April 29, 2020 PAID POST » Business

Published April 29, 2020 at 10:00 a.m.

February 4, 2020, will go down in Vermont history as the day Commissioner of Health Dr. Mark Levine first briefed the governor's cabinet about the threat posed by COVID-19. But it marked another sad milestone: Robert "Bobby" Miller died of a heart attack at age 84.

Miller was a real estate developer. He was also one of the state's "most generous — and most colorful — philanthropists," wrote Paula Routly in a story published the following day on the Seven Days website. "A self-made man who grew up dirt poor in Rutland, Miller gave away millions to Vermont nonprofits in cash donations and in-kind work through his company, REM Development."

Related Developer and Philanthropist Robert 'Bobby' Miller Dies at 84

Developer and Philanthropist Robert 'Bobby' Miller Dies at 84

Off Message

In a recent interview, his daughter, Stephanie Miller Taylor, speculated that her father "probably gave more of his time than his money." Indeed, the program for his memorial service included a saying of his: "To truly live life to the fullest, you must share the three Ts — Time, Talent and Treasure." Bobby Miller shared them all, and he helped shape his home state — its leaders, institutions, built environment and people.

As Vermonters face unprecedented economic hardships resulting from the novel coronavirus pandemic, Miller's philosophy of giving back to the community has become especially relevant. Said Stephanie: "I think that's what we're going to need going forward as a society."

Overcoming Obstacles

Bobby Miller didn't have an easy childhood. His left arm was amputated at the elbow at birth, which set him apart as a kid but didn't slow him down. Growing up with one arm meant that overcoming obstacles was "baked into his DNA," said Lake Champlain Regional Chamber of Commerce president and CEO Tom Torti.

And there were many obstacles. In a 2000 profile in Seven Days, Miller described his family as "very dysfunctional." His obituary noted that his mother held three jobs and his father struggled to find work. In high school, Miller moved in with his grandparents.

Related Obituary: Robert E. “Bobby” Miller, 1935-2020: Community philanthropist and family man believed in giving back

Obituary: Robert E. “Bobby” Miller, 1935-2020

Community philanthropist and family man believed in giving back

Obituaries

The third of six siblings, Miller was hardworking and resourceful. As a teenager, he made money by renting a garage, working on cars at night and returning them to their owners in the morning on his way to school.

Miller never went to college. He worked for an engineering firm in Connecticut before moving back to Vermont in 1959 and getting a job with a firm in Burlington. He started New England Air Systems in 1972. Twelve years later, he sold the company to his employees and founded REM.

More Than Just Money

As a commercial real estate developer, Miller worked on projects in Rutland, Newport and Burlington. He found creative ways to spur economic development. "Nobody could put together a deal like him," remembered Stephanie, who is the vice president and marketing director at REM.

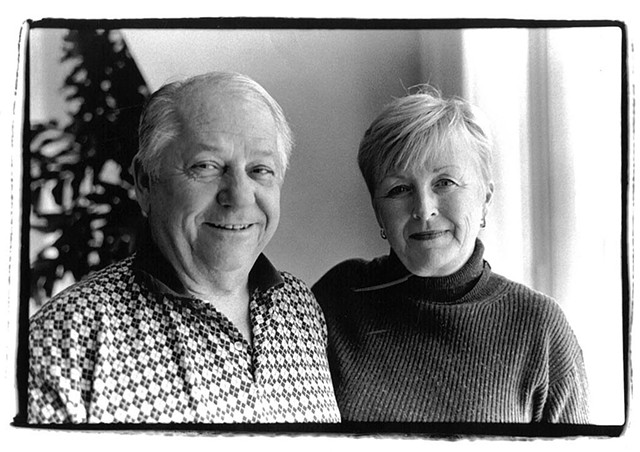

In January of 1986, Miller married his second wife, Holly. Like him, she had grown up in Rutland and hadn't attended college. The couple became committed philanthropists focused on helping women and children, promoting education, and supporting end-of-life care. They made generous donations to many causes and entities — including the King Street Center, the Boys & Girls Club, Champlain College, the Visiting Nurse Association, the Flynn Center for the Performing Arts and the VNA Respite House. Their 2013 gift to the University of Vermont Medical Center was valued at $13 million.

In addition to money, Miller donated in-kind support. He would help structure a real estate deal, then make it happen as cheaply as possible, paying contractors for their work but not taking a cut for himself. "He was going to buy all the materials, and they would be at cost," said Torti. "That was Bobby Miller."

For example, he built the Miller Center at Champlain College's Lakeside Campus for roughly $150 a square foot, according to David Provost, who was at the time the college's senior vice president of finance and administration. The building, which houses Champlain's Emergent Media Center and the Senator Patrick Leahy Center for Digital Forensics & Cybersecurity, could easily have cost three times as much, Provost said.

Miller didn't do the project just to help Champlain; the building jump-started development along that part of the Pine Street corridor in the South End. Shortly after it opened, Feldman's Bagels launched nearby. The Cumberland Farms gas station got a makeover. The Great Northern restaurant arrived, as did Generator maker space and City Market, Onion River Co-op's South End store. Hula, a new tech campus on the site of the former Blodgett Oven factory, is under construction.

Miller anticipated that helping Champlain would help Burlington, Provost said. "That was the spirit of how he saw things."

Investing in People

Miller also leveraged relationships to help others whenever he could. When Champlain was building a residential hall in 2006, Miller asked Provost whether the school would consider hiring a woodworking shop he knew of in the Northeast Kingdom, to keep them employed. The school ended up contracting with that company to make more than 100 beds and dressers.

Provost noted that Bobby "treated everyone the same." He and Holly would sometimes eat in the dining hall. "All the employees in that dining hall knew the Millers," he said, "and he knew them."

Executive chef Sandi Earle befriended Miller while catering trustee dinners at the President's House. She recalls that he would tell her, "Sandi, one day you're going to want to do something and need a little help with it. When you do, please come see me." In 2017, Earle went to him with a request to fund a cookbook she'd been working on, as well as a book release party that would benefit the Vermont Family Network.

She had intended to ask Miller for a $10,000 loan, but before she could ask, he offered that amount as a contribution. It helped Earle produce My 30-Year Love Affair With Food in Vermont. "He never expected anything in return except a copy of the cookbook once it was published," she said. "I will forever be grateful for his generosity."

Miller also helped Provost, becoming a mentor to him, teaching him about construction and navigating governmental systems. Like Miller, Provost grew up in a working-class family and had five siblings. "He really helped guide me on a daily basis," said Provost, who now serves as the executive vice president for finance and administration at Middlebury College. "He helped shape me into the leader that I am."

Giving Back Feels Good

Bobby and Holly Miller were public about their philanthropy, mainly to encourage others with the means to give.

As a result, many Vermont buildings bear the Millers' names: In addition to the Miller buildings at Champlain College, there's also Robert Miller Community and Recreation Center in Burlington's New North End and the McClure Miller VNA Respite House in Colchester. Bobby died in the Robert E. and Holly D. Miller Building at the UVM Medical Center; his memorial service took place in the Robert E. Miller Center at the Champlain Valley Exposition.

But Bobby Miller didn't give just to see his name on buildings, said daughter Stephanie. "It made him feel good to give back," she said.

Torti has more than one story of Miller whipping out a checkbook or a wallet full of cash to give a contribution on the spot. He and Miller were having breakfast at a diner in 2019 when a crowd of Vermont Air National Guard members arrived. Before leaving, Miller beckoned the diner's owner over and gave him a few hundred dollars in cash to pay the Guard members' bill.

The owner said it was too much; Miller told him to give whatever was left to the waitstaff.

Torti asked him why he paid the bill. "He said, 'They're taking a lot of grief in the press, and nobody does anything nice for 'em,'" Torti explained, adding, "They didn't know he was Bobby Miller."

After witnessing one of these random acts of generosity, Torti said, "You know, Miller, I wish I could do that.'" He said Miller told him to forget the dollar amount. The important thing is to give a little bit more than is comfortable. He said when he and Holly would sit down to go over their contributions, "'We know we've given enough when we feel the pain a little bit.'"

It's a good lesson to reflect on during this crisis, when tens of thousands of Vermonters are out of work and going hungry, when businesses, nonprofits and the state government are struggling.

To get through this, Torti said, "everybody who can should try to stretch and feel a little bit of pain. That's what Bobby would have done."

This article was commissioned and paid for by Pomerleau Real Estate.

More By This Author

Speaking of...

-

Field Guide: Steve Hadeka

Sep 11, 2019 -

Gather Round: A Guide to Community Centers in Burlington

Sep 11, 2019 - More »

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.