Published November 21, 2007 at 1:20 p.m.

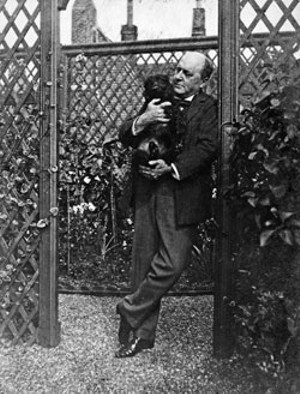

For readers of American fiction, the expatriate novelist Henry James is sort of like the Boston Red Sox: You’re either a diehard fan or a firm dissenter. Some of James’ thick domestic fiction might seem pretentious and old-fashioned — remember 10th-grade English? But more than a few literary buffs consider him one of the greatest writers ever.

Literary stylists have trouble staying current, especially when they’re dead. James, though, is still a force in contemporary culture. His novels have been made into award-winning plays and movies; he is frequently referenced in magazines and widely revered by contemporary fiction writers in the United States, the U.K. and beyond.

Since his death in 1916, James has spawned reams of lit crit. This week, the tradition continues when a new biography entitled Henry James: The Mature Master hits the shelves. The second installment of a two-volume tome on the author, the book was written by Sheldon Novick, a Norwich native and longtime professor at Vermont Law School in South Royalton.

In Mature Master, Novick quotes from stacks of archival correspondence, some of it recently released. The result is a lively read that takes a page from James’ own playbook. Just as the latter’s late novels operate from directly within the minds of their narrators, Novick’s bio is based largely on James’ own observations of daily life, as documented in letters to friends, family members and lovers.

Like its predecessor, Henry James: The Young Master (Random House, 1996), Mature Master celebrates James’ accomplishments without shying away from his darker side. Through a 500-page narrative that trails the writer’s jaunts among London, Paris, Rome and Boston, Novick highlights transformations in James’ style against the background of a shifting cultural milieu. All the while, he carefully depicts the recurring spells of depression, creative anxiety and heartbreak that accompanied James’ public success.

Biography can be a dusty, erudite enterprise. But it has its hotbeds of controversy, and Novick is right at the center of one. The Vermont author claims his work corrects errors in that of two other prominent James biographers — who vehemently disagree with his assessment. Those two scribes, Leon Edel and Fred Kaplan, have the support of University of Vermont President Dan Fogel, a lifelong James junkie who founded the Henry James Review and the Henry James Society in the late 1970s. Though he respects Novick’s “empathy” for James, Fogel calls Novick’s treatment of his subject’s sexuality “questionable.”

What’s all the fuss about? And why do flowery prose and 19th-century sexual mores still matter in a land of Dan Browns and Paris Hiltons?

************

On a recent Tuesday evening, Novick welcomes a reporter into his modest Norwich home. The man’s shingled digs rest on a sloping country lane a few hundred yards from a horse farm. Novick, 66, is slender, loquacious and grandfatherly. Like James, who lived mainly in Europe, he has tastes that hark back to the Old World. The red walls of Novick’s living room, for instance, are covered in 19th-century pastoral landscapes; his shelves sag with books on Impressionism. The whole scene recalls a London drawing room, minus the Londoners and snuff.

These accoutrements reflect not a vague nostalgia for the past but a lifelong passion. A legal historian, Novick is particularly fond of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. His first biography, Honorable Justice (Little, Brown & Co., 1989), documented the life of Henry James’ friend and contemporary, Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes.

“I’m interested in that historical moment, and in the development of ideas that you could see happening between the Holmes and James families,” he explains, sipping a cup of chamomile tea over the melody of a Bach cello sonata. Novick suggests that James’ writings, which span the Victorian and Modernist periods, offer snapshots into “the origin of the modern world.”

Producing a doorstop-sized biography of James took some time — like, almost 20 years. For one, James’ half-century of literary output dwarfs contemporary standards of “prolific” — he cranked out more than two dozen novels and a steady stream of stories, reviews, plays and travel essays. In addition, the man maintained a busy, transcontinental social life sans cellphone. That means he left behind mountains of letters and journal entries.

“I confess I thought it was going to be easy,” Novick notes of his project with a laugh. Previously, he recalls, “I had done a lot of work on the [historical] background and on Holmes. I thought, ‘Oh, Henry James, I’ll just fill that in.’ But it took quite a while.”

While Young Master spans a little-documented period — the author’s childhood — Novick’s latest work finds James at the peak of his career and the center of an international literary scene. Hence, Mature Master required tons of research in such places as the New York Public Library and Harvard University, which houses the largest archive of James family correspondence in the country.

Like a good biographer, Novick also traveled to libraries and important locations in Russia, France, Italy and the U.K., where he literally trod the terrain of James’ prose. “I had tea at Hardwicke, which is the country house where James’ novel The Portrait of a Lady opens,” Novick recalls, nibbling a piece of cheddar cheese. “The current owner was proud that her house was a landmark of literature.”

That may sound like a pleasant — almost a Jamesian — way to pass the time. But for biographers, any process of documenting a life carries tricky ethical implications; it’s hard to evoke personal details without reading too much into a subject’s behavior. In the case of Henry James, that conundrum is especially pronounced. Though a cosmopolitan schmoozer, the author was highly protective of his privacy. Plus, his only autobiography deals mainly with his childhood, so any assessment of James’ adult life is bound to be speculative.

According to Novick, that’s no excuse for faulty reporting. He says James’ life — and his sexuality in particular — has been mischaracterized by generations of biographers. Early accounts, he claims, presented an image of James as a “fussy old man.” In the 1920s, Novick continues, the author — who worked in the European tradition — was marginalized by proponents of an overly macho school of American literature.

It didn’t end there, says Novick. Beginning in the 1950s, Leon Edel’s five-volume, Pulitzer Prize- and National Book Award-winning biography of James — Henry James: A Life — took an excessively “psychoanalytical” approach to the author. Two years ago, Novick adds, a historical novel about James’ life — The Master, by Colm Tóibín — reinforced the “conventional” view of James as a “neurotic figure who wasn’t aware of his own feelings.”

Henry James’ novels “are saturated with self-awareness, passion and sexuality,” Novick insists. “The late novels especially are almost dripping with sex, and the [received] notion seems to be that it was kind of ‘unconscious.’ But I stuck to the conscious James as I found him in his letters and writings, and the observations of his friends — and critics, for that matter.” Novick argues that James was an “active” and “ambitious” gay man.

That assertion is up for debate. In a section of Young Master, Novick reports that a young James “performed his first act of love” with Holmes in a “shuttered” Cambridge bedroom. After the book came out, however, fellow James biographers Edel and Kaplan sunk their teeth into that passage like a pair of English hunting dogs, describing the Vermonter’s book as an offense to James scholarship.

In 1996, just a few months before his death, Edel sounded off on Novick’s book in an article for Slate magazine called “Oh Henry! What Henry James Didn’t Do with Oliver Wendell Holmes (or Anyone Else).” Edel began by faulting Novick — a former editor of Environment magazine whose first book critiqued the nuclear-power industry — for a lack of literary training. He then suggested Novick’s book “upsets half a century of scholarship that seems to have clearly shown James was a firm bachelor,” adding that, while Novick “attempts to turn certain . . . fancies into fact . . . his data is simply too vague for him to get away with it.” In a subsequent online letter exchange with Novick, Kaplan called some of the Vermont author’s claims “preposterous.”

UVM President Dan Fogel is more diplomatic in his criticism of Young Master, but it’s clear he has issues with Novick’s conclusions. “I think [Novick’s] work takes its place in the overall architecture of biographical work on Henry James, and it’s not an inconsiderable place,” he notes, slinging a Jamesian double negative. But Fogel maintains that Novick doesn’t compare to either Edel or Kaplan, who are generally regarded as Henry James “authorities.”

Strangely enough, Fogel happens to like Novick’s first book, albeit mostly for its “imaginative” qualities. (The UVM prez, who hasn’t yet read Mature Master, suggests Novick’s Young Master helped lay the groundwork for Tóibín’s historical novel The Master — ironically, since Novick slams that very work for its allegedly distorted portrayal of James.) Still, Fogel respectfully maintains that Young Master comes up “weak” on biographical facts.

************

They may disagree on what happened — or didn’t — in Henry James’ bedroom in 1865, but Fogel and Novick concur that the author is a towering figure in American literature. Fogel points out that James influenced such authors as Philip Roth and Cynthia Ozick. Novick mentions William Faulkner, Toni Morrison, John Updike and, most recently, Sue Miller.

“Many novelists find James nourishing,” Novick suggests. “I think James continues to represent a nearly insane standard of ambition to attain the unachievable; to use print — these little black marks on a page! — to evoke the realities of life, vividly experienced and deeply felt.”

For this biographer, whose interest in James is more historical than literary, James’ writing gets at the heart of modern civilization. Contemporary readers may have a hard time stomaching the intense “morality” of the author’s fiction, Novick concedes. But James’ happy endings are noteworthy for the way in which they marry “democracy and tradition” — an important theme for Americans seeking to connect with their cultural heritage. “I think that the interest people have in the world before 1914,” Novick speculates, “is connected to the feeling that something valuable, maybe, was lost.”

Macrocosmic theories aside, Novick is humble when it comes to questions of his own authorial intent. “You know,” he says with a blissful sigh, “influences are always kind of mysterious . . . You’re affected by the people you read whom you like . . . but it’s always hard to say what the effect has been.”

How would the “master” himself react to the controversies swirling around him? Tonight, as stars emerge above this quiet country lane, it’s easy to imagine a bemused James perched in a rocking chair, smiling coyly at Novick while nodding along to Bach and sipping tea.

But he might have a pithy comment, too. Mature Master quotes from a darkly comical story James wrote around his 50th birthday — “The Middle Years” — in which a dying novelist questions the significance of his own prose. Novick suggests the character may represent James’ “alter ego.”

We work in the dark — we do what we can — we give what we have, says the writer to a younger man from his death-bed. Our doubt is our passion and our passion is our task. The rest is the madness of art.

From Henry James: The Mature Master

Through lifelong study, like the painters who delved into the mechanism of seeing, the representation of perspective and the anatomy of color, James had found a perhaps fundamental mechanism of representative art, even of civilized community. The scattered adverbs and adjectives compose themselves into a solid figure by touching the keys of response in the reader, the general forms and qualities into which our nervous system analyzes perceptions, and reflexively imagines itself into the moment. His words are like the line drawings in perspective that we see as rounded, three-dimensional objects. His medium was the solitary imagination, but his subject was his passionate understanding, "love's knowledge" in Martha Nussbaum's precise phrase, of the strong forces that draw people together, despite all jealousies and violence. James prompts us to use a sense that combines intelligence and emotion, that allows us to imagine each other's experience and to enact in imagination the bare descriptions that we read, as if they were stage directions; he is the artist of empathy.

Info:

Henry James: The Mature Master by Sheldon Novick, Random House, 616 pages. $35.

More By This Author

Speaking of...

-

Review of Sen. Patrick Leahy's New Memoir

Aug 26, 2022 -

Book Review: Pete the Cat and His Magic Sunglasses

May 27, 2016 -

Book Review: Penguin Cha-Cha

Mar 31, 2016 -

Book Review: Dog vs. Cat

Dec 16, 2015 -

Book Review: The Hummingbird by Stephen P. Kiernan

Nov 4, 2015 - More »

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.