Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

-

Education

Scott Official Pushes Back on Former State…

-

News

Burlington Budget Deficit Balloons to $13.1 Million

-

Education

Senate Committee Votes 3-2 to Recommend Saunders…

- Court Rejects Roxbury's Request to Block School Budget Vote Education 0

- Norwich University Names New President Education 0

- Media Note: Mitch Wertlieb Named Host of 'Vermont This Week' Health Care 0

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

Published May 14, 2014 at 9:00 a.m. | Updated October 8, 2020 at 5:35 p.m.

Melanie Peyser was a teenager when her father, Fred, insisted she work a booth at the Addison County Fair and Field Days. Her job? Handing out leaflets and playing a VHS tape on a loop portraying footage of gas pipeline explosions.

"It was mortifying," recalled Peyser, now 46; she just wanted to hit the midway.

"I wasn't mortified!" her 79-year-old mother, Selina Peyser, chimed in. "I handed out leaflets. I stood there. My husband worked incredibly hard."

Fred Peyser was instrumental in blocking an underground pipeline proposed in the 1980s to bring natural gas into New England from Canada. It would have cut through the Peysers' property in Monkton and stretched some 340 miles through Vermont. "Someday it may serve as a business-school case study: How Not to Win Friends While Trying to Build a Pipeline," Susan Levine wrote in a 1989 Philadelphia Inquirer story about the conflict. "To be subtitled, of course: Why Even Having the Governor on Your Side Doesn't Always Help."

Sound familiar?

History is repeating itself at the Peyser house. This winter, nearly three decades after the last pipeline project, Selina Peyser found herself fielding phone calls from a representative of the Canadian-owned utility Vermont Gas Systems.

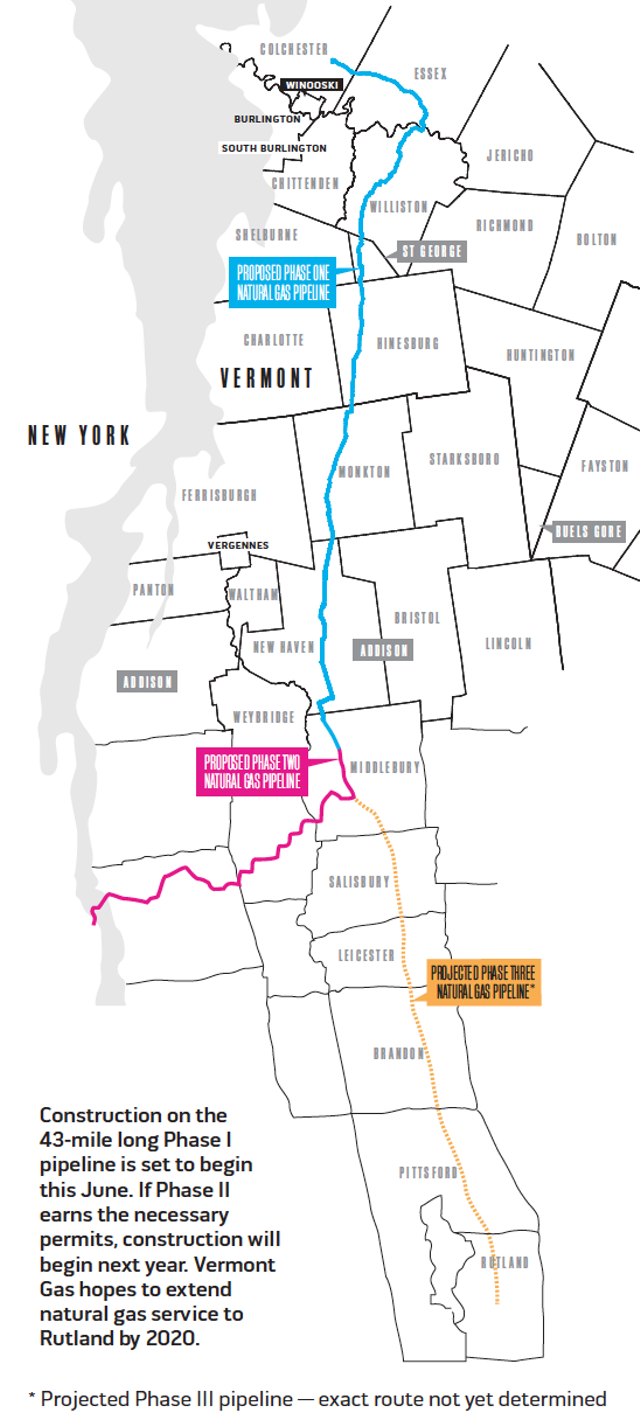

Turned out, the Peyser property was in the path of a new pipeline — this one the 43-mile Addison-Rutland Natural Gas transmission line, which earned a stamp of approval from Vermont's Public Service Board in late December. The pipeline will cut through 222 parcels on its journey from Chittenden County to Middlebury — the first leg of a distribution network Vermont Gas hopes to extend as far south as Rutland.

In a telephone message, a "land agent" — tasked with brokering a deal that would allow Vermont Gas to cross her property — warned Peyser he needed to hear from her soon or Vermont Gas would begin legal proceedings. Just a few days later, Peyser received a letter threatening eminent domain, the process by which the government seizes private land for public use while providing "just compensation."

Melanie Peyser, the once-reluctant activist, was living in California. During a visit to Vermont in December, she saw what was happening to her mother. Her father, who'd handled the couple's legal affairs, died in 2008.

"I basically quit my job," said Peyser, who moved home in March. And "even for me," said Peyser, who holds a law degree, the easement agreements and paperwork and right-of-way details constituted a labyrinthine mess. "I find it frankly confusing," she said. But helping her mother — and protecting what she sees as her father's legacy — spurred Melanie Peyser on.

"This is not just an environmental issue, or a financial issue," said Melanie Peyser. "This is a justice issue."

Over coffee in the sunny sitting room at the Peysers' stately Monkton home, the two women spoke about their dealings with Vermont Gas — Selina Peyser growing agitated, her daughter calming her. "Mom, don't be so angry," Melanie urged her mother.

"It's incredibly stressful," said Selina Peyser. "I don't like to be threatened."

A 'Comedy of Errors'

Frustration with Vermont Gas has been bubbling up in homes and communities all along the proposed pipeline — which was divided into two phases for the purposes of obtaining permits. As the company's land agents hash out deals along the Phase I route, the Public Service Board is considering Vermont Gas' application to build Phase II.

That leg would jog south and west from Middlebury, through the towns of Cornwall and Shoreham, and then under Lake Champlain. The goal is to deliver gas to the International Paper mill in Ticonderoga. IP has promised not only to cover the entire cost of the second leg, but to help subsidize building a bigger transmission line from Chittenden County. Altogether, IP is poised to chip in $70 million. Vermont Gas argues that the money will allow the company to extend service farther still — to Rutland County — by 2020. Without IP's contribution, the company contends, service to Rutland wouldn't be viable until 2035 — "if ever," said spokesman Steve Wark.

That's proving to be a tough sell in Addison County, where the proposal touches hot-button topics: The environment. Fracking. Property rights. And the pitch hasn't been made easier, critics say, by a series of missteps on the part of Vermont Gas.

Critics allege a pattern of bad behavior: Surveyors who trespassed, or misrepresented their affiliation with Vermont Gas; land agents who portrayed themselves as "mediators" or brokers rather than employees of the gas company; company officials who left questions about easements unanswered for months; a corporation that pushed for an aggressive schedule in Public Service Board proceedings, leaving landowners and some town officials feeling frantic, rushed and overwhelmed. Some tell stories of land agents literally dangling checks in front of landowners in an effort to win "easements" that would grant Vermont Gas permission to use a landowner's property without purchasing it outright.

Just look at how the company handled a statement made by CEO Don Gilbert, who publicly said of the pipeline, "We won't come if people don't want us." In response to discovery questions submitted as part of the PSB process, the company backpedaled; Gilbert was referring to distribution services, not the transmission pipeline itself, Vermont Gas contended.

"If I were watching from the sidelines as a management consultant, I would say this is a comedy of errors," said Bruce Hiland, the chair of the Cornwall selectboard. Hiland doesn't live along the proposed route, but he and fellow selectmen have been vocal in their opposition to the project — spurred on, Hiland said, by polls that revealed Cornwall opposes the pipeline by a ratio of 3-to-1.

"I can't tell whether it's incompetence or arrogance or both," said Raph Worrick, a Cornwall resident whose property is in the line of fire.

Notably, it's not just pipeline opponents who are chiding the gas company for what many agree was a flawed rollout of the pipeline proposal.

"It does certainly sound to me like it has not been handled as well as it could have been," said Robin Scheu, the executive director of the Addison County Economic Development Corporation — a supporter of the pipeline on the grounds that natural gas will provide a competitive advantage to Addison County businesses. "If they had to do it again, I would guess that they would do it a bit differently," she said of Vermont Gas.

Kevin Ellis, a partner in Monpelier-based PR firm Ellis Mills, agreed.

"Well, you know something is wrong when a couple of days before Town Meeting, they send out a letter to various landowners threatening to take their land by eminent domain," said Ellis. "Those kinds of errors are not fatal, but they illustrate a large misunderstanding of what it takes to get it done in Vermont."

The PSB, in its December approval of Phase I, noted that Vermont Gas "has frankly acknowledged that such misconduct occurred," and while the board praised the company's candor as a "first step" toward restoring trust, it urged utilities to be "sensitive to the dignity of Vermonters and to respect their rights."

Apologies are falling on the deaf ears of pipeline opponents, who accuse Vermont Gas of begging for forgiveness rather than asking for permission.

"Unfortunately, it's awfully easy to lose trust, and not so easy to get it back," said Worrick.

Jump-Starting the Opposition

Wark admits that Vermont Gas didn't expect to face such vehement opposition in Addison County. After all, Vermonters, by and large, greeted natural gas with open arms in the 1960s, when Vermont Gas extended its first pipelines carrying fuel from the Canadian border. Instead of angry op-eds, newspapers then ran glowing explainer pieces about the benefits and safety of natural gas, alongside exuberant advertisements welcoming Vermont Gas to the state.

In the decades since, Wark said, customers have been happy. Their ranks have swelled to roughly 50,000 customers in Franklin and Chittenden counties, where underground pipelines serve 17 communities.

But Addison County isn't the Vermont of five decades ago. Residents have become more wary of large utility projects, according to Wark, as a result of problems stemming from the 2005 Northwest Reliability Project upgrades to Vermont Electric Company transmission lines.

And Vermonters of 1965 didn't have the internet.

"These people in Shoreham and Monkton, they're on the web at night," said Ellis. "They're googling pipeline explosions. They understand tar sands. They know where this gas is coming from. Thirty years ago, 40 years ago, people had no idea."

The voices of a few angry landowners became a chorus. Initially "I wasn't up in arms about it," said Worrick — but after dealing with his land agent, he said the situation started to feel "fishy."

Down the road, Randy and Mary Martin acknowledged that they, too, were unlikely activists. "Our kids are shocked," said Randy Martin. "We used to think climate change was a bunch of hooey invented by Al Gore."

Word spread. Environmentalists joined the effort; many pointed to the hypocrisy of building a pipeline to carry fracked gas in a state that had, in 2012, banned hydraulic fracturing. In the process of drilling underground for gas and oil, chemical-laden water is pumped at high pressure into shale formations. In other parts of the country, the mining technique has been blamed for contaminating water supplies.

Vermont Gas admits that a portion of the gas it pumps through its pipelines is fracked, but can't say exactly how much. As for complaints about misbehavior on the part of land agents, Wark conceded that Vermont Gas didn't staff up sufficiently to go door-to-door and handle all the easement negotiations.

So they hired contractors. The right-of-way agents weren't always "prepared to provide the service level we expected," said Wark.

"Let's face it," he said. "With any major project there are going to be issues. Are there people that are angry? Absolutely. Are there people that are quite satisfied? Yes."

"There are times when people don't get it right," said Wark of the contractors and land agents — but he added that Vermont Gas is bringing many of those jobs back in house: The company added 14 positions last year and plan to hire another 10 people in the coming months.

That's too late for the Addison County landowners who've already had bad encounters.

- Aaron Shrewsbury

Real estate agent Maren Vasatka found out that her property fell on the Phase I route by accident: Driving home past the Monkton firehouse, she saw a notice on the reader board for a meeting that evening with Vermont Gas. Intrigued, she went to the meeting, where she said a Vermont Gas official told the residents that the company had reached out to every affected landowner. A surveyor had spoken with her a few months earlier, but when she'd asked directly if her home was on the proposed route, the man told her that the route hadn't yet been finalized.

"Two neighbors were sitting right in front of us," Vasatka said. "I leaned forward to my two neighbors and said, 'Has anyone talked to you?'" Their answer was the same as Vasatka's: "No."

Now, as Vasatka hashes out the details of a roughly 600-foot easement with the company, her frustration continues.

"There were lots of questions that we had about the project," she said. She and her partner put them to representatives from the gas company: Would there be blasting on the property? How much workspace would the company need during construction? What would be stored on site? The answers, Vasatka said, were always: "We don't know."

"Sometimes ... one representative would say one thing, and one rep would say something entirely different," said Vasatka. As recently as last week, after a three-hour meeting with Vermont Gas, Vasatka still didn't have all the information she sought.

Vasatka said that Vermont Gas initially offered her $2,500 for her easement. Now, after negotiations, it's up to $42,500. Good for her, she notes, but not necessarily for those along the pipeline route who may lack the skills or resources to negotiate.

"What if someone doesn't know to ask questions?" asked Melanie Peyser, who is particularly concerned about other senior citizens in the area. She wants to see the PSB set up a fair easement negotiation fund; ultimately, she said, landowners can't rely on the goodness of a corporation to arrive at equitable deals.

In response to complaints that Vermont Gas' low initial offers have been unfair, Wark said that the easement agreements aren't blank checks.

"It's meant to make people whole, not rich, because at the end of the day, ratepayers are picking up the tab," he said.

Pros and Cons

With the PSB Certificate of Public Good in hand, Vermont Gas is getting the final permits to break ground on Phase I of its pipeline in June; it has secured options (the precursors to easements) or full agreements for half of the 222 parcels along the Phase I corridor. Meanwhile, it's moving ahead to secure the same stamp of approval for Phase II.

There are plenty of pros to recommend transitioning to natural gas. Vergennes residents voted 345-to-143 in a nonbinding vote in favor of the project. The Addison County Regional Planning Commission endorsed both phases of the project for complying with the regional plan. Large Phase I customers will include Agri-Mark, the producer of Cabot cheese, which has a large facility in Middlebury; Middlebury College; Porter Medical Center; and many others. Cabot alone anticipates saving as much as $3 million per year on fuel costs at their plant.

"It levels the playing field for us, for businesses that are thinking about, 'Do I want to be in Chittenden County or Addison County?'" said Addison County Development Corporation's Scheu.

"The benefits of this project are just too big to pass up," said Wark.

Try telling that to the angry, frustrated Vermonters who showed up at the Shoreham Elementary School cafeteria on May 7 to urge the PSB to deny a permit for Phase II.

Many cradled signs or wore stickers with the slogan, "Stop the Fracked Gas Pipeline." Banners and placards — "Friends Don't Let Friends Build Frack Pipes" alongside the school's "Got Milk?" advertisements — competed for real estate on the walls.

One after another, opponents stood up to voice their concerns and questions. Would horizontal drilling under Lake Champlain dislodge toxic sludge on the lake bottom? What about the possible damage to the lake's ecosystem? What about the possibility of explosions or accidents along the route itself?

Others argued that investing millions in a pipeline to carry fossil fuel was an irresponsible choice for Vermont at a time when the state, they said, should be aggressively pursuing renewable energy. That's the position adopted by the Vermont Public Interest Research Group, which is an "intervenor" in the PSB process. That means it will provide testimony and participate in evidentiary hearings.

"By moving forward in this massive investment in fossil fuel infrastructure, we will discourage safer, more sustainable alternatives," said VPIRG executive director Paul Burns in an interview with Seven Days after the May 7 hearing.

Still others at the meeting railed against a project that would only provide limited distribution in Shoreham and Cornwall; the vast majority of the gas carried by the pipeline would be bound for International Paper.

"It's our land, it's our orchards, it's our sugarbush, it's our deer yards," said Cornwall resident Stan Grzyb. "We are being threatened by these two corporations in taking our land for the profit of those two businesses, and we resent it."

"I don't understand why a board that's meant to be representing Vermont is considering something that's purely for the benefit of a Canadian corporation and a New York corporation," said Timothy Fisher, a Cornwall artist, who returned to his seat and buried his head in his hands.

Anger brewed in pockets of people within the crowd. They muttered and shook their heads when representatives from Rutland and the New York side of Lake Champlain stood up to speak to the merits of the project, and the importance of natural gas service for International Paper. Even the handful of Vermont residents who spoke in favor of the project — citing a reduction in emissions at the Ticonderoga mill, and the economic benefits to Shoreham's village — faced heckling.

"Some of us in Shoreham have homes less than half a mile from the lake," said Nick Causton. "We live, breathe and sleep with the mill. We even hear the 7 a.m. wake-up call." Causton supported the pipeline on the basis that natural gas would mean a drastic cut in greenhouse-gas emissions at the IP plant and better air quality for Vermonters on the other side of the lake.

But comments against the project far outnumbered those in support of it. A few landowners from Phase I spoke out — among them Jane Palmer, who hissed at the PSB, "I guess democracy can be bought after all. It's for the money and by the money." Voices from the crowd swelled around her, and together they chanted, "We are the people. We are the many. We don't want this pipeline."

"There's a certain level of disrespect for people who support the project, and I don't know where that's coming from," said Wark after the hearing.

Supporters just don't turn out for public hearings, Wark said — in part, he believes, because of the harsh reaction they face.

"We can't lose sight of the fact that while there is a vocal opposition, they are a minority," said Wark. "People come out generally to oppose or complain about something. They don't come out to support it."

Notably, intervenors — including landowners on the proposed route in Cornwall and Shoreham — didn't speak at the May 7 public hearing; the PSB process prevents them from doing so.

Worrick falls in that category, so he watched from the back of the Shoreham auditorium as others testified. He's representing himself in the PSB hearings. Earlier in the week, surrounded by stacks of paper at his kitchen table, he spoke of how taxing and time-consuming the process has been. He's spending at least 20 hours a week preparing documents, filing discovery questions and reading past PSB dockets to prepare for the proceedings.

Vermont Gas is seeking a roughly 3,500-foot easement on his 135-acre property in Cornwall, which he inherited from his parents. Worrick worries about how the pipeline will affect the value of his property, particularly if he chooses to subdivide in the future.

But his concerns go beyond property values.

"A big part of my issue is that the way they've behaved on this doesn't make me trust them," said Worrick, a carpenter and musician. "There's just sort of an arrogance that, 'We've decided to do this, we're going to come through here, and if you don't like it, we're going to make you roll over.'"

He said that right-of-way agents misrepresented themselves in early dealings with him, claiming they didn't work for Vermont Gas and instead were "brokers." Down the road, Randy and Mary Martin had similar complaints; land agents showed up at their door in November 2012, asking the couple for rights to survey their land. They said they were told to "keep this to yourself."

Like Worrick, the Martins said they've turned over countless hours to represent themselves in the PSB process; a lawyer just isn't financially feasible for either family.

"We don't have that kind of money," said Randy Martin, who runs an insurance agency with his wife out of their home on Route 74.

A Tale of Two Counties

Perhaps looking for a warmer welcome, Vermont Gas kicked off a series of three open houses in Rutland County late last month, setting up camp for an evening at Rutland High School to tout the benefits of natural gas. They're billing the project as "Phase III" and hope to ferry gas to Rutland by 2020.

That's been the goal all along. In Rutland, economic development officials hope cheaper fuel could entice new businesses and retain existing ones. Reaching out early — and often — could theoretically help Vermont Gas avoid some of the turmoil they've faced in Addison County.

And so 20-odd Vermont Gas employees trekked from their South Burlington headquarters to Rutland in late April. The blue shirts — Vermont Gas employees — vastly outnumbered the few visitors who trickled in. Employees manned tables outfitted with placards reading "About Natural Gas," "Safety" and "How much can I $ave?" A few were stationed by the door, ready to greet visitors.

"We're hoping to promote a little bit of excitement," said one. Nearby, a large poster promised: "We stand ready to serve you with 24/7 service!"

Plenty in Rutland are already excited about natural gas. Among them is Tom DePoy, a local businessman who stopped by the open house to bolster the turnout.

"I know Rutland needs clean, efficient fuel for both the homes and the businesses, and this seems like a good prospect," said DePoy, who was chatting with Tom Donahue, the executive vice president and CEO of the Rutland Region Chamber of Commerce.

"We, Rutland, we can't sit back and wait," said Donahue, ticking through examples of recent manufacturing job losses in Vermont. "We want to help our businesses."

Some themes cropped up repeatedly among the few visitors. Several mentioned the long winter and the high price of heating fuel. Vermont Gas officials, in turn, talked up the cheap price of natural gas: By switching, a Vermonter who burns 1,000 gallons of fuel oil at the current price of roughly $3.90 a gallon would save just shy of $2,000 a year. Many spoke wistfully of the infrastructure already in place to the east of them. "They have the interstate, they have the rail, they have the bus service," said Donahue.

The subtext: Give us the pipeline.

But Phase III won't get built before Phase II, and opponents are optimistic that they could still block the Ticonderoga-bound pipe. They contend the "public good" that prevailed in the first phase isn't as obvious in the case of the second, because its biggest beneficiary is a New York corporation.

"I think we have a shot," said Worrick. "I think they've shot themselves in the foot so many times that they're a little wounded."

Vermont Gas doesn't agree. If the company earns its permits for Phase II, construction could begin next year.

"When projects are done, the rancor starts to subside," said Wark. "Frankly, I think in two years, this will be long forgotten."

Ellis is more realistic: "It hurts you in the long run," he said of companies that view their PSB permits as "a trump card." "What you want in 10 years is for those people to say, 'OK, we fought, we lost, but at least the company respected us and listened to us.'"

Related Stories

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

Tags: Environment, Vermont Gas, natural gas, fracking, pipeline, Addison County

More By This Author

About The Author

Kathryn Flagg

Bio:

Kathryn Flagg was a Seven Days staff writer from 2012 through 2015. She completed a fellowship in environmental journalism at Middlebury College, and her work has also appeared in the Addison County Independent, Wyoming Public Radio and Orion Magazine.

Kathryn Flagg was a Seven Days staff writer from 2012 through 2015. She completed a fellowship in environmental journalism at Middlebury College, and her work has also appeared in the Addison County Independent, Wyoming Public Radio and Orion Magazine.

Speaking of...

-

Addison County State's Attorney Vekos Pleads Not Guilty to Driving Under Influence

Feb 12, 2024 -

Court Upholds Vermont Gas' Purchase of Methane From a New York Landfill

Jan 12, 2024 -

Hundreds Gather in Vergennes to Protest Anti-Trans Speaker

Jun 20, 2023 -

Regulators Are Poised to Let Vermont Gas Buy Methane From a Distant Landfill

Oct 21, 2022 -

Hot Air? Vermont Gas Says It’s Reinventing Itself to Help the Climate. Critics Call Its Strategy ‘Greenwashing.’

Jul 27, 2022 - More »

Comments (8)

Showing 1-8 of 8

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.

- 1. Scott Official Pushes Back on Former State Board of Ed Chair's Testimony Education

- 2. Burlington Budget Deficit Balloons to $13.1 Million News

- 3. Legislature Advances Measures to Improve Vermont’s Response to Animal Cruelty Politics

- 4. Home Is Where the Target Is: Suburban SoBu Builds a Downtown Neighborhood Real Estate

- 5. Senate Committee Votes 3-2 to Recommend Saunders as Education Secretary Education

- 6. A Former MMA Fighter Runs a Wildlife Rehabilitation Center in Cabot News

- 7. Vermont Rep. Emilie Kornheiser Sees Raising Revenue as Part of Her Mission Politics

- 1. Totally Transfixed: A Rare Eclipse on a Bluebird Day Dazzled Crowds in Northern Vermont 2024 Solar Eclipse

- 2. Zoie Saunders, Gov. Scott’s Pick for Education Secretary, Faces Questions About Her Qualifications Education

- 3. Don't Trash Those Solar Eclipse Glasses! Groups Collect Them to Be Reused 2024 Solar Eclipse

- 4. State Will Build Secure Juvenile Treatment Center in Vergennes News

- 5. Vermont Awarded $62 Million in Federal Solar Incentives News

- 6. Queen of the City: Mulvaney-Stanak Sworn In as Burlington Mayor News

- 7. New Jersey Earthquake Is Felt in Vermont News