Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

Fear on the Farm: Trump's Immigration Crackdown Threatens Vermont's Dairy Industry

Published February 15, 2017 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated July 9, 2019 at 10:58 p.m.

Two young men in blue jeans and gray sweatshirts swung through the barn door and into the whirring works of a milking parlor last Thursday afternoon. Their boss, a Vermont native and lifelong dairy farmer, greeted them in halting Spanish.

"Buenas tardes!" he shouted over the sounds of sucking, clanking and mooing.

"Mucho frío," responded one of the men, shivering from the 10-degree temperature outside.

Like many of his peers in Vermont's dairy industry, the Addison County farmer has employed Mexican laborers for a decade and a half. They milk and care for his herd and perform the unglamorous work of keeping the farm clean, often working 12 hours a day, six days a week.

"We've come to really rely on them," he said, praising his Spanish-speaking workers' "consistency, performance, great attitude and work ethic."

But the farmer, who requested anonymity to discuss his legally dubious employment practices, may not be able to rely on migrant labor much longer.

Last week, federal Immigration and Customs Enforcement officers conducted a five-day sweep centered on Los Angeles, Chicago, Atlanta, San Antonio and New York City, arresting more than 680 undocumented immigrants. Secretary of Homeland Security John Kelly called it a "routine" law enforcement exercise — targeting known criminals — and officials said it was planned before President Barack Obama left office.

But migrant advocates in Vermont and throughout the country fear the raids amounted to the opening salvo in President Donald Trump's assault on undocumented workers — an offensive that could devastate the state's dairy industry.

During his campaign for the presidency last year, Trump initially pledged to deport all 11 million people estimated to be living illegally in the U.S., though he later said he would focus on the 2 to 3 million he claimed were a threat to public safety. Days after taking office last month, Trump signed an executive order calling for the hiring of 10,000 additional immigration officers, expanding their authority to detain immigrants without criminal records and punishing cities and states that defy his orders.

Writing early Sunday on Twitter, the president took credit for last week's enforcement action.

"The crackdown on illegal criminals is merely the keeping of my campaign promise," he wrote. "Gang members, drug dealers & others are being removed!"

As word of a nationwide dragnet spread, rumors abounded in the state's agricultural community that ICE agents had raided a farm in northern Vermont last Wednesday. According to several sources, a single worker with a criminal record had been detained days earlier, but state and congressional officials said no on-farm raids had taken place.

"The delegation's staff looked into this and were told that there had been no increased or unusual detentions in Vermont in recent weeks," spokespeople for Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.), Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) and Congressman Peter Welch (D-Vt.) told Seven Days in a joint statement.

Neither ICE nor the Department of Homeland Security responded to requests for comment.

According to Dan Baker, a University of Vermont associate professor who studies the state's migrant labor force, the rumors have put dairy farmers and workers on edge.

"People are stressed and concerned," he said. "Everybody's developing contingency plans."

State Agriculture Secretary Anson Tebbetts is among them. "There's an anxiety and fear that something may happen," he said.

On a conference call Tebbetts' agency held Tuesday for the state's dairy farmers, Leahy agriculture policy adviser Tom Berry said that Trump's executive order would "seem to make probably most of the undocumented workers on Vermont farms ... targets for enforcement action."

"But," Berry added, "exactly how [ICE] is going to follow up on that, we're just watching the news like everybody else to see what's going on in other states and what might be coming our way."

The uncertain climate has prompted workers to hunker down on the farm and avoid even trips to the grocery store, according to representatives of the Vermont advocacy group Migrant Justice. Farmers and industry leaders, meanwhile, are bracing for a potential labor shortage and the possibility that Trump's trade policies could threaten the dairy export market. State officials — led by Republican Gov. Phil Scott and Democratic Attorney General T.J. Donovan — have been pushing back on the legal front, writing legislation that would shield Vermont officials from being deputized by the feds as immigration enforcement officers.

"Vermont will not be complacent, nor will Vermont be complicit in this federal overreach," Donovan said last Thursday during a press conference with Scott in the governor's Statehouse ceremonial office.

That same day in Addison County, farmer and farmhand alike tried to ignore the legal clatter and focus on milking hundreds of cows every eight hours.

After reporting for shift change and greeting his boss, one of the laborers took his place in the pit of the milk parlor and got to work — disinfecting udders and attaching milking machines. He would repeat that process, five bovines at a time, from 3 p.m. until 3 a.m. the next day, with just an hourlong break late at night.

Asked his impressions of the new president, the Mexican hand, who also declined to provide his name, bemoaned Trump's "plan to remove the workers."

"How are we going to work?" he asked in Spanish. "More than anything, we the undocumented are concerned how we're going to continue to work."

The farmer, standing nearby in a hooded Carhartt sweatshirt, said he was equally concerned about how he would keep his cows milked if he lost his Mexican workers, who comprise nearly half of his winter workforce. He estimated he could keep the farm operating "a week, two weeks max" with the rest of his employees working overtime.

"It's not a situation I would ever look forward to, not just because of the business, but personally what these guys lay out on the line every day. The struggles they go through — to harass them needlessly," he said. "If they're breaking the law, get 'em outta here. We don't need 'em any more than American criminals. But for the most part, they just want to earn some money and send it home."

The farmer is holding out hope that Trump won't follow through with his pledge to deport millions of undocumented workers.

"He's a businessman, and I know he employs some Hispanic people," he said. "So I feel like he's saying a lot, but until he goes and does something to ruin what's going on, I think it's more talk than anything else."

The farmer said he had counted on that assumption when he voted for Trump last November.

"To me, every politician makes promises to get elected — and a lot of those promises aren't followed through," he said.

Dirty Work

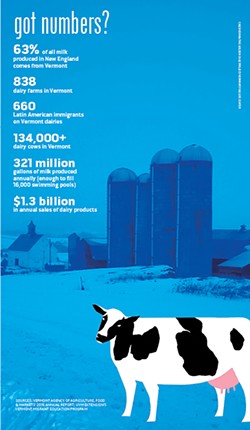

Just 1.8 percent of Vermont's population identifies as Hispanic or Latino, according to U.S. Census Bureau figures, one of the lowest rates in the country. But over the past 15 years, Latin American immigrants — primarily from southern Mexico — have come to play an essential role in Vermont's dairy industry.

"It is very hard work, sometimes at very odd hours or extended hours," said Lt. Gov. David Zuckerman, a Hinesburg vegetable and pig farmer. "Most Americans don't want to do that work anymore."

Mexican immigrants started moving north to the Green Mountains in the early 2000s, according to Erin Shea, who directs UVM Extension's Vermont Migrant Education Program. Because this sector of the economy operates largely under the radar, it's difficult to measure its size — and estimates vary wildly. But according to a recent census Shea conducted, 177 of the state's 838 dairy farms employ some 660 Latin American immigrants. While most are young, single men, close to 10 percent have children in the U.S., she said.

In a separate, less comprehensive study, Baker found that 150 of the 170 Latino dairy workers he surveyed hailed from Mexico, most from the southern states of Chiapas, Tabasco and Veracruz. Nineteen came from neighboring Guatemala.

Another 500 migrant workers, including many Jamaican apple pickers, make use of the seasonal H-2A visa to work legally on Vermont's orchards, poultry farms and slaughterhouses. But there are no guest-worker programs for year-round operations, such as dairies. So most Mexican workers, who spend years at a time on Vermont's dairy farms, are likely doing so illegally.

Like many agricultural economies, Vermont's operates largely on a "don't ask, don't tell" basis. Migrant workers typically fill out paperwork affirming their legal status and present documentation, such as a Social Security card, to their employer. But farmers are not required to ascertain the validity of the identification, nor to submit it to the federal government. So long as they pay state and federal taxes, they retain plausible deniability in the event the ID was fake or stolen.

"They all seem to have the right paperwork when they get here," the Addison County farmer said of his Mexican workers. "I don't feel like it's my job as an employer to verify that these papers are real."

The farmer says he pays his employees the minimum wage — now $10 an hour — and provides free housing, utilities and a weekly trip to the grocery store. Other workers find themselves in tougher conditions.

Pablo, a 25-year-old Tabasco native who declined to provide his last name, earned just $7.25 an hour when he first started working on an Addison County farm in 2014. His boss provided housing but no hot water.

"After finishing my shift, I would have to come back and start heating up water on the stove so I could take a bath," he said through an interpreter at Migrant Justice's Burlington headquarters.

These days, Pablo is making $10.50 an hour on a Franklin County farm and sending "a little more than half" of his pay back home to support his parents. But because he now works so close to the Canadian border, where federal agents have enhanced jurisdiction, Pablo is afraid to leave the premises more than once a month. His boss pays a woman to buy groceries for him and his fellow workers.

"It feels more dangerous there," he said of the Franklin County farm. "The immigration officers just look at you and see the color of your skin. That's enough for them to get you."

Industry officials say it's no mystery why Vermont farmers rely upon Mexican immigrants.

"There is a shortage of ready, willing and able agricultural workers. It's a crisis," said Agri-Placement Services CEO F. Brandon Mallory. "There is not a demographic in the United States that is willing to do the work. It's hard, cold and dirty."

Mallory's company, based in Rochester, N.Y., specializes in finding workers for dairy farms in 16 states. He counts close to 25 Vermont farms as clients. According to Mallory, the biggest threat to the dairies he serves is not an increase in enforcement officers or on-farm raids. Rather, he said, it's a large-scale audit of employee documentation, which would force out those without proper papers. The feds could also require farmers to use the now-voluntary E-Verify system, which enables employers to check the validity of their workers' identification.

"That's a lot easier to do and a lot more cost-effective," Mallory said. "It's a silent raid."

Like many members of his industry, Mallory hopes the federal government will one day create a visa program to accommodate dairy farms. Nearly four years ago, the U.S. Senate passed a provision long advocated by Leahy allowing guest workers to stay in the country for three years at a time.

The senator's spokesman, David Carle, explained the rationale: "The cows aren't just giving milk three months of the year."

But the comprehensive immigration reform bill died in the House and appears to stand little chance of revival during the America-first Trump administration.

Mallory thinks that's a problem.

"We either will import our workers or we will import our food," he said. "It's one or the other."

License to Discriminate?

Six years ago, Enrique Balcazar left home in Tabasco to milk cows in Vermont. He was just 17 years old.

Balcazar says he hoped to make enough money to go back to school and to help support a younger brother. He also hoped to reunite with his father, who had spent the previous eight years in the U.S. — much of that on New York and Vermont dairy farms.

The work, Balacazar found, was "grueling" and "isolating" — and the pay insufficient.

"I felt really sad and wondered if it was the right decision to come here," he said through an interpreter.

Now 23 years old, Balcazar works as an organizer and spokesman for Migrant Justice. In that role, he keeps in close touch with Mexican farmworkers around Vermont. He said his community is plagued by "uncertainty about what is happening."

"There are a lot of families who have stopped going about their day-to-day business because of the fear that they feel — have stopped going to the grocery store or stopped going to school," he said. "Families have begun making emergency plans about assigning custody to somebody else if they were to be arrested and deported."

Dave Chappelle, a labor management consultant who works closely with Vermont dairy farmers, says that migrant workers have worried about Trump since "day one" of his presidential campaign, when the New York businessman accused Mexican immigrants of "bringing drugs ... bringing crime [and being] rapists."

"That came out on Spanish language TV, and I had migrant workers asking me about it the day he said it. They were like, 'Who's this guy?'" Chappelle recalled. "The message that he's sending is that this community is not welcome here."

According to Balcazar, that sort of discrimination is hardly novel. "It's something that we as a community have always had to confront — the fact that we're treated as criminals, persecuted, insulted — just because people don't understand the causes of migration," he said. "But it became a more difficult moment than before, because now those sentiments had found their spokesperson."

In recent years, migrant activists have won hard-fought victories in Vermont, including enactment of a statewide, bias-free policing policy and the creation of noncitizen driver's licenses. Those initiatives reduced the likelihood that an undocumented worker would be pulled over and arrested simply for leaving the farm to buy groceries.

But even those changes didn't keep ICE agents from pulling over Vergennes farmworker Miguel Alcudia last September as he drove to a nearby bank with a valid driver's license. The 21-year-old Migrant Justice activist spent three weeks in detention for overstaying his visa. A public outcry helped win his release.

"Being locked up like that completely changed my life," he said through an interpreter. "But what got me through it was the hope that the community I belong to here would rally behind me."

Alcudia might not have been so lucky under the Trump administration. Last month's executive order permits ICE agents to detain and deport anyone who has "committed acts that constitute a chargeable criminal offense" — a description that applies to anyone whose papers aren't in order.

"For me, the real concern is that the bar has really been lowered," said state Rep. Peter Conlon (D-Cornwall), who used to work for Mallory at Agri-Placement. "But in the end, it takes more money from Congress to make this happen. And unless that money is there, enforcement can only go so far."

Nevertheless, Chappelle argued, "The damage to the migrant community has already been done." Some smaller farms, he said, have turned to fully automated robotic milkers. And some workers have returned home, hoping to avoid deportation so they might return legally under a future guest-worker program.

Migrant Justice organizer Brendan O'Neill, meanwhile, worries that the hostile climate toward undocumented workers will push them into exploitative working situations "with fewer rights and protections."

"Trump creating more fears and a bigger crackdown drives people into conditions they wouldn't accept under other circumstances," he said.

"We've worked really hard to, little by little, come out of the shadows," Balcazar said. "Now we have a situation where the current administration wants to have us living back in the shadows."

'This Is Our Livelihood'

click to enlarge

- caleb kenna/the golden cage project/vermont folklife center

- Inside a milking parlor on a Vermont dairy farm

The president's words have rattled dairy owners, too.

"The first time that Trump made those comments that Mexican people are a bunch of criminals and rapists, I cried," said a second Addison County dairy farmer, who also requested anonymity. "I couldn't believe someone could stand up in America in his position and make that kind of a statement and get away with it."

The farmer, who has employed Mexican workers for a decade, has come to the opposite conclusion as Trump.

"The people I know are wonderful people," she said. "They care about their jobs. We trust them with our animals, for God's sake. This is everything for us. This is our livelihood."

It's also critical to Vermont's agricultural economy. Though kale may get more attention these days, cow's milk still accounts for $504 million of the state's $776 million commodities market, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Including value-added products, such as cheese and ice cream, dairy brings in $1.3 billion in sales and spurs $2.2 billion in economic activity, according to the state Agency of Agriculture, Food & Markets.

It's not just Trump's immigration policies that might hurt Vermont's dairy industry. The president has also proposed protective tariffs that could spark a trade war.

"If we were to lose our export markets, it would have a huge, immediate impact on the food industry," the second farmer said. "Period."

According to the U.S. Dairy Export Council, a quarter of the nation's $5 billion in annual dairy exports go to Mexico. The Trump administration has floated a 20 percent levy on Mexican imports to pay for the wall he hopes to erect between the two nations — a move that could prompt countermeasures.

"There's a lot at stake," said Agri-Mark Family Dairy Farms cooperative spokesman Doug DiMento. "We all want to protect U.S. jobs. We all want to protect our borders. But at the same time, export markets are difficult to find. We want to protect those markets."

Roughly one-third of Vermont's dairy farmers belong to Agri-Mark, which owns the Cabot brand. The co-op employs 120 people at a Middlebury plant and 250 in the town of Cabot.

"For us, one of the most important things is to protect farmers who may have workers who aren't properly documented, " DiMento said.

The second farmer says she's trying not to despair over the possibility that she could lose her loyal, dependable workforce.

"I'm going to remain optimistic," she said. "Dairy farmers — we have an optimistic outlook, anyway. We're always hoping for better weather. We're always looking for a better price."

But the daughter of Canadian immigrants can't shake the feeling that there's something fundamentally unfair about targeting the very people sustaining Vermont's agricultural economy.

"They're not taking away jobs. They're filling a void," she said. "They're here for the same reasons our parents were. They're here to provide a better life for themselves and their families."

Plan B

click to enlarge

- caleb kenna/the golden cage project/vermont folklife center

- Migrant workers on a Vermont dairy farm

Two weeks ago, the Agency of Agriculture convened a meeting of dairy industry leaders at the Vermont Farm Show in Essex. The goal? To prepare for an uncertain future.

"If there was to be a [federal enforcement] action, we need to have a contingency plan, because the cows need to be milked at a minimum of twice a day, seven days a week," said Tebbetts, the state agriculture secretary. "We would need to work with a farmer to make sure that would get done."

Tebbetts cautions that any plan B remains in its early stages, but he imagines volunteer work crews, such as those that appeared in the aftermath of Tropical Storm Irene, to milk cows on a short-term basis. In the longer term, he hopes to work with the Vermont Department of Corrections to train inmates to milk. Tebbetts' agency is also exploring whether dairy farmers could use the H-2A visa program, though its 10-month limit would pose challenges for their year-round operations.

"If there was a statewide crackdown, we'd have to deal with it head-on, because there's a tremendous amount of money at stake, and the health of the cows is at stake, as well," said Tebbetts, who grew up on a Cabot dairy farm and still lives on the property.

Meanwhile, the state legislature has begun to debate a bill drafted by Scott, Donovan, and the Civil Rights and Criminal Justice Cabinet they have convened.

The legislation, introduced last Thursday by a tri-partisan group of lawmakers, prohibits state and local officials from collecting and disclosing to the federal government "personally identifying information," including race, religion, national origin and immigration status. It also bars any Vermont authority, other than the governor, from entering into immigration enforcement agreements with the feds.

That second provision is aimed at Trump's January 25 executive order, which directs the secretary of homeland security to strike accords with state and local officials to empower agencies under their control "to perform the functions of an immigration officer." Those functions include "the investigation, apprehension or detention of aliens in the United States."

"If we make it so only federal agents are the ones carrying this out, that would slow the pace of removal of workers off farms," explained Zuckerman, the lieutenant governor. "That alone would give us more time to make adjustments as needed."

Public Safety Commissioner Tom Anderson, who oversees the Vermont State Police, says state law enforcement officers remain committed to nondiscrimination policies — despite the federal crackdown.

"We're not going to do anything different with respect to what we're doing and our fair and impartial policing policies," he said. "That hasn't changed. That isn't going to change."

Vermont farmers and workers have allies in the state's congressional delegation, too. Leahy, Sanders and Welch "are paying close attention and are greatly concerned" about Trump's executive order, their spokespeople said in their joint statement.

"In particular, foreign workers on Vermont dairy farms seem to be in an especially precarious position, and there is a lot of uncertainty on all sides about what happens next," they said. "That is unacceptable."

Politicians aren't the only ones preparing for the unknown.

Leslie Holman, a Burlington attorney and past president of the American Immigration Lawyers Association, has been recruiting her peers to represent potential detainees. She has also been advising undocumented workers to designate a contact person who can coordinate legal assistance — and to keep that person's phone number handy.

"Farmers should certainly be talking to their workers to make sure that they have this information with them, so there's someone they can go to," she said.

Balcazar, the Migrant Justice spokesman and former farmworker, says his community feels lucky to have "a lot of allies" in Vermont.

"The state needs to stay strong in this political moment and stand up for itself," he said.

Alcudia, the recently detained worker, echoed the sentiment.

"You can't live under fear," he said.

Related Stories

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

More By This Author

About The Author

Paul Heintz

Bio:

Paul Heintz was part of the Seven Days news team from 2012 to 2020. He served as political editor and wrote the "Fair Game" political column before becoming a staff writer.

Paul Heintz was part of the Seven Days news team from 2012 to 2020. He served as political editor and wrote the "Fair Game" political column before becoming a staff writer.

Speaking of...

-

More Vermont Seniors Are Working, Due to Financial Need or Choice. They May Help Plug the Labor Gap.

Apr 17, 2024 -

In Vermont, the Total Solar Eclipse Will Turn Work Life Briefly Upside Down

Apr 3, 2024 -

'In This Together': A Doula and Birth Photographer Has Her Third Baby at Home

Mar 12, 2024 -

Haley Scores Win Over Trump in Vermont

Mar 5, 2024 -

Nikki Haley Plans Campaign Stop in Vermont on March 3

Feb 26, 2024 - More »

Comments (13)

Showing 1-10 of 13

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.

- 1. La Montañuela and D’Aversa Furniture to Open Wine Bar-Showroom in Vergennes Food News

- 2. Three Questions for Kate Blofson of Jericho’s Born to Swarm Apiaries Agriculture

- 3. New Sheep Shop Café on a South Woodbury Homestead Gathers the Herd Food + Drink Features

- 4. The Café HOT. in Burlington Adds Late-Night Menu Food News

- 5. After 33 Years, Cheese & Wine Traders in South Burlington Shutters Abruptly Food News

- 6. Pauline's Café Closes in South Burlington After Almost Half a Century Food News

- 7. Montréal's Jewish Eateries Serve Classics From Around the World Québec Guide

- 1. Montréal's Jewish Eateries Serve Classics From Around the World Québec Guide

- 2. Pauline's Café Closes in South Burlington After Almost Half a Century Food News

- 3. After 33 Years, Cheese & Wine Traders in South Burlington Shutters Abruptly Food News

- 4. Jacob Holzberg-Pill Helps Cultivate Vermont’s Growing Appetite for Edible Landscaping Agriculture

- 5. Small Pleasures: Monument Farms Dairy’s Chocolate Milk Inspires Devotion Small Pleasures

- 6. Ondis Serves Seasonal Fare With a Side of Community in Montpelier Food + Drink Features

- 7. New Sheep Shop Café on a South Woodbury Homestead Gathers the Herd Food + Drink Features