Published July 3, 2012 at 8:06 p.m.

Boston’s Fenway Park is among the most famous and beloved sports arenas in the country. It is, as many a scribe has rhapsodized over the last 100 years, baseball’s cathedral. The oldest, and smallest, Major League park in existence, it offers a unique game experience. That is largely owing to its unusual dimensions and quirks — the Green Monster, Pesky’s Pole and the Triangle. Baseball fans of all allegiances adore it. It’s an arena rich with history and shrouded in mythology.

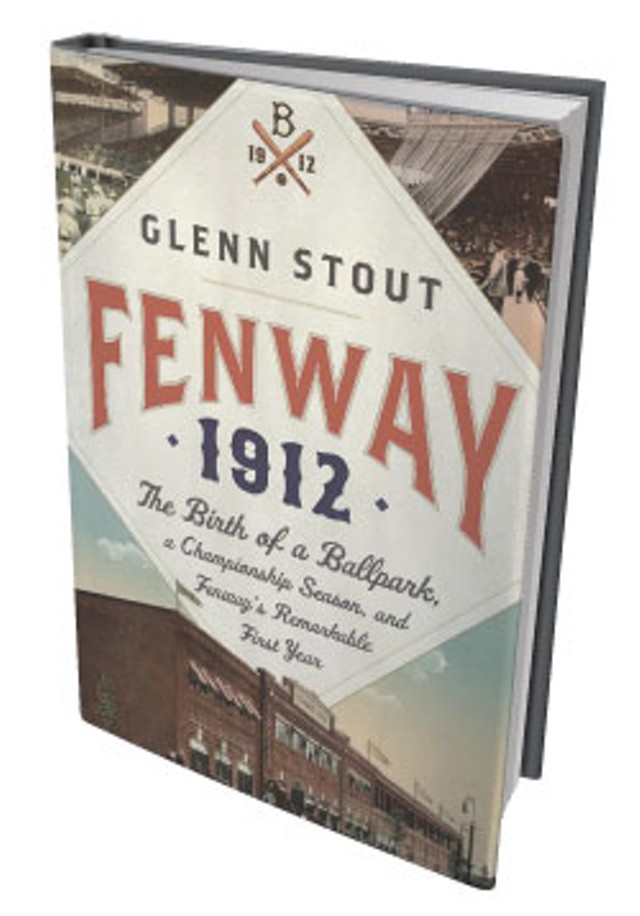

This year, Fenway Park celebrates its centennial, and, in his book Fenway 1912: The Birth of a Ballpark, a Championship Season, and Fenway’s Remarkable First Year, Alburgh-based sportswriter Glenn Stout offers an unusually comprehensive history. In that inaugural year, the team — in fourth place the previous season — became an unlikely powerhouse and World Series champion. Fenway Park was as much key to the team’s triumph as were players such as Smoky Joe Wood, Harry Hooper and Tris Speaker.

Stout is an accomplished sports writer and historian. He’s authored, coauthored, edited or ghostwritten some 80 books, including histories of the New York Yankees, the Chicago Cubs and the Red Sox. He writes a sports biography series, Good Sports, aimed at young adults. He is also the editor of the annual anthology series The Best American Sports Writing. But Fenway 1912 may be Stout’s most significant work to date. Earlier this year, the Society for American Baseball Research recognized it as the best book of baseball biography or history in 2011, granting it the prestigious Seymour Medal.

To piece together the history of Fenway Park, Stout spent three years researching the book, meticulously combing through the Boston Globe archives and microfilm of other newspapers for any tidbit he could find. But he says he specifically avoided reading other histories of the ballpark for fear of repeating inaccuracies.

“Just because something was written before doesn’t necessarily mean it was true,” Stout says in a phone conversation. Many crucial questions about the park’s origins had never been adequately answered, he adds, not even in a history he wrote in 1987 for the Red Sox Yearbook commemorating the park’s 75th anniversary. Stout says that, as he searched, he turned up even more questions and misconceptions about the park.

“We all think we know everything there is to know about Fenway,” he says. “But there is so much to the story that had never been told before.”

As an example, Stout notes that Fenway’s unique footprint has nothing to do with its present-day surroundings in Boston. Currently, the park is sandwiched between buildings on Lansdowne Street and Yawkey Way. Conventional thinking has long been that the park was designed to fit within those urban confines. But in 1912, the Fens in Boston more resembled farmland than a cramped cityscape.

“It looked like Kansas,” says Stout. He discovered that the neighborhood now surrounding Fenway was made to fit the park, not the other way around.

Before he became a writer, Stout worked as a librarian and in construction. Both experiences served him well in writing and researching Fenway 1912. He says he unearthed a lot of information about the park’s construction from plans and permits. Playing baseball in his younger days was also key to unlocking some of Fenway’s mysteries, Stout says.

His sleuthing required reading between the lines and connecting dots from various sources. Stout essentially recreated the entire 1912 season from box scores and game reports. In this way, he discovered the important role the park played in the Red Sox’s success.

“For one thing, I noticed there was an increase in outfield putouts,” he explains. The Sox’s previous home, the Huntington Avenue Grounds, was cavernous compared to Fenway. In 1908, Huntington’s center-field wall stood 635 feet from home plate, an unfathomable distance by today’s standards and a far cry from the 420-foot marker currently in Fenway’s center.

“From my experiences playing baseball, that told me that outfielders could play more shallow at Fenway,” Stout says. That suited Hall of Fame center fielder Tris Speaker, who in 1912 had one of the greatest defensive seasons ever. Because of his elite speed, Speaker could cheat in and still have time to run back when the ball was hit over his head, confident that the closer outfield wall would bail him out if he misjudged its trajectory. In 1912, Speaker first performed what would become his signature play: the unassisted double play at second base, a rarity for outfielders, also facilitated by Fenway’s smaller dimensions.

“That’s something that directly impacted the fortunes of the Red Sox that year,” Stout says.

Part of the charm of Major League Baseball’s smallest park is its intimacy. Obstructed views and odd angles aside, it allows fans to be close to the action. Ironically, the initial reviews of the park suggested the exact opposite, as fans complained of a lack of closeness both to the field of play and to other fans. Stout explains that the initial layout was much different from that of the park today. For instance, the grandstands along the first and third baselines were completely isolated from the center-field bleachers, creating a literal disconnect between fans.

The footprint of Fenway as it is now didn’t come into being until just weeks before the 1912 World Series. The Red Sox added nearly 12,000 seats to the park, including bleachers in right field and on the playing field in front of the left-field wall — any ball hit into or over the now dramatically close left-field stands was considered a ground-rule double. Another new fence was constructed in right field, but it wasn’t solid. This right-field fence was essentially a railing, and any ball that passed through it, or even under it, was a home run. It was the first time the park had been completely enclosed, becoming a structure comparable to the “bandbox” Fenway is known as today.

The Red Sox went on to best the New York Giants in the 1912 World Series, a dramatic and controversial eight-game series they won four games to three — with one game declared a tie because of darkness. That season sparked the most successful run in Red Sox history. Between 1913 and 1918, the team appeared in and won four more World Series championships. Then it sold Babe Ruth and endured an 86-year title drought before winning in 2004 and again in 2007.

But, as Stout reveals in Fenway 1912, through it all — from Ted Williams to Yaz, from Bucky “Bleeping” Dent to David Ortiz — Fenway Park has remained a dynamic testament to a game, to a team and, ultimately, to a city.

More By This Author

Speaking of Sports, health & Fitness

-

UVM Swimming and Diving Overcomes Budget Cuts to Win Conference for the First Time in Its History

Mar 13, 2024 -

Two Vermont Teens Take On the Cross-Country Junior National Championships

Mar 6, 2024 -

Youth Soccer Comes of Age in Vermont, but the Playing Field Is Hardly Level

Nov 1, 2023 -

In a Classic Vermont Mountain Road Rally, Winning Takes Precision and Smarts, Not Speed

Sep 20, 2023 -

True Grit: Gravel Biking in Vermont Is Gaining Traction and Building Community

Apr 26, 2023 - More »

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.