Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

Before Burlington's Proposed Mall Makeover, They Called It 'Urban Renewal'

Published May 25, 2016 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated May 30, 2017 at 8:26 p.m.

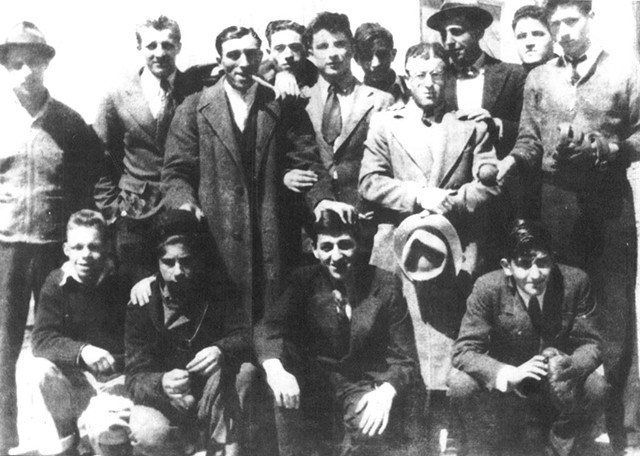

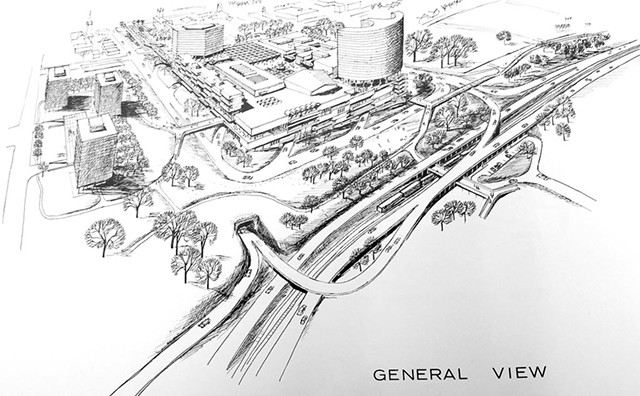

click to enlarge

- Courtesy

- A 1964 Horizon document envisioning the urban renewal zone and elevated highways along the lake

The tower of cardboard boxes spoke for itself at the May 2 meeting of the Burlington City Council. While activist Jay Vos testified against a $220 million makeover of the city's downtown mall, his crude model illustrated how 14 stories — the height of proposed residential and office complexes that are part of the project — would look in comparison to the Queen City's standard three. Mall owner and developer Don Sinex, a partner in Manhattan-based Devonwood Investors, is seeking a zoning variance to construct what would be the tallest building in Vermont.

Despite myriad criticisms of his plan to redo the Burlington Town Center — that it's out of proportion, houses too many college students, caters to the rich, casts a big shadow — no one has come to the defense of the existing mall, which decidedly isn't working. One Burlington planner likens it to a crypt. And it's not just the empty storefronts and dated décor. "We have this fortress that consumes the center of our downtown," Burlington City Councilor Joan Shannon said by way of explaining her vote to advance the Sinex project. "It's worth something to me to open that up."

Urban planning is supposed to survive the test of time, but it doesn't always. Five decades ago, Burlington's politicians and city officials thought it was a great idea to have a windowless suburban-style mall extending three blocks west from Church Street, cutting off north-south travel on Pine and St. Paul streets.

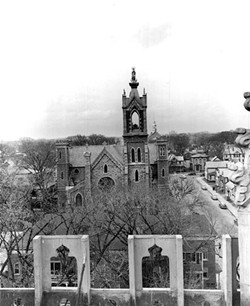

An even bigger "urban renewal project" had paved the way for the shopping mall a decade earlier, when some of the same developers — plus Burlington voters — opted to level a 27-acre portion of downtown. For a century or so, a working-class neighborhood had occupied the area between Battery and South Champlain streets, where the Hilton, St. Paul's Cathedral, the Costello Courthouse and Cathedral Square now stand.

Architects Bill Truex and Tom Cullins and business owner Pat Robins helped envision the redevelopment, which initially included two 16-story apartment buildings that were never constructed. During the 1960s and '70s, the urban renewal zone got filled in haphazardly, project by project. The stretch of Cherry Street between Church and Battery has only recently begun to attract pedestrian-friendly businesses such as Hotel Vermont and Hen of the Wood.

Despite his plan to fundamentally alter what was built 40 years ago between the Marketplace and now-vanished Pine Street, Sinex says he views his envisioned redevelopment as "phase two" of what Truex, Cullins and Robins "put there." The new downtown centerpiece would represent an updating of the ideas that animated urban renewal around the middle of the 20th century, he suggests.

Fifty years from now, will the Sinex intervention be viewed as an ingenious improvement or a crushing disappointment?

Arrivederci, Burlington

In 1963, Burlington voters approved a $790,000 municipal bond in support of what was officially known as the Champlain Street Urban Renewal Project. Along with a $2.4 million federal grant, the city's sum financed a plan to raze and radically redevelop the neighborhood now referred to as Burlington's Little Italy. The bond item received overwhelming support — except in Little Italy. The project destroyed 300 buildings; 157 households were displaced.

The ethnically diverse enclave had been designated as "blighted" by proponents of the prevailing approach to urban revitalization. "Remember," says Frank Cain, Burlington's mayor from 1965 to 1971, "there were no minimum housing standards in those days. Many of the homes were dilapidated. It was dangerous. A lot of people there used kerosene, and I always worried about a strong wind on a cold night causing a conflagration."

Demolition got under way in 1966. Two years later, the neighborhood was just a memory.

"That wasn't a period in our history when we wanted to preserve old buildings in need of repair," says Julie Campoli, a Burlington-based specialist in urban design. "The norm then was to wipe the slate clean and build something bigger. There was a tendency to think in terms of diagrams and abstractions. Separation of shopping, office and residential districts looked good in diagrams."

This urban-renewal ethos was put into practice in cities around the country. It's now widely regarded as antithetical to what makes urban life attractive to 21st-century sensibilities: walkable, colorful streets with a compact mixture of housing, workplaces, restaurants, shops and entertainment venues. But the urban-renewal theorists of half a century ago considered themselves enlightened visionaries. In Burlington, at least, there was nothing nefarious about the thinking that led to the makeover of the center city.

Cullins, a retired Burlington architect involved in the Champlain Street plan, says its framers were motivated by "a utopian dream of revitalizing and rebuilding a city." They sought to defend Burlington from the existential threat posed by a metastasizing suburbia. Church Street was already losing stores in the 1950s to Williston and Shelburne roads in South Burlington, where land was cheap and parking plentiful, notes Truex, a retired partner of Cullins' in the architecture practice that still bears both men's names.

In order to compete with the 'burbs, city planners thought they had to provide comparable amenities, easing access for automobiles and segregating retail outlets and business offices from residential areas, as is the typical mode of development in the swathes that ring American cities.

"What you see downtown today was everyone's best guess at the time of what should be done to save the city," Sinex comments.

Driving Forces

A consortium of local developers and networkers called Horizon got the contract to redevelop Burlington's urban-renewal zone. Some of the elements in its plan would be considered progressive even by today's standards. That's because its architects — from the Burlington firm of Barr, Linde and Hubbard — included Cullins, Truex and one other product of Harvard's Graduate School of Design. The school imparted some of the principles that came to be associated with Jane Jacobs, an outspoken urbanist who helped rescue neighborhoods in Manhattan and Toronto from destruction disguised as progress.

For example, Horizon wanted to fashion a strong pedestrian link between downtown Burlington and Lake Champlain, which it characterized as an incomparably valuable but underappreciated asset. Because "commerce got the upper hand" on the downtown lakefront in the 19th century, Burlington's focal point had shifted inland, with retail stores and grand homes being built well away from Champlain's shore, Horizon recounted in a pamphlet it published in 1964. The aim of reconnecting the city with the lake thus "represents a return to tradition," the developers argued.

Horizon cited concerns half a century ago that are still relevant today. In addition to calling attention to their local roots, the urban renewers observed that, "People leave Vermont or decide against coming here for lack of opportunity." They cast the Champlain Street plan as a source of temporary and ongoing jobs for Burlingtonians as well as a beacon to tourists and a sophisticated come-hither gesture toward flatlanders who might be induced to relocate to the city. Urban renewal would likewise "help discourage further flight to the suburbs of existing commercial enterprises," the prospectus predicted.

Ironically, these goals were to be achieved by transposing onto downtown Burlington many elements of the suburban-design template. A "covered parking area" — a large garage equipped with a gas station and car wash — was listed as the first feature in Horizon's plan. "There is no doubt that the creation of the proposed covered parking facilities with fluid pedestrian-free access to all roads in Burlington will revitalize the city core," the developers wrote.

That reference to "pedestrian-free access" alludes to the contemporaneous but separate plan to build an elevated multilane highway along the downtown waterfront. This envisioned "Beltline" was intended to connect with the interstate highway to the south and to another "pedestrian-free" road to the north, which was actually built in part and is now designated Route 127. A cloverleaf interchange for entry to and exit from downtown Burlington was to be constructed at what's now Main Street Landing.

Local opposition, combined with the toxin-laced Pine Street Barge Canal, scotched that plan. The Beltline couldn't run through what was later declared a Superfund site.

The governing notion of the Horizon scheme was to close the urban-renewal zone to cars — except for parking — and to speed them into and out of downtown. That was the reasoning that led to blocking off South Champlain Street between Pearl and College.

Horizon's plan stated that "the automobile should be treated as an honored guest." But as a countervailing indication of the developers' foresightedness, the plan added that cars "must not be allowed to usurp the privilege of man to enjoy in safety and pleasure the fruits of urban culture." Horizon also called for resuscitating "moribund railroad passenger service in Vermont," suggesting that a link to Montréal could be activated in time for trains to run to and from its 1967 World's Fair.

Best-Laid Plans

Some of the structures Horizon envisioned for the urban renewal area did come to be: The Radisson Hotel that opened in 1971 is now a Hilton; in the 1980s, Burlington got its long-awaited department store — Porteous, now Macy's — on Cherry Street. A 14-story office building became two shorter structures — the five-floor People's United Bank on Pine Street and the eight-story building at 100 Bank Street that now houses the Burlington Free Press.

What didn't get built? A pair of 16-story residential towers proposed for the southeast corner of Cherry and Battery streets — on the Courtyard Marriott site — that were supposed to be designed by the firm of über-modernist architect Mies van der Rohe; a 3,000-seat auditorium; a proposed pair of cinemas; and a recreation center, dubbed the City Club, with squash courts, a swimming pool, bowling lanes, a curling rink and virtual links known as the Golf-a-Tron.

Horizon never managed to obtain the financing needed to turn its grand visions into reality. The original developers did build the Costello Courthouse, but responsibility for carrying out the rest of the urban renewal project passed to Cousins Properties, an Atlanta-based development company that built the People's United building, as well as the office complex with mirrored exterior windows on the same block at Pine and College. Cousins' involvement in Burlington proved short-lived, however. A plane carrying three members of its executive team plunged into Lake Champlain soon after takeoff on a snowy night in January 1971. Neither the aircraft nor the remains of its passengers and crew have ever been recovered.

That trauma prompted Cousins bosses to abandon the Burlington project. Contracts for the urban-renewal initiative were awarded in 1972 to Mondev, a Montréal-based real estate company that went on to build much of what now stands in place of Little Italy.

The same year that the Cousins plane went down, a fire consumed St. Paul's Episcopal Cathedral on Bank Street between Pine and St. Paul streets. The city subsequently traded a lot it owned in the urban renewal zone on the corner of Battery and Pearl streets for the cathedral's former site. That exchange enabled an Episcopal cathedral to rise anew in the distinctive concrete form designed by Cullins. The swap also cleared the way for construction of Burlington Square Mall in 1974.

The two-level shopping center was conceived as a means of adding retail square footage, as well as a Cherry Street parking garage, that would allow Church Street to compete more effectively with suburban malls, recalls Robins. At the time, he served as president of a downtown merchants' association and as chair of Burlington's street commission. Along with Truex, then the head of the planning commission and chief of the city's urban-renewal agency, Robins viewed Burlington Square Mall as an essential link that would unite Church Street with the revitalization zone west of Pine Street and with Lake Champlain. The overarching idea, Robins says, was to shift the city's main retail artery from a north-south to an east-west orientation. "I thought that was very strategic," Robins adds.

The Church Street Marketplace, remade as a pedestrian-only passage in 1981, is also an extension of concepts reflected in the urban renewal plan, he adds.

Like Robins, Cain, now 93, believes Burlington benefited from urban renewal. "I think it was a very successful metamorphosis of a small city," the former mayor says.

Robins joins critics of the project, however, in lamenting the closing of Pine and St. Paul streets to make way for the mall and the office buildings constructed on Bank Street. "We should have found a way to preserve at least pedestrian and bike access" on those north-south routes, he says in retrospect.

Robins also agrees with those who revile the stretch of Cherry Street between Church and Battery as ugly and unwelcoming. The Burlington Square Mall project installed a horizontal, windowless slab and a now-rusting garage along the south side of Cherry, which is lined with institutional buildings and parking lots on its north side.

Sinex is proposing a total makeover of the mall, breaking it into smallish retail shops that would have entrances on Cherry Street as well as along reopened Pine and St. Paul streets. The developer vows, "We're going to take the suburban mall out of downtown."

'Real Deal'

click to enlarge

- Courtesy Of Burlington Town Center

- Rendering of the northeast aerial view of the proposed construction

The block of Pine Street north of College that dead-ends at the mall's parking garage — at 100 Bank — couldn't be more different from the corridor of creativity it becomes in the South End. Truex predicts that some of the suburban-inspired architecture here won't last much longer. He says the first commercial office building erected in the urban renewal zone — the low-rise office building with mirrored windows at the northwest corner of Pine and College — should be first to go. The nearby People's United Bank building will also eventually fall to the wrecking ball, according to Truex. For a building set in the urban core, he says, it's sited too far back from the street.

The eight-story building at 100 Bank Street will also have to come down or be radically altered in order to accommodate the plan to reopen Pine Street. Restoring it and St. Paul Street through downtown is an "extremely difficult" undertaking, urban planner Campoli says, noting that only a few U.S. "superblocks" built in the '60s and '70s have been subsequently dismantled.

Few Americans wanted to live in urban cores when retail-and-office superblocks were being plopped into cities, Sinex notes. "But there's big demand for that now," he adds. "Lots of people want to live in the heart of cities." Sinex intends to construct 250 units of housing — and 300,000 square feet of office space — as part of his $220 million redesign of the downtown mall.

Truex, Cullins and Robins are all in favor of the 14-story residential towers that would be set back from Church Street to prevent shadows from darkening the Marketplace. The idea of more urban dwellers shopping downtown certainly appeals to Burlington restaurateurs and other business owners.

Contemporary urban designers such as Campoli do wonder whether the retail component of Sinex's plan will prove viable in the long term. Online shopping is revolutionizing the consumer experience, she notes. Campoli asks: "Who knows what that will mean five or 10 years from now?"

Sinex says he's factoring such uncertainties into his plan. "It's not going to be about stuff you can buy online but the sort of things people need to get in person on an everyday basis," he explains, citing a supermarket as one example of the sort of retail he envisions adding downtown.

As the Horizon group presciently proposed more than 50 years ago: "The bazaar rather than the suburban shopping center will be the character sought. The pedestrian rather than the automobile will be king."

Macy's may or may not be part of the redesigned mall, Sinex adds. The department store's owners "aren't particularly pleased" about reopening St. Paul Street, which would interrupt the flow of customers from the eastern part of the complex. "They're more of a suburban-style enterprise," Sinex says of Macy's. "They're not a good downtown department store." He adds that he hopes Macy's stays but says he'd be interested in buying the space if the store decides to pull out of Burlington.

Of course, Sinex has to first clear several hurdles — even with the preapproval agreement the Burlington City Council granted on May 2. His financing is not yet in place. Sinex said lenders want to see a "real deal" — that is, a fully permitted project — before signing on, but he remains optimistic that it will happen. Truex is also confident, noting that "this is a small project by Devonwood's standards." The people of Burlington will also have a say when they vote in November on whether to approve $21.8 million in tax-increment financing to pay for public infrastructure improvements associated with the plan.

Sinex acknowledges musing about how his project will be judged in 2050 and beyond. He suspects it will be regarded as a positive and progressive alteration of the urban fabric.

Burlingtonians may, 30 or 40 years hence, want even more of what Devonwood Investors aims to put in place within the next five years, Sinex speculates. The 925-car parking garage that he wants to build downtown will be designed, he notes, to allow for relatively easy conversion into apartments.

Spin aside, it's hard to imagine how the Sinex redevelopment will actually be assessed by future generations. Horizon's principals were no doubt constrained by the same limits of the imagination when they put forward an urban-renewal plan in 1964 that today still receives as much damnation as praise.

End of the 14-Story?

click to enlarge

- Courtesy Of Burlington Town Center

- Rendering of the new Church Street entrance to the mall

Four thousand fliers appeared on Burlington doorsteps this past week to rally opponents of the 14-story towers that would be part of the Burlington Town Center makeover. The developer has asked for a zoning change to raise the city's building height limit from 105 feet to 160.

"If this zoning change occurs, not only will this massive mall be possible, a dangerous precedent will be set and other oversized developments will follow suit," warns the flier, published by the Coalition for a Livable City. The new group includes residents who attempted to preserve land at Burlington College and some whose protests helped stop zoning changes that they saw as a threat to affordable artist space in the South End. Save Open Space Burlington, the South End Alliance and other groups joined forces.

"Basically we don't believe that developers should dictate the zoning and planning regulations of the city," said Genese Grill, a Burlington artist, writer and leader of the coalition.

Forty people, many of them new volunteers, distributed fliers door-to-door. "I'm getting enormous response by people who are outraged and want to do something," said Grill, who lives in the Old North End.

The flier and a Stop the 14-Story Mall page on Facebook urged citizens to converge Tuesday night at a Burlington Planning Commission meeting about the project.

In response, supporters issued their own "get out the troops" email blast. The Burlington Business Association urged members to attend the meeting and write to commission members in favor of the project. The BBA and other supporters say the $200 million-plus project is desperately needed to revitalize the aging mall and reclaim downtown streets that were blocked by the building decades ago.

Don Sinex, who owns the mall, said the design of the buildings will not be "massive" and they will fit in with the Burlington skyline. Said Sinex: "We will continue working to turn a 40-year-old monstrosity that does not serve the community into something that will."

The original print version of this article was headlined "Up Against the Mall"

Related Stories

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

More By This Author

About The Author

Kevin J. Kelley

Bio:

Kevin J. Kelley is a contributing writer for Seven Days, Vermont Business Magazine and the daily Nation of Kenya.

Kevin J. Kelley is a contributing writer for Seven Days, Vermont Business Magazine and the daily Nation of Kenya.

About the Artist

Matthew Thorsen

Bio:

Matthew Thorsen was a photographer for Seven Days 1995-2018. Read all about his life and work here.

Matthew Thorsen was a photographer for Seven Days 1995-2018. Read all about his life and work here.

Speaking of...

-

Burlington Budget Deficit Balloons to $13.1 Million

Apr 25, 2024 -

The Café HOT. in Burlington Adds Late-Night Menu

Apr 23, 2024 -

Burlington Mayor Emma Mulvaney-Stanak’s First Term Starts With Major Staffing and Spending Decisions

Apr 17, 2024 -

Totally Transfixed: A Rare Eclipse on a Bluebird Day Dazzled Crowds in Northern Vermont

Apr 10, 2024 -

Middlebury’s Haymaker Bun to Open Second Location in Burlington’s Soda Plant

Apr 9, 2024 - More »

Comments (6)

Showing 1-6 of 6

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.

- 1. UVM, Middlebury College Students Set Up Encampments to Protest War in Gaza News

- 2. Dog Hiking Challenge Pushes Humans to Explore Vermont With Their Pups True 802

- 3. Scott Official Pushes Back on Former State Board of Ed Chair's Testimony Education

- 4. A Former MMA Fighter Runs a Wildlife Rehabilitation Center in Cabot News

- 5. Burlington Budget Deficit Balloons to $13.1 Million News

- 6. Senate Committee Votes 3-2 to Recommend Saunders as Education Secretary Education

- 7. Home Is Where the Target Is: Suburban SoBu Builds a Downtown Neighborhood Real Estate

- 1. Totally Transfixed: A Rare Eclipse on a Bluebird Day Dazzled Crowds in Northern Vermont 2024 Solar Eclipse

- 2. Zoie Saunders, Gov. Scott’s Pick for Education Secretary, Faces Questions About Her Qualifications Education

- 3. Don't Trash Those Solar Eclipse Glasses! Groups Collect Them to Be Reused 2024 Solar Eclipse

- 4. State Will Build Secure Juvenile Treatment Center in Vergennes News

- 5. Vermont Awarded $62 Million in Federal Solar Incentives News

- 6. Queen of the City: Mulvaney-Stanak Sworn In as Burlington Mayor News

- 7. New Jersey Earthquake Is Felt in Vermont News