Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

-

Education

Scott Official Pushes Back on Former State…

-

News

Burlington Budget Deficit Balloons to $13.1 Million

-

Education

Senate Committee Votes 3-2 to Recommend Saunders…

- Court Rejects Roxbury's Request to Block School Budget Vote Education 0

- Norwich University Names New President Education 0

- Media Note: Mitch Wertlieb Named Host of 'Vermont This Week' Health Care 0

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

Hooked: How So Many Vermonters Got Addicted to Opioids

Published February 20, 2019 at 6:00 p.m. | Updated May 3, 2022 at 6:02 p.m.

"Why are so many people addicted to heroin in Vermont?"

The man who asked me this question was middle-aged, with a shaved head and eyes whose earnestness matched his query. We were in the produce department of a grocery store, each with a mostly empty basket slung over an arm. He'd seen my photo when Seven Days announced that I'd be writing about the opioid epidemic in Vermont and stopped me as I shopped for broccoli. "How did this happen?" he wanted to know.

His questions are among the many I've been asking since my sister died last fall, since she became addicted to heroin more than a decade ago. They're part of the reason I took a job writing about the opioid epidemic when my only credentials are loving someone who struggled with a disease that destroyed her life and writing an obituary about her that went viral.

What just happened? I asked myself as my mom and I left the hospital room where we'd spent the previous three days and nights at my sister's side. This isn't happening, I thought as we stepped into the elevator and were transported farther and farther away from her body. For the 12 years she'd been addicted, we had never given up, never let go, never stopped believing, and now we were leaving her behind. How did this happen? I've asked myself every day since.

I may spend the rest of my life trying to answer that question, but why so many people are addicted to heroin can be explained over a pile of broccoli in the supermarket. The explanation is not unique to Vermont and has been addressed in books like Beth Macy's Dopesick, which traces the development of the opioid epidemic in Virginia, and Barry Meier's excellent reporting in Pain Killer and the New York Times. It can be distilled into something so simple you can hold it in the palm of your hand, so small you can put it in your mouth and swallow it. The shortest answer to that question is a pill.

click to enlarge

- Courtesy Of Kate O'neill

- From left: Maura O'Neill, Kate O'Neill, Madelyn Linsenmeir and Maureen Linsenmeir in 2016

My sister, Madelyn Linsenmeir, was 16 the first time she fell in love — not with a boy from school or a girl she met at summer camp, but with a pill she took at a party. Or more accurately, she fell in love with the way that pill made her feel.

A friend whose father died because of his addiction said her dad described trying heroin for the first time as "feeling the jigsaw piece that had been missing inside him his entire life click into place." I wonder if that's what it felt like for my sister. If something was missing, and when she took that first pill, she felt whole. Or maybe it just made her feel good, the way a beer or a joint can make a teenager trying them for the first time feel good, and she didn't understand that the pill she took was different from a beer or a joint. That it was a highly addictive, opioid-based prescription painkiller called OxyContin.

Whatever the case, she continued to take oxys, as they're called, and soon had developed a dependency on opioids that she could no longer afford to sate through expensive black-market pills, and she began shooting heroin. Later she would fall in love with needles, injecting water when she was sober because she missed the feeling of the needle slipping beneath her skin. Then she fell for a man who was also addicted to opioids and with whom she would spend years spiraling in and out of sobriety, in and out of rehab, in and out of jail.

Eventually she fell in love with a baby. Everything was different after she had her son, and we were sure that this time she would stay sober. But her love for her son was no match for the call of that drug; not even he was enough to save her.

My sister was not the only Vermonter who discovered OxyContin, which was developed by Purdue Pharma, a Connecticut pharmaceutical company. Released in 1995, it was a new formulation of the opioid-based painkiller oxycodone. Purdue claimed that OxyContin was less addictive than standard oxycodone because it was timed-release, meaning it is slowly absorbed into the bloodstream. Based on this claim, the company engaged in an aggressive campaign to market the medication to doctors.

At the same time, doctors were feeling pressure on another front. In 1996 the American Pain Society introduced the idea that pain should be considered a vital sign, just like pulse and respiration rates, blood pressure and temperature, and doctors were expected to measure and treat it accordingly.

Related Evolution of an Epidemic: A Timeline of the Vermont Opioid Crisis

Evolution of an Epidemic: A Timeline of the Vermont Opioid Crisis

Hundreds of Vermonters have died from opioid overdoses in the past quarter century. Eight thousand are currently in treatment for opioid-use disorder. Countless more live every day with the despair of this disease. How did we get here? No single event sparked Vermont’s current emergency, but its momentum was building for more than a decade before then-governor Peter Shumlin named it a “full-blown heroin crisis" in his State of the State address. From the invention of OxyContin to a single night last month when the University of Vermont Medical Center treated seven overdosing patients, our timeline tracks the epidemic in Vermont.

By Kate O'Neill

Opioid Crisis

Harry Chen, who was an emergency room physician in Rutland for two decades before serving as Vermont's commissioner of health from 2011 to 2017, told a story to illustrate what this meant: A patient would be sleeping soundly — "snoring," Chen said — "and the nurse would have to wake them up to ask them how bad their pain was." That practice contributed to an epidemic of overprescribing.

"Truth be told, I was participating in it, based on what I thought was best for my patients," Chen said. "Physicians were to some extent misled, and ... when the hospital administration says they don't want to hear complaints from patients about not having adequate pain medication, you start giving pain medications."

Chen was just one of many: "The current epidemic began and was fueled in part by the good intentions of the medical profession believing that addressing pain was a necessary component of the care of individuals," said Bob Bick, chief executive officer of the Howard Center, a Chittenden County-based social services agency.

The result was a 300 percent increase in the number of opioid prescriptions between 1991 and 2009, according to the Pharmaceutical Journal. The federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention notes that the total number of opioid prescriptions peaked at more than 255 million in 2012: That's 81.3 prescriptions per 100 people in the U.S.

In the Green Mountain State, the number of opioid prescriptions reached 538,403 in 2014, which amounts to a prescription for five out of six Vermonters.

In fact, OxyContin is not less addictive than oxycodone, and patients who took it as prescribed often found themselves physically dependent on the drug. "A kid has four wisdom teeth out, they get a bottle full of pills," said Chen. "The next thing you know, they're addicted."

And people quickly figured out how to hack the tablet's timed-release mechanism: By crushing the pills and then snorting or injecting the drug, they were able to get an intense high.

By 2000, sales of OxyContin had reached $1 billion; four years later, it was a leading drug of abuse in the United States. In 2007, Purdue Pharma and three of its top executives pleaded guilty to felony charges related to mis-marketing the drug as nonaddictive. But by then it was too late: More than a million Americans — including thousands of Vermonters — were hooked on opioids.

- James Buck

- Katie Counter

Picture a girl with light-blond hair. She's wearing purple overalls, standing in a field picking flowers. Katie Counter imagines that girl, her 4-year-old self, and asks herself, Would you treat that little girl the same way you treated yourself all of those years you were using?

Katie, now 35 and living in Burlington, was 15 when she took her first OxyContin. It was 1998; Purdue had released the drug three years earlier. She'd stolen the pill from her grandfather, whose doctor was notorious for overprescribing in her hometown of Brandon.

By the time she was 16, she was using heroin.

I met Katie for the first time after we appeared together last December on a Burlington Free Press panel about the opioid epidemic. She was captivating in her purple shirt and bow tie, her raw honesty moving the audience and other panelists to laugh and cry and then laugh again. When we were introduced, she told me she'd known my sister — they'd been in rehab and jail together on multiple occasions.

"I have a friend here," I could hear my sister's voice as she called from the Chittenden Regional Correctional Facility in South Burlington. But the woman standing in front of me was not the Katie I had pictured when Maddie told me someone was helping her navigate jail.

I'd imagined someone tough, and Katie is — she swears a lot, and her everyday uniform is baggy, low-slung pants, a sweatshirt and a baseball cap, an outfit that compels the security guards at Target to follow her through the store as she shops.

But the wide brim of her baseball hat is generally turned back, exposing beautiful gray-blue eyes that are expertly lined and shaded with silvery shadow, a face that moves quickly from scowl to smile. She is not a hugger, she told me the second time we met, at a downtown Burlington café. But when we got up to leave, I forgot and hugged her anyway, because she is tough but she is also huggable, and when I did, she hugged me back.

"She was too open when she first got to jail," Katie said about Maddie. "'You have to put on your jail mask,' I told her. 'You have to put on your jail mask, or they'll kill your heart.'"

As she told me stories about my sister, I wanted her to be sitting there with us. I wanted Maddie to tell me what happened, to fill in the missing parts, to explain what went wrong, how we failed her, what could have saved her.

But my sister is dead, so instead I asked Katie, who is miraculously, gloriously alive, to share her story with me, and she did.

If you look to Katie's childhood for clues that perhaps she would later abuse drugs, you can find them: Her mother abandoned her; she was sexually abused for years by an uncle; she was exposed to drug use at a young age; when she was 11, her father married a woman with four kids and Katie often felt excluded from the family.

But you could also find evidence that argues against addiction: She excelled at sports from the time she was in elementary school. Her father was a constant presence in her life, and Katie loved the 11 years when it was just the two of them, her dad coaching her softball team, the days he would bring her to the maintenance building at the Brandon Training School where he worked and give her a sugary cup of coffee to sip while he made shelves for her stuffed animals.

"I didn't realize what I was getting into," Katie said about the first time she used heroin. By then she was so addicted to pills that she would get sick if she didn't swallow or crush and snort them. Her boyfriend brought her to a place in Pittsford, "the Vermont version of a trap house," she told me. "You go in, you get stuck, you can't leave." The house was filthy, dirty dishes everywhere. "A cow wouldn't walk in there," she said, "and I don't like dirt. But your standards go from here," she held her hand high above her head, "to here," she lowered it below her waist.

The dirt didn't matter once she'd tried heroin for the first time. Nothing did: She was in love.

It has been almost five months since my sister died, but I still cry easily. I don't know if others would be brought to tears scrolling through Vermont headlines from 2000 and 2001: "Governor Calls for Crackdown on Heroin"; "Committee Recommends Methadone Treatment Program"; "Girl's Death Exposes Sex Trade: Vt. Teens' Heroin Use Tied to Bronx Case"; "Big-City Scourge Besets Rural State: Vermont Struggles with Influx of Heroin"; "Hospitals Wary of Setting Up Methadone Clinics."

This is not just the story of a pill.

Several years before Katie and my sister swallowed their first OxyContin, Vermont had an opioid problem. It was minor compared to what was to come, and it was heroin that people were worried about, not the prescription painkillers their friends and neighbors and family members were quietly becoming addicted to. But even then it was described as an "epidemic." From the governor to the guy reading the paper at the bus stop, Vermonters knew opioids were here.

At my computer 17 years later, I read a December 2002 opinion piece in the Burlington Free Press titled "Hearing the Alarm," which noted that "once Vermonters grasp the seriousness of a social problem they usually respond. That seems to be happening with heroin addiction, which has reached epidemic proportions in Vermont."

We knew.

Picture a 4-year-old girl with light-blond hair. She's wearing purple overalls, standing in a field picking flowers. Picture a 7-year-old boy with brown skin. He's zooming a toy dump truck back and forth across his bedroom rug. Imagine that child grows up to have a disease — maybe it's diabetes, maybe it's opioid-use disorder. Imagine it's your daughter. Imagine it's your dad. Imagine it's you.

We knew, and we didn't do enough to stop it. I laid my head on my desk and wept.

For years he had opposed the idea, advocating instead for increased law enforcement. He claimed methadone would be a "magnet of addicts" who would come to the state seeking treatment and then harm communities. He was, he said, just trying to protect Vermonters.

But the lead author of the committee's report, then-state senator James Leddy, believed that by not allowing methadone treatment, the state was in fact failing Vermonters: "We're doing very little for heroin addicts in this state," he told the Burlington Free Press. "The evidence is overwhelming that if we're going to provide treatment for heroin addiction and do not use methadone as part of the program, we're going to fail."

Dean, a physician, wasn't having it. He reiterated his past objections and pointed to University of Vermont studies on a medication called buprenorphine that was also proving to be an effective treatment for opioid addiction. Dean preferred it to methadone.

But buprenorphine had yet to be approved by the U.S. Food & Drug Administration, and the only people who could take it were participants in the studies, for which there was a waiting list. Additionally, buprenorphine was intended as an alternative to methadone, not a replacement for it.

In the spring of that year, when the state Senate passed a bill that would allow methadone clinics, Dean vowed to veto it and, in turn, received a scolding from the country's drug czar, Gen. Barry McCaffrey.

"Does this mean we're going to outlaw Prozac so that depressed, schizophrenic patients won't move to Vermont?" McCaffrey, then director of the Office of National Drug Control Policy, asked while speaking at a San Francisco conference on methadone. "Oh, by the way, governor, heroin abuse is in the state of Vermont."

Eventually Dean agreed to sign a bill that permitted methadone treatment, but not at clinics: The medication could only be dispensed by hospitals. A year after the bill passed, only one of the state's 16 hospitals had agreed to prescribe it for addiction.

When the Rutland Regional Medical Center proposed the idea in April 2001 to the physicians who worked there, 53 of them signed a petition against it. Chen suspects that he was one of them but said he can't "specifically recollect."

"We care for the patients in this community. We've cared for them for generations," a hospital radiologist told the Burlington Free Press at the time. "This is our community and we want to keep it pristine."

While Rutland may have been "pristine" in the eyes of that radiologist, just a few months before he made his remarks, the city's chief of police told the Associated Press that heroin use was "at epidemic proportions in Rutland" and responsible for a recent, large increase in crimes such as burglary and theft.

The same year the city's doctors said no to methadone, its citizens voted to pass a 1 percent rooms-and-meals tax to pay for two cops who would be dedicated to investigating drug crimes. This kind of approach is what many of the people I interviewed described as trying to "arrest our way out of the problem." They also characterized it as a failure.

In 2002, Vermont finally got its first methadone clinic, on South Prospect Street in Burlington. The Chittenden Clinic was opened by the Howard Center, in affiliation with Fletcher Allen Health Care under the medical direction of a doctor named John Brooklyn, who was among the UVM researchers studying buprenorphine.

Brooklyn believes opioid addiction should be treated as the medical condition that it is. "Drug use doesn't define you as an individual," he said. "It doesn't define your morality or anything else but your brain. The difference between you and the person next to you is a few genes in the code." Just as a person with diabetes or heart disease should receive the treatment that has proved to be most efficacious for their particular illness, so should a person with opioid-use disorder.

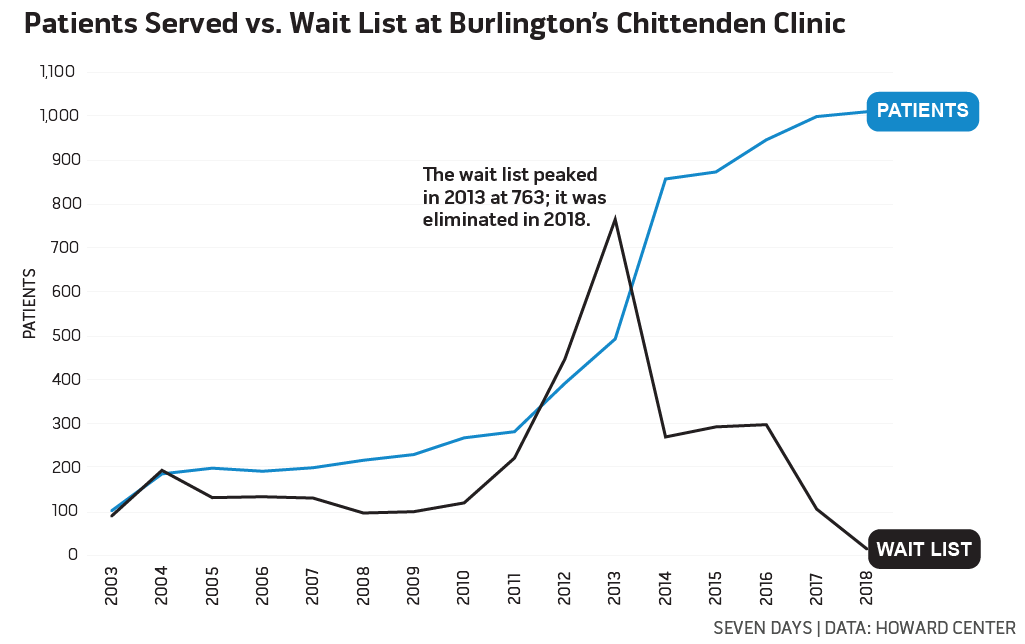

In 2003 the FDA approved buprenorphine, which meant there were now not one but two medications available to treat opioid-use disorder at the Chittenden Clinic: methadone and buprenorphine. Except they weren't available, really. The Chittenden Clinic was authorized to serve just 70 participants and immediately had a wait list.

Unlike methadone, which can only be dispensed for addiction treatment at a federally accredited clinic, any doctor can prescribe buprenorphine — if they get a special "waiver," which requires that they take an eight-hour training. And there are caps on how many patients doctors can prescribe to. This is not the case for any other prescription medication, including opioid-based painkillers.

Further, said Michael Rapaport, medical director at Central Vermont Addiction Medicine, "not many doctors were comfortable managing 'drug addicts' in their practices." He was speaking to me over the phone and wanted to make it clear he disavowed that term, which is considered stigmatizing: "Drug addicts is in air quotes," he said.

There were exceptions, of course. Vermont filmmaker Bess O'Brien made the documentary The Hungry Heart about one of the first doctors in the state to carry a large caseload of buprenorphine patients in private practice: Fred Holmes was a pediatrician in St. Albans who in 2006 began prescribing the medication to young adults, many of whom he had treated as children.

When he was a private-practice physician, Rapaport viewed buprenorphine as an "important tool" he could use when he suspected his patients might be dependent on prescription painkillers. "You don't want to cause conflict" with patients, he said. "Doctors don't go into medicine to ... be a cop." Buprenorphine gave him a way to say, "'This is the fifth or sixth time you've asked to get oxys ... and that's a sign of addiction. I can't continue to do that, but I can offer you Suboxone'" — a brand-name medication that contains buprenorphine, also known as "bupe."

By 2004, the Chittenden Clinic's second full year of operation, Katie was 20 years old, living in Brandon with an abusive boyfriend and facing her first felony charge: grand larceny. She'd barely managed to graduate high school, and her plan to go to college on a softball scholarship had blown up along with her senior year. Holding a job after graduating had been difficult because of her disease, but she and her boyfriend didn't have to pay rent — their landlord was addicted to heroin and crack, so they gave him drugs instead of money.

"It was miserable," she said as we sat on the couch at my apartment. Or I was sitting; Katie was pacing back and forth as she told me how she was already tired of the life she would lead for the next 13 years. But she knew of no way out — if she stopped using heroin, she became sick.

She wasn't aware there were medications that would allow her to get off heroin without going through withdrawal, medications she could take for as long as she needed to prevent cravings and go about building a life around something other than dope. She'd heard of Maple Leaf Farm, a residential rehab located in Underhill that has since closed, but she thought it was for people who struggled with alcohol — an aunt with a drinking problem had gone there when Katie was a kid.

Katie was sick in bed, listening to the Los Lonely Boys song "Heaven" and thinking she had to get out. She had to get the fuck out. And then it came to her: She would go to college.

"I just knew it was the best decision of my life," Katie said with a snort. "I'm going to go to college, and everything is going to be great."

That fall Katie enrolled at Green Mountain College in Poultney. But higher ed didn't stop her from being dopesick, of course, so she continued to use, and though she avoided classes, she did show up for basketball practice.

"You can play basketball on heroin?" I asked.

"No, Kate, you cannot," she said in a deep, matter-of-fact voice, as if we were coanchors of the nightly news. "You think you can, until you start running and end up throwing up in a trash can."

We could laugh about it as we hung out on a wintry January afternoon in a cozy apartment in downtown Burlington. Katie was safe and warm. She had been sober for two years. But there were 15 years between when she was kicked off her college basketball team and that afternoon. Years during which she, like thousands of other people in the state who could not access treatment, cycled in and out of rehab and jail and sobriety, stole from and lied to and alienated the people who love her, was beaten up and raped, contracted hepatitis C and OD'd.

What if the hospital in Rutland, the city closest to where Katie lived, offered methadone to patients in the area who suffered from opioid-use disorder? What if, when a concerned coach tried to get Katie help in 2004, there had been options besides an overnight detox at a facility in Burlington followed by a short-term, abstinence-based residential program that Katie quit after a week?

What if?

What if from the beginning we'd all just listened to Tom Dalton?

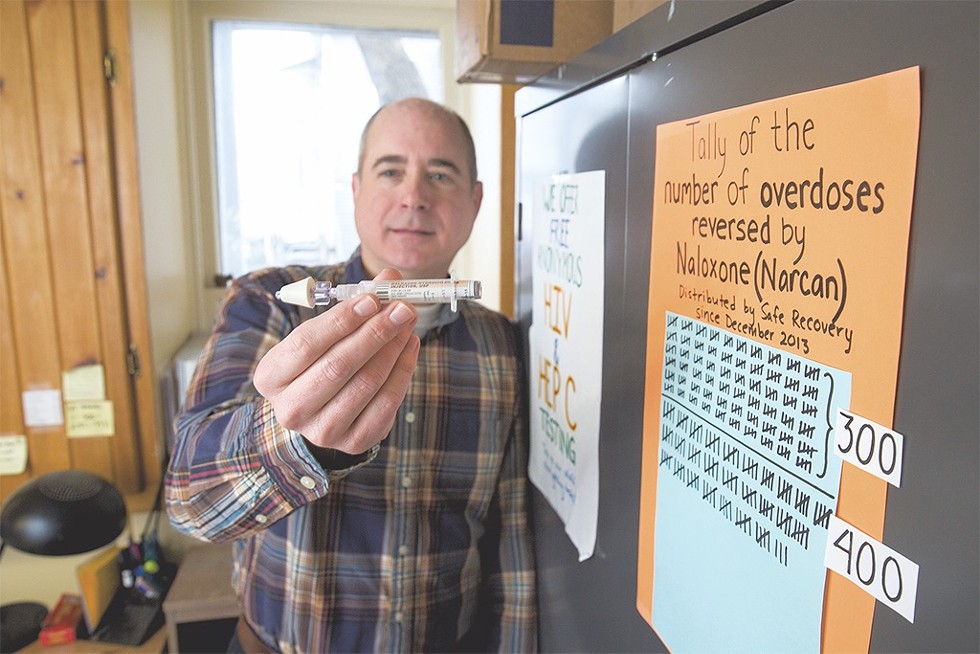

Dalton is the guy who in 2001 opened the state's first syringe exchange in Burlington. Safe Recovery — which, like the Chittenden Clinic, is a program of the Howard Center — not only provides clean needles to injection drug users but also helps them find housing and employment and navigate the legal system.

He's the one who pushed for years to make the opioid-overdose-reversing drug naloxone widely available.

He's the one who lobbied for a Good Samaritan law that would exempt people who call 9-1-1 to report overdoses from prosecution for drug possession.

He's the one who advocated for a doctor to offer on-demand buprenorphine prescriptions out of Safe Recovery to make the medicine as accessible as possible to as many people as possible.

He's the one who put a bug in the ear of the Chittenden County state's attorney about decriminalizing possession of nonprescription buprenorphine, so that the many people who use the drug instead of heroin but can't get to a clinic don't have to choose between taking their medication and getting arrested.

He's the one who nagged the UVM Medical Center Emergency Department to refer overdose patients to the needle exchange.

He's the one who lobbied to make medication-assisted treatment (MAT), as buprenorphine and methadone are called, available to everyone with opioid-use disorder in the state correctional system.

Tom Dalton knew two decades ago that Vermont had an opioid problem, and for almost 20 years he's been doing something about it.

That Tom Dalton.

"Since I was about 22, I was trying to stay sober," Katie said. "But I couldn't stop. I couldn't fucking stop. No matter what the consequences would be, I had no way to stop."

But she did stop for a while in 2006. After a stint at an abstinence-based residential rehab facility, Katie moved to Lebanon, N.H., got a job with a cleaning service and then at a motel.

"Were you on MAT?" I asked, and she told me no one was back then. Only pregnant women could get it, or people who had a doctor who would prescribe it. At the Alcoholics Anonymous meetings she attended, people said MAT was "dirty."

Katie started writing letters to J., a friend of a friend who was incarcerated in Windsor. Soon Katie was visiting J. twice a week. After about six months J. was released, and she and Katie moved into an apartment in Burlington. Things were good for a while — J.'s 6-year-old daughter would come stay with them, they had a nice place to live, they were sober — but according to Katie, "The best part of our relationship was when she was in jail."

When they relapsed, it wasn't because they'd sought out drugs — someone brought over a bag and they got high. For the next couple of years Katie continued to try not to use, but she couldn't access treatment.

"The waiting list at the clinic was ridiculous," she said of the Chittenden Clinic. Sometimes she would buy buprenorphine illegally, but at $30 a pill it was more expensive on the street than heroin. For a while she drove from Burlington back to Lebanon, where she found a doctor who would prescribe her Suboxone. She had to pay out of pocket, but the doctor would give her however much she wanted, and she would sell some of her pills to cover the cost. Ultimately, however, "having to drive that far to get medication became part of the insanity," she said. It was easier to just use heroin.

She and J. would visit Safe Recovery to get clean needles, and Katie would go on her own sometimes just to talk to Elizabeth Gilman-Better and Grace Keller, two staff members. "It was the only place I felt normal," said Katie. "There is no judgment there. None. You never walk into the needle exchange feeling like you're doing something wrong."

In the rest of Katie's life, however, things were going terribly wrong. "J. and I used to deal drugs there," Katie said. Instead of pacing, she was now leaning out the apartment window to smoke; she gestured with her cigarette across the snow-covered roofs to a house on nearby King Street.

Katie and J. went from dealing cocaine to support their habit to ripping off cabdrivers. J. was abusive, one time dragging Katie down a flight of stairs. There were other stories that Katie couldn't bring herself to tell me in person, so instead she texted them to me later. Reading about what happened to her, I wondered at the things we humans do to each other, and what we can survive.

The trauma she had experienced, both growing up and as an adult, was "exploding," she said. At one point she OD'd nine times in less than two months.

"I just wanted to be gone," she said. "I was trying to die, and I was not fucking succeeding."

J. was eventually arrested and charged with robbing a cabdriver, and later Katie was, too. Her first bid in prison lasted more than a year.

But life inside was a relief from the streets, and there was a routine to it she enjoyed: "I got up early, around 6, took a shower, went to chow, started gathering laundry from different units, worked all day, and when I didn't work I went outside and laid in the sun."

"It's the COs [correctional officers] who make it horrible," Katie said. The female inmates were like "sweet candy to the COs. There's a lot of power and control: If you do this for me, I'll bring you this little ChapStick. It starts with ChapStick first, always, I swear. And then it's some hand sanitizer, good-smelling stuff that you can put in conditioner and make it lotion. It's just dumb shit. And then it's bupe."

Drugs, she said, were rampant in jail, both delivered by the COs and smuggled in by prisoners. "There's kind of like a don't-ask-don't-tell policy everywhere you go."

But if the COs made life difficult, the women in jail became her family. "They were the ones who fed me when I was hungry," she said. "When I was detoxing, they took care of me."

That bond itself became a problem, she said. When she was released and struggling on the outside, it "became easier to go back home to my family" in jail.

Treatment options were still essentially nonexistent when Katie was released after that first bid in 2011. She went multiple times to Valley Vista, a residential program in Bradford, only to find herself unable to access medication-assisted treatment upon her release. She was usually high within a day.

"Relapsing is terrible," Katie said. "The worst thing ever. You let everyone down, and guilt overtakes your soul that you just did it again."

At Safe Recovery, Tom Dalton said more than 90 percent of clients talked to him about wanting treatment. "I quickly came to realize that not only do they want treatment, they've had treatment. They've been to Maple Leaf Farm three times; they've been to outpatient treatment. It's not that they don't want treatment, or even that they haven't tried treatment, it's that the treatment has been ineffective."

Why doesn't she just quit? I used to wonder about my sister, for years misunderstanding that it was not a matter of willpower. My sister had what the National Institute on Drug Abuse calls a "chronic, relapsing disease," an illness that "goes beyond physical dependence and is characterized by uncontrollable drug-seeking, no matter the consequences. ... Once a person has heroin use disorder, seeking and using the drug becomes their primary purpose in life."

Katie echoed that description: "When I want to use, it's overpowering. Nothing in this world is as strong as that. They say God is, but I have a hard time believing it, because anytime I want to get high, my addiction decides to before I do. It's a horrible place to be."

It takes the average person with opioid-use disorder eight years and four to five attempts at treatment to stay sober for one year, according to John Kelly, a Harvard Medical School professor and researcher. Ample evidence indicates that MAT is the most effective treatment.

Between 2002 and 2013, five MAT clinics, or hubs, as they're called, opened across the state, from Brattleboro to central Vermont to the Northeast Kingdom. In 2013, a hub finally opened in Rutland, which was no longer looking so pristine after being ravaged for a decade and a half by the epidemic that did not go away when local doctors launched a NIMBY campaign against methadone.

But hubs could only accept so many patients: In 2013 the wait list at the Chittenden Clinic reached 763 people. The way the state approached it, former health commissioner Chen explained, was to say: "'We have this much money, this is how many individuals can go to the hub, and we capped it. We're done. We've spent what we can on this problem.'"

"We didn't provide [treatment] to scale fast enough," said Dalton, who, after 17 years at Safe Recovery, left to become executive director of Vermonters for Criminal Justice Reform. "A lot of bad things were happening to people ... and we tolerated those waiting lists for many, many years."

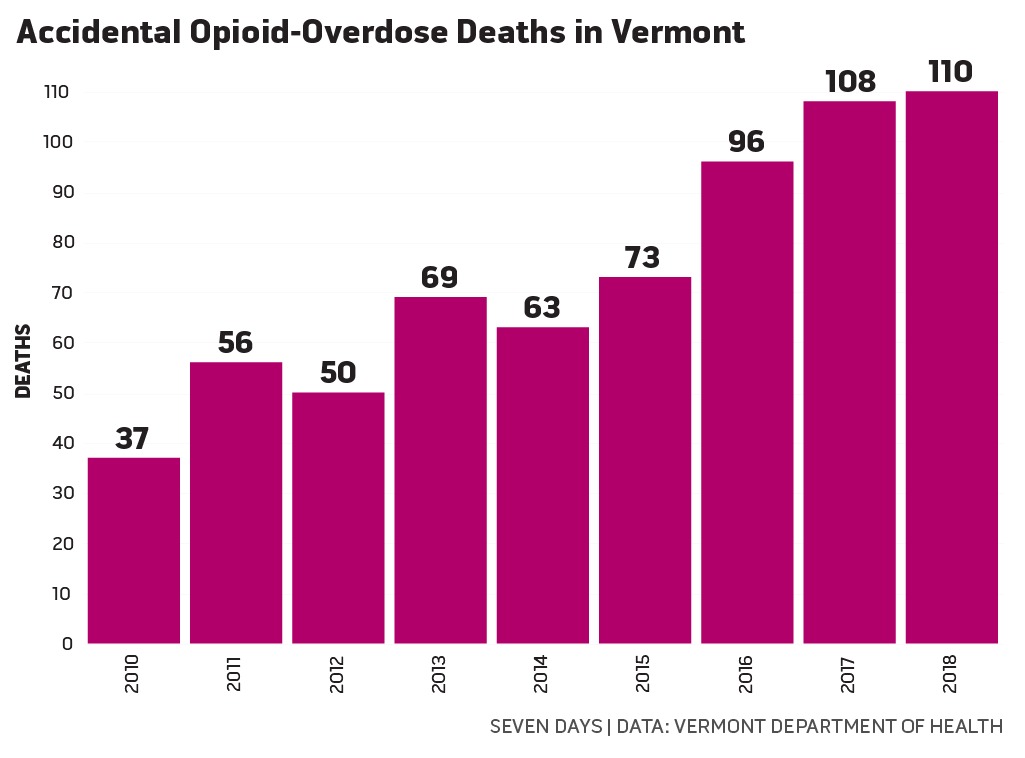

In 2011, the year Peter Shumlin was elected governor, a record 56 Vermonters died from opioid-related overdoses. Tens of thousands more were suffering from addiction. No one was marching on the Statehouse to demand a solution, but families were whispering in the new governor's ear, telling him what was happening to their sons and daughters, their mothers and fathers, their sisters and brothers and cousins.

In his new role as health commissioner, Chen noticed in 2013 that, for the first time ever, there were more individuals seeking treatment for opioids than alcohol in the state. "Oh," he said to himself. "Something really is going on."

When he reached out to Shumlin's office to discuss this data point, he was told that the governor was planning to dedicate his entire State of the State address to the opioid epidemic; instead of working on a press release about the treatment stat, Chen started helping Shumlin prepare his speech.

"In every corner of our state, heroin and opiate drug addiction threatens us," Shumlin announced on January 8, 2014. "It threatens the safety that has always blessed our state ... It requires all of us to take action before the quality of life that we cherish so much is compromised."

While it may have been a turning point, a political act heralded as "brave" and "bold," Shumlin's speech did not mark the beginning of the end.

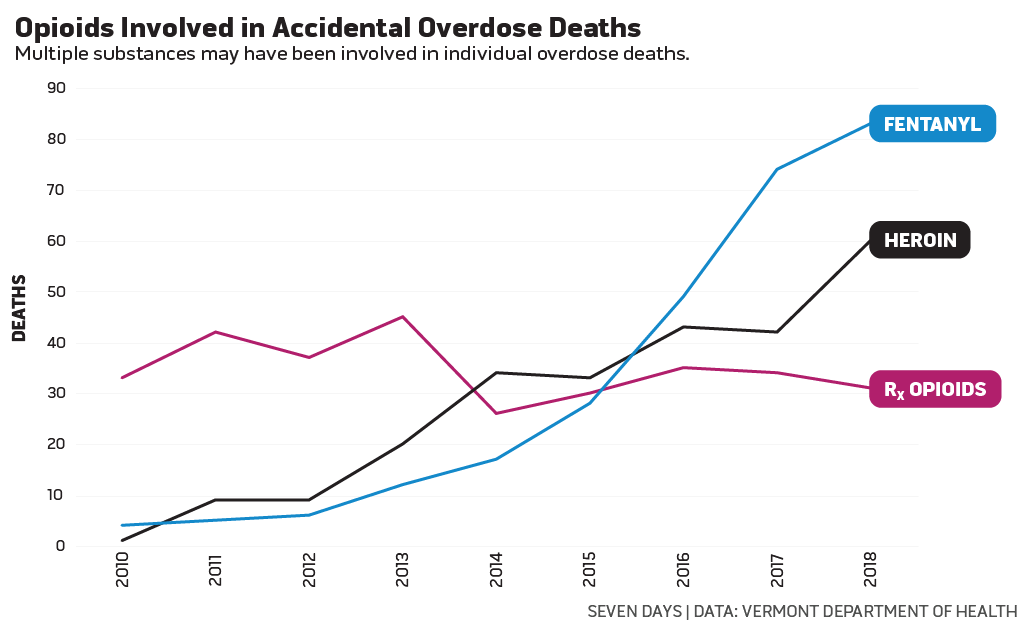

That year, the opioid-overdose death rate dropped, only to spike 16 percent in 2015 and another 32 percent in 2016, due largely to an influx of fentanyl, a synthetic opioid used to cut heroin that is up to 50 times more potent. Over the course of one 2016 weekend, nine people overdosed in Barre, one fatally, on heroin that investigators believed was laced with fentanyl. In Brattleboro in 2017, 11 people overdosed within a single 24-hour period. In 2018, opioid-overdose deaths in Vermont reached 110, setting a record high for the fifth year in a row. The UVM Medical Center kicked off 2019 by treating seven overdoses on one January night.

As Shumlin and Chen worked on their speech, Katie and a guy she knew walked into a small Burlington convenience store. The man stood in the doorway while Katie took four candy bars from a shelf — she was high and hadn't eaten for days. At the counter, instead of paying she demanded money and threatened to shoot the cashier if she didn't comply, but the cashier didn't take her seriously until the man Katie was with started shouting. Katie took the money the cashier handed her and peeled back the wrapper of a candy bar on her way out.

Katie was arrested and charged with assault and robbery. Returning to jail, she said, was a relief; she was going home.

Before her sentencing, a judge allowed her to attend Valley Vista, the same residential treatment program she'd been to numerous times before. While she was there she learned that her grandmother was dying of cancer, and for Katie this was, if not her bottom, the beginning of a long, slow end. Or the beginning of the beginning.

"Her dying wish was for me to be happy and to live a sober life," Katie said, which was both a gift and, as she put it, a hard pill to swallow. "How do I do that when I've never done it before?"

It took a while, but Vermont has been doing what it had never done before. Shumlin's address lit a fire under state government: The Vermont Department of Health issued rules in 2015 and 2017 that restrict doctors' prescribing practices for opioid-based painkillers.

In 2016 Chen issued a standing order for naloxone that allows every pharmacy in the state to dispense it so that, as Chen put it, the opioid-overdose-reversing drug would be "available like soda water."

And perhaps most importantly, the state expanded medication-assisted treatment. Chen and his colleagues developed a strategy that allowed the state to remove the caps on the number of people MAT hubs could treat, and by 2017 the waiting lists had been eliminated. Almost two decades after Vermont noticed it had an opioid problem, treatment is available to anyone who can make it to a clinic.

Currently, 8,500 people receive MAT in Vermont, 1.6 percent of the adult population. This is more people per capita than in any other state.

All Vermont prisoners with opioid-use disorder incarcerated in state facilities are eligible to receive MAT.

In the past two years, a Chittenden County coalition led by Burlington Mayor Miro Weinberger has launched numerous measures to fight the epidemic that are groundbreaking not just in the state but in the country, and those efforts are showing great promise: The number of opioid-overdose deaths in the county dropped 50 percent in 2018, even as the number of fatalities statewide went up.

Last September, Vermont Attorney General T.J. Donovan filed a lawsuit against the makers of OxyContin.

State Rep. Selene Colburn (P/D-Burlington) introduced legislation earlier this month that would decriminalize possession of non-prescribed buprenorphine statewide.

"We don't give up on people," said the Howard Center's Bob Bick, who helped open the Chittenden Clinic in 2002. "The seminal message is: We don't give up."

On November 27, 2017, Katie was released from prison for the last time. She'd spent the past three years trying to honor her grandmother's dying wish, but parole violations, homelessness and relapse kept landing her back in jail, where she would detox from either illicit drugs or the methadone or buprenorphine she'd been prescribed to help her stay off them.

This time she was determined to stay sober and out of jail, but detoxing from methadone and buprenorphine is painful — far worse, she said, than coming off heroin. She was on parole, which meant that even a minor screwup could land her back inside, so she didn't plan to go back on MAT for fear that she would once again have to detox in prison.

On her second day out, she ran into Grace Keller, now program coordinator at Safe Recovery, who asked if she was on MAT.

"I was like, 'No, I'm not, I don't want to go through all that again. I can't take detoxing anymore,'" Katie said.

Related Opioid Addiction: A Glossary of Common Terms

Opioid Addiction: A Glossary of Common Terms

By Kate O'Neill

Opioid Crisis

Safe Recovery operates on the harm-reduction model, which means it offers people who are in active drug use ways to stay safe and other support, without requiring or even advocating for treatment. But Keller gently encouraged Katie to get on something, tearing up as she told her, "'In the past six months, I've lost more clients than in the entire 10 years I've worked at Safe Recovery.'" The next day Katie called and made an appointment at the Chittenden Clinic.

Around the same time, she was ordered to go to an intensive outpatient program where she participated in dialectical behavioral therapy, which teaches patients specific skills to help manage emotions and conflict. "I threw a fit like a child that I had to go," Katie said, "but truly I was blessed that they made me."

She credits DBT with making her more aware of her thinking, which in turn helped her stay calm and not react in situations that triggered her. She started to understand herself and her addiction in a new way and began voluntarily seeing a therapist to address the trauma that at different points had contributed to her desire to use drugs.

On January 17, 2019, Katie celebrated two years of sobriety, the longest stretch since she took that first pill at 15. She still struggles with the requirements of parole and the hoops she has to jump through at the Chittenden Clinic, and she's having difficulty finding a job. But she's stayed on buprenorphine and has her own apartment, and when she's stressed out, she heads to the Dollar General to buy supplies for an art project instead of to a dealer to score heroin.

"Crafting is my coping skill," she said with an eye roll.

Like my sister, I was 16 years old the first time I fell in love. It was late at night and the hospital room was dark but for the light that drifted in from the hall, and there she was, sleeping in a bassinet next to my mom's bed: Maddie.

In spite of the fact that I was a teenager who loved to sleep and my sister was an infant who kept the house awake with her crying, I was smitten. "I love you a bushel and a peck, a bushel and a peck and a hug around the neck," I would sing when she cried, swaying back and forth as I held her in my arms — and, as if I'd cast a spell, she would fall asleep, burrowing her head into my shoulder. Sometimes during those first few months she would sleep on my chest as I sang, her head tucked beneath my chin, and I would match my breath to hers as she slept, our chests rising and falling in time. When she was there, I wanted her to stay forever.

"We have 10 more minutes," I told her 24 years later, as visiting hours wrapped up at one of the many rehabs she went to for help. "How do you want to spend it?"

"Hugging," she said, and sat in my lap, wrapping her arms around my neck and burrowing her head into my shoulder. Would that she had stayed there forever.

Need Help?

If you or someone you love are suffering from opioid use disorder and need treatment and support resources, here's how to get connected:

- In Vermont: Call 2-1-1, a free and confidential resource hotline provided by the United Way of Vermont.

- Outside Vermont: Call 1-800-662-HELP, a free, confidential 24-hour hotline run by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

"Hooked: Stories and Solutions From Vermont's Opioid Epidemic" is made possible in part by funding from the Vermont Community Foundation, the University of Vermont Health Network and Pomerleau Real Estate. The series is reported and edited by Seven Days news staff; underwriters have no influence on the content.

Have a tip or a story to share about opioid addiction in Vermont?

Email our news editors at [email protected] or call 802-864-5684.

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

Tags: Opioid Crisis, Hooked, opioid epidemic, addiction

About The Author

Kate O'Neill

Bio:

In “Hooked: Stories and Solutions from Vermont’s Opioid Crisis,” writer Kate O’Neill explores the state’s opioid epidemic and efforts to address it using traditional journalism, narrative storytelling and her own experiences. Her sister, Madelyn Linsenmeir, died in October 2018 after years battling opioid addiction.

In “Hooked: Stories and Solutions from Vermont’s Opioid Crisis,” writer Kate O’Neill explores the state’s opioid epidemic and efforts to address it using traditional journalism, narrative storytelling and her own experiences. Her sister, Madelyn Linsenmeir, died in October 2018 after years battling opioid addiction.

More By This Author

Latest in Category

Speaking of...

-

Burlington Has Surpassed Last Year's OD Tally — and It's Only August

Aug 4, 2023 -

Vermont's Relapse: Efforts to Address Opioid Addiction Were Starting to Work. Then Potent New Street Drugs Arrived.

Jun 14, 2023 -

A Recovery Center in Johnson Is Helping Reinvigorate the Town

Dec 14, 2022 -

Meth Use Is Growing Around Burlington — and Could Portend More Problems for Vermont

Oct 12, 2022 -

Brenda Siegel Brings the Experience of Poverty to Her Campaign for Governor

Sep 14, 2022 - More »

find, follow, fan us: