November 01, 2021 PAID POST » Food + Drink Features

Published November 1, 2021 at 11:40 a.m. | Updated November 17, 2021 at 7:25 p.m.

Groennfell Meadery is the kind of locally owned business Vermonters love; its name means “green mountains” in old Norse. A craft mead maker that brews a variety of alcoholic beverages made from honey, Groennfell is owned by husband-and-wife team Ricky and Kelly Klein. It started at an industrial building behind Costco in Colchester in 2013 and, six years later, moved to a bigger facility in a St. Albans industrial park.

When the pandemic hit, the company had five employees and wanted to keep them working. At that time, most of its business was in direct sales at events and bars that offered its brews on draft. That revenue instantly plummeted.

But instead of sinking alongside those sales, the Kleins sailed Viking-inspired Groennfell in a new direction: selling online to out-of-state mead mavens. Applying for licenses to sell alcohol in other states required massive amounts of paperwork, but the effort paid off.

When Groennfell started selling online, the owners were hoping to sell about 49 cases per month. In May last year, the meadery moved 50 cases in a single day, and many days like that followed. It went from filling a UPS van daily to filling a semitrailer truck every day. In its seven years in business, Groennfell had never surpassed $300,000 in annual sales; in 2020, it reached $3 million.

The company now has 20 workers and delivers mead directly to consumers in 44 states. It also works also with distributors in 12 states.

Helping to fuel that growth is the Vermont Economic Development Authority, aka VEDA, a quasi-governmental entity that helps growing Vermont businesses such as Groennfell bridge gaps in their financing.

When the Kleins wanted to put solar panels on the roof of their 23,000-square-foot building in St. Albans, they found out that their lender, Mascoma Bank, would secure only a portion of the nearly half-million-dollar price tag. Mascoma, as well as SunCommon, the Waterbury company that installed the energy system, suggested that the Kleins work with VEDA to cover the remaining amount.

VEDA agreed to loan Groennfell the $180,000 it needed. SunCommon completed the solar project last fall. In the 12 months since, the Kleins said, the array has generated enough power for the entire property — none of it from fossil fuels.

Groennfell got a second VEDA loan this year for other equipment focused on efficiency, including a faster delivery system for the hot water needed to mix with and dissolve the honey in the brewery’s tanks. The company also purchased a box-making machine to package its shipments, so its employees can focus on more significant tasks.

Thanks to VEDA, “we were able to make investments in our values, which are to have good, safe jobs for our employees, and to be able to make a positive impact in our community and for the environment that we live in,” said Kelly, the company’s CEO.

Since its inception, VEDA has made loans totaling more than $2.5 billion. It can approve up to 40 percent of the cost of a project, though that limit doesn’t apply to farmers, renewable energy projects or very small loans. VEDA doesn’t provide full financing for projects; instead, it works in partnership with other lenders to put together a complete package, filling the holes that other institutions leave and charging more reasonable rates than are typical for secondary financing.

“What we do is bridge a gap that may exist in a capital stack,” Polhemus said. “We can come in and take a lien that would be underneath the bank and lend more money so that the borrower has to come up with less equity. This gives the banks the security to say yes when they might have said no to a loan.”

Unlike a bank, VEDA holds no money from customer deposits. It fills its coffers by borrowing from other financial institutions, adding a small premium on its interest rates to cover its overhead costs.

Many Vermonters have never heard of VEDA, but most have seen the results of its work. VEDA even helped Ben & Jerry’s buy its first major ice cream-making equipment in 1979 with a $20,000 loan. A few years later, VEDA issued a $2.1 million bond to finance the acquisition of the now-famous factory in Waterbury. “You can go anywhere in the state, and you’ll see what we’ve financed — a farm or a small country store or a manufacturer or an industrial park.”

Phelan and Kelsey O’Connor bought land in South Hero in 2017 for their pig farm, Pigasus Meats. They applied to the Vermont Land Trust, which protects the state’s natural landscape, and worked with the Farm Service Agency, a division of the U.S. Department of Agriculture that loans money to farmers. The agency’s rules prevented it from lending the full amount after their down payment of less than 10 percent, Phelan said. VEDA picked up the remaining tab and offered them a locked-in interest rate.

Phelan said “having terms that allowed us to pay for the property but not have it taking all of our income every month,” helped them keep the business competitive.

They also built a relationship with VEDA, which came in handy during the pandemic. The VEDA lender who worked with the O’Connors to buy their farm called or emailed almost every week asking what they needed and offering to send them information and applications for the federal Paycheck Protection Program or other grant opportunities.

She was also able to talk with them about different VEDA programs that could help the farm expand. COVID-19 led consumers to cook more at home — and to indulge in delicacies. That spurred high demand for the farm’s pork products: sausage, bacon, chops, roast and ground meat. The farm also increased its restaurant accounts as businesses shifted to takeout and delivery orders, and it began supplying the high-end charcuterie purveyor Babette’s Feast, in Waitsfield.

Pigasus is a “feeder to finish” operation, meaning it doesn’t farrow, or breed and birth piglets. It dabbled in farrowing a few piglets last year and will consider resuming that operation, Phelan said. It started with 60 pigs in South Hero. This year, Pigasus will “finish,” meaning raise and bring to the slaughterhouse, almost 340.

The O’Connors would like to expand to 500 if they're able to find a slaughterhouse that can handle that number, Phelan said. For the long Vermont winters, Pigasus could use more hoop housing and grain-handling capacity and, eventually, a second well for water security, he noted.

Banks are generally very cautious when lending money to farmers, who face unpredictable challenges of market forces and the weather. That’s why VEDA makes farms a priority. Said Polhemus: “We got into it many, many years ago because the state saw that there was a need for more capital in the ag sector.” VEDA’s experience makes a huge difference to borrowers like Pigasus, said Phelan. “They understand that there's a seasonality to things, that extreme weather patterns happen, markets can be volatile at times.”

He added, “Having that insight and industry understanding is invaluable.”

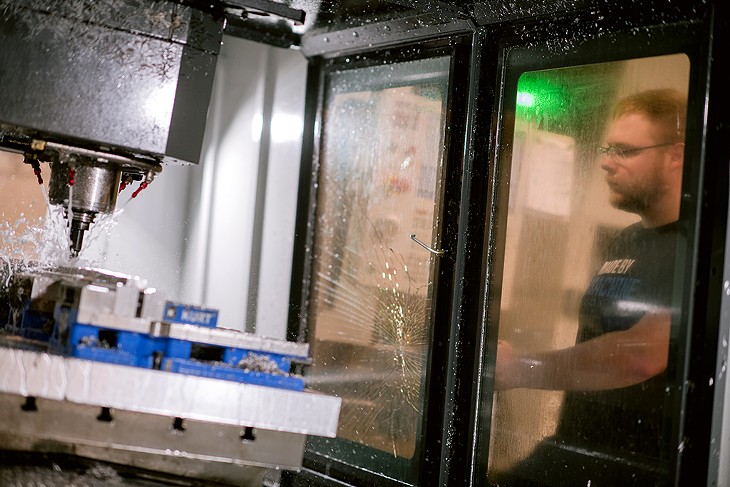

Brian Kippen and Kacie Merchand grew up in Tunbridge and met in middle school. Brian was living in California in 2011 when he founded a company there, KAD Models & Prototypes. It creates prototypes and models of products in development for clients that make everything from medical devices to wireless chargers; Kacie later joined the company as chief operating officer.

When they wanted to add a secondary manufacturing site to handle more business and build KAD’s East Coast client base, they found the perfect property: A former tractor service center in East Randolph that included three buildings and six acres. It had ample electricity, access for trucks and space for light manufacturing. And nearby, Vermont Technical College could supply advanced manufacturing students as potential employees.

They were ready to buy the property for $365,000, but there was just one problem: cleaners that were commonly used to maintain automotive and industrial equipment had leached into the concrete floor. The new owners would have to pay for remediation.

Brian and Kacie couldn’t clean up the site unless they bought it. But they couldn’t buy it without a loan, and a bank wouldn’t write one for a contaminated site. They were stuck.

The Vermont Agency of Commerce and Community Development connected them with VEDA to underwrite the cleanup costs. KAD received a grant of just over $50,000 from the state’s Brownfield Revolving Loan Fund for remediation.

Then, VEDA made the deal happen. The authority brought in Community National Bank to finance the property purchase, wrote a second loan for the purchase, and arranged for a contingency to ensure cleanup could take place before KAD closed on the sale. Another bank loaned nearly $900,000 for new equipment and expansion expenses.

VEDA coordinated the players, hosting conference calls and sending KAD to additional sources for assistance. VEDA’s involvement acted as a stamp of approval, giving other entities the assurance to work with the company, Brian said.

“They helped us navigate the whole system and were on the phone at times when it was necessary to talk to the state to continue things moving.”

Polhemus acknowledged that its lenders hold hands when necessary. “There’s so much that goes on behind the scenes to bring something to a close,” she said.

In KAD’s case, VEDA helped bring a new business to Vermont, put a vacant property to use and create five jobs. Brian and Kacie have moved back east to oversee the East Randolph operation, which he said he expects to tally $1,250,000 in revenue this year.

“Without VEDA, this location would probably have zero dollars of revenue,” he said. “So we’ve retained one and a quarter million dollars for the Vermont economy.”

That’s what it’s all about.

When the pandemic hit, the company had five employees and wanted to keep them working. At that time, most of its business was in direct sales at events and bars that offered its brews on draft. That revenue instantly plummeted.

But instead of sinking alongside those sales, the Kleins sailed Viking-inspired Groennfell in a new direction: selling online to out-of-state mead mavens. Applying for licenses to sell alcohol in other states required massive amounts of paperwork, but the effort paid off.

When Groennfell started selling online, the owners were hoping to sell about 49 cases per month. In May last year, the meadery moved 50 cases in a single day, and many days like that followed. It went from filling a UPS van daily to filling a semitrailer truck every day. In its seven years in business, Groennfell had never surpassed $300,000 in annual sales; in 2020, it reached $3 million.

The company now has 20 workers and delivers mead directly to consumers in 44 states. It also works also with distributors in 12 states.

Helping to fuel that growth is the Vermont Economic Development Authority, aka VEDA, a quasi-governmental entity that helps growing Vermont businesses such as Groennfell bridge gaps in their financing.

When the Kleins wanted to put solar panels on the roof of their 23,000-square-foot building in St. Albans, they found out that their lender, Mascoma Bank, would secure only a portion of the nearly half-million-dollar price tag. Mascoma, as well as SunCommon, the Waterbury company that installed the energy system, suggested that the Kleins work with VEDA to cover the remaining amount.

Interested in learning more about VEDA loans?

Groennfell got a second VEDA loan this year for other equipment focused on efficiency, including a faster delivery system for the hot water needed to mix with and dissolve the honey in the brewery’s tanks. The company also purchased a box-making machine to package its shipments, so its employees can focus on more significant tasks.

Thanks to VEDA, “we were able to make investments in our values, which are to have good, safe jobs for our employees, and to be able to make a positive impact in our community and for the environment that we live in,” said Kelly, the company’s CEO.

A unique lender

VEDA was created by the Vermont Legislature in 1974. Its mission? To enhance the state’s economy by bolstering businesses that create jobs and contribute to public policy goals. The authority started with a focus on industrial parks but expanded to a variety of funding programs, including those with an emphasis on the agriculture sector, said Cassie Polhemus, VEDA’s CEO.Since its inception, VEDA has made loans totaling more than $2.5 billion. It can approve up to 40 percent of the cost of a project, though that limit doesn’t apply to farmers, renewable energy projects or very small loans. VEDA doesn’t provide full financing for projects; instead, it works in partnership with other lenders to put together a complete package, filling the holes that other institutions leave and charging more reasonable rates than are typical for secondary financing.

“What we do is bridge a gap that may exist in a capital stack,” Polhemus said. “We can come in and take a lien that would be underneath the bank and lend more money so that the borrower has to come up with less equity. This gives the banks the security to say yes when they might have said no to a loan.”

Unlike a bank, VEDA holds no money from customer deposits. It fills its coffers by borrowing from other financial institutions, adding a small premium on its interest rates to cover its overhead costs.

Many Vermonters have never heard of VEDA, but most have seen the results of its work. VEDA even helped Ben & Jerry’s buy its first major ice cream-making equipment in 1979 with a $20,000 loan. A few years later, VEDA issued a $2.1 million bond to finance the acquisition of the now-famous factory in Waterbury. “You can go anywhere in the state, and you’ll see what we’ve financed — a farm or a small country store or a manufacturer or an industrial park.”

Investing in Vermont farms

Agriculture is key to Vermont’s economy and brand, and VEDA works to cultivate it, often going beyond just finding financing.Phelan and Kelsey O’Connor bought land in South Hero in 2017 for their pig farm, Pigasus Meats. They applied to the Vermont Land Trust, which protects the state’s natural landscape, and worked with the Farm Service Agency, a division of the U.S. Department of Agriculture that loans money to farmers. The agency’s rules prevented it from lending the full amount after their down payment of less than 10 percent, Phelan said. VEDA picked up the remaining tab and offered them a locked-in interest rate.

Phelan said “having terms that allowed us to pay for the property but not have it taking all of our income every month,” helped them keep the business competitive.

They also built a relationship with VEDA, which came in handy during the pandemic. The VEDA lender who worked with the O’Connors to buy their farm called or emailed almost every week asking what they needed and offering to send them information and applications for the federal Paycheck Protection Program or other grant opportunities.

She was also able to talk with them about different VEDA programs that could help the farm expand. COVID-19 led consumers to cook more at home — and to indulge in delicacies. That spurred high demand for the farm’s pork products: sausage, bacon, chops, roast and ground meat. The farm also increased its restaurant accounts as businesses shifted to takeout and delivery orders, and it began supplying the high-end charcuterie purveyor Babette’s Feast, in Waitsfield.

Pigasus is a “feeder to finish” operation, meaning it doesn’t farrow, or breed and birth piglets. It dabbled in farrowing a few piglets last year and will consider resuming that operation, Phelan said. It started with 60 pigs in South Hero. This year, Pigasus will “finish,” meaning raise and bring to the slaughterhouse, almost 340.

The O’Connors would like to expand to 500 if they're able to find a slaughterhouse that can handle that number, Phelan said. For the long Vermont winters, Pigasus could use more hoop housing and grain-handling capacity and, eventually, a second well for water security, he noted.

Banks are generally very cautious when lending money to farmers, who face unpredictable challenges of market forces and the weather. That’s why VEDA makes farms a priority. Said Polhemus: “We got into it many, many years ago because the state saw that there was a need for more capital in the ag sector.” VEDA’s experience makes a huge difference to borrowers like Pigasus, said Phelan. “They understand that there's a seasonality to things, that extreme weather patterns happen, markets can be volatile at times.”

He added, “Having that insight and industry understanding is invaluable.”

Helping to close the deal

VEDA also smooths the way for borrowers, working with lenders and other entities, when complications arise.Brian Kippen and Kacie Merchand grew up in Tunbridge and met in middle school. Brian was living in California in 2011 when he founded a company there, KAD Models & Prototypes. It creates prototypes and models of products in development for clients that make everything from medical devices to wireless chargers; Kacie later joined the company as chief operating officer.

When they wanted to add a secondary manufacturing site to handle more business and build KAD’s East Coast client base, they found the perfect property: A former tractor service center in East Randolph that included three buildings and six acres. It had ample electricity, access for trucks and space for light manufacturing. And nearby, Vermont Technical College could supply advanced manufacturing students as potential employees.

They were ready to buy the property for $365,000, but there was just one problem: cleaners that were commonly used to maintain automotive and industrial equipment had leached into the concrete floor. The new owners would have to pay for remediation.

Brian and Kacie couldn’t clean up the site unless they bought it. But they couldn’t buy it without a loan, and a bank wouldn’t write one for a contaminated site. They were stuck.

The Vermont Agency of Commerce and Community Development connected them with VEDA to underwrite the cleanup costs. KAD received a grant of just over $50,000 from the state’s Brownfield Revolving Loan Fund for remediation.

Then, VEDA made the deal happen. The authority brought in Community National Bank to finance the property purchase, wrote a second loan for the purchase, and arranged for a contingency to ensure cleanup could take place before KAD closed on the sale. Another bank loaned nearly $900,000 for new equipment and expansion expenses.

VEDA coordinated the players, hosting conference calls and sending KAD to additional sources for assistance. VEDA’s involvement acted as a stamp of approval, giving other entities the assurance to work with the company, Brian said.

“They helped us navigate the whole system and were on the phone at times when it was necessary to talk to the state to continue things moving.”

Polhemus acknowledged that its lenders hold hands when necessary. “There’s so much that goes on behind the scenes to bring something to a close,” she said.

Interested in learning more about VEDA loans?

“Without VEDA, this location would probably have zero dollars of revenue,” he said. “So we’ve retained one and a quarter million dollars for the Vermont economy.”

That’s what it’s all about.

find, follow, fan us: