Published May 1, 2013 at 11:48 a.m. | Updated October 19, 2020 at 5:09 p.m.

Not long ago, Seth Jarvis taught a playwriting workshop at a local high school. Introducing the Burlington actor and dramatist, a teacher mentioned that he also happened to work at Waterfront Video, which sparked a telling discussion.

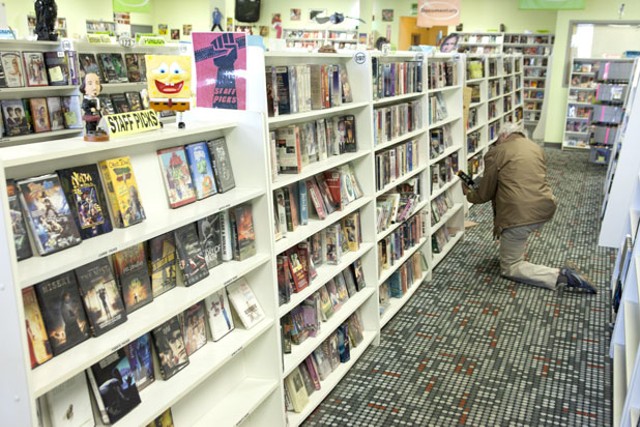

“During the break,” Jarvis recalls, “the kids talked about video stores — this historical relic.” He paraphrases in a breathy, excited voice: “‘Video stores used to be, like, a family could go in there on a Friday, and everybody could pick different movies! It was like they were going to the movies together!’ ‘Oh, yeah, I saw an episode of “Seinfeld” [about that]. They had staff picks, and it looked really cool!’”

At this point, older folks may be hearing a record scratch. Wait, what? When did video stores join the ranks of Eisenhower-era soda fountains, movie theaters with ushers and other things that only exist in myth, memory and TV reruns?

The teens’ waxing nostalgic about ye olde tyme video rental might have come as a shock to the customers who trickled into Waterfront Video last Saturday. Many were already jarred by a parallel sign of the times: a placard announcing the store’s imminent closing on April 30.

“Noooo!” one woman moaned theatrically.

Others told a reporter they didn’t know where they’d go now for movies. Browsing an online catalog wasn’t the same.

These customers knew about Netflix. They knew all the local Blockbusters had closed. But in their minds, Waterfront was special — a store with a catalog of 30,000 movies on DVD and VHS. A store where you could browse sections with names such as Made in Vermont and High Times. A store where you could count on finding the new François Ozon drama, an assortment of Troma films or the Brazilian street-kid film Pixote (out of print on DVD) alongside recent hits such as The Avengers. How could a store like that close?

Waterfront outlasted Blockbuster to become Burlington’s last video store. (Smaller rental outlets remain in South Burlington and Williston.) But in the end, changing trends — as signaled by those bemused teens — couldn’t be ignored.

When Seven Days broke the closure news on April 22, messages from longtime customers flooded Waterfront’s Facebook page. At the store on Saturday, renters sounded a similar refrain.

“I don’t like Netflix. I’m very disappointed,” said Donna Leban. “This is a great collection.”

At the counter, Gary Steller jokingly threatened the staff that he’d “throw a tantrum.”

Stan Bradeen of South Burlington said there was “no alternative” to Waterfront, “even online. All the rest of the places are just commercial,” he said. “This place was commercial and personal.”

Despite all this fervent support, the real question about Waterfront Video isn’t Why close it? but Why only now?

Staffers give primary credit for the store’s endurance to its cofounder and owner, Murray Self of Jericho, who passed away last September. A kitsch lover with a well-known fondness for purple and Hawaiian shirts, Self kept the store open through good times and bad.

“He was very much about keeping the store running as a community resource,” Jarvis says. “Even though it may have been smarter from a purely business perspective to say, ‘Get rid of the VHS,’ or to shrink the operations to a great degree, he felt it should exist at the same level for as long as we could keep going.”

Self’s generosity helped Waterfront weather “upheavals,” including a physical one: In 2005, the store had to vacate its original Battery Street location. It ended up way off the waterfront, in a strip mall on Shelburne Road next to a Burlington post-office outlet, and rebuilt its customer base without the foot traffic from downtown colleges and bars.

But to focus on such setbacks is to ignore the forest for the trees. In 2011, research firm IBISWorld declared video rentals one of the top 10 “dying industries.” If video killed the radio star, Netflix, Redbox and broadband internet access killed the video store. Many of the people Seven Days spoke with for this story — movie addicts with fond memories of renting from Waterfront — admitted they now order online, DVR, stream or illegally obtain most of their entertainment.

Brooke Dooley of Burlington, a former Waterfront employee, sums it up: “Instant gratification is something we’ve become accustomed to in the past 10 years.”

Though we may be addicted to right now, we can still take time to remember a business that inspired its customers to linger. Soon we may need to tell our stories about video stores to kids who ask, “What’s a DVD?”

A “new contender”

Here’s a reminder of how much has changed since Waterfront Video opened in December 1996: Back then, customers with tough movie questions could consult staff members, guide books or … CD-ROMs.

This high-tech feature was mentioned in a November ’96 article in the now-defunct arts weekly Vox. Writer Susan Green hailed Waterfront as the “new contender among local video stores” and went on to describe its striking décor, including a velvet Elvis painting, green Naugahyde chairs and Formica counters with a boomerang motif.

That retro design was the brainchild of original co-owner William Folmar, whose friend Judy Hill created the store’s logo.

Folmar, who still lives in Burlington, recalls in a phone interview that he had considered opening a video store for years, “one with a little bit of everything, that especially focused on foreign and independent film.” For a while, South Burlington’s Empire Video seemed to be filling that niche. Then Empire sold out to Blockbuster, which quickly evolved into the McDonald’s of video-rental outlets. “I started thinking, Maybe we could still do this,” Folmar says.

He’d been “planning on a small store.” But one day his friend Murray Self, in his car waiting for a green light at College and Battery, noticed that half of the S.A.S. Auto Parts building, with its lake-facing windows, was vacant. The 4400-square-foot space was more than ample.

“Murray wasn’t going to participate originally,” Folmar recalls, “but when we decided on the larger footprint, he said, ‘I’ll go in on this with you.’”

Originally, Folmar says, they considered kitschy names like “Videorama” for the store. They settled on the descriptive “Waterfront” “because people from Montpelier can come find it.”

Folmar and Self spent $180,000 to remodel the space and open the store with 4000 titles. In those pre-DVD days, distributors sold VHS tapes to stores at inflated “rental prices,” which made nonreturns and delinquent customers a serious problem. Still, the catalog grew.

So did the staff. One of the first to come on was Peter Pritchard, an amateur filmmaker who’d just graduated from high school. Pritchard, who now lives in Boston, recalls a friend of his mom’s telling him, “There’s this really cool independent video store opening up. I bet they would hire you.”

Soon Pritchard was cataloging tapes in Folmar’s living room and building shelves to display them. He stayed nine years.

Jarvis found his way to Waterfront in its first year. When the store opened, he recalls, “We were all excited, all the movie buffs in town. We went down and got all geeky.” He ended up watching Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin on the store monitor, listening to two staffers debate the merits of different musical scores for the silent classic. “I was like, This is where I’m gonna be!”

Soon Jarvis’ cinephilia propelled him into the role of buyer, building and curating the store’s catalog from the fatter into the leaner years. Folmar says now, “His contribution to how well the store works cannot be overstated.”

A hit

One of Waterfront’s all-time biggest rental weekends was during the ice storm of January 1998. “We were slammed from opening to closing every night,” Jarvis recalls. People rented stacks of movies, Folmar remembers, only to call and say they’d lost power and couldn’t retrieve them from the VCR.

While that weekend was extraordinary, Waterfront “was a booming business” in the late 1990s and early aughts, Jarvis says. “Your home-viewing options were limited, so people used us a lot.” The store stayed open until midnight, catering to the student crowd, and Pritchard recalls, “Fridays and Saturdays were just, like, crazy in there.”

“It was amazing how quickly it took off,” Folmar says. He credits some of the store’s early popularity to local college profs who referred students to Waterfront. In 1998, the store opened a satellite in another college town — Middlebury.

Around 1999, DVD players began cropping up in households. With the new format still pricey, Waterfront had an “in-house debate about whether to jump into it or not,” Folmar recalls. “Thank God, we did.”

Knowing how quickly Blockbuster could build a DVD catalog, Jarvis says, he was convinced Waterfront had to beat it to the punch. “We started early on, and we didn’t have to scramble when the switch became clear.”

Soon the store’s Naugahyde “living room” was full of squeaky DVD carousels, which would continue to share space with VHS shelves to the end.

Location trouble

In 2000, the Burlington Community Development Corporation — an arm of Mayor Peter Clavelle’s administration — purchased the complex at College and Battery with the aim of transforming it into the city’s transportation hub. The plan fell through, but the writing was on the wall for Waterfront. “We knew for a good two and half or three years we had to be looking [for a new space],” Folmar says.

That didn’t make finding one any easier. In 2004, April Cornell made a purchase offer on the building, and Waterfront received a notice to vacate. At the time, Folmar told Seven Days he worried he might be “spending the next 10 years on eBay trying to sell my inventory.”

With financial support from the city, Waterfront left the waterfront in April 2005 and moved into the former Alpha Graphics space at 370 Shelburne Road. The 16 employees scrambled to fit their catalog into 3800 square feet.

“It took us a long while to rebuild the customer base,” Jarvis says. On the edge of suburbia, the store developed a clientele that was “older, more family oriented.” The hours became earlier, the staff smaller, the nighttime renters “more sober,” Jarvis says. “Nobody came in and insisted on us serving them fried chicken or anything.”

Did the move spell the beginning of the end for Waterfront? “Things never got back to the level we were at,” Jarvis admits. But he points out that the move “happened to coincide with the rise of Netflix and other alternative sources. It’s impossible to say where things would have been if we kept the Battery Street location.”

Folmar, who sold his share of the business to Self in 2005, says, “I do think [the store] would have been doing better had it been able to stay at the waterfront.” Yet, he points out, a stable location didn’t save the Middlebury store, which closed in 2011. “The whole industry has just been sinking,” he says.

Not your average retail job

Waterfront eventually shrank from 16 employees in 2005 to six when it closed its doors. Some of Burlington’s young professionals will surely retain vivid memories of days and nights spent behind the counter.

Alex Martin of Winooski, who worked at Waterfront from 1999 to 2001, calls it “the best job I ever had, easily. Mostly because I worked with so many great people.”

“Some of the best friendships that I’ve had came out of that store,” Pritchard says. “It was a fun, cool place to work.” He remembers vehement arguments with other staffers “about why a film was good or why it was horrible.”

“It was my Empire Records,” Dooley says, referring to the 1995 cult film about an indie music store. “It wasn’t a job, because we hung out together. We dated each other. Everybody had apartments together.”

Indeed, Waterfront has spawned at least two marriages, staffers say. Jarvis met his now-fiancée when they both worked there.

Dooley, an employee from 2000 to 2003, remembers feeling like there was a “Waterfront cachet — probably just a cachet that we created in our own minds.”

Staffers got recognized around town. Martin was known for the seal of approval on his staff picks: “Alex says, ‘It’s money, baby.’” (Swingers lingo was still fresh in the public imagination.) Sometimes, he says, customers would stop him downtown to enthuse, “You were so right, that [movie] really was money!”

Were employees as friendly to customers as they were to one another? Jarvis acknowledges that, when the store was on the downtown “hipster circuit,” some employees could be a tad condescending to renters with lowbrow tastes. The store became “friendlier” in the second half of its life, he says.

When customers specifically wanted to discuss highbrow films — especially French ones — they often sought out George Holoch, who passed away last month. Older than most of the other employees by a generation or two, Holoch came to Waterfront in 1997. When he wasn’t at the store, he was busy being the award-winning translator of French works such as Michel Pastoureau’s The Bear: History of a Fallen King.

When it came to movies, Holoch had strong opinions. Folmar calls him “sort of like the pit bull of the store, and I mean that in a good way.”

“He had people who would rather wait in line for him than let an available clerk check them out, just because they wanted to chat with him,” Jarvis says. “Anyone who could speak French did speak French to him.”

The final chapter

When Netflix started to catch on around 2005, Jarvis says, “It was like, Video stores are done. And then things would change within the industry, and it was like, Maybe not, maybe we’ve got some more time.”

Movie studios helped out video stores by introducing release “windows” that gave them earlier access to hot titles. And Folmar notes that the advent of TV boxed sets “saved our bacon, for a while at least.” Customers addicted to a series didn’t want to wait for discs to arrive in the mail.

Manager Chris LaPointe came to Waterfront while studying at Burlington College and has worked there for six years. He says he saw the store as operating “in conjunction” with services like Netflix. Still, he adds, “You’re gonna get the customers who are like, ‘I’m not gonna pay my late fee; I’m gonna go to Redbox!’ And you’re like, ‘Well, OK, I’m sorry you feel that way, but this is how we have to run.’”

Then came online-streaming services, which offered instant gratification with no late fees. And video stores around the country kept shuttering.

“It was because Murray was about covering us through those really tough patches that we were then able to turn around,” Jarvis says of the industry’s setbacks.

After Self’s death at 56 left the store without its “patron saint,” Jarvis and others looked into ways to make Waterfront profitable. They considered moving to a still smaller location, or adding a retail arm and a café. But none of those options was viable without “large investments of capital,” Jarvis says. “We just weren’t able to find a person or persons who could do that in the time it needed to happen.”

What did materialize was a buyer for the store’s extensive inventory: Randy Senior of Selection Video, a South Burlington-based business that supplies small home-video outlets, such as convenience stores on Grand Isle. Senior hasn’t announced any plans for the collection.

Saying good-bye

“Are you going to sell off the movies? Can I buy some?” was perhaps the No. 1 question heard at Waterfront Video on Saturday evening. LaPointe and other employees patiently explained to one customer after another that the stock was spoken for.

Renters also bemoaned the loss of a browsing spot and a community. Some said they’d miss the employees as much as the movies. Bradeen, who said he’d been renting from Waterfront since it opened, called them “intelligent, personable and fun.”

“We have a number of customers who just want to come in and talk,” LaPointe said. “I think I will miss that the most, the conversations that I got to have here.”

Since news of the closing broke, “People have been extremely kind,” Jarvis added. “They’ve brought in cupcakes and sweets, offered career counseling and such.”

“It kind of vindicates, in a way, that we’re seen not just as a store but as a place to have a conversation, a place to connect with people,” LaPointe went on. “It’s been great to see that over the last couple days.”

With the last movie due dates approaching, choosing between a French art flick and a VHS-only rarity was suddenly harder than ever. True, some customers were mainly there to grab Django Unchained (all the copies were out). Others browsed and talked. Movie clerk Sarah Daley jotted down a list of titles in the wildly eclectic Off Beat section — material, perhaps, for a future Netflix queue.

The atmosphere was low-key, but every now and then there was a surge of emotion. “Bye, everybody, feel good,” a woman called on her way out. “Thank you for bringing art to the world!”

Video stores may be among those businesses that are more widely mourned at their demise than patronized in their decline. Former employee Martin suggests that Waterfont is “one of those things people are going to miss more when it’s gone.”

On Saturday, there was no denying that online commerce had won one more battle. Yet responses to the closing were still full of local pride. With help from Self’s generosity, Burlington had sustained an indie video store longer than a Blockbuster.

“They wouldn’t be here if it weren’t for the community,” Bradeen said of Waterfront, “and the community wouldn’t be the same without them.”

VIDEO: The Last Days of Waterfront Video on "Stuck in Vermont"

Tales From the Porn-Rental Trenches

Carrying art films wasn’t the only thing that set Waterfront apart from vanilla Blockbuster. There was also the porn.

Many of Brooke Dooley’s most vivid memories of working at Waterfront involve the adult films. “There was one other woman on staff. And a whole bunch of serious dudes,” she recalls. “Dude dudes. It was interesting to watch how people renting porn would react to the male staff and then to us.” Most of the renters were men who made a beeline for male staff members, she says, though “sometimes there would be the shy and awkward couple getting porn together.”

On one occasion, a couple inadvertently contributed to the collection. Dooley recalls a fellow staffer calling her “screaming” after he discovered an amateur porn tape in the return box. “I put it on the monitor in the back office,” she says. The clerks identified the renter “from her homemade porn, which her boyfriend inadvertently dropped off. The guy came back; he was like, ‘Um, I think I dropped something.’”

Then there was the renter new to Burlington who arrived on a bicycle, loaded it up with adult tapes and a rented VCR, pedaled off, and returned everything two hours later. “I wouldn’t touch any of it,” Dooley says.

When she recognized people around town, she found herself wondering, “I don’t know if I know you from stuff, or if you just rent a shit-ton of porn.”

Awkward moments aside, Dooley says doling out the adult films “made me more liberal as far as [thinking] it’s not a big deal. It changed my opinion on dudes and why dudes spin porn. And women, too.”

A Selection of Recent Staff Picks (and Their Box Stickers)

George Holoch: “George Recommends”: 35 Shots of Rum, Day of Wrath, César and Rosalie

Chris LaPointe: Chris says “Two Thumbs Up!”: “Archer,” Fire and Ice, Ninja Scroll

Todd Scott: Is this any good? I like to think so: Misery, Carrie, The Mist

Nate Foltz: Nate says “Nearly Perfect”: Space Jam, The Fly, Videodrome

Seth Jarvis: Seth Dares You: The Point, Rango, Mary and Max

April Edwards: The April Abides: Steel Magnolias, Norma Rae, Forrest Gump

Sarah Daley: There’s just something about this movie: The Illusionist, Waltz With Bashir, The Dangerous Lives of Altar Boys

More By This Author

About the Artist

Matthew Thorsen

Bio:

Matthew Thorsen was a photographer for Seven Days 1995-2018. Read all about his life and work here.

Matthew Thorsen was a photographer for Seven Days 1995-2018. Read all about his life and work here.

Speaking of Movies

-

Next Month Brings the Final Curtain for Palace 9 Cinemas

Oct 27, 2023 -

Book Review: 'Save Me a Seat! A Life With Movies,' Rick Winston

Aug 30, 2023 -

Steve MacQueen Named Executive Director of Vermont International Film Festival

May 22, 2023 -

Vermonters Are Going Back to the Movies — Under the Stars

Aug 26, 2020 -

Where to Catch a Movie Near Burlington

Sep 11, 2018 - More »

Comments

Showing 1-1 of 1

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.