell the story of two of his personal “raven friends,” Goliath and Whitefeather. The tale of human-animal communion is so appealing that no reader will mind the digression.

Some of Heinrich’s excursions into Big Issues are highly effective: He repeatedly, and eloquently, decries the current “human-generated wave of animal extinctions,” many of them involving “undertaker” species whose value we don’t recognize. Other argumentative passages, such as one where Heinrich questions the conventional wisdom that it’s “green” to clear out dead wood and plant new trees, could use more development to become persuasive to the layperson.

What about the philosophical issues involved in the recycling of dead flesh? In Heinrich’s view, this is a process of metamorphosis and resurrection — life returning to life — that people of all faiths should welcome, not deny.

Toward the book’s end, Heinrich takes a more radical turn, from the realm of quantifiable evidence into that of subjective experience, to make the bold argument that “we are an amalgam of past lives.” Not only do we humans recycle organic matter, as all animals do, he writes, but we recycle the beliefs, ideas and influences of those who preceded us: “We are not just the product of our genes. We are also the product of ideas.”

The book itself is the product of an idea placed in Heinrich’s mind by a severely ill friend who wrote him to inquire about the possibility of having a “green burial” at the author’s camp. In turn, Heinrich’s powerful defense of the carrion crew could contribute to mutating some readers’ ideological “DNA” on the subject of our final resting place. When you stop thinking of maggots as the lowliest of God’s creatures and start thinking of them as highly evolved recycling experts, perhaps it’s not quite as dreadful to imagine them crawling in, crawling out and playing pinochle on your snout.

"Life Everlasting: The Animal Way of Death" by Bernd Heinrich, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 236 pages. $25, hardcover. $15.95 paperback.

From Life Everlasting: The Animal Way of Death

I found the moose a day or two after it had dropped in thick forest next to a small brook. Coyote tracks surrounded it, and the coyotes had chewed through its thick hide to make a hole in the throat. A raven had already fed there, leaving white droppings on the hide. Other ravens came to feed as the coyotes enlarged the hole. Later at least a dozen turkey vultures monopolized the carcass, and then the maggots “cleaned up” after them. A couple of weeks later, a pair of ravens remained after the coyotes and vultures were done; they came daily to turn the leaves surrounding the carcass, presumably picking up maggots, fly pupae, or other insects.

When all that was left was a skeleton with dried hide covering part of it, a black bear came and dragged the remains a short way downhill. After two weeks, I found little more than a pile of hair where the animal had fallen and the vertebral column and skull some distance from that. A porcupine was eating the still-fresh bone, gnawing it off in patterns that looked like a magnification of the tooth marks mice might leave in cheese. No vultures remained despite a lingering smell. Why were the vultures no longer attracted? There was no more meat, but how would they know that without checking? Do the maggots emit a scent that repels even vultures, or are they repelled by the scent from bacterial decay?

More By This Author

Speaking of Book Review

-

Review of Sen. Patrick Leahy's New Memoir

Aug 26, 2022 -

Book Review: Pete the Cat and His Magic Sunglasses

May 27, 2016 -

Book Review: Penguin Cha-Cha

Mar 31, 2016 -

Book Review: Dog vs. Cat

Dec 16, 2015 -

Book Review: The Hummingbird by Stephen P. Kiernan

Nov 4, 2015 - More »

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.