Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

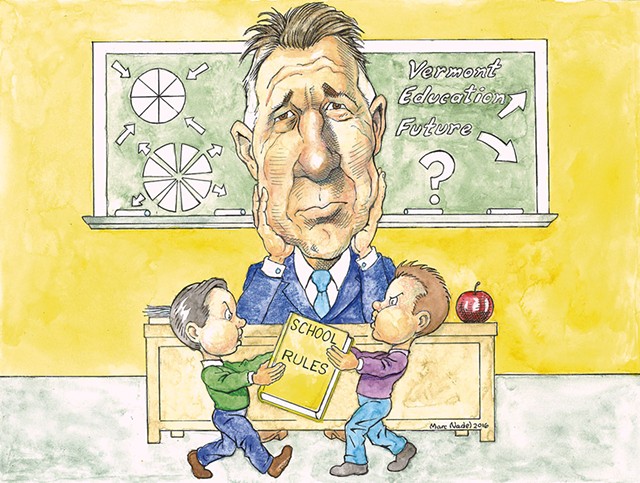

New Rules: Dispute Spotlights How Vermont's Education Policy Is Set

Published December 14, 2016 at 10:00 a.m.

A week before last month's election, gubernatorial candidate Phil Scott decried the State Board of Education's plan to step up regulation of Vermont's independent schools. It was an uncharacteristically sharp — and specific — statement coming from the controversy-averse politician.

Now governor-elect Scott is taking office at a key moment in the debate over the proposed rules, which some contend could have a drastic impact on academic institutions such as the Thaddeus Stevens School, the Sharon Academy and Stratton Mountain School. But to get his way, Scott has to navigate an unusual power-sharing arrangement.

One of its quirks: The governor handpicks his entire cabinet, except for his education secretary, whom he must choose in collaboration with the education board.

Until 2013, the governor appointed the nine voting members of the education board, and they selected the state's top education executive.

That changed three years ago when the state legislature passed a bill empowering the governor to pick the ed secretary, with one caveat: He has to choose from the candidates put forward by the ed board.

The board retained its "rulemaking authority," which in theory works like this: The legislature writes policy; the board drafts rules to put those policies into practice; and then the agency, which reports to both the board and the governor, makes sure those rules are implemented.

In other words, the thankless task of hashing out the details falls to members of the ed board. They include former speaker of the House Stephan Morse, former school superintendent Bill Mathis, former state representative Peter Peltz, and Stacy Weinberger, an early education administrator who's married to Burlington Mayor Miro Weinberger.

By most accounts, the unconventional arrangement has been working quite well. But in recent months, the drab conference rooms where the board convenes have seen plenty of political drama.

The board is busy revising the requirements for private independent schools in- and out-of-state that receive public tuition money. Since 1869, Vermont has allowed towns without schools of their own to pay tuition — usually the state average — for students to go elsewhere. Roughly half of the 5,400 students taking advantage of school choice attend private schools in Vermont, including Thetford Academy, Burr and Burton Academy, and the Long Trail School. The new rules would require those schools to adopt open-enrollment policies and be prepared to provide all types of special education. They'd also have to disclose financial information to the state.

The proposed changes have generated vehement pushback from independent schools and communities that cherish school choice. Parents are concerned that the new rules could effectively end school choice for some towns, by forcing independent schools to close their doors to publicly funded students. Mill Moore, executive director of the Vermont Independent Schools Association, said the requirements would be "costly," "intrusive" and "potentially quite damaging" to the schools he represents. Independent school headmasters have emphasized that the modifications would impose a one-size-fits-all approach to schools that prosper precisely because they cater to particular needs.

Other groups counter that private schools shouldn't be able to turn away anyone. Doing so deprives young people of educational opportunities and strains public schools, which end up serving the neediest students in a state with a shrinking population, forcing the per-pupil cost up.

"We need to ensure that the system we're using to educate kids isn't either intentionally or unintentionally dividing students by class or disability," said Nicole Mace, executive director of the Vermont School Boards Association.

Despite the controversy, the education board voted unanimously to approve the new rules, passing them on for a review by the Interagency Committee on Administrative Rules — a governor-selected group chaired by the secretary of administration. To the ed board's surprise, Gov. Peter Shumlin's ICAR rejected them, asking for more analysis and public input.

On November 1, one week before the election, Scott joined the fray, calling on the board to scrap its proposed rules, which, he said, "could undermine, or eliminate, school choice in communities where it has existed for over 100 years. They could also weaken both our educational ecosystem and our economy at a time we need to be strengthening them for our kids and for our economic future."

Morse claims the outcry is unwarranted: "I don't get it. I don't see why these updated rules are so controversial," he said. On November 29, he announced several draft rule clarifications and changes, which appear to have calmed both sides. Among the tweaks: Independent schools won't have to follow all federal and state regulations that apply to public schools, only those addressing health and safety. Schools must have a school nurse and counseling services, among other resources. Regarding safety, the buildings need to meet certain architectural and fire standards, etc., and schools have to have plans in place to respond to student "misbehavior."

Many citizens had negative reactions at two recent meetings in Manchester and St. Johnsbury.

After the board finalizes the rules, which could happen on December 20, it will send them back to ICAR and, if approved, on to the Legislative Committee on Administrative Rules. Neither committee decides on the merits of the changes; rather, they determine whether the board has followed the proper procedure and adhered to legislative intent. The public will be able to weigh in again before LCAR makes a decision.

Surprisingly, the governor has no formal say in the matter, beyond picking replacements for Morse and vice chair Sean-Marie Oller, whose six-year terms end on February 28. He's already said he will appoint people "who are open-minded about school choice and value the role it can play in growing our economy and retaining and recruiting more working-age families."

The seven remaining members voted for the proposed rules that Scott denounced. They form a majority on the board charged with fielding potential secretary candidates. If Scott doesn't like their recommendations, all he can do is ask for more names.

Secretary Rebecca Holcombe is likely to be among Scott's options. The former principal and teacher has led the agency since January 2014, presiding over an escalating debate about shrinking enrollment and rising school costs. Holcombe confirmed to Seven Days that she wants to keep her job.

She wouldn't agree to an interview, so it's unclear where she stands on the debate about independent schools. Spokeswoman Haley Dover said the agency isn't supposed to weigh in. "We're kind of the middleman, because we work for the board and the governor," she explained.

So far, Holcombe seems to have handled the go-between role deftly. "Rebecca Holcombe is just incredible," Morse said. "The board has worked really closely with her."

Scott's spokesman, Ethan Latour, also complimented Holcombe, saying she's "done a great job." The board expects to submit its candidates by January 17, and Scott has set March 1 as the start date for his appointee.

A pair of Democratic senators could prove useful allies to the Republican governor. Bennington County seatmates Dick Sears and Brian Campion announced plans last week to introduce a bill that would strip the ed board of its rulemaking authority and give the governor full power to pick the education secretary.

Sears said his constituents are worried that the board's proposed rule changes will endanger Burr and Burton Academy. He suggested the rules are so significant that they amount to legislation and that "members of an appointed board that are serving for six-year terms shouldn't be writing legislation." As evidence that the board has overstepped its bounds, Sears noted that the legislature itself previously considered, but ultimately did not pursue, additional requirements for independent schools.

"I think, historically, the board and the agency have worked well together," said Rep. Oliver Olsen (I-Londonderry), who serves on the Burr and Burton board. "But if we get into a situation where the administration has a different vision than the board has, there's going to be potential for conflict, and this is a good example."

Olsen also pointed out that the board will soon have an even bigger role to play in education policy: Act 46 charges it with developing merger plans for the school districts that don't do so on their own. "That's a messy business," he said.

Sen. Ann Cummings (D-Washington), who chaired the Senate Education Committee last session, is amenable to looking at other ways of making education policy. "It may well be the time to have a discussion about what is the balance of power." She observed, "You have some pretty strong personalities on that board, and they have some very definite opinions."

Rep. David Sharpe (D-Bristol), who chairs the House Education Committee, doesn't think lawmakers should interfere with the board's duties. "I am very reluctant to make education more political than it already is," he said. "It's the reason we have a state board with independent authority. My hope is it could be resolved in that process, and we don't bring it into the legislature and make it a political football."

As for the proposed independent-school rule changes, Scott told reporters Monday that he remains concerned. His spokesman offered an open-ended response to the Bennington senators' planned bill: "The governor-elect obviously thinks it's an interesting proposal but would like to hear more feedback from legislators and other stakeholders."

Related Stories

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

Tags: Education, Independent schools, education regulation, Phil Scoot, independent school regulation, education secretary, Rebecca Holcombe

More By This Author

About The Author

Alicia Freese

Bio:

Alicia Freese was a Seven Days staff writer from 2014 through 2018.

Alicia Freese was a Seven Days staff writer from 2014 through 2018.

Speaking of...

-

Approved Religious Schools Are Eligible for Public Dollars, VT Education Secretary Says

Sep 14, 2022 -

A Vermont Drug Company's Failure to Maintain Standards Led to Recalls — and Its Demise

Jun 22, 2022 -

Rebecca Holcombe to Run for Vermont House Seat

May 23, 2022 -

Scott Vetoes Gun Bill, Offers Compromise to Close 'Charleston Loophole'

Feb 22, 2022 -

Zuckerman to Face Scott in Governor's Race, Gray Upsets Ashe for LG

Aug 11, 2020 - More »

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.

- 1. UVM, Middlebury College Students Set Up Encampments to Protest War in Gaza News

- 2. Dog Hiking Challenge Pushes Humans to Explore Vermont With Their Pups True 802

- 3. Scott Official Pushes Back on Former State Board of Ed Chair's Testimony Education

- 4. A Former MMA Fighter Runs a Wildlife Rehabilitation Center in Cabot News

- 5. Burlington Budget Deficit Balloons to $13.1 Million News

- 6. Senate Committee Votes 3-2 to Recommend Saunders as Education Secretary Education

- 7. Home Is Where the Target Is: Suburban SoBu Builds a Downtown Neighborhood Real Estate

- 1. Totally Transfixed: A Rare Eclipse on a Bluebird Day Dazzled Crowds in Northern Vermont 2024 Solar Eclipse

- 2. Zoie Saunders, Gov. Scott’s Pick for Education Secretary, Faces Questions About Her Qualifications Education

- 3. Don't Trash Those Solar Eclipse Glasses! Groups Collect Them to Be Reused 2024 Solar Eclipse

- 4. State Will Build Secure Juvenile Treatment Center in Vergennes News

- 5. Vermont Awarded $62 Million in Federal Solar Incentives News

- 6. Queen of the City: Mulvaney-Stanak Sworn In as Burlington Mayor News

- 7. New Jersey Earthquake Is Felt in Vermont News