Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

-

News

UVM Cancels Commencement Speaker Amid Pro-Palestinian Protest

-

Education

Education Bill Would Speed up Secretary Search…

-

News

Middlebury College President Patton to Step Down…

- Overdose-Prevention Site Bill Advances in the Vermont Senate News 0

- 'We're Leaving': Winooski's Bargain Real Estate Attracted a Diverse Group of Residents for Years. Now They're Being Squeezed Out. Housing Crisis 0

- Aggressive Behavior, Increased Drug Use at Burlington's Downtown Library Prompt Calls for Help City 0

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

Seven Vermont Luthiers Who Push the Boundaries of Instrument Making

Published May 10, 2023 at 10:10 a.m. | Updated May 17, 2023 at 10:12 a.m.

Pop quiz: Where was the first school for guitar building in North America? If you answered "South Strafford, Vt.," you're either a huge guitar nerd or you were probably a student of pioneering luthier Charles Fox — maybe both. In 1973, Fox opened the Earthworks School of Lutherie, which became the School of the Guitar Research & Design Center, in the tiny Orange County village where he taught an entire generation (or two) of aspiring guitar makers.

Fox moved the school, now known as the American School of Lutherie, to California in 1993 and then to its current home in Portland, Ore., in 2002. But his impact on the field is still evident in Vermont. Look no farther than another Orange County hamlet, Post Mills, where Fox student George Morris has run his own lutherie school, Vermont Instruments, since 1982.

Interest in building (and playing) custom-made instruments has grown both locally and nationally, especially in the past 20 years or so. Precise numbers are hard to pin down, but at least anecdotally, the luthier field in Vermont has exploded.

Nowa Crosby is the owner of Randolin Music Instruments, a Shelburne music shop that moved from its longtime Burlington location last year. He has been building and repairing guitars and almost anything else with strings for 45 years, 32 in the Green Mountain State.

Instrument building in Vermont dates back to at least the early 1900s, Crosby said. "But there's a lot going on right now," he continued. "And the cool thing is that everybody's doing different things."

Indeed. Whether you're on the hunt for a hot-rodded electric guitar, an elegant viola or a dulcet dulcimer, chances are that someone in Vermont builds it, and builds it quite well.

Michael Millard is the semiretired founder of Froggy Bottom Guitars, a Chelsea company that has been at the vanguard of custom handmade acoustic guitars in Vermont since the 1970s. Not that you'll hear Millard boasting of that fact or the elite players who swear by his instruments. Froggy Bottom makes a point of not advertising who plays its guitars, a rarity in an increasingly crowded market.

"Guitars are one of the things in our culture, like fancy cars or motion pictures, that people just get stupidly excited about for no valid reason," Millard said.

There are, of course, valid reasons to get excited about his iconic guitars, which are as pleasing to look at as they are to play or listen to. That's true of the stringed instruments produced by a growing number of Vermonters who are redefining what it is to be a luthier.

"I actually shy away from that term," Millard said. "We make guitars."

Read on for profiles of seven other luthiers — whether they embrace the designation or not — who also make exquisite guitars. And banjos. And mandolins, violins and just about any other stringed instrument you can think of. Building on the groundwork laid by Fox, Millard and others, they're stretching the limits of the trade in Vermont.

— Dan Bolles

Tinkered, Tailored

Micah Plante, owner, Plante Guitar, Bristol

Micah Plante has always been a tinkerer. As a kid growing up in Montpelier, he was blessed — or cursed, depending — with a compulsion to take things apart just to see how they worked. His parents encouraged his curiosity, he said, even if he couldn't always put those impromptu puzzles, or stereo components, back together.

"Answering the question of how things worked often resulted in a broken radio," he confessed.

Plante, 33, is the sole proprietor of Plante Guitar in Bristol. From a small workshop behind his house, he now puts his inquisitiveness to use fixing the electric and acoustic guitars of a loyal legion of local players for whom he's become one of Vermont's go-to repair people. He's also a burgeoning builder whose instruments are noted for their distinctive and aggressive sound — and, in one case, at least, utter uniqueness.

Unlike many luthiers, Plante didn't apprentice with some shamanistic guitar-making guru in the mountains or study under a sainted legend in the field to learn his craft. Largely self-taught, he honed his trade in a more mundane fashion: He worked at Guitar Center in Williston.

Having fixed his own guitars and those of friends since he was a teenager, Plante quickly became the store's leading technician, to the point that the national chain would dispatch him to other regional outlets to lend his expertise or clean up other techs' messes. All the while, he kept up the informal side gig he'd started years earlier as a University of Vermont student in Burlington.

His first workshop had been a dingy Murray Street basement. Later, while dating the woman whom he would eventually marry, he used his one-bedroom Loomis Street apartment as a shop and stayed most nights at her place.

"My apartment was just, like, full of sawdust and stuff," Plante recalled. "There was a spindle sander on the coffee table, every saw you could imagine on the counters." He rigged up a spray booth to paint and finish guitars in the bathroom, because it had a fan that vented outside.

"That was probably not OSHA-approved," he joked.

After living for a few years in western Massachusetts, where he also had a small shop, Plante and his wife bought their home in Bristol in 2018. They currently live there with their young son. Plante spends eight to 10 hours a day fixing guitars and building custom orders in his backyard shop — a converted two-room greenhouse he's renovating to include a small showroom. His guitars typically cost between $2,500 and $3,500.

"I love every different aspect of what it takes to make guitars," he said, his tinkerer's enthusiasm on display. He riffed about woodworking principles and sourcing and tempering wood — one of his instruments, an ultralight 12-fret parlor guitar dubbed "Little Bear," was built from coastal redwood reclaimed from the bleachers at Burlington's Centennial Field. Then he shifted to discussing the machinist aspects of proper fretwork and the guitar gearhead's bottomless rabbit hole: electronics.

"Each one of these is, in itself, a fascinating trade," the former philosophy major opined. "You could have a whole career — and people do — only making pickups. But I can't resist the temptation to be a one-stop shop."

There might be no better example of the alchemy of Plante's all-encompassing curiosity and technical acumen than an instrument he built for Charlotte's Damon Ferrante: a 36-fret tremolo guitar with no headstock.

Most electric guitars have 22 or 24 frets. Ferrante asked Plante to build him one with an additional 12 because the contemporary classical composer was trying to mimic the upper range of a piano, his primary instrument. He mostly unleashes his headless monster in duo projects with Burlington bassist Aram Bedrosian. Between the two instruments, the players have a piano's 86-key range, which opens up a world of musical possibilities, Ferrante explained.

"There is a musical reason for defying what might or might not be possible on the guitar," he said.

On any fretted instrument, the frets are placed closer together the higher you go up the neck. On Ferrante's Indian rosewood and coastal redwood guitar, frets in the uppermost register are almost comically narrow. That creates a challenge for playing the instrument; Ferrante has developed a special technique, since all but an infant's fingertips would be too wide to fit between the highest frets. This also presented design dilemmas for Plante, who compares the guitar's sound to the eerie, ethereal tone of the theremin.

"To Micah's credit, it's such a beautiful-sounding instrument," Ferrante said, adding that Plante's guitars have a forceful and percussive voice "that's unique to him."

While Plante is quick to stress that Ferrante's guitar — and its 27-fret sister, which he also made — is a stylistic departure, it's emblematic of the balance of form and function that he strives for in all of his work.

"I don't want to go too far down the road of being the 'weird guitar guy,'" he said. But "I do like having an original spin on things where there is additional functionality."

— D.B.

An 'Underground Celebrity'

Cat Fox, owner, Sound Guitar Repair, South Hero

Cat Fox was driving through Montana 42 years ago, a college dropout trying to figure out what to do with her life, when she had an epiphany: She'd think of the things she liked to do and find a way to synthesize them into a paying job.

Her list of pleasures consisted of three activities: woodworking (she built birdhouses and rabbit hutches as a kid growing up on an Idaho ranch), partying with friends, and playing and listening to music. Solving the puzzle of how to put these things together, Fox wondered: Do people actually build guitars?

Seeking an answer, Fox pulled her VW bus over in front of a music store in Missoula and asked the man behind the counter: "If a person wants to build guitars, what should they do?"

"Well," he said. "You could do what I did and go to a trade school for that."

The music store guy had learned guitar building and repair at Red Wing Vocational Technical Institute in Minnesota. Fox followed his guidance, applied to the school and was accepted to the one-year program. It was the first step in a four-decade-long journey that included becoming a sought-after luthier and repairperson to the stars in Seattle before semiretirement in Vermont.

"Most of my job is to put the instrument back to what it was," said Fox, now 62 and living in South Hero. "People want it to sound the way it always has and look the way it did before they dropped it on the gravel."

At Red Wing, the course of study ranged from learning how to use certain tools to building a guitar. Fox crafted her first guitar, now played by her daughter, using mahogany for the back and sides and Sitka, Alaska, spruce for the top. The instrument was her "business card," she said, though she initially received a cold welcome from the industry.

After Fox finished the guitar course, she sent out a pile of résumés, including one to George Gruhn of Gruhn Guitars in Nashville. He wrote back: "There's no future in guitars. Get into computers."

Instead, she landed a "no-guarantees" apprenticeship with William Cumpiano, a luthier in Amherst, Mass. Fox packed up her VW bus and moved east, where she repaired and built guitars in Cumpiano's shop for six years, two as an unpaid apprentice.

After a day of luthier work — a stressful job that allows for "no screwing up," she said — Fox worked night gigs as a dishwasher, pizza deliverer and nude model in art studios. Sometimes she started to fall asleep the next day in the instrument shop. "Do you have narcolepsy?" her boss asked — but gave her a paid position anyway.

At the time, he was cowriting his acclaimed 1987 book with Jonathan Natelson, Guitarmaking: Tradition and Technology: A Complete Reference for the Design & Construction of the Steel-String Folk Guitar & the Classical Guitar.

"I was keeping up his brand," Fox said, describing herself as a "ghost-builder." "I got to do lots of repairs."

She was gratified by the work — gluing cracks, replacing frets — and recognized customers' appreciation for it.

"A guitar is an intimate part of people's lives," Fox said. "You have it in your lap."

In 1989, Fox moved to Seattle, where she established Sound Guitar Repair. The name refers to three things: Puget Sound; the sound made by an instrument; and sound work, as in solid, quality, whole. The growth of her business coincided with the burgeoning grunge music scene in Seattle, home of bands such as Pearl Jam, Soundgarden and Nirvana.

Fox didn't repair instruments for musicians in those groups, she said, but she worked on the guitars of Heart's Nancy Wilson and a touring Rosanne Cash. She also made an emergency repair for the Everly Brothers, who were on tour in Seattle when their roadie tripped on a cable while carrying a guitar. He stopped his fall with the headstock, "and the sides cracked open like a crocodile," Fox said.

To fix the guitar in time for the show, Fox was up all night gluing the crack and letting it dry in sections. With each sectional repair, she moved clamps and internal supports called cleats.

"I couldn't get it cleaned up and beautiful, but I made it as good as I could," she said. "I got comped into the show ... It's fun being like an underground celebrity."

Six years ago, Fox and her husband, luthier Rick Davis, moved to a farmhouse in South Hero. She downsized Sound Guitar Repair from a 1,700-square-foot shop to a small room at the back of her house. For $70 an hour, she repairs instruments using three sanders, a drill press and a band saw. Broken guitars are tucked into corners and leaning against walls in their cases, evidence that "semiretirement" isn't quite semi.

Her Vermont customers include Aaron Josinsky, chef/co-owner of Winooski restaurant Misery Loves Co. Fox reset the fretboard on his 1934 Gibson.

"She made it sing," he said.

— Sally Pollak

Banjo Man

Will Mosheim, owner, Seeders Instruments, Dorset

If Will Seeders Mosheim did not make banjos, he probably would have become an engineer. "I'm precision-oriented," he said, standing in the Dorset woodshop he shares with his father, a furniture maker. "It's the way I see things and the way I problem-solve."

Mosheim, 38, launched Seeders Instruments in 2010 and has since built a reputation as a gifted woodworker and engraver who combines traditional craftsmanship with his own style and contemporary techniques. He makes guitars, too, but focuses on five-string, open-back banjos that are known for their playability and tone.

His banjos are visually stunning, featuring meticulous mother-of-pearl inlays and hand-carved details in the wooden necks. With a mom who was a jeweler and gardener and a dad who designs and builds custom furniture, Mosheim almost couldn't help being "artistically inclined," as he describes it.

He plays music, too: banjo and guitar, of course, as well as fiddle, pedal steel and bass. That last one was the first instrument he played professionally, when he was in middle school — he played jazz standards with his brother at Dorset's Barrows House inn on Monday nights. Later he played electric guitar in punk bands Die Like a Champion and Porno Tongue but got "kind of tired of putting in earplugs onstage," he said.

Currently, he's half of the duo Carling & Will with banjo player Carling Berkhout. And he frequently steps in to play with other musicians, such as fiddler and flat-foot dancer Sophie Wellington and 17-year-old banjo prodigy Nora Brown.

But it's putting his hands on the wood — curly maple, walnut, mahogany, ebony — that gives Mosheim the deepest, most consistent satisfaction, not to mention his livelihood.

He started out, in his early twenties, working for his father, Dan, who owns Dorset Custom Furniture. Mosheim had played music since he was 9 or 10 and had been hanging around the woodshop even longer. So it made sense that soon after he picked up the banjo, he wanted to make one himself. He did, with his dad's help. Then he made another — a small "pony" banjo for the child of some friends. He posted a photo of it online and "immediately got three orders from people I did not know," he said.

For a few years, Mosheim built furniture with his dad during the day and made banjos at night and on weekends in between music gigs. He honed his style and technique in workshops with Michael Millard of Froggy Bottom Guitars in Chelsea (see page 26), master banjo builder and engraver Kevin Enoch of Maryland, and Bob Smakula and Andy Fitzgibbon of Smakula Fretted Instruments in West Virginia.

He also traded skills with guitar maker Adam Buchwald of Circle Strings in South Burlington. Mosheim taught Buchwald how to use a CNC — a computer-operated router, essentially — and Buchwald taught Mosheim the craft of making guitars.

Mosheim hasn't made a guitar for a few years, though, because demand for his banjos is so high. Banjo makers number few and far between compared to guitar makers, so "those of us who do banjos are always swamped with work," Mosheim said.

It takes him between 20 and 60 hours to build a banjo, depending on the level of ornamentation. Mosheim produces 20 to 30 a year, both custom orders and those he sells directly to customers online. He also repairs and restores vintage and antique banjos. After teaching himself to use vintage machining and fabricating equipment, he is now able to make about 90 percent of the hardware that his banjos require.

"It takes a little bit of insanity to go this deep," he admitted.

"Will is a bit of a perfectionist," Berkhout said. "He'll do something again and again until he gets it right. He's not afraid to go beyond what everybody else is doing or to really experiment to figure out the best way to create something. He's innovative."

As a result, there's currently a three- to four-year waiting list for one of Mosheim's custom banjos. Berkhout got hers seven years ago: a walnut Dobson Special with a low, mellow sound that's "almost haunting," she said. The banjo has improved with age — "settled into itself," she added. "It sounded really good when I first picked it up, but the more I play it and the more it gets passed around, the better it sounds."

For Mosheim, watching Berkhout and others play his banjos feels like a special kind of collaboration.

"It's like my art goes on to create more art," he said.

He's thrilled that he could make one of his Dobson Special banjos for actor and musician Oscar Isaac, who plays it in the recent Broadway revival of The Sign in Sidney Brustein's Window. Mosheim is also happy to be working on a banjo for the Punch Brothers' Noam Pikelny, a Vermont neighbor and friend who is considered one of the best bluegrass banjo players alive today. And Mosheim was delighted to meet Pete Seeger a year before the folk legend died; Seeger strummed a "longnecker" Mosheim had made and pronounced it "a nice banjo."

Yet Mosheim's mission as a craftsman is not about famous people.

"It's really cool to make instruments for amazing musicians who are in the spotlight, but I don't put any less weight on the person who never takes their banjo out of their living room or who can only play five tunes," he said. "When I get a message or a phone call or an email from someone who says, 'I can't put this banjo down' — that's why I do what I do."

— Jennifer Sutton

Shop Rat to the Stars

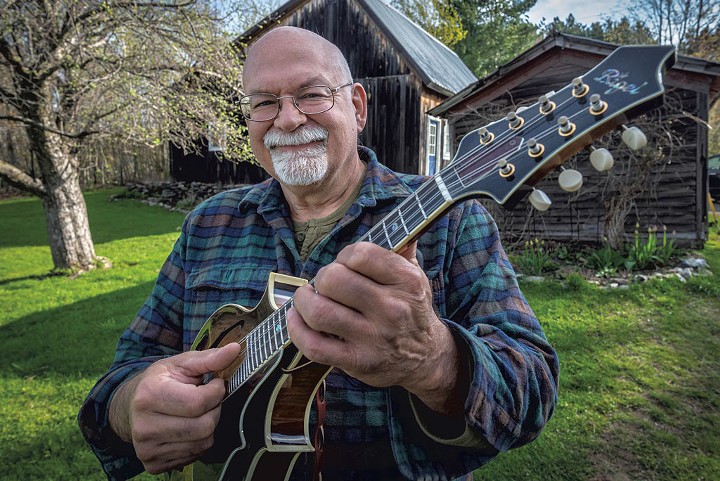

Pete Langdell, owner, Rigel Instruments, Cambridge

In March, Pete Langdell turned on the lights in his workshop, dusted off his tools and started organizing his shop. It felt like he was starting up a spaceship that had been dormant for a while, he said.

Langdell, 65, is a mandolin maker in the Cambridge village of Jeffersonville who put his custom luthier business on hiatus 12 years ago for a steadier gig. The 2008 recession had dried up orders at his company, Rigel Instruments, so Langdell went to work doing "startups" — changing strings, screwing in pegs — and repairs on classical instruments at Metropolitan Music in Stowe.

Recently retired from that job, Langdell is back at work crafting mandolins — the small, eight-string instruments with a big, high-toned sound that first captured his imagination 60 years ago. In that time, he's pioneered an innovative technique for building mandolins and made them for some of the instrument's very best players, including Chris Hillman of the Byrds and the Flying Burrito Brothers and Chris Thile of Nickel Creek.

"Each instrument has its own mystery and charm," Langdell said.

Langdell was 5 years old when he heard someone playing a Sears mandolin at the Waterville Town Hall on a summer Friday night. The show was part of a festive weekly concert of local players — a mini Grand Ole Opry with a house band called the Country Neighbors — that drew a crowd from the surrounding area.

"I was intrigued with the music and mesmerized by the instruments," Langdell said.

The youngest of eight kids growing up on a dairy farm in Cambridge, Langdell attended the summer concerts with his family. Inspired by what he saw and heard onstage, he went home and started teaching himself to make instruments before he was in first grade. He found tools and a workspace in the barn.

"I had that need to do it," he said. "My mother's coffee table was the sacrificial wood."

At Lamoille Union High School in Hyde Park, when other kids in shop class were making cutting boards for their mothers, "I would freak the woodshop teacher out when I said, 'I'm making a guitar,'" Langdell said. "Unbeknownst to me, I was making stuff that not a lot of people could build."

A largely self-taught luthier, Langdell sought instruction from elders in the trade and read all he could about instrument making. "You really, really had to have a desire to know how to do it," he said of learning the skills pre-YouTube. Trying to learn from other makers, "I would wear out my welcome," he recalled.

Not long out of high school, Langdell was working as a machinist in Morrisville and making mandolins on the side. One day he brought one of his instruments to the machine shop. A coworker took a look at it and said, "What in the fuck are you doing here?" Langdell recalled. "You gotta get out of here and do that."

Soon Langdell quit the machine shop, loaded his Jeep with mandos and drove south to MerleFest, a bluegrass festival in North Carolina.

"Everything I brought sold immediately," he said.

Langdell, who calls himself a "shop rat," came back to Vermont and started taking orders for his instruments. He traveled to more music festivals with his mandolins.

"People would see them, play them, touch them," he said. And buy them. At one point, as his reputation spread among musicians, Langdell ran a shop in Hyde Park with eight employees.

He developed a building technique, patented in the early 1990s, by which he could pop the top of the instrument into its sides without gluing it in place. This allows the luthier to "voice the instrument properly," he said, before gluing it permanently.

"It gives you infinite amounts of time [and opportunity] to get the sound you're looking for, the sound you're satisfied with," Langdell said. He also made mandolins in the shape of a Fender Stratocaster electric guitar, imbuing a centuries-old instrument with a contemporary aesthetic.

Langdell, who is also a musician, loves the sound of the double-stringed mandolin, which is tuned like a violin: E, A, D, G. Though each note has paired strings, their tone and pitch are never identical.

"There's a slight discord," Langdell said. "They're sympathetic tones."

Similarly, no two instruments sound the same. "They're like fingerprints," Langdell observed. "All completely unique."

As he wakes up his shop and embarks again on the "hyper-focused" work of building instruments, Langdell said he sometimes has no sense of time when he's making a mandolin.

"I'll forget to eat," he said. "I'll come out in the morning and look up, and it's getting dark."

Langdell's mandolins range in price from $2,500 to $12,000, depending on the model.

"Building an instrument is like playing a game of chess," he said. "You have to think so far out. It's not a fancy cigar box with a neck."

— S.P.

Reeling In the Big Phish

Adam Buchwald, principal luthier, Circle Strings and Iris Guitar, South Burlington

As a guitar and mandolin player, Adam Buchwald knows many different ways to make music. As a luthier, he discovered another: Build a guitar that inspires a musical legend to record an entire album with it.

In 2021, Buchwald, founder of Circle Strings and cofounder of Iris Guitar, was commissioned by Phish keyboardist Page McConnell to build an acoustic guitar for bandmate Trey Anastasio as a surprise birthday present. A Phish fan since he was a teen, Buchwald, 44, leaped at the opportunity. McConnell gave him free rein on the project, and Buchwald pulled out all the stops.

For the top wood, he selected a piece of century-old German spruce, acquired from an 80-year-old luthier who'd built hundreds of guitars and called it "the best-sounding wood I've ever heard in my life." For its sides and back, Buchwald chose chocolate-colored "mother of curl" koa, cut in the 1980s on the island of Oahu from a tree renowned among luthiers. The guitar's neck and bridge were crafted from aged mahogany and ebony.

The finished product proved far more than the sum of its parts. Anastasio was so wowed by the instrument that he and McConnell visited the South Burlington luthier to perform for him and his crew before leaving on tour. Then, during a show at Manhattan's Beacon Theatre, Anastasio gave the luthier a shout-out from the stage. Buchwald, a New York native who'd seen Phish at the Beacon many times, was in the audience that night.

The real kicker came when the Phish lead guitarist used the Circle Strings dreadnought to record his first-ever solo acoustic album, Mercy.

"I've never been in love with a guitar like this before," Anastasio told Guitar Player magazine in July 2022. "It completely changed my music landscape. There would be no Mercy if he hadn't given me that guitar."

A modest and low-key guy, Buchwald said he was always confident he could build a beautiful-sounding guitar. But he never expected that this one would resonate with Anastasio the way it did.

"The fact that he fell in love with it so deeply is priceless," Buchwald said during an interview in his South Burlington retail shop, Ben & Bucky's Guitar Boutique. "I can't even put words to it."

click to enlarge

- Courtesy Of Adam Buchwald

- Page McConnell and Trey Anastasio of Phish at Circle Strings in South Burlington.

Anastasio isn't the only famous musician playing one of Buchwald's guitars. Leo Kottke, Margo Price and Marc Ribot all have one, as do Vermonters Billy Bratcher, Brett Hughes and Zack DuPont.

In recent years, Buchwald has assembled a team of 14 luthiers, nearly all of whom moved to Vermont for their jobs. They are making some of the most sought-after guitars in the industry — and not just for celebrated musicians. Under the Iris label, they're crafting high-quality instruments that don't break the bank with aesthetic extras and expensive customization.

In a sense, Buchwald has come full circle. He first moved to Burlington in the 1990s to study music at the University of Vermont. After graduating in 2000, he returned to New York to work in his father's metal-stamping and tool-and-die factory, which his grandfather founded in the 1950s.

Buchwald hated the work but took advantage of the available tools and equipment to build his first mandolin, guitar and banjo. After 9/11, the factory's products evolved from shoehorns and sponge mops to military hardware. Six years into the job, Buchwald finally called it quits.

He got hired as a repairman at Brooklyn's RetroFret Vintage Guitars, based solely, he recalled, on how he examined one. Then he got married, which changed his view of living in New York City. Buchwald accepted a teaching position at Vermont Instruments, a guitar-making school in Thetford. But teaching wasn't his bag, so he went to work for Michael Millard at Froggy Bottom Guitars in Chelsea.

In 2012, Buchwald returned to Burlington to go it alone at Circle Strings. He shared space for several years with fellow guitar luthier Creston Lea before moving into his current South Burlington spot.

Even before his Phish fame, Buchwald had little trouble selling his high-end six-strings, which now start at $8,500. But in 2018, he saw a gap in the domestic guitar market.

"Most of the musicians I was dealing with were like, 'I could never get one of those [Circle Strings] guitars,'" Buchwald recalled. "'Why can't you make something cheaper?'"

Thus was born Iris, which he cofounded with partner Dale Fairbanks. Iris guitars, which start at $2,200, have the same rich sound and high-quality wood but fewer customizations, upgrades and inlays. But the real cost-saving is in the finish, Buchwald explained, which is less labor-intensive and time-consuming; his team can build an instrument in several days versus weeks or months.

With both Iris and Circle Strings guitars, the craftsmanship is enhanced by the use of well-aged tonewood, or lumber ideally suited for stringed instruments. In 2019, Buchwald bought Allied Lutherie, a California-based tonewood supplier. He moved the company to Vermont and has since bought from other retiring luthiers their stocks of tonewood, nearly all cut decades ago.

"I'm trying to show the world that our guitars are made with material that's been around for a while," he said, "and we're not going to cut more trees down."

For many musicians, too, that has a nice ring to it.

— Ken Picard

The Art of Making Friends (and Guitars)

Creston Lea, owner, Creston Electric Instruments, Burlington

When Creston Lea moved to Vermont in 1996, he was fresh out of college and on a mission to become a writer. "That was my big ambition in life," recalled Lea, the son of acclaimed poet Sydney Lea. "But once I got to town, I started playing in, like, four or five bands at any given time, so I started spending a lot more time with my guitar."

Lea, now 52, loved playing guitars, but he soon realized he knew nothing about how they worked. So he started tinkering with his own, scrounging parts and learning on the fly how to take apart and rebuild the instruments. Already a carpenter with a workspace, he realized one day he was spending more time on guitars than on the cabinets he'd been making.

"In the beginning, every new guitar I worked on presented some new circumstance that I didn't know how to handle," he said. "So I had to learn my way out of those jams."

Once he felt confident enough to move on from his own instruments, Lea built a guitar for local guitar hero Bill Mullins (of Barbacoa), who still plays it. "Thankfully, Bill sounds great no matter what guitar he's playing," Lea quipped with characteristic modesty.

The job that cemented Lea's transition from an inspired amateur to a professional luthier — working under the banner of Creston Electric Instruments — was the commission he received from Mark Spencer in 2003. The Son Volt guitarist and Burlington expat was so pleased with the guitar Lea crafted for him that he emailed his friends pictures to show it off. Soon, other professional musicians were sending orders Lea's way, including such heavy hitters as Ian MacKaye (Minor Threat, Fugazi), Noel Gallagher (Oasis), Val McCallum (Jackson Browne) and Spencer's Son Volt bandmate Jay Farrar.

Those celebrity endorsements did most of Lea's marketing for him; other musicians would see the gorgeous, custom-built guitars — known familiarly as "Crestons" — full of top-of-the-line electronics and innovative designs, and want their own.

"It was a really quick transition," Lea said. "There was about a year where I was still doing some carpentry, but by 2004 I was all in. I remember thinking at the time, Maybe this could work?

"But I had skipped the whole business plan where you go to the bank and find a shop," he went on. "By the time it occurred to me to make guitars for a living, I was already doing it."

What sets a Creston apart is that just about every instrument made in Lea's shop is custom built to specifications, so very, very few of them sound alike. They're often also visually stunning, especially the guitars Lea makes in tandem with local artist Sarah Ryan. On those collaborations, Ryan paints designs on the body of the guitars before Lea sprays clear lacquer over the artwork. Vividly colored flowers, birds in flight, buffalo, deer and even starlit skies populate the instruments.

According to Lea, the diverse needs of his customers help keep his brand eclectic.

"I don't have to be very deliberate in trying to make my guitars different, because all of the people ordering them want such different things," he said. "And if somebody asks me to make them a guitar that looks or sounds like something you might find on a rack at a Guitar Center, I just say a polite 'No, thanks.'"

Crestons aren't considered guitars for beginners or the casual player — Lea's axes typically go for between $2,900 and $3,600. But he finds his customer base both varied and growing.

"I make as many guitars for 70-year-old men who stay at home and play blues as I do for younger players that reference bands I've never heard of," Lea said.

The days of Lea having to learn his way out of problems are over, for the most part. But that doesn't mean the trade is easy for him.

"It seems like there are 10,000 steps to making a guitar, and you can blow the whole thing by messing up any of them," he said with a rueful laugh.

After almost two decades of guitar making, Lea found himself in something of a professional slump last summer. Then he caught a My Morning Jacket show in Shelburne. The band's bassist, Tom Blankenship, had commissioned several bass guitars from Lea.

"It felt so good when I heard the band over those huge speakers, and Tom's bass was so big and loud," Lea recalled. "He played the basses I made him for the entire show. It just really pulled me up and out of that funk."

Lea did get around to fulfilling his writing ambitions — his collection of short stories, Wild Punch, came out in 2010 — and the future of Creston Electric Instruments looks bright.

"I read this book by [local author] Tim Brookes called Guitar: An American Life," Lea said. "He talks about how, really, the guitar should have died off by now. But instead of disappearing, it just became more and more iconic."

When asked if keeping the guitar relevant is part of his mission, Lea chuckled.

"I don't worry about that, honestly," he said. "I've made a lot of really cool friends by making them guitars, and that's what I really look forward to. Just making new friends."

— Chris Farnsworth

The Sweet Sound

Marit Danielson, luthier, Vermont Violins, South Burlington and West Lebanon, N.H.

Marit Danielson has been making violins by hand for 25 years, and luthiers like her have been doing so since the early 16th century. Nevertheless, the craft remains mysterious. "You don't know what [a violin] is going to sound like until it's done," Danielson said.

The Peacham resident spoke at Vermont Violins' West Lebanon, N.H., shop while shaping a front plate's arch with a finger plane. As she formed the flat piece of spruce wood into a contoured bubble, shavings fell on her Norwich terrier, Bromley, a constant companion.

Like her predecessors of the past five centuries, Danielson has been experimenting with minute changes in violin design — to the front plate's arch and thickness, the size of the f-holes, the origin of the woods used, and myriad other variables — since she trained at Boston's North Bennet Street School and apprenticed with Joseph Curtin and Gregg Alf in Ann Arbor, Mich. (Curtin is still at the forefront of the field in the U.S.)

One thing, however, is unusual about her practice: She's a woman.

As Kathy Reilly, co-owner of Vermont Violins, said, "It is such a traditional field that people subconsciously or unconsciously are less likely to purchase a violin made by a woman."

The shop sells Danielson's handmade violins for $14,000 alongside its mid-level V. Richelieu line (priced from $5,000 to $7,000) and $600 Chinese-made instruments.

Reilly estimates that 40 percent of luthiers today are women, "but they tend not to be recognized." Last year, as a countermeasure, she mounted a traveling exhibition of women luthiers' instruments from Europe, Canada, Mexico and the U.S. — including Danielson's, the only example from Vermont.

Danielson was hired at Vermont Violins a decade ago, as its first female luthier, to start the Richelieu line. She made the line's models and helps hand-finish the instruments in the West Lebanon store. (She makes her own violins at home.)

Richelieu instrument plates and scrolls are cut on a hulking 2-year-old CNC machine in the store's South Burlington location — a method already being pursued in Germany, Romania and the Czech Republic to save on labor costs, according to Reilly, who showed Seven Days around the production floor.

Today, five of Vermont Violin's nine instrument makers are women, including the newest, Claire Rowan. At the South Burlington store, the Richelieu work line included three of them. Young-Ju Kim was inserting the purfling — an impossibly thin black strip made from layered maple wood — into the channel outlining a front plate. Rowan was carving a bridge, which supports the strings above the fingerboard. And Xiu Ling Stein was mixing and applying varnishes.

Danielson, however, is the only luthier among them who makes her own line of violins. She came to the craft indirectly, as a musician. Growing up in Peacham from the age of 11 — her current house is within sight of her childhood home — she played violin and viola "pretty seriously." She started college at the Manhattan School of Music, majoring in music performance for viola, but found the New York City scene too competitive and switched to Bryn Mawr College in Pennsylvania, where she earned a degree in art and philosophy.

While working in Boston after graduation, she heard about the violin-making program at North Bennet. "Something clicked in my mind," she said. Though she'd had no hand tool experience and "couldn't even sharpen a knife," she had always been good at creating things with her hands.

During the two-year program, Danielson attended a talk about acoustics by Curtin and Alf at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. She approached them after and landed an apprenticeship.

In Ann Arbor, Danielson recognized right away that the men's instruments looked more like the old Italian instruments, which are still played, than anything she had learned to make in school. "All the finer details — the carving, the curves, the varnish colors that they had captured somehow" — made their instruments superior. "That was where I was able to train my eye," she said.

Nina Kim, a freelance violinist in Tampa who plays mainly with the Florida Orchestra, is one of Danielson's happy customers. Kim first learned of Vermont Violins while attending the Green Mountain Chamber Music Festival in Colchester as a master's student in 2015. Two years later, while earning her doctorate at the University of South Florida, she needed to upgrade her instrument and asked Reilly to mail her some options.

Of the three sent from Vermont Violins, Kim recalled in a phone call, "I liked Marit's the most. The sound was so beautiful. It has a sweet sound" — an actual descriptive term violinists use. Kim also needed a "more powerful [instrument] with a bigger sound" for upcoming solo concerto performances, and Danielson's fit the bill. Kim's colleagues heard it in different halls and admired its "projection, timbre and color," she said.

Choosing a new violin is tricky, Kim added: "There are billions of violins in the world, and every single one is unique."

Danielson noted that the past 20 years have seen a renaissance in contemporary violin making in the U.S. "Schools are training kids better, makers are being less secretive, and the instruments are much better," she explained. There are even acoustic conferences where technicians measure how minute differences in arches affect sound.

But, she added, "Violin makers still feel like they're puzzling it out. Why can't you just re-create this and know what it's going to be every time?"

— Amy Lilly

The original print version of this article was headlined "String Theories | Seven Vermont luthiers who push the boundaries of instrument making"

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

Tags: Music Feature, Seven Days Aloud, Seven Days Aloud, Seven Days Aloud, Seven Days Aloud, Seven Days Aloud, Seven Days Aloud, Seven Days Aloud, Seven Days Aloud, Seven Days Aloud, Seven Days Aloud, Luthiers, Micah Plante, Cat Fox, Will Mosheim, Pete Langdell, Adam Buchwald, Creston Lea, Marit Danielson, Seven Days Aloud, Video

find, follow, fan us: