Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

-

Education

Scott Official Pushes Back on Former State…

-

News

Burlington Budget Deficit Balloons to $13.1 Million

-

Education

Senate Committee Votes 3-2 to Recommend Saunders…

- Court Rejects Roxbury's Request to Block School Budget Vote Education 0

- Norwich University Names New President Education 0

- Media Note: Mitch Wertlieb Named Host of 'Vermont This Week' Health Care 0

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

Getting to the Bottom of 1860 Schooner 'Sarah Ellen' in Lake Champlain

Published November 27, 2019 at 10:00 a.m.

By all historical accounts, it was a miserable day for sailing, let alone for crossing Lake Champlain in an old wooden vessel laden with stone. "The day was cold, the wind high, the spray dashing over the schooner and covering her with ice, the ropes all stiffened and unmanageable," read a December 28, 1860, article in the Burlington Free Press.

The Sarah Ellen, a 73-foot, two-masted commercial sailing vessel, departed from Willsboro, N.Y., on Wednesday morning, December 19, 1860, bound for Burlington. Filling its cargo hold were tons of quarried stone to be used in a new dock for the Vermont Central Railroad.

The vessel never reached port. Three people were aboard the schooner: Captain Henry Clay Hayward; his wife of only several months, Lucy Whitney Hayward; and a Frenchman, Joseph LaPlante. Sailing with the Sarah Ellen was a companion ship, the Daniel Webster, which was also carrying stone. It's only because of the second vessel that historians know anything about the first one's fate — unlike the scores of anonymous shipwrecks that sit on the bottom of Lake Champlain.

Precisely why the Sarah Ellen went down may never be known. But eyewitnesses aboard the Daniel Webster reported that both ships ran into a sudden, violent gale about a half mile southeast of Four Brothers Islands. It's possible that the Sarah Ellen took water over its bow or sprung a plank due to its heavy cargo. Either way, the ship quickly foundered and sank in less than 10 minutes.

The crew boarded a lifeboat, but eyewitnesses reported that it was covered with ice and immediately capsized, sending all three passengers into the frigid water, where they clung desperately to the sides. As the Daniel Webster came about and plucked LaPlante to safety, the ship bumped into the overturned lifeboat, knocking the captain and his wife into the water. The Daniel Webster came about a second time and tried to rescue them, too.

"They were seen floating on the water for nearly five minutes, Mr. Hayward supporting his wife when she sank," the Free Press reported. "[A]bout a minute after, her husband followed her to a watery grave."

The couple's bodies were never recovered. But on October 25, 2019, human hands touched the vessel that claimed their lives for the first time in nearly 160 years. On a warm and calm autumn day, scuba divers Michael MacDonald, of Salem, Mass., and Tom Howarth, of Portsmouth, R.I., made the 300-foot descent to the bottom of Lake Champlain to get a firsthand look.

Though not unprecedented in its depth, the two-hour dive demonstrated that, with ever-improving technology, more of Lake Champlain's shipwrecks are becoming accessible to researchers and recreational divers. And though this dive team abided by industry best practices by not disturbing the wreck or attaching themselves to it, maritime historians caution that such deep dives are a double-edged sword, exposing irreplaceable cultural resources to potential plunder and destruction.

The Sarah Ellen had been seen previously on video shot in 1989 by an underwater remotely operated vehicle, or ROV. Still, as one of the divers put it, nothing quite compares to seeing it in person.

"It was awesome!" MacDonald told Seven Days about his first glimpse of the Sarah Ellen. An information technology specialist at Tufts University in Boston, MacDonald, 35, also captains a dive boat based in Gloucester, Mass. "The first thing we saw going down was this mast coming out of the darkness, still standing upright and proud like it had sunk two days ago."

MacDonald spent months planning the dive with Gary Lefebvre of Colchester. Lefebvre, 61, captains the private research vessel R/V Amazon, out of Malletts Bay, from which the divers descended. He's been diving since the mid-1970s and built the 27-foot utility vessel himself, equipping it with multiple sonar units for scanning the lake's bottom. Occasionally, Lefebvre also assists local law enforcement in locating drowning victims. Mostly, though, he and his wife, Ellen, dive to objects that have yet to be identified or explored.

"It could be a tree stump. It could be a car. It could be a brand-new wreck," Lefebvre said. "But it's something that nobody else has found."

Lefebvre and MacDonald didn't discover the Sarah Ellen themselves. That honor belongs to a team led by Robert Ballard, then with the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Falmouth, Mass. Ballard is a retired U.S. Navy officer best known for his 1985 discovery of the RMS Titanic. In Vermont, partnering with researchers from the Lake Champlain Maritime Museum in 1989, he was actually searching for Benedict Arnold's missing gunboat, the Spitfire, which sank in 1776.

"We didn't find the gunboat during that survey, but we did discover the Sarah Ellen," said Arthur Cohn, now director emeritus of the maritime museum and principal investigator on the management project for the Spitfire, which was finally located in 1997.

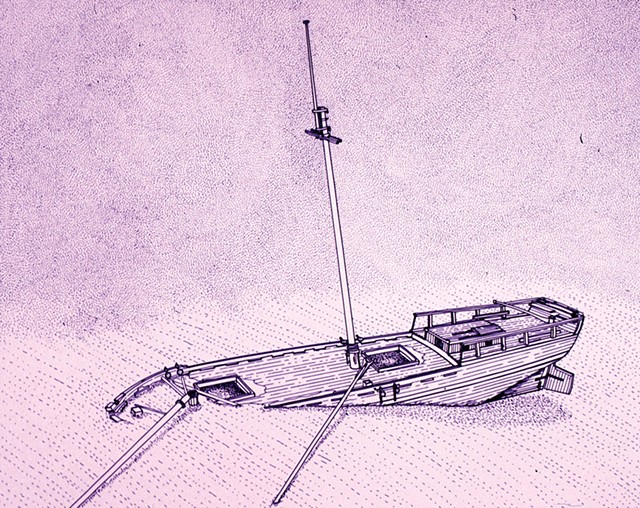

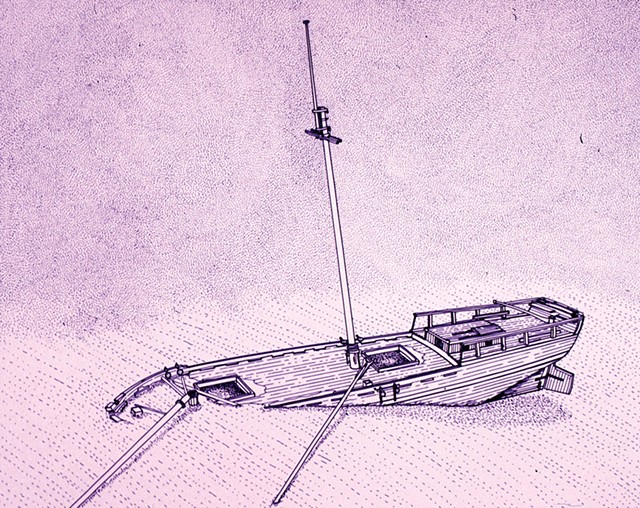

click to enlarge

- Courtesy Of Kevin Crisman

- Drawing of the Sarah Ellen at the bottom of Lake Champlain

Within days of finding the Sarah Ellen, Cohn said, researchers brought in a highly sophisticated ROV and recorded several hours of video. Despite the video's grainy quality, Cohn called it "one of the most extraordinary sites I've seen on the bottom of Lake Champlain.

"It's one of the great examples of the intact legacy that was waiting there for our generation to find," he continued. At the same time, "Finding these boats has really become the easiest part of the job. Managing the boats for their public value is more complicated."

Indeed, in 1992 the Sarah Ellen was literally minutes away from being ripped to pieces by a well-intentioned but misguided treasure hunter, who mistook the 19th-century schooner for a 20th-century aircraft. His story adds a curious wrinkle to an already colorful tale.

Harold "Webb" Maynard was a longtime firefighter with the Elmira City Fire Department, in the Southern Tier of New York. According to his 2013 obituary, Maynard, who also loved to scuba dive, "fulfilled a lifelong dream of completing a functional, two-man submarine in 1982."

In August 1992, Maynard brought his homemade submersible to Lake Champlain to search for a private jet that went missing in a snowstorm shortly after takeoff from Burlington International Airport. The January 1971 crash claimed the lives of all five people aboard. But the lake iced over within days of its disappearance and the 10-passenger, twin-engine aircraft was never found, though pieces of it washed ashore in Shelburne the following spring.

Because a wealthy Atlanta-based real estate firm owned the jet, treasure hunters assumed there were riches aboard. So when Maynard gazed through the tiny porthole of his submersible and spotted something on the lake's bottom that didn't look natural, Cohn said, he automatically assumed that its iron nails were aircraft rivets. As he put it, "It was a real case of wishful thinking."

Coincidentally, Fred Fayette, owner of Juniper Research in Burlington who's worked for years with the Lake Champlain Maritime Museum surveying the lake, happened to be on the water the same day as Maynard. Fayette, who captains the 40-foot research vessel R/V Neptune, was headed to Basin Harbor when he spotted a strange-looking utility craft anchored suspiciously close to the Sarah Ellen site. Fayette approached and asked what they were up to.

"They were very open about what they were doing," he recalled. The crew on board explained that Maynard was underwater in his submersible and had attached a series of homemade grappling hooks and ropes to what he assumed was the missing jet. Their plan was to hoist it to the surface using inflatable lift bags.

Fayette convinced the treasure hunters to halt their salvage operation until they were sure it wouldn't damage the nearby historic wreck. Fayette then alerted the maritime museum, which notified the U.S. Coast Guard and the Vermont State Police.

On August 11, 1992, Cohn and Fayette brought in a highly sophisticated ROV from out of state to survey the wreck. To their horror, they saw several grappling hooks embedded in the ship, along with more than 1,000 feet of rope draped over it. Evidently, Maynard had cut his lines before aborting his salvage mission.

Because Maynard's "stealth oddball activity," as Cohn put it, was considered an honest mistake and not archaeological looting, he wasn't criminally charged for damaging the Sarah Ellen; instead, the State of Vermont billed him for the expense of the ROV survey. But, as Cohn pointed out, the incident highlighted the growing challenges of protecting the 300 or so known sunken vessels in Lake Champlain, which has one of the best-preserved shipwreck collections in the world.

Lefebvre and MacDonald took that responsibility seriously. Their dive was highly technical, dangerous, costly and time-consuming, requiring specialized equipment, two boats at the surface, an emergency safety diver and months of planning.

Because they couldn't anchor to the wreck itself, Lefebvre explained, he had to use anchorless, GPS technology to keep his vessel in a fixed position. Had the divers missed it by a mere 10 feet in limited visibility, they could have exhausted precious time and air looking for it, and might have missed it entirely. Indeed, they had to abort their previous dive attempt in September because the visibility was "like chocolate milk," MacDonald said.

"Any dive below 100 feet in Lake Champlain is like a night dive," he noted. "You basically have no ambient light in water that deep."

It took the two divers five minutes to reach the Sarah Ellen. This time, visibility was clear enough to record high-definition color video of the entire vessel, which sits with its bow buried in the mud. Clearly visible on video are the ropes that Maynard attached to the ship, which now lay tangled on its deck.

MacDonald admitted that he'd hoped to see more 19th-century artifacts aboard in addition to the block pulleys that were used in the ship's rigging. That said, the words "Isle LaMotte," which were painted across the transom, were still legible after all that time underwater. The ship also had no zebra mussels attached, which can fully encrust wrecks in shallower waters but rarely go deeper than 100 feet.

MacDonald and Howarth spent just 15 minutes on the bottom. MacDonald would have liked to stay longer but, as he explained, every two minutes at that depth adds another 20 minutes to their decompression time. As it was, their ascent to the surface took 100 minutes because the divers had to stop periodically to avoid decompression sickness, aka the bends.

In all, the dive was considered an unqualified success, and the video they took adds significantly to the Sarah Ellen's historical record, Cohn said. At the same time, he noted, deep dives like this one present a new challenge: preserving this and other underwater relics for future generations.

"People love shipwrecks. They engage your imagination and connect you with the past," Cohn added. "We now have the ability to extend our human diving depths from the old standard, which was around 100 to 130 feet, to several hundred feet ... With the deepest water [wrecks], which were always protected by their depths, how do we best manage them moving forward?"

Learn more at lcmm.org.

The original print version of this article was headlined "Deep Dive | Getting to the bottom of the 1860 schooner Sarah Ellen in Lake Champlain"

Related Stories

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

Tags: History, Lake Champlain, Sarah Ellen, shipwreck, Video

More By This Author

About The Author

Ken Picard

Bio:

Ken Picard has been a Seven Days staff writer since 2002. He has won numerous awards for his work, including the Vermont Press Association's 2005 Mavis Doyle award, a general excellence prize for reporters.

Ken Picard has been a Seven Days staff writer since 2002. He has won numerous awards for his work, including the Vermont Press Association's 2005 Mavis Doyle award, a general excellence prize for reporters.

Speaking of...

-

Totally Transfixed: A Rare Eclipse on a Bluebird Day Dazzled Crowds in Northern Vermont

Apr 10, 2024 -

Vorsteveld Farm Held in Contempt Over Runoff

Jan 10, 2024 -

Q&A: Eva Sollberger Talks to Her Mother, Sophie Quest, About Aging

Oct 25, 2023 -

Video: Eva Sollberger Talks With Her Mom, Sophie Quest, About Aging

Oct 19, 2023 -

Plattsburgh Man Banned From Ferry for 'Disrespectful' Email

Sep 29, 2023 - More »

Comments (2)

Showing 1-2 of 2

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.

- 1. A Former MMA Fighter Runs a Wildlife Rehabilitation Center in Cabot News

- 2. Legislature Advances Measures to Improve Vermont’s Response to Animal Cruelty Politics

- 3. This Manchester Center Family Is a National Show Horse Powerhouse Animals

- 4. Welch Pledges Support for Nonprofit Theaters Performing Arts

- 5. Pet Project: Introducing the Winners of the 2024 Best of the Beasts Pet Photo Contest Animals

- 6. Q&A: Downtown Montpelier Transforms Into PoemCity Every April Stuck in Vermont

- 7. A Burlington Celebration of Nature Helps Citizen Scientists Connect With — and Count — the City's Nonhuman Residents Animals

- 1. How a Vergennes Boatbuilder Is Saving an Endangered Tradition — and Got a Credit in the New 'Shōgun' Culture

- 2. Video: The Champlain Valley Quilt Guild Prepares for Its Biennial Quilt Show Stuck in Vermont

- 3. Waitsfield’s Shaina Taub Arrives on Broadway, Starring in Her Own Musical, ‘Suffs’ Theater

- 4. Video: 'Stuck in Vermont' During the Eclipse Stuck in Vermont

- 5. Pet Project: Introducing the Winners of the 2024 Best of the Beasts Pet Photo Contest Animals

- 6. This Manchester Center Family Is a National Show Horse Powerhouse Animals

- 7. Crossing Paths: An Eclipse Crossword 2024 Solar Eclipse