Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Business

Cannabis Company Could Lose License for Using…

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

Black Staff Say Burlington Nursing Home Failed to Protect Them From Abuse

Published October 21, 2020 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated November 10, 2020 at 4:12 p.m.

Employees of one of Vermont's largest nursing homes, Elderwood at Burlington, say they have faced repeated racial attacks, both verbal and physical, on the job. Managers, they say, have ignored their complaints and failed to protect them from a particularly hostile and violent patient.

"I have never experienced the type of racism that I am experiencing at Elderwood at Burlington," said one registered nurse, who is Black. "We're told at Elderwood that residents have the right to say what they want to say. They have a right to call us 'niggers.' They have a right to degrade us. And they have a right to threaten physical harm."

The nurse is one of five employees who described Elderwood, formerly known as Starr Farm Nursing Center, as a toxic workplace with little regard for its majority Black workforce; two former employees shared similar experiences. They declined to be identified, citing fears of professional retribution.

Seven Days obtained patient records corroborating their accounts and demonstrating that staff had repeatedly alerted their supervisors to the abuse they faced. According to legal experts, Elderwood could be in violation of state and federal civil rights laws if it was aware of the alleged racial harassment and failed to protect its employees.

Five of those who spoke with Seven Days are travel nurses who come to Vermont for weeks or months at a time to fill key health care positions — a particularly acute need as the coronavirus pandemic continues to overwhelm long-term-care facilities. Though all five hail from the South and have worked throughout the country, they say they have never encountered such working conditions.

"As long as I've been living, I have never been subjected to that type of racism," said a second current employee, who is Black. "Growing up in Mississippi I didn't experience this."

One former employee, who has traveled to Vermont for work four times, said she chose not to renew her contract with Elderwood in September because she could no longer tolerate the abuse.

"It's very degrading. It's very dehumanizing. It makes you feel powerless and helpless. I'll never allow myself to be in that type of situation for that long again," said the former employee, who is also Black. "I can tell you that this experience completely changed my view of Burlington and Vermont forever. Forever."

The 150-bed New North End facility was known as Starr Farm until January 2019, when it was acquired by Elderwood — a regional nursing home chain owned by New York City-based Post Acute Partners. Administrators at the Burlington facility did not respond to multiple interview requests, but a corporate spokesperson said in a written statement that managers had been "working to address the concerns expressed by our staff and they take those concerns very seriously."

The spokesperson, Charles Hayes, added, "Elderwood does not tolerate harassment of any kind and prides itself on promoting a culture of diversity and inclusion."

According to the employees, that's not the case. They described racist encounters with several patients but said that one 83-year-old white man in particular has tormented them since he moved into the facility in March. Not only have managers tolerated his behavior, the employees said, they have failed to tell him it's wrong.

Instead, according to a third current employee, supervisors "let him know they're glad he's part of Elderwood. They're never telling him it's not OK." The employee, who is Black, said, "I know you can't change him as an individual because that's in him, but you can be part of the solution, not the problem."

The resident's records, some of which were obtained by Seven Days, document a series of troubling events that took place over at least a four-month period.

In June, according to one entry, he punched a Black male nurse in the chest "while calling him racial names." After consulting with an on-call supervisor and a facility doctor, the staff sent the resident to the University of Vermont Medical Center for a psychological evaluation. As soon as he returned, the records show, he continued to physically assault and chase staff members around Elderwood's rehabilitation unit, telling them to "go back to Africa."

"Resident continues with inappropriate behaviors as well as racial slurs at the colored staff, calling them coons and no good fat asses, myself included," a nurse wrote. Around the same time, the resident blocked an entrance to the facility's dining hall and told patients and staff that he would "knock their lights out." When a nurse attempted to intervene, she wrote, he "started ramming into my legs with his walkers, saying, 'hows that feel?'"

In one August episode, according to the records, the resident attacked a nurse after she attempted to prevent him from running into another resident with his wheelchair. "If it's one thing I can't stand it's a nigger," he said, according to the nurse's notes, repeating the word 10 to 15 times. "He then physically threatened me and ran over my right foot with his wheelchair and attempted to strike me. When other staff attempted to redirect him, he shouted, 'Don't touch me; all you want to do is help the nigger.'"

According to a fourth current employee, who witnessed the event, "I've never heard the N-word so many times." That employee, who is white, said in an interview, "In the moment, I was surprised that no one was stepping in. I couldn't believe there was no response pattern in place."

Days later, according to the second current employee, an assistant administrator called a meeting with nurses and supervisors to discuss the incident. "She said that the resident had the right to say those things," the employee told Seven Days. "I'm not upset because this man did this. What upset me is that Elderwood failed to protect me and the other people of color. They failed to protect us."

After the meeting, the resident's behavior continued to escalate. In September, according to a nurse's note included in his records, he prevented a staff member from exiting a dayroom and said, "I would kill all the niggers if [I] had a gun." When told that he did not have access to a firearm, the resident said, "I will find something else." The note made clear that several supervisors, including the corporate liaison and director of nursing, had been notified of the event.

According to the resident's records, his many diagnoses include "unspecified dementia with behavioral disturbance." Several of the staff members expressed skepticism that the condition was responsible for his conduct, arguing that he appeared cognizant of his past actions. They said management's only response was to require more training on dementia.

Hayes, the corporate spokesperson, said he could not address the situation in detail, citing privacy laws. But he said in a second written statement that the facility's clinical staff "began working with the resident as soon as concerns were raised to try and address negative behaviors and comments."

"[T]hose efforts may not have been adequately communicated back to the affected staff," Hayes continued. "[H]owever as we were able, we reassigned any staff member who made a request if they felt uncomfortable working with the resident." He added that the facility had provided additional training "to help staff develop and strengthen communication skills with residents who suffer with cognitive impairments."

Regardless of the resident's diagnosis, legal experts say, Elderwood has a duty to protect its staff from abuse.

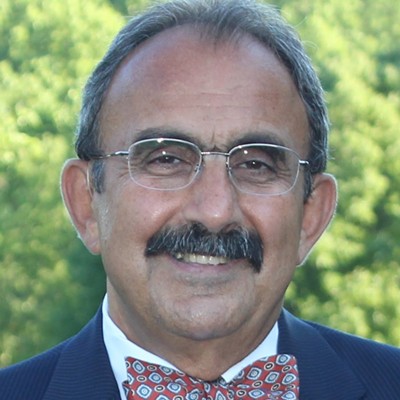

"Under both Vermont law and federal law, employers are responsible for the actions of nonemployees who harass their employees, where they know about the harassment and they fail to take immediate and appropriate action to stop the harassment," said Julio Thompson, director of the civil rights unit of the Vermont Attorney General's Office.

Thompson's staff and the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission are charged with investigating civil rights complaints and taking enforcement action. Citing confidentiality rules, Thompson could not say whether the Attorney General's Office had received complaints about Elderwood.

The situation is not without precedent in Vermont. In 2018, the state's Human Rights Commission found that the Department of Mental Health had failed to protect Black employees from racial harassment perpetrated by colleagues and patients at the state's psychiatric hospital. In a settlement agreement with the commission, the state agreed to improve its policies and conduct more training; a separate settlement between the plaintiff and the state was not made public.

Bor Yang, the attorney who investigated the case and is now the executive director of the Human Rights Commission, said that an employer is no less responsible for an employee's welfare just because the perpetrator has a psychiatric disability.

"If someone comes into a store and starts using the N-word against an employee, what do you do?" added Robert Appel, a civil rights attorney who represented the plaintiff in the psychiatric hospital case. "You say, 'You're not welcome here.'"

According to Sean Londergan, the state's long-term-care ombudsman, nursing home patients are not in any way entitled to voice hateful remarks. He said the facility would be within its rights to ask the resident to leave if it could not otherwise solve the problem. "The resident doesn't have some right to say whatever they want and the staff just has to suck it up," Londergan said.

Monica Hutt, commissioner of the Department of Disabilities, Aging and Independent Living, said she found the allegations against Elderwood "horrifying," though she said her department only has jurisdiction over the health and safety of residents — not staff.

She said she was particularly concerned that the alleged victims are travel nurses, given Vermont's reliance on out-of-state help to staff long-term-care facilities during the pandemic. "They're just like gold right now," she said. "I'm really distressed that anyone would come to Vermont and feel unwelcome."

Several of the Elderwood employees said they were unlikely to return to Vermont, and two said they had warned the agencies that placed them in the facility about the conditions they encountered.

"We come here and leave our families hundreds of miles away," the second current employee said. "We come in to help a facility. We get treated the worst. As long as we're in the building covering all their [double shifts], we're good. But anytime something goes wrong, we're the first to be blamed. And they don't care at all about one of us. They don't care."

The first employee said that, when she arrived in Burlington two months ago, she was heartened to see Black Lives Matter activists occupying Battery Park.

"On my way to work I would pass by the protest, and I thought, This is really cool to see," she said. "And then I get to this facility and see that, no, Black lives don't matter."

The original print version of this article was headlined "Resident Racist | Black staff say Burlington nursing home failed to protect them from abuse"

Related Stories

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

Tags: Health Care

More By This Author

About The Author

Paul Heintz

Bio:

Paul Heintz was part of the Seven Days news team from 2012 to 2020. He served as political editor and wrote the "Fair Game" political column before becoming a staff writer.

Paul Heintz was part of the Seven Days news team from 2012 to 2020. He served as political editor and wrote the "Fair Game" political column before becoming a staff writer.

Speaking of...

-

19th-Century Educator Alexander Twilight Broke Racial Barriers, but Only Long After His Death. It’s Complicated.

Sep 20, 2023 -

Black High School Athletes Speak Out About Racism in Vermont Sports

Feb 1, 2023 -

Feds Sue Burlington Nursing Home, Claiming Racial Abuse of Black Staff

Sep 6, 2022 -

Ridding Vermont of Restrictive Covenants Is Proving Complicated

Apr 27, 2022 -

'The Fleming Reimagined' Reflects the UVM Museum's Ongoing Reckonings

Oct 13, 2021 - More »

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.

- 1. Cannabis Company Could Lose License for Using Banned Pesticide Business

- 2. Pro-Palestinian Encampment at UVM Has Disbanded After 10 Days Education

- 3. Driven by Grief and the Hope of Helping Others, Chip Piper Aims to Run 10 Marathons in 10 Days Opioids

- 4. New Marker Provides a Window Into the History of Burlington's Battery Park True 802

- 5. Older Vermonters Who Have Given Up Driving Can Face Isolation, Loneliness This Old State

- 6. Barre Voters Will Choose Between Thom Lauzon and Samn Stockwell for Mayor Politics

- 7. Renewable Energy Bill Heads to Governor's Desk News

- 1. Totally Transfixed: A Rare Eclipse on a Bluebird Day Dazzled Crowds in Northern Vermont 2024 Solar Eclipse

- 2. Zoie Saunders, Gov. Scott’s Pick for Education Secretary, Faces Questions About Her Qualifications Education

- 3. Aggressive Behavior, Increased Drug Use at Burlington's Downtown Library Prompt Calls for Help City

- 4. 'We're Leaving': Winooski's Bargain Real Estate Attracted a Diverse Group of Residents for Years. Now They're Being Squeezed Out. Housing Crisis

- 5. State Will Build Secure Juvenile Treatment Center in Vergennes News

- 6. Vermont Awarded $62 Million in Federal Solar Incentives News

- 7. Barre to Sell Two Parking Lots for $1 to Housing Developer Housing Crisis