Published April 30, 2008 at 8:40 a.m.

At Passover, celebrants read the Haggadah, which tells the story of the Jews’ slavery under the Egyptian Pharaoh and their Exodus out of his land. They’re in such a hurry that they don’t even let the bread rise — hence, matzoh. The cliffhanger comes when they’re standing with their toes in the Red Sea, Pharoah’s army is galloping behind them, everybody is kvetching to Moses — “What, there weren’t enough graves in Egypt that you had to shlep us all the way out here to die?” — and, just in time, God parts the waves to let the Chosen People pass, then closes the sea over the pursuing bad guys. Very Indiana Jones.

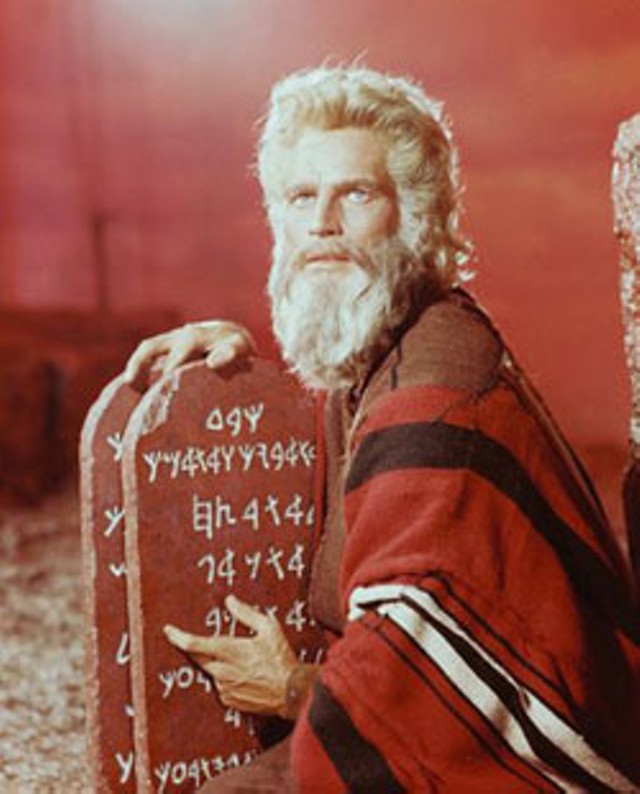

After this harrowing escape, the Jews meander to Mount Sinai to pick up the Ten Commandments. Then they spend 40 years wandering around the desert, eating manna and trying to figure out how to get to the Promised Land.

Forty years have passed since 1968, that breathless year when it felt as if the waves had parted and we’d arrived on the other shore. Our seder group has been celebrating Passover almost that long — 30 years, give or take a few. Every year we’ve asked the traditional questions: What does this old story have to do with us? What is slavery? What is liberation? How can we end slavery and spread liberation around?

This year we agreed that present-day slavery could be read in the photograph on the front page of The New York Times of a Haitian child in a dirty pink dress standing atop a garbage heap, searching for food. The accompanying article reported that rising fuel and food prices are depriving the world’s poor of even the staples — wheat, rice and corn.

Meanwhile, the Pharoahs are fat and happy. According to other Times articles in the same week, hedge fund traders are cashing in on the mortgage crisis (George Soros ended last year $3 billion richer), and the still exceedingly wealthy are building chateaux and flying their friends around in private jets for weekends of revelry.

The Promised Land appears farther away than ever. At our seder table, we admitted to feeling enraged — and also depressed, overwhelmed, even paralyzed.

I’ve been thinking a lot about why progressive activism feels so hard these days. If your aim is to change the big stuff — in this case, the inequities of global capitalism — you may feel that you’re doing nothing to better people’s lives right now. You want to improve that Haitian child’s lot — so you send money to some relief fund. Then you wonder if the only life you’re improving is your own. You’ve momentarily assuaged your guilt, but gotten no closer to changing the big stuff.

If we frame it another way, however, there may be a way out of the conundrum.

Many younger activists — Gen Xers and Millennials — avoid this stuck feeling by not sweating the big stuff. As one Gen-Xer told Time magazine, “We don’t want to change things. We want to fix things.”

So, if Boomer red-greens — socialist environmentalists — believe they have to overthrow capitalism to end global warming, because global warming is a result of capitalism’s intrinsic need to grow, many younger greens believe that capitalism, and the creativity it fosters, will solve global warming.

The young build windmills — and scoff at their elders for chasing windmills. At a discussion of cross-generational organizing I recently participated in, Kim Fellner, a Boomer and lifelong community and union organizer, quoted a Gen-Xer who dismissed the century-long struggle for socialism: The Soviet Union is dead, he told Kim. “Why waste your time” trying to overthrow the one economic system that’s got any resiliency?

To which the writer Alix Kates Shulman responded that maybe the fault lines aren’t formed so much by age as by an embrace — or a rejection — of utopianism (whose name, for the ’60s generation, was socialism).

Rinku Sen, 40, executive director of the racial justice think tank Applied Research Center, concurred. She’s not a socialist, she said. ARC doesn’t even call itself “leftist” — not because it isn’t, but “because it doesn’t mean anything to our people.” Unwilling to wait around for — or believe in — the Revolution, Rin is especially interested in “public-private” collaborations and in projects where people can “take our demands directly to the corporations.” Both, she feels, can make a social and economic difference now.

Rinku told us about an organization of immigrants that is eliminating the profiteers in the massive capital transfers between immigrants working in wealthy countries and their families back home. The new scheme has immigrants holding on to the remittances that ordinarily go to companies like Western Union and pooling them. The “Million Dollar Club” — on average, 350 immigrants — decides how to invest the money. Their funds will be managed by “socially responsible” businesspeople.

Another private-public hybrid is the community benefits agreement (CBA), a contract between grassroots organizations, often composed of poor people of color, and developers coming into their neighborhoods. The locals try to get guarantees of jobs, affordable housing and public transportation or other environmentally rational infrastructures from the developers. The developers, who need community board clearances and permits, use the CBA to show they have local support. The only government involvement might be the contracts law that governs the agreements. Indeed, some are only unenforceable side letters of intention.

The efforts of young fixers are often accompanied by the rhetoric that people can be trusted more than the government. The remittances project is a direct redistribution of wealth, bypassing the state. The CBA is supposedly a redistribution of power, again sans state intervention. What they actually demonstrate, however, is confidence in free enterprise, if not in the big corporation, then in small businesses such as the guy running the remittances fund — or those it will invest in. A question immediately arises: What about democracy? Who makes the decisions — voters or CEOs? Who enforces them? At our discussion, Rinku was quick to say she and ARC aren’t anti-government — they’re for regulation and state-sponsored redistribution of wealth through progressive taxation.

But can power be gotten with fixes, and without the consolidating mechanisms of government? If those fixes depend on the largesse of private business, I’m skeptical. It’s got to be a heady feeling for the local community organizer to sit across the table, negotiating a deal with a billion-dollar developer. But what happens when the developer backs out of the CBA?

That’s what is happening with Atlantic Yards, a $4 billion, 22-acre complex in Brooklyn, including a basketball stadium, a Frank Gehry office tower complex, and luxury housing. After initial united opposition from the neighborhoods, some dubiously representative community groups peeled off and signed a CBA with the developer, who promised that 50 percent of the housing would be “affordable” (at prices unaffordable to people with the borough’s median incomes). Now the recession is scaling back the project; housing is postponed until further notice. Local officials are on their knees asking for a moratorium on demolishing houses that won’t be replaced with new apartments.

The City of Burlington is in a similar situation with the developer of the new Courtyard Marriott on Battery Street. The company has reneged on part of the original plan, to build 13 affordable housing units. By law, the Westlake Development Project must contribute money to the city’s Housing Trust Fund to compensate for the housing it’s not building. By law, builders of new projects must include either affordable or “inclusionary” housing or pay into the fund, and the city has recently increased the mandatory per-unit contribution. That’s the way to go: Get a law. Still, across the country, community and social-justice groups are finding that it is up to them to hold developers accountable, even when statute requires corporate responsibility.

Frustration with utopian visions — and with the state — almost always ends in smaller local fixes. “Take our demands directly to the corporation” was the cry of the anti-globalization movement 10 years ago. Desiring to pass over the nation-state, which they viewed as a weak, docile servant of capital, anti-globalizers proposed in its place a vaguely organized grassroots control and redistribution of the resources.

When that idea turned out to be too big and idealistic to manage, much anti-globalization energy found its way to the creation and defense of local economies: small businesses making artisanal cheese and neighbors eating it. Now, I’m a big fan of the local bleu cheese being made in my Northeast Kingdom neighborhood. But meanwhile, global industrial agriculture is running the show. And, in part because of it, the Haitian child is starving.

I could go on. But I’m not here to dis fixes — because, heaven knows, we need plenty of them. Equally important, when they work, they not only solve an immediate problem but also supply the emotional element without which any organizing effort founders: optimism, the by-product of tangible results. They’re just not enough.

Fixers also need a vision of where they’re going. It might not be the same one as their parents’ — but they need one. Because without a vision, you never know whether your fixes are moving you forward or backward. If your vision is a world with minimal growth, the CBA that enables the mega-development, even if it’s tossing a few jobs or homes off the top of the tower, is counterproductive. Tangible results, moreover, should not be mistaken for power; they just mean you solved a problem for your adversary. As soon as you become the problem, you’re expendable — selling hotdogs at the stadium or working as a chambermaid at the Marriott, and living an hour away.

In the end, fixers and changers need not be in conflict. They may simply have different temperaments, and these may be generational. All that self-esteem building at school and positive reinforcement at home may have made the children of the Boomers more content. They don’t hate authority as much as their elders do. Unlike their parents, they don’t want to kill their parents. At the same time, they are members of a numerically smaller generation facing much larger problems. So they’re both confident in their abilities to accomplish something and humbler about what they can accomplish. As for capitalism, they don’t want to burn down the house they were born in; they’d like to renovate it — with recycled materials and flea market furniture, and good taste, of course.

But there’s one thing everyone can learn from the old — and I mean really old. During those 40 years in the desert, the Jews weren’t just building sand castles. They were consolidating themselves as a people — envisioning the Promised Land and committing themselves to a set of shared principles, a kind of map to get there. The Ten Commandments are a utopian document if ever there was one. Maybe they weren’t the best at practical action (“How many Jews does it take to screw in a lightbulb?”), but they were building a movement. Projects, one by one, don’t empower. Movements do.

So here’s a proposal: Changers and fixers, let’s start a coalition. Meeting place TBA. Manna and beverages will be served.

More By This Author

Speaking of...

-

Bernie Sanders Sits Down With 'Seven Days' to Talk About Aging Vermont

Apr 3, 2024 -

The Over-60 Crowd Steps Up With Bill McKibben's Climate Action Group Third Act

Mar 29, 2023 -

A Youth-Activism Camp in Marshfield Stands Up to a Zoning Complaint From the Town

Feb 1, 2023 -

Al Franken Blends Satire and Political Commentary at Flynn Show

Sep 19, 2022 -

Candidates for Governor Display Stark Differences at Tunbridge Fair Debate

Sep 16, 2022 - More »

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.