Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

-

Education

Scott Official Pushes Back on Former State…

-

News

Burlington Budget Deficit Balloons to $13.1 Million

-

Education

Senate Committee Votes 3-2 to Recommend Saunders…

- Court Rejects Roxbury's Request to Block School Budget Vote Education 0

- Norwich University Names New President Education 0

- Media Note: Mitch Wertlieb Named Host of 'Vermont This Week' Health Care 0

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

After the Fire: Envisioning Vermont's Post-Pandemic Future

Published May 13, 2020 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated May 20, 2020 at 10:12 a.m.

The cascading coronavirus crises come at us so quickly these days that it can be challenging to keep up with the current news cycle, let alone consider the next.

Our collective attention is rightly focused on the spread of COVID-19, which has contributed to the deaths of 53 Vermonters and infected more than 925. It's rightly focused on outbreaks in long-term care facilities and prisons, on idled factories, bankrupt businesses, unemployment claims, emergency food lines, and the fiscal solvency of our schools and our state.

But what comes next for Vermont — in six months or in six years? In what state will we find our state once the pandemic has passed?

Gov. Phil Scott has compared the outbreak to a forest fire. Regular testing of the potentially infected "will allow us to spot those embers early," he has said, and contact tracing by public health officials will enable us "to surround it in order to contain it."

How long the fire will smolder is anybody's guess. When it's finally extinguished, will it have taken the forest with it? Or will it have cleared the underbrush and opened the canopy, allowing the trees that remain to grow taller and stronger?

For this week's issue, we asked 15 Vermonters — community leaders, business chiefs and experts in their fields — to consider the fate of the state after the fire is out. Will our small towns and small businesses survive? How will we safely gather and learn and celebrate? Will we seize the opportunity to strengthen our health care and food systems? What must we save, and what can we afford to lose? How can we turn tragedy into opportunity?

Here are excerpts from those conversations, edited for clarity and length.

Cause for Panic

When Heather Darby was growing up on an Alburgh dairy farm, there were more than 3,000 dairies in the state. Now there are 651, according to the Agency of Agriculture, Food and Markets, with many expected to close this year..

"It's devastating," she said. "We shouldn't be allowing the loss of any farms in Vermont."

A professor of agronomy at the University of Vermont Extension, Darby finds herself disconsolate about the perverse pair of crises exacerbated by the pandemic: Vermonters are going hungry even as farmers dump milk and plow under their fields. "It's like, Holy shit. What's wrong with this picture?" she said. "We've set up a system that doesn't necessarily feed families. It feeds restaurants. It feeds wholesale markets. It wasn't at all prepared to then have to flip a switch and feed families."

Darby, who is 45 and runs the now-diversified family farm, says the state must "refocus quickly to figure out how to feed the people of Vermont." She added, "Empty store shelves should be worrisome, but empty fields should be cause for panic."

What can we be doing right now?

We can be helping farmers adapt to the growing need for food.

I own a farm. I can't just start doubling production today, even if I think we'll have double the sales. We don't have the labor. We don't have the capital. We don't have the infrastructure.

We should be trying to understand: Will people's preferences change forever? Or if farmers expand, will they be sorry in two months when everything opens back up, because consumers will just go back to what they were doing before?

Do you see a silver lining?

The silver lining is that consumers are reaching out to local farmers. We're in a moment many of us have dreamed about — where farmers become the center of our communities again, instead of how they've been perceived in Vermont, for the most part, like this ecological nightmare.

So I think it's changing the way people view the agricultural landscape, and that's really positive, because people need to understand that we need farmers.

It's just too bad it took a pandemic to get people to turn around and go to their local farmer for food.

'The Beckoning Country'

When Danby native Oliver Olsen came home to Vermont in 2003, he brought his job with him. Ever since, the 44-year-old Londonderry resident has worked remotely, now as director of professional services for Workday, a cloud-based financial management and human resources company.

So, when the pandemic forced many professionals out of the office in March, Olsen's life didn't change much. "For those of us who have been doing this for two decades, it's nothing new," he said.

Olsen, a former state representative, has expressed concerns that virus-fleeing second-home owners could overwhelm local health care systems in ski resort communities such as his own. But he also sees an opportunity to address Vermont's demographic challenges by convincing them to stay.

Already, according to Olsen, some people who ordinarily run multinational companies from downtown Manhattan are doing so from Vermont. "They're not battling a one-hour commute through traffic or crowded subway systems with people sneezing in their face," he said.

"I think one of the takeaways from this pandemic is that, while population density affords many benefits in a highly populated world, it also presents some very challenging public health risks," Olsen continued. "So there's gonna be some really interesting opportunities as people rethink their living arrangements."

How can we capitalize on that?

I think what's going to be really helpful is making clear that not only can you work remotely, but you can work remotely from Vermont — not just Westchester County, N.Y. To the extent we can tell those stories, I think that will help sort of paint this picture of Vermont as Vermont Life did back in the '60s, as "the beckoning country."

Do you see any drawbacks to that sort of urban flight?

If this were to take shape, we're still gonna have the same challenges we always have — namely, we have a workforce shortage in a lot of supporting industries, if you will, so we'll start running into capacity issues.

We're gonna need more plumbers and electricians. We don't have enough today.

What are your biggest long-term fears?

We could end up in a situation where, on the one hand, we have an opportunity to market Vermont as this wonderful place to come to if you want to get out of an urban area. But if we have village centers and downtown areas where three-quarters of the resorts and shops are shuttered because they couldn't survive the cash-flow crisis they're facing right now, that's a difficult package to sell.

'Wellspring'

Alex Crothers spends most of his day "talking about what the new normal is going to look like" in the music industry. "It's the same conversation over and over," he said. "It feels like you're in [the movie] Groundhog Day because nobody has any answers."

The 44-year-old founder and co-owner of South Burlington's Higher Ground music club recognizes and accepts that his business will be among the last allowed to reopen. "We're in the business of mass gathering," he said. "We bring people together. It's the basis of everything we do."

Even after such gatherings are permitted again, it's not like Crothers will be able to flip a switch and welcome a major musician back onstage. The nationally touring acts his company books for events, such as Ben & Jerry's Concerts on the Green at Shelburne Museum, "have really long lead times setting up their tours, announcing them, putting tickets on sale," said Crothers, who lives in Burlington. And few bands will bother rebooking tours until most of the country reopens. "So COVID has created a disruption in that cycle that, depending on how long it lasts, it's at least a six- or eight-month disruption," he said.

How can people more safely gather in the post-COVID era?

We've been doing a livestreaming show every night since we decided to close the club. It's been incredibly cathartic, but it's not a business model, just something to have fun.

We're talking about whether there's a way to bring people together drive-in-movie-style, where people stay in the car.

How will the industry change because of this?

It's gonna have a dramatic effect. Independent music venues are small businesses, and small businesses are going to take it in the teeth. So there's going to be a constriction, and that's going to be tough.

I think we're also going to see an incredible wellspring of creative talent. We've just shut artists in their houses for seven weeks. Artists have to keep creating, and we've just given them space where they have very little distraction because there hasn't been much to do.

What kind of government support are you seeking?

Certainly, dollars in the bank are gonna help. From a local or state level, if they can't provide dollars, they can provide some type of tax relief, whether it's abatement of the sales tax or the rooms and meals tax. Those types of things will help provide a runway to get us back up and running.

There could also be some regulatory things, like allowing us to hand a can of beer to a customer and watch them open it. It's a very small thing, but technically right now it's against the law.

'Tough Place to Make a Go of It'

A rural life survey conducted last summer for Vermont Public Radio and Vermont PBS found that 40 percent of those polled could not afford an unexpected $1,000 expense. Nearly half said they would advise an 18-year-old to leave the state to build a successful life or career.

"It's been a pretty tough place to make a go of it," said Vermont Community Foundation president and CEO Dan Smith, whose organization underwrote the survey. "Prior to this pandemic, our biggest underlying challenges were, frankly, demographics and workforce. I think related to both of those was sort of the sense of economic malaise that was in place."

The 45-year-old Burlington resident, who previously ran Vermont Technical College, is particularly concerned about the fate of that institution and the rest of the Vermont State Colleges System. "There is no publicly articulated strategy for higher education across all the public entities that exist," he said. "To me, it was the legislature's responsibility to articulate that strategy and to fund it."

What keeps you up at night?

The knowledge that in Vermont — and, frankly, I think nationally — the pandemic didn't land on an economy and civil society that was particularly healthy. We were deeply divided based on the lived experience of people in different regions and states and economic standings and races and ethnicities in ways we all knew were not civilly or socially sustainable.

What keeps me awake is that we'll somehow miss the chance to build a much stronger and more resilient economic environment.

Are there some institutions that should be allowed to fail?

I think, regardless of how hard we work in this next 18-month window, there are going to be institutions and enterprises that don't survive. The key is to recognize that it's not necessarily because of the pandemic that they won't survive. In a lot of cases, it's because of underlying trends, underlying demographics or an underlying lack of strategy that might have informed different decisions by public or private funders.

How do you think the nonprofit world is going to fare in this crisis?

People's response in this moment around philanthropy and giving has been incredibly inspiring. You take away from that that Vermonters of all stripes are really committed to the health and well-being of their neighbors in a crisis.

I'm worried, though, that the pandemic will accelerate existing trends, like the decline in giving that has played out over the past decade. I think that's going to put an incredible amount of pressure on the nonprofit community and, at some level, the state, because it relies on the nonprofit community to provide so many core services.

A Second Chance

Even before the coronavirus hit Vermont, Aly Richards and her spouse had a hard enough time finding affordable childcare for their 17-month-old twin boys. Like many Vermonters, they relied on family to ease the burden — in their case, Richards' parents and grandmother, who live in Newbury.

Now, the 34-year-old Montpelier resident and her brood spend half their time quarantining in Newbury, where Richards takes part in Zoom meetings from her childhood bedroom and the older generations help look after the twins.

"I don't know how other people are doing it," she said.

As CEO of Let's Grow Kids, a nonprofit focused on increasing access to early childhood education, Richards spends her days trying to help families facing similar challenges.

For now, she says, Vermont is doing better than most states because it has chosen to bail out the childcare industry, providing "stabilization" grants of 50 to 100 percent of private tuition. But the transition back to a fully functioning system — which Gov. Scott announced last week would begin June 1 — could be perilous, with small class sizes straining programs.

One bright spot? The importance of Let's Grow Kids' mission is now abundantly clear. "We're hopeful that, after witnessing the true impacts of life without childcare, we can really come together to strengthen the system," Richards said.

Do you expect a lot of programs to close?

Across the country, yes. In Vermont, I think fewer.

If you could recommend one policy change post-pandemic to strengthen childcare, what would it be?

I would say wage supplements to early educators.

People are going to be dusting themselves off and asking, "What do I do with myself in this economy?" It would really change things if being an early childhood educator was a really viable profession that allows you to put food on the table.

What are your biggest fears?

My biggest fear is missing the opportunity that's ahead of us.

People say, "If we were starting from scratch, we would've done it differently." Well, we have that chance.

'We've Had Enough'

Early studies have found that, nationally, people of color have been infected with and killed by COVID-19 at disproportionate rates. Researchers suspect that health and economic disparities are to blame.

In Vermont, the Department of Health didn't even collect data on the race and ethnicity of coronavirus patients until civil rights groups spoke out. "In a way, it serves as validation that the work we do matters because, left to their own devices, the majority won't pay attention to the minority," said Tabitha Moore, state director of the NAACP.

Moore, a 42-year-old Wallingford resident, said that, anecdotally, Vermonters of color appear to be suffering more from the outbreak. "For example, I think about our migrant communities, who are incredibly fearful because our president is shutting down avenues of support for immigrants and migrants," she said. "There's a saying that when the U.S. sneezes, people of color get the flu."

What can leaders in Vermont do to address these racial disparities?

Policy makers need to recognize that it is the marginalized people who are the litmus test for whether or not what they're doing is working. So it's smarter for them to include marginalized populations from the get-go, because how well you do is based on how well your most disenfranchised people are faring.

What opportunities can we find in this crisis?

My hope is that the people who have been kind of beaten down the most — the essential workers who've been barely making enough working 40 hours a week — that they say, "We've had enough," and that those of us who are salaried support them. Because they're the ones keeping us going: the migrant workers who are doing all the jobs that we wouldn't do even when there wasn't a crisis. That they're getting their due.

'Command and Control'

What does Rob Roper think of the power that state government has exercised during the coronavirus outbreak?

"It sucks, and you can put that quote in there," he said. "It's a command and control economy."

Roper, president of the conservative Ethan Allen Institute and a former chair of the Vermont Republican Party, has long sought a more limited government. The 51-year-old Stowe resident sees the pandemic-induced economic crisis as confirmation of his worst fears.

"It's been devastating," he said. "This is shattering the foundation of what was already a crumbling economic foundation to begin with."

What can we do about it?

This is where my optimism is: It's forcing our state government to figure out how to reform a system that was in desperate need of reform, but there was no political will to do it. So I think it's an opportunity for a reset. This response really calls for a much more free-market approach.

To be clear, do you think the state should not have imposed the restrictions it did?

I don't have a medical background, and I'm not going to play doctor and say you shouldn't have done this. I pray to God they made the right decision, but I won't question it.

Are there institutions we must save? Ones we can let go of?

If you have a shrinking tax base and larger obligations, something's gotta give. I would hope we can find a more streamlined way to deliver K-12 education, given all the online learning going on.

I think a lot of the stuff we've been spending on, like electric vehicle subsidies and charging stations, are probably not going to be a top priority for a lot of Vermonters when we get to the end of this.

What's your biggest fear?

You're gonna get a lot of special interest groups that say, "We're too big to fail" or "Our issue is too important," and they're gonna put a lot of pressure on legislators to raise taxes to fill those buckets. And the attempt to do so is going to really send us into a tailspin.

Court-Zoom

When Marilyn Skoglund retired from the Vermont Supreme Court last year, she was hoping to take up bartending. But with her local watering holes mostly dry, the 73-year-old juris emerita has instead been "putzing around" her Montpelier home, where a daughter and son-in-law have sought refuge from Boston.

"Oddly enough, it's hard to tell there's anything different in my life. I isolate a lot. I'm home sewing masks for my friends," she said. "And, meanwhile, I'm practicing making my son-in-law and myself a vodka tonic."

This pandemic has prompted some major short-term changes to the judiciary in Vermont. What long-term changes do you foresee?

I think being forced into using the videoconferencing modality to do more video arraignments will keep diminishing the amount of sheriffs' time transporting defendants and allowing for greater reassurance that it does work that way and it's not harming anybody's due process rights.

Other than that, I don't see the judiciary changing much at all.

Do you think it should?

You're still going to need jurors to test the witness on the stand. Zoom is never going to replace live testimony.

What's your biggest fear coming out of this?

What I fear is that we're going to become more and more angry with one another and more and more hateful. I think there will be more protests and viciousness. It's going to get worse before it gets better and people come together.

Pants Down'

Vermont's medical providers have acquitted themselves well during the coronavirus crisis, according to Dr. Harry Chen, but the pandemic has exposed glaring failures in the broader health care system.

Case in point: the dearth of personal protective equipment at hospitals around the country as the outbreak raged. "We've tried to make health care so lean and just-in-time," said Chen, a former state health commissioner and emergency room doctor who lives in Burlington. "We got caught with our pants down, so to speak, because we couldn't get it just-in-time when everyone else was trying to get it just-in-time."

Chen, 67, hopes industry leaders learn from their mistakes and fix what's broken, including a fee-for-service revenue model that has left hospitals in dire financial straits because they haven't been able to perform moneymaking procedures.

His biggest fear? "That we'll just go right back to the way things were," Chen said, "and that we won't take time to digest what we've been through and what needs to be different."

Do you think this will accelerate the trend of consolidation in the health care system or arrest it?

I think that needs to be part of the discussion. On the one hand, on a regular, everyday basis in Vermont, we probably have more hospital capacity than we need. At the same time, we probably didn't have enough capacity for a crisis like this. So we have to be careful.

What opportunities are there for post-pandemic Vermont?

The whole concept of going to work sick is totally different now. It should be. Frankly, I'm as guilty as anyone. You get sick and you go to work, and you plow through it just because that was your job. But now it's part of the collective responsibility to not go to work sick.

At the same time, we have to create the conditions — that's what public health does — in which people can take time off without losing their jobs, much less their incomes.

What keeps you up at night?

I worry about the effects of all this on mental health, whether it be anxiety or the physical contact we're trying to avoid.

In medicine, we talk a lot about therapeutic touching — sitting down next to a patient and laying down your hands. In the COVID era, now we do it through an impermeable divider with an iPad. So we have to figure out how to get back to some of that — obviously, in a measured pace — because that's part of the human connection we all need.

A Darwinian Disease

Alan Newman doesn't expect Vermont to be back in business anytime soon.

"I know our idiot president is trying to open the economy to win the election, but I think that's going to backfire," he said. "I'm not a fan of Phil Scott. I find him overly conservative. But at times like this, conservative isn't a bad strategy, and I think he's made the right moves."

Newman, a 73-year-old Burlington resident, knows a thing or two about how businesses work. He helped create three of Vermont's most enduring brands: Seventh Generation, Gardener's Supply and Magic Hat Brewing.

"It's going to be a slow opening," he predicted. "Regardless of what politicians say, I think consumers are going to be the ones who drive the speed at which we open up, and I think they're wary."

If you were starting a business post-pandemic, what would you be looking at?

Something with very low overhead so that, going forward, it could remain as flexible as possible.

Do you think people's buying patterns will change in the long term because of this?

You know Buckminster Fuller? He had this line I heard 25 or 30 years ago that stuck with me, and I found it to be true, always. They asked him how he could predict the future. He said, "Well, I don't. There are patterns, and I just follow them." One of the patterns he talked about was bigger, bigger, bigger, bigger, smaller. Everything starts to grow, and at some point it reaches maximum size and it explodes into a bunch of small pieces again.

I think we're now seeing the retraction of the big-box stores and a return to the small specialty stores. And I think we're seeing more and more people moving online.

What have we learned?

The pandemic has really demonstrated a number of things. No. 1, it's demonstrated we really are a global society. This concept that we're small, little nations unto ourselves, that's just garbage.

From a purely practical standpoint, I think what we've learned is, we've gotta deliver reasonably rapid internet to rural areas.

What needs to change?

What the pandemic has done economically is, it's — medically, economically, I think any way you look at it — it's been Darwinian. It's attacked the weakest. Some weeding is going on.

While we've been talking about online education for years, and while I've seen a million pitches for a better online education system, what the pandemic is doing is, it's driving an upgrade to the education system. The same thing for medical. Why is it we need to go into a doctor's office for 80 percent of our health needs?

So I think that, long term, there could be some real positives coming out of this, whether it be wiping out the unhealthiest costs of the medical system or whether it's wiping out the unhealthiest costs of the educational system.

Inn Distress

Near the top of Liz Bankowski's list of things to worry about is the fate of Vermont's smallest towns.

"We tend to see things through the lens of Chittenden County," the 72-year-old Brattleboro resident said. "The rest of Vermont isn't that way."

Bankowski, who served as chief of staff to former governor Madeleine Kunin, was president and CEO of the Windham Foundation until last month. The nonprofit's mission is to preserve the rustic character of the tiny town of Grafton. It also operates Grafton Village Cheese and the Grafton Inn.

When the pandemic struck, Bankowski said, "It felt like I was looking into an abyss. You are almost paralyzed. How do you even begin to think about what happens after this? Then you say to yourself, You only need to get through this day, this week, this month."

The foundation's businesses are surviving — for now. But Bankowski wonders when the state's tourism economy will rebound and the Grafton Inn will again be fully booked.

"We really rely on weddings and gatherings and board meetings. That's our economic engine. It's not clear that they're coming back anytime this year," she said. "If it's a long time before we can hold those events, we will not survive."

How long do you think it will be before people feel comfortable traveling to Vermont?

Anecdotally, you get the feeling that people want to get out of their cities, and they want to come to Vermont. We're relatively small entities in Vermont. We don't need hundreds of people. We just need the loyal ones to come back.

The question is, how long until we can start renting rooms again?

How is Brattleboro faring?

Every time I drive up Main Street, I wonder what won't be there. All those signs that say "closed" — how many of them will remain up?

The margins are thin. The coffee shop and the sandwich shop and the food store — their margins are thin, and they've had no income now for a number of months, so I think they're all in peril.

Any reasons for optimism?

If we have to live through this, I think we're all feeling, Well, I'm glad we lived through it here.

Stress Test

As executive director of the Vermont Sustainable Jobs Fund, Ellen Kahler has spent years challenging people to think more deeply about the state's food and energy systems. Now, the coronavirus crisis is forcing just such a conversation.

"I think it presents an opportunity to rethink what we really want out of a restart," said Kahler, 53, of Starksboro.

How do you think the coronavirus will change Vermont in the long term?

The mid- and longer-term opportunity that we've been presented with through this pandemic related to our economy is to refocus on shortening supply chains for essential products that we all use every day, like food. That also includes things like energy sources — for instance, wood chips, wood pellets, firewood, solar and community-scale wind. You're keeping those most important components of what we need every day produced more locally and keeping those dollars circulating in our economy.

When you have longer supply chains, it actually makes us more vulnerable.

How do we address that?

We need to be investing in increasing our processing capacity and warehousing and distribution. It's not enough to just produce it. You have to move it. You have to store it. In some cases, you're freezing it or lightly processing it.

This pandemic is kind of a test case of our capacity. How do you think our food systems are faring?

After [Tropical Storm] Irene, we had communities cut off for weeks, but we found ways to get food supplies into those communities.

We have not until now been tested with longer-term, wider-spread emergencies, which could happen with back-to-back hurricanes coming up the East Coast, for instance, or massive rain events that wipe out entire crops in the state. And those things can still happen.

There has not been an emergency feeding plan for this kind of widespread lack of food so many Vermonters are experiencing right now with this particular type of pandemic.

Squandered Capital

Vermonters have never embraced change, according to FreshTracks Capital cofounder Cairn Cross. "There's this general, collective interest in things remaining the same — and the 'same' being pegged to, I don't know, the 1940s," he said.

But the coronavirus crisis will force the state to adapt, the 61-year-old Ferrisburgh resident believes, and to address systemic challenges.

"You know that saying where, by the fourth generation, all the wealth is gone?" Cross said. "That's like Vermont. We're a couple generations from the 1940s or whatever [was] the high-water mark of what we think Vermont should be, and we've squandered our resources. But yet we've wanted to keep up appearances, so we've continued to underfund the pensions and the state colleges. We've done all these things and kept going rather than making those really difficult choices."

What exactly needs to change?

What we really need at the leadership level is to all agree on 20 big problems the state faces, and then we get rational and say, "We can't solve 15 of these, but here are five we can solve."

The other stuff we will simply let go.

Community Resilience

Social distancing doesn't come naturally to Monique Priestley. The 34-year-old web developer has spent years trying to bring neighbors together in her Upper Valley town of Bradford. Central to that effort has been the Space on Main, the coworking venue she founded two years ago in a shuttered five-and-dime store.

"Community is what we've really needed," she said. "That piece of it is still important — maybe more important right now."

With the Space on Main mostly closed to comply with Vermont's stay-at-home order, Priestley has been finding other ways to connect. A new group she helps lead, Bradford Resilience, is engaged in what she calls "grassroots emergency response." Volunteers have been picking up groceries and prescriptions for their neighbors, writing thank-you notes to first responders, sewing masks, and even gathering trash around town.

Priestley said she doesn't know what the future holds for the Space on Main, but she hopes that community members will stay engaged once the pandemic passes.

How do you think it will affect small towns like Bradford?

For the last decade, volunteerism has been dying. But as soon as we put out a request saying, "Your neighbor needs your help," 86 people signed up. I'm hoping people will keep paying more attention to their neighbors and the needs of their communities.

What opportunities do you see for rural Vermont?

Vermont has so many small businesses, entrepreneurs in the woods. And each town, because of this, has been trying to create business directories to support them. I've heard over and over, "I had no idea we had that many businesses in town." So I think there's a huge opportunity to be a little more aware of the people in your community.

'Sad Stories'

Two months ago, chef-owner Eric Warnstedt and his business partner, Will McNeil, employed 170 people at their four restaurants: Hen of the Wood locations in Waterbury and Burlington, Prohibition Pig in Waterbury, and Doc Ponds in Stowe. Now, just two employees remain on the payroll. They help the owners handle takeout nights, which rotate among the restaurants.

"It's crazy," said Warnstedt, 44, of Waterbury Center.

The restaurant group applied for and received funding through the federal Paycheck Protection Program. But the low-interest loans are forgivable only for businesses that hire back most of their employees — an impractical solution for restaurants that must remain closed. So Warnstedt is desperately hoping for government assistance better tailored to the industry. Without it, he warns, many restaurants will reopen, but most of those could close again within months.

"We think we're going to see some really sad stories come up," he said.

In your ideal world, what kind of support would the state provide?

We really need six to eight months of some fixed-cost coverage just to keep the doors open, the lights on, to get through this.

If a restaurant is open for a month, and it's only allowed to seat outdoors with six-feet spacing for tables, there's literally no way that you can pay rent, pay your staff. So, if we are going to take this phased approach [to reopening the economy], which we support, there's no way to do it and be financially viable.

How can restaurants safely operate in the coming months?

Corona's not going away. This is something we're going to live with for a long time. As individuals, we need to take into account what level of risk we're comfortable with. And, for me as a restaurant owner, I would like for the doors to be open and for signage to say things like, "Please be respectful of everyone's space. Here are all the things we're doing to make as clean an environment as possible."

How will your business change when it does reopen?

We'll probably have more limited offerings. We're going to really refocus on our farmer relations, our brewer relations. If we used to have 24 taps and 12 were from Vermont, when we reopen we'll have 12, and all 12 will be from Vermont.

Is that for philosophical or practical reasons?

It's a combination. It gets us back to why we're doing this. And if we're only gonna do a third of the business, there's no need for as many options.

We can make it worth your while without 24 beer options.

Do you see any silver lining?

I can't say I really do. I do think this period of time has been beneficial for a lot of us if we can get out of our own heads and reconnect with our homes, our families. But the overwhelming fear of my business failing, my friends' businesses failing, sort of overrides the goodness.

So do I see a silver lining from corona? I don't think I do.

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

About The Author

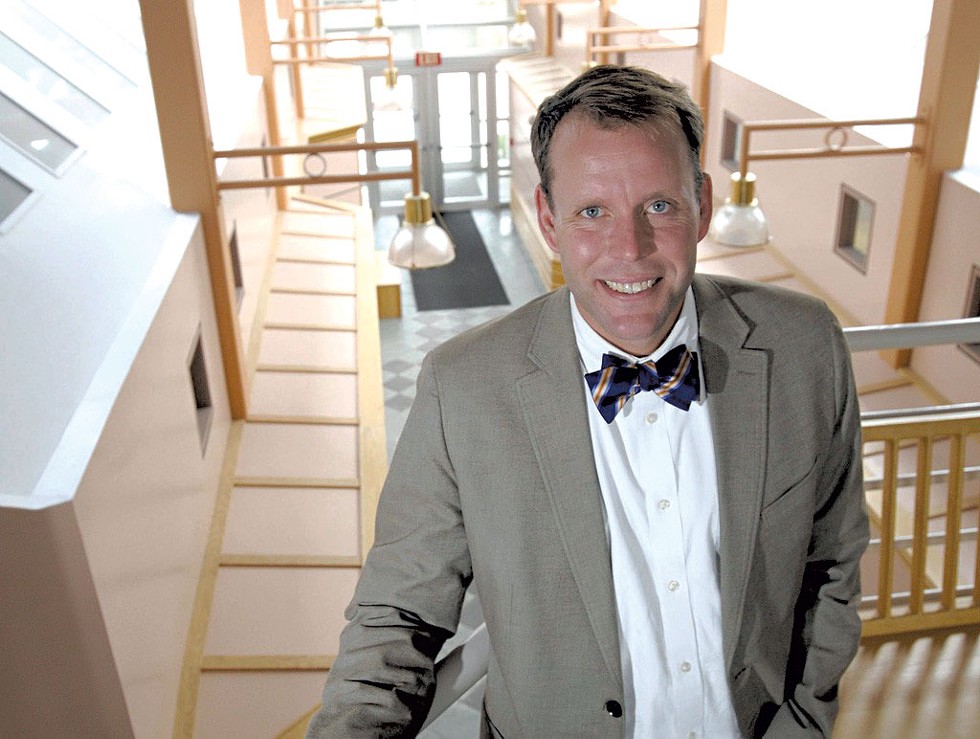

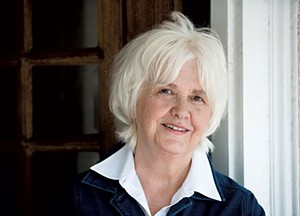

Paul Heintz

Bio:

Paul Heintz was part of the Seven Days news team from 2012 to 2020. He served as political editor and wrote the "Fair Game" political column before becoming a staff writer.

Paul Heintz was part of the Seven Days news team from 2012 to 2020. He served as political editor and wrote the "Fair Game" political column before becoming a staff writer.

More By This Author

Latest in Business

Speaking of...

-

ArtsRiot in Burlington Reopens With Pizza and a Bar

Mar 29, 2024 -

Emergency Eats Provides Restaurant Meals to Flood-Impacted Vermonters

Aug 10, 2023 -

Waterbury’s Hen of the Wood Draws Fresh Energy From Its New Home

Jul 11, 2023 -

A New Book Celebrates 25 Years of Higher Ground Concert Posters

Mar 29, 2023 -

ArtsRiot to Host Location of PlantPub, a Massachusetts Vegan Restaurant

Mar 23, 2023 - More »

find, follow, fan us: