Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

Coping With Death and Grief in the Time of Pandemic

Published April 29, 2020 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated May 3, 2020 at 9:51 p.m.

Marguerite Meunier's brother, Roger Guillemette, died of COVID-19 at Birchwood Terrace Rehab and Healthcare in Burlington on April 14. He was 68. A few hours before he passed away, Marguerite said her last words to him over the phone — that she loved him, that he had been a good brother, that he wasn't alone. He was silent, but the nurse who propped the phone against his ear told Marguerite that he seemed to be listening.

Marguerite's mother, Cecile Guillemette, still lives on the dairy farm in Shelburne where she raised her seven children, two of whom she had buried before Roger. Marguerite, the eldest, lives nearby; her other siblings all settled within 20 miles of the homestead. Their family has always been an inseparable unit, pragmatic and spontaneous in their displays of affection. Before the days of social distancing, they would drop by each other's houses unannounced for coffee or to borrow each other's trucks for random hauling jobs.

The morning after Roger died, Marguerite went to the farm to tell her mother the news. They sat in her kitchen and cried, six feet apart and unable to hug one another. "My mother is 98 years old," said Marguerite. "I didn't want it to be the last hug."

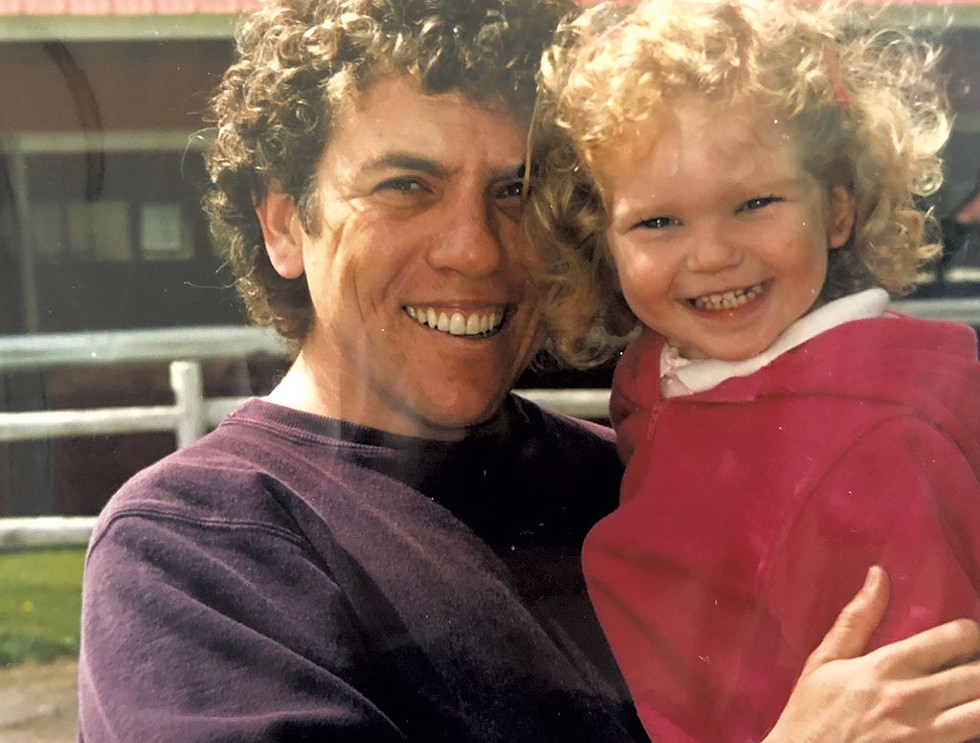

Roger worked for 32 years as a custodian at Frederick H. Tuttle Middle School in South Burlington, but the farm was the center of his universe.* "He loved farming. He loved being around machinery, being around animals, around family," Marguerite said.

Remembering Vermonters Lost to COVID-19

Since the novel coronavirus was first detected in Vermont on March 7, more than 860 people have been diagnosed with COVID-19, according to the state Department of Health. Of those, at least 47 have died. Each left behind family and friends. Each had a story.

Roger, who had diabetes, had prearranged his memorial service in 2016 and selected his plot at Resurrection Park, a Catholic cemetery behind St. John Vianney Church in South Burlington. He had wanted a large gathering for his family, which spans five generations. But his funeral, held in the cemetery on the cold, overcast morning of April 16 — "a typical funeral day, where it's just bleak," as Marguerite put it — was limited to 10 people. Marguerite and her siblings made sure Cecile was warm and comfortable in her folding chair at Roger's graveside, and then everyone kept their distance.

Since the burial, Marguerite has immersed herself in the business of settling her brother's affairs, but in the midst of a pandemic, even the most mundane acts of closure are fraught with difficulty. Recently, she spent an entire afternoon trying to disconnect Roger's cellphone number, to no avail. The Verizon store in South Burlington is closed to walk-in customers, and she couldn't get a human being on the line to help her through the process.

"It's so strange," said Marguerite. "It's like it's not finished, like he's not gone."

'A death unlike any other death'

As of press time, 47 people in Vermont have died of COVID-19, well below the fatality rate of the worst-case-scenario projections. But in this moment, a death for any reason presents its own set of unprecedented complications. One of the pandemic's cruelest ironies is that it has marooned people in illness and grief, separating loved ones when they most need one another's physical presence.

Across the state and the country, visits to hospitals and nursing homes have been banned or severely restricted. Memorial services have been postponed indefinitely, replaced by burials at which no more than 10 people can be present, and only then while standing six feet apart. Making funeral arrangements has become a touchless transaction, which poses a significant challenge for older generations.

"We're doing almost everything by phone and email, and, for the most part, we're dealing with a generation that's used to coming in and making arrangements in person," said Michele Ready Ambrosino, director of Ready Funeral & Cremation Services in Burlington, with whom Roger planned his memorial. "Some of them don't have access to email."

In hospitals and nursing facilities where patients are being treated for the coronavirus, death has become a strangely cloistered event, sometimes witnessed only by one or two caregivers who are cloaked in protective gear.

That kind of abrupt, unseen loss can have profound psychological consequences for the bereaved, according to Francesca Arnoldy, program director of the University of Vermont Larner College of Medicine's end-of-life doula certification program. Like birth doulas, who provide emotional and tactical support during pregnancy, end-of-life doulas help the dying and their families ease into the spiritual and physical reality of death.

"Often, when there's an impending loss, people can incrementally integrate what's happening," said Arnoldy. "And now, there's this chasm. When the loss occurs and the loved one hasn't been able to watch the decline, see the last breath, say their goodbyes, it can be really surreal, and there can be significant shock and guilt for not being able to care for the person. You just want to know that someone was there to sit vigil, and that's something that's missing for a lot of people right now."

Before the pandemic, hospice chaplains could enter homes and hospital rooms and hold the hands of the dying and their loved ones. Now, said Joan Newton O'Gorman, a chaplain in the UVM Health Network's Home Health & Hospice division, she can only comfort them over the phone. "People are asking me, 'Am I dying alone?' And I don't have any antidote to that," she said. "The only thing I can do is affirm what they're feeling — to say, 'This is a death unlike any other death.'"

Recently, O'Gorman said, she got a call from a woman caring for her dying mother at home. The woman put her on speaker and placed the phone on her mother's bed. For the next few minutes, O'Gorman sat on the line in silence, listening to their sobs.

The virtual goodbyes, when they're even possible, feel surreal, incomprehensible. A week and a half ago, Jody Albright saw her brother, Stephen, for the last time on Zoom. Stephen, 70, was dying of COVID-19 at Birchwood Terrace; the nursing home had made an exception to its embargo on visitors for patients in their final hours, but Jody, who is undergoing treatment for cancer, didn't feel safe entering a nursing home where 49 people had tested positive for the coronavirus.

Her other two brothers, both of whom are in their late sixties, were concerned about their own health. And the prospect of sheathing themselves in protective gear to sit at their brother's bedside seemed darkly absurd, almost comical. "I was picturing hazmat suits, Ghostbusters," said Jody. "Stephen wouldn't even have been able to see our faces."

Instead, one of Stephen's caregivers at Birchwood set him up on a Zoom call with his family on a Saturday afternoon. Jody said he was barely awake but cheerful; for no apparent reason, he wore a pair of sunglasses on his forehead, a tiny glimmer of the provocatively dressed musician he once was.

Stephen and Jody had been in a rock band together in the '80s, and she sang a song to him that she'd found on one of their old practice tapes. He mouthed the lyrics along with her. Then he told her that she should visit him, that he'd take his walker into the hallway to meet her. Jody, not knowing what else to say, promised him that she would try.

Stephen died the next morning. Jody doesn't know if anyone was with him at the end.

'Only the good die young'

A recent New York Times investigation found that nearly 10,000 COVID-19 deaths in the U.S. — one-fifth of the country's fatalities — have been connected to long-term-care facilities. The pandemic has exacted a disproportionate toll on elderly residents of nursing homes, who may already have few surviving family members or friends to care for them.

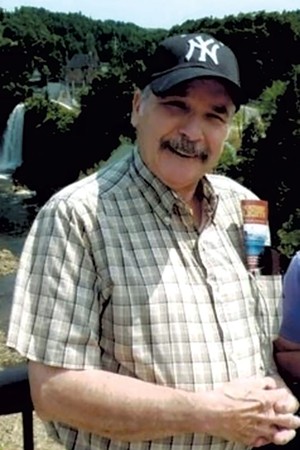

To date, 10 deaths have occurred at Burlington Health & Rehabilitation Center, the nursing home that became the first epicenter of the outbreak in Vermont. One of the facility's early casualties was 80-year-old Bob Poulin, who moved there in December 2019 after a period of declining health. His wife, Barbara, had died in 2012, and he had no children.

Related Race to Contain: A Nursing Home Is the Epicenter of Vermont's Coronavirus Outbreak

Race to Contain: A Nursing Home Is the Epicenter of Vermont's Coronavirus Outbreak

By Derek Brouwer

Coronavirus

A few months before he was admitted to the nursing home, Bob granted power of attorney to his friend of more than a decade, Peter Lavallee, a retired South Burlington police lieutenant whom he'd met through his Knights of Columbus council in Milton.

The two were an odd couple. Peter, 15 years Bob's junior, is an indefatigable archivist of life's paperwork, meticulous in both his speech and his recall of dates; Bob, who ran a roofing and siding business, had a habit of stretching the truth and blurting out whatever was on his mind, for which Peter would gently reproach him. "I used to tell him, 'Bob, only the good die young,'" Peter recalled. "'That's why you're still alive.'"

They were both born on July 12, which Peter discovered when he went to visit Bob's wife's grave at Resurrection Park in South Burlington. Next to her burial plot, he saw Bob's future headstone, chiseled with his date of birth. From then on, Peter sent him cards that said, "It's Your Birthday!" with the Y in "Your" crossed out.

In the early years of their friendship, Bob lived in an apartment in Holy Cross Senior Housing in Colchester. He was blind in one eye and had trouble driving, so Peter often chauffeured him to Essex Junction to run his errands. Their excursions usually began with a trip to the all-you-can-eat Grand Buffet on Pearl Street, followed by a stop for groceries at Mac's Market, where Peter knew by heart Bob's route through the aisles.

"He was kind of a different guy, so people didn't always think he was very friendly," Peter said. "And, in a lot of ways, he wasn't. But I got along with him."

Bob wasn't close to his extended family, and he often told Peter how lucky he was to have met him. They often discussed Bob's end-of-life wishes. According to Peter, Bob had no interest in being placed on life support; not long before moving into Burlington Health & Rehab, he had purchased a funeral policy with A.W. Rich Funeral Home in Essex Junction that included cremation, a Catholic service and burial in the plot next to his wife.

The two friends saw each other for the last time on March 2. A week and a half later, Peter got a call from Burlington Health & Rehab that Bob had fallen while trying to get out of bed and that his overall health was deteriorating. When Peter called his friend to check on him, he hardly recognized his voice.

"I had to verify that it was actually Bob," he said. "It didn't sound like him. He sounded weak, different." It was the last time they spoke.

The nursing home announced its first case of COVID-19 on March 16. Three days later, Bob tested positive for the coronavirus. The following day, Peter received another call from his nurse, who asked Peter to confirm Bob's instructions not to be placed on life support. He said that his friend didn't want to be kept alive.

Peter talked to his priest, Father John Feltz at St. Ann Catholic Church in Milton, about whether a pastor should perform last rites for his friend. Given the escalation of the outbreak at the nursing home, Peter decided he didn't want to jeopardize the health of a clergy member; to date, more than 100 priests have died in Italy, one of the hardest-hit countries in the coronavirus pandemic.

Bob died two days later, on March 22. Peter wanted to see his body at the funeral home, but they wouldn't allow him inside. A few days later, when he went to pick up Bob's ashes, Peter had to sign for the urn on the funeral home's front porch.

On April 6, there was a small memorial service at Resurrection Park. Eight people attended, including Peter, his wife and some of Bob's fellow Knights of Columbus members. They stood scattered around his grave in a 50-foot radius. Bob had been a member of the Vermont Air National Guard, but no honor guard could be present to perform taps; the funeral home played a recorded version from a speaker. A Catholic priest offered short prayers.

Bob's final moments rack Peter. "I fear that Bob was probably alone, without any staff members being there to accompany him, console him or attend to him in those final hours, or to pray for him," he said. "I will never know if anyone was there for him."

'There's no sense of closure'

With the majority of the country under stay-at-home orders, virtual memorial services have become the new normal. Many of these take place on Zoom; the videoconferencing app has become the default platform for a spectrum of human encounters, from staff meetings to funerals, with no atmospheric differentiation.

Judy Alexander watched her mother's funeral on Zoom. The ceremony, restricted to 10 people, was held at a cemetery in Lindenhurst, N.Y., on a rainy afternoon in early April. Judy, tuning in from the desk of her home office in South Burlington, could barely make out the rabbi's words over the rankling whoosh of wind against her nephew's iPhone, from which he was streaming the memorial service to her and 20 or so others who had joined the call. Some of the virtual participants had forgotten to mute themselves; occasionally, an unseen dog barked.

Leila Alexander passed away on April 1 at a nursing home on Long Island. She was 88 and had some physical and cognitive problems, but Judy said her death hadn't seemed imminent. That morning, Judy's sister had a routine conference call with Leila's care team; a few hours later, Leila went to sleep and never woke up. Judy had planned to visit her mother in March, but the widespread lockdown of nursing and eldercare facilities made that impossible. The last words Judy said to her mother, over FaceTime on March 27, were "I love you."

A Jewish burial is a participatory ceremony: The family and friends of the deceased take turns heaping mounds of dirt on the casket, a gesture of finality and devotion. But because a communal digging implement could become a vector of the coronavirus, the funeral home requested that the family bring their own shovel, which they used to pile on a few symbolic clods. Afterward, Judy's sister dropped the shovel into the grave, a memento for Leila from her pandemic funeral.

For Judy, not being physically present at the burial has created a bizarre skip in her reality. "It feels like we don't even know for sure whether it's Mom in there," Judy said in mid-April, two weeks after the funeral. "It's like I'm in this fourth dimension, where she could pop up at any moment. There's no sense of closure."

When the service ended, nobody could hug. The handful of people who had attended in real life went home to their computers, and everyone convened on Zoom again later that day. Mostly, Judy said, they talked about how much Leila would have hated the whole thing.

"My mother wanted certain poems, a march from Verdi's Nabucco," Judy explained. Leila had also wanted Judy to sing a psalm, but, given the circumstances — and the notorious unreliability of Zoom's audio — her performance was scuttled.

Leila herself loved to sing, much to her children's torment. "She was a terrible singer, just terrible, and she loved to make up stupid songs," said Judy. When Judy and her siblings were growing up on Long Island, Leila would take them on walks to the beach and lead them in a dirge-like chorus: "Marching, marching, Mommy's children are marching." Leila had wanted to have her grandchildren sing their own version, substituting "Nanny" for "Mommy," as they escorted her casket to the cemetery. That wasn't possible, either.

"The whole thing was kind of awful," Judy reflected. The virtual shiva that followed, she said, was also less than satisfying. Under normal circumstances, shiva is a seven-day period of mourning that commences after the funeral, in which family and friends congregate in the home of the deceased, eating and reminiscing. Shiva is a time of intense togetherness, designed to ensure that the bereaved are never alone in the delicate early stages of mourning.

"When you have shiva, people are constantly coming in, telling stories — it's a very cathartic process," Judy said. "We couldn't have that this time. Nobody could even bring food."

At a time of compulsory social isolation, Zoom can offer a much-needed glimpse of loved ones' faces. But the virtual format also strips the occasion of its essential shiva-ness — the deeply physical camaraderie of grief.

"Because we can't get together in the way that we usually do, I think that the process of grief is becoming elongated," said Rabbi Amy Small, who leads Ohavi Zedek Synagogue on North Prospect Street in Burlington, where Judy attends services.

Small believes that the mourning practices of Judaism are its most psychologically astute contributions to the world: "It's about enabling grief to flow, not saying, 'You're done, move on,'" she said.

Small has been organizing daily prayer sessions on Zoom so that Judy can say the kaddish, a prayer of mourning, in the presence of a quorum of 10 Jewish adults, called a minyan. In accordance with Jewish custom, Judy will say the kaddish once a day for the next 11 months.

"This has all been an incredibly surreal experience, a very lonely experience," she said. Lately, she's been reading articles about the strangeness of adapting Jewish mourning traditions to a world transformed by a pandemic, which brings her some indescribable feeling of validation.

"'Comfort' isn't the word for it, I don't think," Judy mused. "I'm not sure what the word is, really. My mother would know."

'What am I leaving them with?'

Marc Kamhi knew he was going to leave the world in the middle of a pandemic. At 62, he had been living with two types of cancer for several years. In early April, he moved into the McClure Miller Respite House in Colchester, an inpatient hospice facility for people with six months or fewer to live. On a recent Saturday morning in mid-April, Marc said he felt like he was on a boat, pitching at sea.

"You think you've grabbed on to a handrail, and then you get the news that your cancer has gotten worse, and then it's not just the boat rocking all over, it's you — your pain, your capabilities, everything else that's happening in the world right now," he said. "And there's so much to be sad about, but I feel like this really isn't the time to be abandoning the planet, you know? I just want to get out there and fight that sadness, not sit in here like, 'Gee, sorry, I'm not feeling well!'"

That day was his son's 23rd birthday, but Marc couldn't see him in person. In the midst of the coronavirus crisis, visitors are a strictly regulated luxury, even for the terminally ill. Respite House residents are allowed two designated guests; Marc chose his wife and his 26-year-old daughter, Joanna, who had been more involved in his treatment. Every time Joanna entered the building, she had to fill out a symptom questionnaire and undergo a temperature screening.

Joanna was two months away from graduating from law school at the University of Pennsylvania when her father's condition took a turn for the worse. She booked a one-way rental car from Philadelphia; once Marc was admitted to the Respite House, she began spending most nights on the pullout couch in his room. She recorded their conversations on her phone so that her future children would be able to hear his voice.

That Saturday, Marc was worried about what the world would look like for his family in the next few months — whether the stock market would implode and plunge them into financial turmoil, how they would be able to support each other in their grief when they can't physically be together.

"The whole funeral thing is really hard for me," he said. "Who knows what will be allowed, what won't be allowed? What am I leaving them with?" Marc wanted a Zoom memorial service, he explained, something unadorned and practical.

"My dad is a really humble person," said Joanna. "I don't think he wanted to be an inconvenience or mess up anyone's plans. He's always thinking about how to make life easier for people."

In the early 2000s, Marc worked on the luggage ramp at United Airlines at Burlington International Airport, and he got into the habit of waving to the planes as they taxied away from the gate. He loved watching passengers wave back at him, framed by their tiny oval windows.

"Those people are about to go 32,000 feet in the air, where they have no business being," Marc said. "That moment of connection is so important for humanity. It's not a casual farewell. You've got to send them off properly."

One week later, on Saturday, April 24, Marc passed away. Joanna was with him at his bedside; his son said goodbye from the other side of his window.

* Correction May 3, 2020: An earlier version of this article misstated Roger Guillemette's relationship history. He was married, then divorced. He was unmarried at the time of his death.

Remembering Vermonters Lost to COVID-19

Since the novel coronavirus was first detected in Vermont on March 7, more than 860 people have been diagnosed with COVID-19, according to the state Department of Health. Of those, at least 47 have died.

Among Vermont's coronavirus victims thus far are a roofer, a musician, a general store owner, a psychologist, a switchboard operator, two custodians, two truck drivers and a pair of brothers who groomed ski trails at Mount Snow.

All but three were 60 or older, and all but five were white. At least 27 lived in Chittenden County, and at least 24 were residents of two Burlington long-term-care facilities: Birchwood Terrace Rehab and Healthcare, and Burlington Health & Rehabilitation Center.

Each left behind family and friends. Each had a story. Here are four of them.

Robert Francis Burdo Sr.: 'He lived life to the fullest'

April 4, 1942-March 30, 2020

Steve Richer and Bob Burdo became friends when the two were barely 5 years old, living around the corner from one another in Burlington's Old North End. Richer recalls Bob helping him string wire from his home to a neighbor's house to construct a makeshift telephone line. "We had a lot of fun," he said. "And we've remained friends for all of these years. I guess you would say we were more brothers than friends."According to Richer, who was exactly six months older than Bob, the two never failed to call one another on their birthdays — until this year. Bob, who had been recovering from an illness at Burlington Health & Rehab, contracted the coronavirus and died on March 30, five days shy of his 78th birthday.

Bob was born in Burlington in 1942, the oldest son in a family of six boys and girls. His father, Francis, worked long hours at the Burlington Fire Department, so Bob often cared for his younger siblings. "He was like a second dad," recalled the youngest brother, Steve, who is 14 years his junior.

After graduating from high school, Bob joined the Air Force. Eventually he returned to Burlington and worked for a time at Farrell Distributing, delivering beer to restaurants and stores. "I knew him as Bob the truck driver," Steve recalled. "He was a tough guy. He didn't complain."

Bob had four children: the late Robert Jr. and Dawn with his first wife, Mary Ranck; and Tina and Eric with his second wife, Valerie Wilford.

"He was the best dad ever," Dawn said. "He liked getting together with the family, cookouts. He liked having fun with all of us."

Bob eventually became a custodian at Burlington's Integrated Arts Academy, then known as the H.O. Wheeler School, and worked there for nearly 25 years. For much of that time, Dawn worked down the hall in the school's cafeteria. When her shift ended, he would just be showing up, and the two would spend time in his office. "We would just talk — about my life, his life, the kids," Dawn said.

"Bob was a very hard worker, a very honest person," said Herb Chamberlain, who was the head custodian at H.O. Wheeler. "You could always count on Bob to have your back."

You could also count on him to needle the school's Red Sox fans. "There was no other team for him except the Yankees," Chamberlain said.

Even after he retired, Bob would return to H.O. Wheeler to bring the custodians pizza. "He'd sit down and have a little talk with us," Chamberlain recalled. "He wasn't very rich, but he lived life to the fullest."

According to Dawn, her father was "old-fashioned and set in his ways." Said Richer, "He had his opinions, and he was the type of guy who stuck to whatever he thought." But, according to his youngest brother, Bob did have the capacity to change.

"He was raised in a time when a lot of people wouldn't say, 'I love you.' And as he got older, and as he probably got to feel his softer side, he learned to say that," said Steve, who lives in California. "And he did."

Steve spoke with his brother one last time days before Bob died at Burlington Health & Rehab. "I said, 'Hey, Bob, I understand you came down with the coronavirus.' He says to me, 'You know what, Steve, if you want some, come out and visit me,'" Steve recalled. "It's amazing he had that sense of humor up to the time he was passing away."

— Paul Heintz

Franklin Delano Bray: 'He was a very strong man.'

December 11, 1932-April 4, 2020

In his day, Frank Bray was one big, burly Irishman. "He was pretty 'swole,' as they say now," said his son, Jim. "When he was younger, he was a very strong man."Even in his later years, the former railway worker and hardware store manager cut a robust figure.

"He was one of these old-fashioned guys," Jim recalled. "He smelled of Old Spice. One of those typical, post-Korean War tough guys."

In February, Frank started showing signs of illness — fever, a dry cough, fatigue. In March, he tested positive for COVID-19. Jim's family shared Frank's home, and soon the entire household was sick — Jim; his wife, Jodi; and their two adult children.

Frank was hospitalized briefly, then Jim. While both were recovering at home in late March, Frank fell and injured himself.

"I was trying like hell to take care of Dad, but I was so weak," recalled Jim, who had lost 25 pounds during his illness. "I could barely carry a cup of coffee."

EMTs took Frank to the Northwestern Medical Center in St. Albans, where he suffered a stroke two days later. A few days after that, on April 4, Frank died without seeing his family again.

"The really hard part of it ... was that I couldn't be there when he passed away," his son said. Because of the coronavirus, the hospital did not allow visitors — and Jim himself was still in quarantine at home.

Frank was born on December 11, 1932, to Shirley and Madeline Bray. (And, yes, they were big supporters of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who was elected president a month before Frank was born.) Both parents lived and worked at Highgate Manor, where Frank was born. He would spend his entire life within spitting distance of the inn that, legend has it, was once a stop on the Underground Railroad.

"He didn't move very far beyond his doorstep, I'll tell you that," Jim said.

Not that he didn't try.

As the Korean War raged in the early 1950s, Frank tried to enlist, several times, with every branch of the armed forces. A head injury from his youth meant he was listed as 4F, medically unable to join.

"He tried like hell to serve," Jim said, explaining that Frank wanted so desperately to enlist that he tried to hoodwink several doctors, but none would sign off.

"So he just stayed home and worked hard," said Jim.

Fresh out of high school, Frank put his strength to good use moving freight for Central Vermont Railroad in St. Albans. Later, he took a job at Aubuchon Hardware in Swanton. He was soon sent to manage the Aubuchon store in Rouses Point, N.Y., and, thanks to a knack for solving problems, he eventually became the guy the company dispatched to help open new franchise locations.

"He was a big-time tinkerer," explained Jim, who tinkered himself for 20 years building sets and props for major movie studios. "You should see his shop in the basement. We've got tools to fix tools."

Frank met Marilyn Guay in the 1950s. She was a chef who trained in Boston under James Beard and was working at a local resort where Frank liked to go dancing.

"He saw her, and that was it," Jim said, describing his mother at the time as "a young Sigourney Weaver."

One night, Frank, who had taken dancing lessons in Montréal, asked Marilyn to dance and "swept her off her feet," Jim said. They were soon married and had Jim, their only child, not long after. They enjoyed a long and happy life together until Marilyn died in 2006.

Frank built the house in Highgate Falls where Jim grew up and now lives with his own family.

"There's little bits of his handiwork all around the house," Jim said. "His hand is everywhere in this house, so in that sense he's still with us."

Jim described his father as "very old-fashioned, patriotic" and a man who took great pride in his work and his family.

"He was very proud to have done what he could: to build a home, have a wife and a kid, and just build a life," Jim said.

— Dan Bolles

Helen Theresa Withers, 'She had a big, big, big heart.'

March 19, 1942-March 24, 2020

Helen Withers grew up poor in a small house across from Burlington International Airport, one of six siblings. When she had her own kids, according to son Eric Turnbaugh, she did everything she could to provide them with more than she had."She came from nothing and built her way up," Eric said. "She definitely had an appreciation for what a dollar was."

Following the dissolution of her first marriage, Helen raised three kids — Eric, Shawn Turnbaugh and the late Heidi Ziemba — by herself. She worked as a secretary at Burlington's Integrated Arts Academy, then called the H.O. Wheeler School, and attended Trinity College at night. In the weeks before Christmas, according to Eric, she would take a part-time job at Service Merchandise to pay for presents.

"She had a full plate at the time," recalled her longtime friend Ernestine Pratt, who worked with her at H.O. Wheeler. "I don't know how she did it."

Helen graduated from Trinity in 1981 and took a job at IBM, where she learned computer programing. A few years later, she met another IBMer, Garland Withers, in a square-dancing group, according to Pratt, who was also a member of the Green Mountain Steppers. Helen and Garland married in 1990 — and took part in square-dancing competitions throughout the Eastern Seaboard.

Helen's granddaughter, Krystal Turnbaugh, moved in with them when she was 7 years old. "She raised me," Krystal said. "I never missed out, even though I didn't have my own parents around. I didn't miss out on anything."

According to Krystal, Helen loved gardening, animals and basketball great Larry Bird, a poster of whom hung in her office at IBM. She could never have just one cat or dog at a time, because she feared the animal would be lonely. When she and Garland moved from Burlington to Jericho, she cultivated an enormous garden.

"She would plant tomatoes to the point where she would have so many that she would have to give them away," Eric said. "She wouldn't waste a thing."

According to Pratt, "She had a big, big, big heart — and she was always willing to give and to trust."

Not long after Garland died in August 2018, Helen began to develop aphasia and dementia. She eventually landed at Burlington Health & Rehab.

In early March, Krystal visited her there and took her out shopping. "It was great," Krystal said. "She was just herself again." They went to T.J.Maxx, where Krystal bought her grandmother a blanket with dogs on it and a stuffed dog and cat.

A week later, Helen was diagnosed with COVID-19. On March 24, a nurse urged Krystal to visit her grandmother. But by the time she made it to Burlington Health & Rehab and suited up in protective gear, Helen had died. She was 78 years old. When Krystal entered her grandmother's room, she saw Helen holding the stuffed animals.

"I was a couple minutes too late," she said.

— Paul Heintz

Thomas Lee Christian: 'He just knew everybody.'

April 25, 1938-April 10, 2020

Thomas Christian and Cynthia Severy started dating shortly before they graduated from Brandon High School in 1956, but they didn't tie the knot for another three years. "I told him I wouldn't get married 'til I was 21," Cynthia recalled. "I wasn't going to have my parents sign my marriage certificate!""If I had told him 31, he woulda probably still waited," she said with a chuckle. "I didn't know until afterwards how much of a crush he had on me."

The couple spent the next 60 years together, living in Thomas' hometown of Orwell and raising four children: Julie, Michael, Brian and Todd. They would eventually have three grandchildren and two great-grandchildren. "If he lasted 'til June, it would've been 61," Cynthia said of her husband.

He did not. After contracting the coronavirus from a family member, 81-year-old Thomas died from complications of COVID-19 at the University of Vermont Medical Center on April 10. Only a family friend who worked at the hospital was with him.

"I think the hardest part was that we couldn't be with him to say goodbye," his daughter Julie said.

Born in Rutland in 1938, Thomas spent most of his career driving trucks. He got his start on a local dairy route and eventually worked for Cumberland Farms, hauling milk from Addison and Rutland counties to Boston.

Gary Arnold of West Haven worked with Thomas at Cumberland Farms and later joined him at Carris Reels in Rutland. "We had a lot of miles together, a lot of conversations," Arnold said.

The men typically delivered the company's wooden reels to factories east of the Mississippi, but they once drove together to California — the first time either had made it to the West Coast. "Probably every place we stopped, he'd have the waitresses laughing before we left," Arnold said. "He just loved people."

Seemingly everywhere Thomas went, according to Cynthia, he would run into somebody he knew. "I wouldn't know them, but he would. He'd worked so many places and been in and out of the farmers' yards," she said. "He just knew everybody, and he was one that made friends very easily."

According to Arnold, Thomas was also quick to lend a hand. "You could be on one side of the interstate and, if you broke down, he'd turn around and help you out," Arnold said.

Thomas' work often kept him on the road all week, Cynthia said, and sometimes he struggled to adjust to the family's routine when he came home. But according to Julie, he tried to make it to his kids' sporting events — sometimes showing up in an 18-wheeler. In the summer, he would take them camping or to the Addison County Fair & Field Days, where every year he would help family friends show their cattle.

"He pretty much did what he could for us kids growing up," Julie said.

Later in life, Thomas became a Freemason and a Shriner. A veteran of the Vermont National Guard, he also joined the American Legion. According to Arnold, a fellow Shriner, Thomas particularly enjoyed driving the organization's mini cars in local parades. "He loved the kids and was always messing with them during the parade," Arnold said. "If he'd see somebody he knew, which was a lot of people, he'd just set and visit with them for a while."

In his final days, according to Julie, her father downplayed the severity of his condition. "He didn't want to let us in on how scared he was," she said. "I think he had a good life. He made the most of it."

— Paul Heintz

The original print version of this article was headlined "At a Loss | Coping with death in the age of a pandemic"

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

Tags: Coronavirus

About The Author

Chelsea Edgar

Bio:

Chelsea Edgar is a staff writer for Seven Days, and has written for BuzzFeed and Philadelphia magazine.

Chelsea Edgar is a staff writer for Seven Days, and has written for BuzzFeed and Philadelphia magazine.

find, follow, fan us: