Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

-

Education

Scott Official Pushes Back on Former State…

-

News

Burlington Budget Deficit Balloons to $13.1 Million

-

Education

Senate Committee Votes 3-2 to Recommend Saunders…

- Court Rejects Roxbury's Request to Block School Budget Vote Education 0

- Norwich University Names New President Education 0

- Media Note: Mitch Wertlieb Named Host of 'Vermont This Week' Health Care 0

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

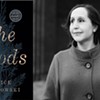

Poet and Translator Robin Myers Receives NEA Grant

Published February 1, 2023 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated March 7, 2023 at 4:40 p.m.

Some of us binged television during the pandemic; others took up bread baking. If you were Robin Myers, however, you translated 25 books from authors in five nations on two continents and found time to publish dozens of your own essays and poems.

All that work is bearing fruit. In January, the National Endowment for the Arts awarded Myers — who was born in New York, is based in Mexico City and legally resides in Washington, Vt., where her parents live — a $10,000 Literature Fellowship in Translation to continue her work with Argentinean poet Daniel Lipara. In 2022, Myers, 35, was long-listed for the National Translation Award — twice — and her own work was featured in that year's The Best American Poetry anthology. An alum of the Vermont Studio Center, she's the author of three books of poetry, most recently Tener / Having (2019), a bilingual collection that was published in Mexico, Spain, Argentina and Chile.

Myers' career path, and even her geographic path, defy easy categorizing. Spanish isn't her native language, but she does have family roots in Mexico, where her grandmother is from; for reasons both professional and personal, she has spent much of her adult life in motion.

For more than a year, Myers lived in occupied Palestine, an experience she details in a fascinating recent essay called "Hosts and Guests" for the magazine Words Without Borders. She writes: "I moved to Palestine because I was in love with a person and to Mexico because I was in love with a place. It embarrasses me a little, reducing both decisions to so breathy a verb, but it's true — or true enough."

The instinct that Myers articulates here — a tendency to search ceaselessly for the best way to express complexity while accepting the reality of imperfection — serves the challenge of translating well. Later in the essay, Myers calls translation "an obsessive interpretive art in which the boundaries between guest and host are tenderly and strenuously unstable."

That instability can also be a delight, particularly for readers who have some familiarity with both languages. Bilingual editions allow both the guest and the host, so to speak, to sit in conversation with each other. This joy can be seen in Another Life, the book of Daniel Lipara's poetry that Myers most recently translated, which was released by Eulalia Books in 2021. In an illuminating translator's note at the end of the book, Myers describes striving "to protect the gesturality of this poem ... The diction is by turns as colloquial as speech, solemn as myth, and frank and rhythmic as prayer."

In the hands of a deft translator such as Myers, much of that labor stays invisible. She renders Lipara's lines so smoothly that the English pages often don't feel like a translation at all. It helps that Lipara doesn't construct his sentences in overly complex ways, which lends an intuitive naturalness to the English versions. In the poem "silencio," he writes, "esto es lo que habla cuando nadie habla," which even readers with limited Spanish will recognize in Myers' translation: "this is what speaks when no one speaks."

Elsewhere, it becomes more apparent how the translator faced and met the challenge of maintaining the author's mix of colloquialism and solemnity. For instance, in "la isla Lipari," Lipara rhapsodically describes an island by riffing in the style of Homer's Odyssey: "y esos árboles / de frutas deliciosas / que ofrecen un deleite extraordinario."

A literal translation of this might read, "and those trees / with delicious fruits / that offer an extraordinary delight." Instead, Myers renders it as "all those trees / laden with sumptuous fruits / that offer myriad delights," subtly torquing the language in just the right way. Her addition of a word that doesn't exist in the original, "laden," helps mirror the author's heightened diction without altering his meaning.

Does striving to remain faithful to an author's intentions seem like a no-brainer? The history of translation suggests otherwise. Consider Jalal al-Din Muhammad Rumi, the 13th-century Sufi mystic whose sensual verses are quoted everywhere from celebrities' social media posts to Coldplay albums. Coleman Barks, "translator" of The Essential Rumi, could neither read nor speak Persian and simply replaced Rumi's references to Islam with his own Western, new age-influenced yearnings, crafting the version of the poet that most Americans know today.

Translation, then, is a field with far more at stake than it might seem at first. For curious readers, Myers' essays and interviews provide a satisfyingly deep dive into that pursuit: For 24 consecutive months, from 2020 to 2022, she contributed a column called "The Guest" to the online literary magazine Palette Poetry. The column is a gift: Myers ruminates on everything from the faux pas of translation to its economic challenges, and she includes interviews with translators working not just in Spanish but in such languages as Mongolian, Hungarian and Braj Bhasha, an early form of Hindi.

In column No. 23, discussing the dearth of funding for translation and the lack of standard rates, Myers writes: "What I can say from my own experience as a translator of poetry published primarily in the U.S. is, to borrow an expression from Spanish, hay de todo en la viña del señor: there's some of everything in God's vineyard, aka, anything goes."

Given the difficulty of making a living as a translator, an award like the NEA's means a lot. Reached by email, Myers described the moment she learned about the grant as surreal — and a gift in every sense of the word. "I was in Chicago as part of a literary/arts festival called Lit & Luz [Festival]," she wrote, "frantically stencilling lines of poetry onto long strips of cloth in an empty university classroom, about to embark on a few nomadic months and a series of big changes in my personal life — and I just couldn't believe it."

If some of everything can be found in God's vineyard, sometimes it offers welcome surprises, too.

silencio

esto es lo que habla cuando nadie habla

a qué suena

el cántaro de la cabeza

un arroyo de lluvia de canto de pájaros

esa ramita de sentido al borde de mi plato en la cantina

y si me muevo

y si me acerco a la corriente

es el seseo de las flores es la piedra que cae al agua

el nombre luminoso como un claro en el bosque de ruido

o más concretamente un estadounidense

que casi en castellano dice algo

silence

this is what speaks when no one speaks

what does it sound like

the jug of the mind

a rivulet of rain of birdsong

that twig of meaning at the border of my bowl in the canteen

and if I move

and if I walk up to the current

it's the rustle of flowers the stone that breaks the surface of the water

the name as brilliant as a clearing in the woods of noise

or more concretely an American

who speaks a phrase almost in Spanish

The original print version of this article was headlined "Host of Meanings | Poet and translator with Vermont ties receives NEA grant"

Related Stories

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

Tags: Books

More By This Author

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.

- 1. Legislature Advances Measures to Improve Vermont’s Response to Animal Cruelty Politics

- 2. This Manchester Center Family Is a National Show Horse Powerhouse Animals

- 3. Welch Pledges Support for Nonprofit Theaters Performing Arts

- 4. Pet Project: Introducing the Winners of the 2024 Best of the Beasts Pet Photo Contest Animals

- 5. A Burlington Celebration of Nature Helps Citizen Scientists Connect With — and Count — the City's Nonhuman Residents Animals

- 6. Animal Communicator Amy Wild Wants a Word With Your Pet Animals

- 7. A Former MMA Fighter Runs a Wildlife Rehabilitation Center in Cabot News

- 1. How a Vergennes Boatbuilder Is Saving an Endangered Tradition — and Got a Credit in the New 'Shōgun' Culture

- 2. Video: The Champlain Valley Quilt Guild Prepares for Its Biennial Quilt Show Stuck in Vermont

- 3. Waitsfield’s Shaina Taub Arrives on Broadway, Starring in Her Own Musical, ‘Suffs’ Theater

- 4. Video: 'Stuck in Vermont' During the Eclipse Stuck in Vermont

- 5. Pet Project: Introducing the Winners of the 2024 Best of the Beasts Pet Photo Contest Animals

- 6. This Manchester Center Family Is a National Show Horse Powerhouse Animals

- 7. Crossing Paths: An Eclipse Crossword 2024 Solar Eclipse