Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

-

Education

Scott Official Pushes Back on Former State…

-

News

Burlington Budget Deficit Balloons to $13.1 Million

-

Education

Senate Committee Votes 3-2 to Recommend Saunders…

- Court Rejects Roxbury's Request to Block School Budget Vote Education 0

- Norwich University Names New President Education 0

- Media Note: Mitch Wertlieb Named Host of 'Vermont This Week' Health Care 0

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

A New Wave of Vermont Distillers Pushes Legislators to Modernize Liquor Laws

Published November 17, 2021 at 10:00 a.m.

Vermonters buy a lot of Barr Hill Gin. So much, in fact, that Caledonia Spirits' award-winning gin — distilled from Vermont honey on Gin Lane in Montpelier — was the third-highest-selling liquor in the state of Vermont between July and October 2021.

What beat it out? Two different sizes of Tito's Handmade Vodka, a self-described "craft-distilled" national brand whose scale far surpassed any reasonable definition of "craft" or "handmade" a couple of decades ago. Barr Hill was the only Vermont-distilled product to make the top 25.

When Todd Hardie launched Caledonia Spirits in Hardwick in 2011, Seven Days called his team "participants in a modern distilling revival in Vermont." At the time, 14 businesses were licensed to distill in the state, up from three in 2004.

"Within a decade, Vermont may well be known as a craft-distilling epicenter," the story predicted.

But a decade later, is it?

Vermont has 26 licensed distillers today. That, and the scene on Gin Lane on a recent Saturday, would hint yes. Like bees to honey — or honey-based booze — locals and tourists alike swarmed to Caledonia Spirits' bustling tasting room. They waited in a line out the door to sip Tom Cat old-fashioneds, barrel-aged negronis and, yes, bees' knees.

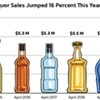

Alcohol sales as a whole increased during the pandemic, including a 13 percent spike in liquor sales, according to the Vermont Department of Liquor and Lottery. That pandemic bump, driven largely by sales of national brands, even led to a liquor shortage this past summer.

Still, it's been a hard time for Vermont's distillers. In addition to retail sales at liquor stores, many rely on out-of-state tourism to fill tasting rooms that have been largely shuttered for the past 20 months.

In May, Caledonia Spirits president and head distiller Ryan Christiansen testified before the Vermont House Committee on General, Housing and Military Affairs, which considers matters related to alcoholic beverages. He painted a bleak picture of the industry.

"Our distillers are struggling," he said.

Christiansen urged the committee to consider an amendment that would allow Vermont's spirits producers to ship their products directly to consumers. Under Vermont's control-state model, the state strictly manages the distribution and sale of liquor. Distillers can sell directly to customers at tasting rooms and farmers markets. Otherwise, their products are only available through state-contracted 802 Spirits liquor stores.

Like most Vermont distilleries at that point in the pandemic, Caledonia Spirits was closed to the public. So access to customers — especially those in big, lucrative markets out of state — was "virtually gone," Christiansen said.

"You know how powerful tourism is in our industry," Christiansen said. "If you take that away, it's pretty brutal."

Large national companies that specialize in shipping booze to customers' front doors were skirting Vermont's system.

"It's irresponsible to ignore that we've lost control of our control state," Christiansen said.

Vermont's liquor control system, like similar ones in 16 other states, is a product of Prohibition — or at least the end of it. When the Volstead Act was repealed on December 5, 1933, the states had to figure out how to sell booze. Most opted for a license-state model, which leaves sale and distribution to the private sector. Vermont opted for a stricter approach, which was unsurprising.

In 1853, nearly 70 years before Prohibition started in 1920, Vermont became the second state in the nation to outlaw alcohol — following Maine, where the temperance movement began. Alcohol was illegal in the Green Mountains until 1902 — hence Vermont's robust history of smuggling.

To this day, the state's Division of Liquor Control — part of the Department of Liquor and Lottery — is responsible for the sale of hard liquor at the wholesale level, contracting with 78 agency stores and setting prices. However, beer and wine are distributed by private-sector wholesalers and available at almost any gas station or grocery store — currently some 907 locations throughout Vermont.

Vermont's statute, Title 7, lays out very different rules depending on whether people make wine, beer or spirits, noted Wendy Knight, who was appointed deputy commissioner of the DLC in April 2021. Knight served as the commissioner of the state's Department of Tourism and Marketing from 2017 to 2019. "And what I've heard over and over, since 2017, is a desire to have parity," she said. Historically, spirits were viewed as more dangerous due to their higher concentration of alcohol.

But a new wave of distillers is setting up shop in Vermont. They're sourcing local ingredients, looking to promote tourism and creating innovative ready-to-drink products. And they are increasingly calling for the state to modernize the laws they say are holding them back and preventing growth in the industry.

"I think public servants need to be open to fresh thinking," Knight said.

Canned Response

A new product from WhistlePig farm and distillery hit the shelves last month. But if customers look closely at which shelves, they'll notice that the four-packs of PiggyBack Rye Smash cans are widely available anywhere beer and hard seltzer are sold, rather than only at liquor stores with other canned, ready-to-drink (RTD) cocktails made by the likes of Absolut Vodka and Jack Daniel's.

When this reporter placed a pack each of the three PiggyBack Rye Smash varieties on the counter at Vergennes Wine & Beverage — which sells liquor through one point-of-sale system as an 802 Spirits outlet, and beer and wine through another — the cashier remarked, "I don't know which register to use."

The RTD beverages are made from rye grown on WhistlePig's Shoreham farm combined with barrel-aged fruit. The goal: to "take a cocktail that is traditionally rye and bring it into a can in a more sessionable drink," said Meghan Ireland, WhistlePig's chief blender — meaning you can have a few over time and not get blitzed.

Ireland spent a year behind the scenes developing the 8 percent Blackberry Lemon Fizz, Session Citrus Mint and Fresh Ginger Lime flavors. The result is something you'd want to drink while basking on a boat or next to a roaring bonfire: refreshing and gulpable.

Besides the fruit, the key difference from WhistlePig's typical rye whiskey products is the base: "It's malt-based," like beer, Ireland said, not spirit-based. The rye flavor is there, but without the typical whiskey bite.

That distinction means that, also like beer, PiggyBack Rye Smash can be sold in hundreds of locations and gets WhistlePig's name out in front of new customers. "Seeing it in my Hannaford now is super weird," Ireland said. "I do a double take when I'm walking around the store."

The RTD cocktail category was growing steadily before rising sharply during the pandemic, Deputy Commissioner Knight said. In 2019, 6,300 cases of RTD beverages were sold. That figure shot up to 10,581 cases in 2020: a 69 percent difference. By comparison, sales of all spirits combined grew by 7.6 percent in the same period.

"And we're not seeing that growth let up," Knight added. With the holidays still to come, cocktail category sales are already well over 12,000 cases in 2021.

"During the pandemic, consumers were not able to drink their cocktails at their favorite local bar or restaurant, so they started drinking them at home," she said.

Premixed RTD cocktails take the guesswork — and the measuring, shaking or stirring — out of home bartending. They're conveniently packaged in containers that are easy to take on the go, and many have a lower alcohol content compared to full-strength cocktails, which can hit 35 percent if you're sipping a dry martini.

According to a June 2021 report from California-based Grand View Research, the global RTD cocktail market was valued at $714.8 million in 2020. It's expected to grow by 12 percent annually over the next seven years, with canned products increasing the fastest and spirit-based products holding the largest revenue share.

"Changing lifestyle choices to improve health and the trend of responsible drinking is expected to boost the product demand," the report stated.

The rising local demand for RTD spirit cocktails such as Mad River Distillery's maple-cask rum, bourbon and rye-based old-fashioneds, as well as demand for their malt-based cousins, is presenting new challenges for legislators — not to mention liquor store clerks.

"You have this convergence of the malt and spirits sectors," Knight said. "It's causing us, as regulators and legislators, to really rethink how we approach the tax and regulatory framework."

Out of Control?

WhistlePig's new PiggyBack Rye Smash fits the growing consumer demand for lower-alcohol RTD canned products. But to reach new grocery store outlets, the distillery had to develop an entirely separate production process so that the beverage would fit within the state's rigid distribution guidelines.

"Vermont spirits manufacturers are pushing to have canned low-alcohol, spirit-based products be distributed outside of the DLL," Rep. Matt Birong (D-Vergennes) told Seven Days in June. "They'd like to expand their product lines, but only being able to sell in roughly 80 stores instead of [a] thousand is super limiting to their market."

Last session, Birong sponsored a bill, H.313, which extended pandemic to-go cocktail sale provisions for two years, among other alcohol-related modernizations.

Another bill that would allow these products to be distributed and sold as widely as beer and wine was a hot topic during the most recent legislative session. Introduced by Rep. Tommy Walz (D-Barre City) in 2020, H.178 (and the concurrent S.68 introduced in the Senate) proposed creating a new category within Title 7 defining "low-alcohol spirits beverages" as between 1 and 16 percent alcohol, packaged in metal cans containing fewer than 24 fluid ounces.

Walz described the bill as a "product of how fluid the market is and all the creative stuff that's going on."

In a meeting of the Senate Economic Development, Housing and General Affairs Committee in April, former deputy commissioner Gary Kessler testified that removing these products — and a growing category — from the DLC system would represent about a $300,000 loss in net revenue for the department. (The DLC grossed $87.9 million in fiscal year 2020 and contributed $31.8 million to the state's general fund.)

"That's a very territorial view," Knight said. "I look at it more broadly: Just because you might take RTDs out of the DLC doesn't mean you're not going to recoup [that revenue]."

Sales and excise taxes would still be in effect, she noted, and with more than 2,000 new potential retailers, the numbers would be "basically a trade-off of revenue."

"And guess what?" Knight added. "If you're helping the private sector grow, then you're going to see [increases in] property taxes, business taxes and personal taxes, too."

At least seven control states, including New Hampshire and Maine, let licensed wholesalers distribute spirits-based RTDs.

Clare Buckley, who represents the Vermont Wholesale Beverage Association, testified that a similar change here would keep Vermont's retailers competitive with border states, while providing distillers with the scale they need to succeed financially and create jobs and tourism opportunities — just as craft beer has.

And there's precedent for similar legislative change in the beer world: In 2008, at the urging of the Vermont Brewers Association and others, the state raised the cap for selling high-alcohol beers outside of the DLC from 8 to 16 percent — meaning those beers could be sold in grocery stores.

Some legislators were concerned that RTDs might be more attractive to young consumers, due to their array of sometimes sweet, fruity flavors. But the biggest sticking point among legislators and within the various beverage industry representatives was whether 16 percent is really "low-alcohol" and whether a different cap — either 8, 10, 12 or 14 percent — would be more appropriate.

That's where the legislature left off at the end of the last session and where they'll pick things up again in 2022, Rep. Birong said — along with the question of direct-to-consumer shipping.

At ArtsRiot in Burlington, that legislative delay created more time for research and development. Canned cocktails are a huge part of owner Alan Newman's plan for the business' new distillery. But as Newman told Seven Days in May, he's "not a fan of the control-state concept" and has no "real interest in selling through the DLC."

A cofounder of Magic Hat Brewing and a charter member of the Vermont Brewers Association, Newman is no stranger to tussles with the state over alcohol regulations.

"Frankly, if Vermont doesn't change the law, I'm going to have to go to another state that doesn't have control to allow me to invest enough money with the chance of recouping it, because I'll have the chance of getting scaled," Newman said. He's biding his time to see what the legislature does in the next session.

In the meantime, distillery general manager Joe Buswell is taking advantage of the takeout cocktail extension, developing canned, lower-alcohol versions of popular cocktails on the ArtsRiot menu and selling them at the restaurant and to-go.

"We're saying, 'OK, what of those successful drinks can we translate to get in front of people when they can't have a six-ingredient cocktail?'" Buswell said. "And that's the fun part."

The distillery is not yet up and running due to construction and shipping delays. Eventually, it will have a 45-gallon still and a 200-gallon still set up in the former South End Arts + Business Association office attached to ArtsRiot. For now, Buswell is playing with ingredients from the restaurant's bar and canning them in-house on a bench-top canner.

Drawing on his experience working for Caledonia Spirits and with other Vermont distillers, Buswell has landed on a handful of cocktails that feel "dialed-in," including the Free Spirit, with tequila, crème de cassis, ginger juice, lime and agave; the Queen Rhubee, with gin, lemon, honey and a rhubarb-hibiscus-angelica root soda made by Jess Messer of Savouré in Bristol; a whiskey highball with "bourbon and H2O"; and a take on the trendy Ranch Water combo of tequila, mineral water and lime.

The operation on Pine Street is intended to be small — a "lab for experimentation," Buswell said, following the brewpub model. Right now that means about 300 slim, 12-ounce cans at a time. "And that's a monster run," he added with a laugh.

The Weight of Water

When Buswell fires up the stills at ArtsRiot, the distillery will join Burlington's Pine Street urban beverage mecca, which also includes Zero Gravity Craft Brewery, Queen City Brewery and Citizen Cider — not to mention Switchback Brewing and Burlington Beer on nearby Flynn Avenue. But the industry's rural connections are growing, too.

A group of farmers, distillers, brewers and legislators is currently preparing a bill for the upcoming session that would support the expansion of on-farm distilling and brewing in the state.

"Farming and distilling go way back," said Emily Harrison, WhistlePig's distillery manager and one of the advocates working on the bill. "Historically, it was a process where the farmer could ferment their grain — and either make beer or make distillate — and feed the waste to their animals."

That cyclic process was cut off during Prohibition, Harrison explained. On-farm brewing and distilling would help bring it back and encourage farmers to grow more barley, rye, corn, hops, botanicals, and other brewing and distilling ingredients.

"The success of the Vermont craft brewing and craft distilling industry could help support Vermont farms in this harmonious way, and that would help support the state's healthy working landscape," said Jacob Keszey, the farm and land director at Nordic Farm in Charlotte, who is also working on the proposed legislation.

Rep. Birong introduced legislation, H.781, in January 2020 to create a separate "farm-based manufacturer's license" for brewers, vintners and distillers who are "located on a farm and produce beverages that are made a majority by weight from ingredients produced by that farm."

Farm-based distilling has fueled growth in the craft spirits industry in New York State for more than a decade. In 2007, New York lawmakers passed the Farm Distillery Act, creating a new license for distillers producing fewer than 75,000 gallons per year while using at least 75 percent New York State ingredients.

That legislation, along with the state's 2014 Craft Act, lowered the barrier to entry for farm distillers: If they meet both the size and sourcing requirements, the license fee is $938 for 36 months, instead of the $50,800 required for a Class A distiller's license — and they can label their products "New York State liquor." As of November 9, the New York State Liquor Authority lists 161 active farm distillery licenses.

With New York's model, and other nearby states such as Connecticut and Massachusetts adopting on-farm distilling laws of their own, Vermont legislators have plenty of inspiration close to home.

One challenge that the updated legislation will address is unique to Vermont, though. A 2015 Vermont Superior Court decision ruled that, when determining whether whiskey is an agricultural product, water counts — and water isn't a farm-produced ingredient.

"That puts people who use grain as one of their main inputs at a disadvantage, because water has to be added to grain in order to make it a liquid," Harrison explained. That's a stark contrast with cider and wine, where the liquid comes naturally from apples or grapes.

The court decision was the result of an Act 250 appeal by WhistlePig and its founder Raj Bhakta, who is no longer associated with the company. Bhakta was seeking an agricultural exemption from the Act 250 permitting process for WhistlePig's farm and distillery in Shoreham. In order to get it, the company needed to prove that more than 50 percent of the ingredients in its farm-distilled rye whiskey were grown or produced on the farm.

Water is essential to the malting and mashing steps of distillation and is used to dilute the spirit to reach the desired proof before bottling, unless the product is at undiluted cask strength. So counting it as an ingredient would make it nearly impossible for distillers to produce a grain-based spirit that fits the "agricultural product" definition. Even WhistlePig's recently released Beyond Bonded FarmStock Rye, which is the distillery's first product made entirely with rye grown on its 500-acre Shoreham property, wouldn't qualify.

Grain to Glass

Beyond the existential water question, Keszey and others are also looking at incentivizing the stuff that would count for distillers and brewers: Vermont-grown ingredients.

In New York, farm distillers are required to use at least 75 percent state-grown ingredients. In Connecticut, 25 percent of ingredients must be grown on-farm. Vermont is exploring how to incentivize local ingredients, but details are still TBD. Any incentives should take into account how much Vermont's farmers can grow and how ancillary businesses like the malthouse at Nordic Farm can fulfill the demand. Flexibility will be key, Harrison and Keszey acknowledged.

"You've got to keep in mind — and we've experienced it at WhistlePig — you have bad crop years; you have good crop years," Harrison said. "You don't want to disincentivize the farmer or the distiller from trying new, more sustainable crop methods and doing what's right for the land, even if it's sacrificing some yield."

"With the decline of dairy, we need multiple new market sectors to grow to replace it if we're going to have all of our farms employed," Will Raap, the founder of Gardener's Supply and the Intervale Center, told Seven Days. Raap is in the process of purchasing Nordic Farm and aims to close on the sale in mid-December.

"Nordic is the epitome of a challenge that many farms in Vermont have, but it's exaggerated," Raap said. His vision for the conserved 580-acre former dairy on Route 7 in Charlotte with its 40,000 square-foot malthouse involves hosting a "multiplex" of agricultural businesses on-site — including a WhistlePig tasting room.

Combining on-farm distilling with agritourism offerings — the classic combination of tasting and tour — is also an important path forward for farm viability, Raap said. About 55,000 cars a day roll past Nordic Farm's red-roofed hilltop barn; he hopes to draw a few in to taste the whiskey, see rye growing in the fields, check out the malthouse and learn about the process from seed to sip.

"Like a mini Ben & Jerry's ice cream factory," Raap said.

Distilling is "the fifth or 10th new market that has developed in support of the new Vermont agriculture," he added. But it fits the Vermont brand, and "with high margins and value-added [products], that's the only way we get to be a farm state long-term."

In Rep. Birong's mind, opportunities for the distilling industry parallel Vermont's success with local food over the past 20 or so years, especially in promoting tourism to tasting rooms and production facilities, whether they're in majestic rural areas or in town centers.

Said Birong: "It's an easy marketing transition to be like, 'We do all this with our beer industry, our food or agriculture. But hey, check out what we're doing with spirits, too.'"

Revved Up: Village Garage Parks in Downtown Bennington

When Glen Sauer first shared his distillery dream at a family dinner on Christmas Eve of 2018, it was more a joke about making moonshine in the garage.

"I said, 'I'm going to tap all the maple trees on our hill, figure out a way to make white lightning with the sap, sling it out of my '54 Chevy sedan and be an outlaw," Sauer recalled.

"That wasn't such a great idea with a wife and two kids," he continued, "but from across the table, my wife's uncle just gave me a look."

As it turned out, that uncle, Matt Cushman, shared Sauer's dream — though his version was a retirement plan filled with 10-year-old bottles of bourbon.

Three years later, Sauer and Cushman have set up shop at Village Garage Distillery in downtown Bennington. After a meticulous renovation, they've turned an old garage that housed highway equipment into the state's newest distillery and the only one operating in Bennington County.

Both cofounders are Bennington natives and eighth- or ninth-generation Vermonters, depending on whether you count the time when New York and New Hampshire were still fighting over the state, Sauer joked.

The rest of the Village Garage team, head distiller Ryan Scheswohl and head of customer experience Alex von Pfeiffer, are recent transplants. Scheswohl came to Bennington from his native Pennsylvania, where he was a distiller at gin-focused Philadelphia Distilling. Von Pfeiffer, who will run the distillery's on-site tasting room, is from Australia by way of New York City — and some of Manhattan's most respected bars.

Now, they each live within blocks of the downtown distillery. For von Pfeiffer, the setup is almost too quaint and perfect. He jokes that he's waiting for the ceiling tile from The Truman Show to hit him and snap him out of his idyll, especially as he watches Sauer make his preferred old-fashioned handshake deals. "To me, this is life imitating art," he said. "I grew up watching American movies, and when my family and I moved in here, the neighbors were knocking on the door with cookies. People wave in the car — it's what's on the brochure."

Bennington's location in southwestern Vermont is convenient for tourists — roughly three hours from New York City or Boston. But until recently, Bennington County's craft beverage culture has lagged behind the rest of the state. Now, Bennington has three breweries, Village Garage and a cidery soon to open.

"It's going to be a turning point and an upswing for this southwest corner," Sauer said. "Geographically, we're the gateway. If you're coming up to go to the ski resorts, we're right here. We want to get people back into our downtown to let it thrive again and just make it fun."

Village Garage's first release — a bourbon made with a 60-40 blend of Vermont corn and rye — came out of the still long before Sauer and Cushman's fateful Christmas dinner. It's been aging in American white oak barrels for five years.

Because the aging process for whiskey takes years, sourcing is common practice for startup distilleries. Nora Ganley-Roper and Adam Polonski of Lost Lantern Whiskey, an independent bottler based in Weybridge, helped Village Garage find the bourbon at a distillery in northern Vermont when it was 3 years old.

"We moved it home and just continued the same recipe to keep things consistent," Sauer said. "So that's how we've got stuff in bottles now. We love it, and we love that it's never left the state."

The bourbon has a peppery spice thanks to its high rye content, but the corn's sweet, smooth notes are still front and center. The 13 scattered stars of the Green Mountain Boys flag are on the label, driving home the product's Vermont roots.

The distillery has started barreling its in-house bourbon, and bottles will hit the market in a few years "when they feel right," Scheswohl said. Village Vodka is available now; Village Rye Whiskey and a smoked-maple American whiskey are next to be released.

The tasting room attached to the distillery has yet to open due to pandemic-related equipment delays. When it does, Scheswohl will make small batches of "fun stuff," including gin, rum, absinthe, amari and herbal liqueurs to supply the bar. Village Garage is currently open for bottle sales — just knock on the garage door.

The 75-seat tasting room space has a view into the distillery, and tours will be a big part of the business, von Pfeiffer said.

For Scheswohl, Village Garage's biggest draw is the opportunity to craft spirits using local ingredients. He's been distilling four times a week for about four months now, using water from nearby Bolles Brook and a four-day, open-top fermentation to capture unique flavors and acid profiles of wild yeast before distilling with the 500-gallon Vendome copper still.

All the corn and rye that Village Garage uses is sourced from Grembowicz Farm in North Clarendon. "I asked for 70,000 pounds of rye — it's a 600-acre farm, so they have more than enough to supply us — and we're locked in, locked and loaded," Scheswohl said. "They see the value in selling to the industry here, and hopefully we can turn other people on to it, too, to help them out."

The original print version of this article was headlined "Lifting Spirits"

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

About The Author

Jordan Barry

Bio:

Jordan Barry is a food writer at Seven Days. She holds a master’s degree in food studies and previously produced podcasts about bread and beverages.

Jordan Barry is a food writer at Seven Days. She holds a master’s degree in food studies and previously produced podcasts about bread and beverages.

More By This Author

Latest in Business

Related Locations

-

ArtsRiot

- 400 Pine St., Burlington Burlington VT 05401

- 44.46810;-73.21474

-

802-540-0406

802-540-0406

- www.artsriot.com…

-

Barr Hill

- 116 Gin Lane, Montpelier Barre/Montpelier VT 05602

- 44.25045;-72.56662

-

802-472-8000

802-472-8000

- caledoniaspirits.com

-

Earthkeep Farmcommon

- 1211 Ethan Allen Hwy, Charlotte Chittenden County VT 05445

- 44.33574;-73.23431

-

(802) 425-2283

(802) 425-2283

-

Mad River Distillers

- 89 Mad River Green, Mad River Taste Place, Waitsfield Mad River Valley/Waterbury VT 05673

- 44.18426;-72.83829

-

802-496-6973

802-496-6973

- www.madriverdistillers.com…

-

WhistlePig Farm

- 2139 Quiet Valley Rd., Shoreham Middlebury Area VT 05770

- 43.91130;-73.27659

-

802-897-7700

802-897-7700

- www.whistlepigwhiskey.com…

Related Stories

Speaking of...

-

Crumbs: ArtsRiot Space for Lease; Jones the Boy Closes Bristol Retail Bakery; 'Seven Days' Makes Late-Night TV

Oct 18, 2023 -

Appalachian Gap Distillery in Middlebury Switches Ownership

Sep 26, 2023 -

Wild Hart Distillery’s New Shelburne Tasting Room Offers Cocktails and Atmosphere

Aug 15, 2023 -

Best spirits distiller

Aug 2, 2023 -

ArtsRiot to Host Location of PlantPub, a Massachusetts Vegan Restaurant

Mar 23, 2023 - More »

find, follow, fan us: