Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

-

Education

Scott Official Pushes Back on Former State…

-

News

Burlington Budget Deficit Balloons to $13.1 Million

-

Education

Senate Committee Votes 3-2 to Recommend Saunders…

- Court Rejects Roxbury's Request to Block School Budget Vote Education 0

- Norwich University Names New President Education 0

- Media Note: Mitch Wertlieb Named Host of 'Vermont This Week' Health Care 0

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

Pass or Fail? Newly Branded Vermont State University Needs More Students — but Its Enrollment Is Declining

Published August 16, 2023 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated August 18, 2023 at 6:15 p.m.

A July tour for prospective students at Vermont State University's Lyndon campus drew precisely one: Trinitie Simonds — and she already had been accepted at the school. The Lyndonville teen and her father were outnumbered by employees of the state colleges system on hand to answer her questions.

And that wasn't the only sparsely attended July tour on the campuses of the 6-week-old Vermont State University, which is made up of former state colleges in Lyndon, Johnson, Randolph and Castleton. The next day, an introduction to the Johnson campus drew six potential students. A tour of the Randolph campus on August 5 had three. A parent in the latter group commented that she'd seen several tours with about two dozen people just days before at the much larger University of Vermont.

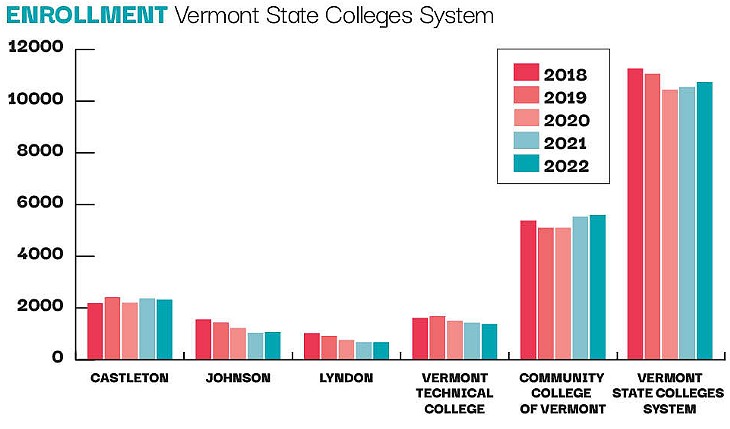

The low turnout is a troubling bellwether for the university, which, with the Community College of Vermont, makes up the Vermont State Colleges System. With budgets in the red, years of enrollment decline, underused buildings and recent crises to overcome, the university needs a surge of students if it's going to survive with all of its campuses intact.

Yet figures from early August show a steep decline in enrollment for the fall term: nearly 20 percent fewer students than the 5,400 served last year by the campuses that make up the new university.

The shortage of students highlights the dire state of the school's finances. This year, the state colleges system expects to run a $17 million deficit on an operating budget of $134 million. That shortfall will be made up by an infusion of additional funds that began arriving from the state in 2021. But that aid is temporary and scheduled to drop sharply over the next three years. Administrators must find millions in spending cuts and new revenue — primarily by attracting new students — to get the system in the black before the extra state aid runs out.

There are those who doubt that every campus can be saved, including a former chancellor of the state colleges system, who called for closing some of the campuses three years ago. Gov. Phil Scott recently raised a similar possibility if the money problems aren't solved.

"It's not going to be an easy process," said Sen. Jane Kitchel (D-Caledonia), who, as chair of the Senate Appropriations Committee, has watched the state colleges struggle to gain solvency. "It's going to take some strong leadership."

In the face of these challenges, Vermont State University's interim president, Mike Smith, projects resolute faith in the system's ability to survive and thrive.

He notes that pandemic lockdowns are receding into history and believes that more traditional-age students will venture back to campuses. He is counting on a bright future for online and hybrid learning — and for early college programs that bring high schoolers to campus, the only area of strong enrollment growth at the university this year.

Further, he said, he expects the colleges to find millions in savings by increasing class sizes, reducing duplication of services and adding seats in popular career-oriented programs such as nursing.

Eager to assure would-be applicants that all is well, Smith struck an upbeat note, saying, "I'm confident that if we have a strategic plan, with targets along the way for admissions, that we can find the money."

Study Local

The former state colleges go back a long way. Castleton's roots date to a primary school founded in 1787 and a 19th-century medical college. Most of the campuses started as teachers' colleges, or "normal" schools, designed to serve a rural population. They evolved through the years to meet the needs of Vermont's changing economy, broadening their 20th-century offerings to include liberal arts education. In the early 1960s, they joined a newly created Vermont State Colleges System.

The schools have always served a role distinct from that of UVM, a large research-based institution with higher tuition. In addition to producing teachers, the colleges traditionally provided technical and agricultural training, mostly to Vermont students — many the first in their families to attend college — who sought career-focused majors and wanted to stay close to home.

That remains true in many cases. Chris Bachand, father of Trinitie Simonds, the student on the Lyndon tour, said of his daughter's choice of that campus: "A lot of it has to do with class size and proximity to home, and a slow exposure to the great big world out there, as opposed to throwing her to the wolves."

Vermont State University's challenge is that there are simply fewer high school graduates seeking a four-year, on-campus education. The problem begins with the state's birth rate, which started to decline in the 1990s. The number of college-age Vermonters is still falling. By 2030, there will be 20 percent fewer 15- to 19-year-olds than there were in 2010, the state projects. The numbers for the rest of northern New England and the rural Northeast aren't much different.

click to enlarge

- Josh Kuckens

- Trinitie Simonds (left) on a tour of Vermont State University's Lyndon campus with her father, Chris Bachand

While educators and policy makers in the past urged Vermonters to acquire some kind of postsecondary education, the reality is that most jobs in the state — three-quarters of them, according to the Vermont Futures Project, an economic research group — don't require a college degree.

College is sometimes promoted as a default option for teens who don't have a post-high school plan, said Mary Anne Sheahan, executive director of the business-sponsored Vermont Talent Pipeline. "Now we have all these college-educated people who are working in Lowe's and Starbucks because they can't find a job at their level in what they want to do," she said.

These strains already have contributed to the closing of half a dozen private liberal arts schools in Vermont, most recently Marlboro College and Green Mountain College in Poultney.

For that reason, some adults now recommend that teens explore the trades through internships, apprenticeships and on-the-job training programs. Young people who do choose higher education aren't all looking for a traditional on-campus experience.

"When we go out and promote college, people sometimes look at us as if, You're just marketing to me," Marti Kingsley said. She's a counselor in the Northeast Kingdom for the Vermont Student Assistance Corporation, a nonprofit that administers financial aid. "[They say], 'I can't go into debt. My friend has done this, and their life has been ruined.'"

These trends — along with the pandemic — helped drive down enrollment by a third at Lyndon and Johnson between 2018 and 2022. At Vermont Technical College, the number of students dropped by 11 percent. Among the residential campuses, only Castleton saw an increase, of 6 percent. In contrast, the Community College of Vermont, where many students study part time while working, saw gains of 4 percent.

Better Call Mike

On top of changing demographics and aspirations, the state colleges system — and its new university incarnation — have suffered public relations disasters in this decade that have damaged confidence in the system.

In spring 2020, then-chancellor Jeb Spaulding responded to the state colleges' financial crisis by recommending that the system close three of its four residential campuses, in Lyndon, Johnson and Randolph.

An outcry ensued. That plan was shelved, and Spaulding resigned.

Lawmakers responded with a powerful financial boost: a pledge of $200 million in temporary assistance to help keep the system afloat while it reorganized to solve its money problems. In 2021, they raised the colleges' annual appropriation from $30 million to about $48 million now.

Meanwhile, a 2020 report from the legislature's Select Committee on the Future of Public Higher Education in Vermont called for urgent — and possibly painful — action to reduce costs and make the colleges more affordable to Vermonters.

"It is no longer possible for this can to be kicked further down the road," the report stated.

Vermont had the highest public college tuition in the nation, the report said — and historically low state support that has forced the schools to rely on tuition more than their peers do. It also said the college campuses were underused and had about $55 million in deferred maintenance needs.

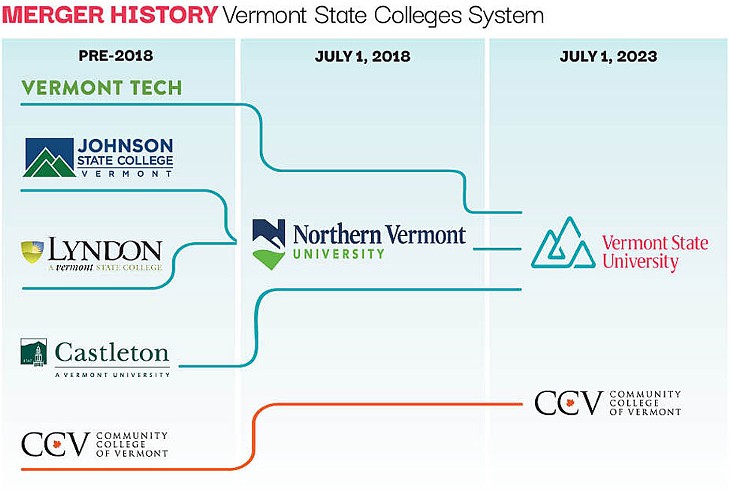

In response, the state colleges system last year announced consolidation of its campuses into the new Vermont State University and hired a president, Parwinder Grewal, to lead it. He had previously guided a public college reorganization in Texas and seemed to be an ideal choice to head up the merger.

In February, Grewal announced the state system's libraries would ditch their books and go all digital. Outraged staff, students and alumni protested so loudly that the spectacle earned national attention. They came down hard on the board of trustees and administrators, painting them as out-of-touch bureaucrats with inflated pay.

Chancellor Sophie Zdatny's $238,000 annual salary came up repeatedly in student protests, public meetings and social media discussions.

Some Vermont lawmakers protested the library plan, too, and sought to stop it. In April, Grewal resigned.

The board asked Smith to serve as interim president. A former U.S. Navy SEAL and later a secretary of administration under Vermont governor Jim Douglas, Smith long ago earned the title of "fixer" for stepping in at troubled institutions. Among other short-time assignments, he led Burlington College in the final months before it closed. One of the first things he did as interim president of Vermont State University was to rescind the library decision.

Smith, who is 69, does not plan to stay long; he says he is firmly committed to retiring in November. While the board searches for a permanent successor, it is seeking a second interim president, who will become the university's third leader in less than a year.

Enrollment Front and Center

Smith acknowledges that the shrinking number of high school graduates makes it more difficult to attract students. He blames publicity about the library proposal for some of the enrollment decline. A simultaneous plan to downgrade the system's sports teams didn't help, either. And simply changing the names of three schools to create VTSU, he said, was going to cause some confusion.

"Whenever you do a name change — or a brand change, as I call it — it's bound to be a distraction," he said.

The continuing decline in student numbers is the biggest threat to the system's bottom line. Tuition, fees, and room and board provide about 35 percent of the budget. Reversing that decline is the new university's top priority.

To try to attract more students, VTSU cut its base tuition about 15 percent this year to just under $10,000 for in-state students and just under $20,000 for others. Before the merger, annual tuition at Castleton was about $13,000; at NVU, about $11,000.

VTSU is also expanding its online ads and college fair attendance into new areas, including Pennsylvania and metro Washington, D.C. With keen competition for students, it's looking for more ways to interest people who have gone straight from school to the workforce.

click to enlarge

- Josh Kuckens

- Trinitie Simonds touring Vermont State University's Lyndon campus with her father, Chris Bachand

Simonds, the student who toured Lyndon, is an example. She graduated from high school in 2021 and worked in retail before deciding to go to college. Her parents live in Lyndonville, and her mom attended Lyndon. Simonds feels safe there after a rocky experience with remote learning during the pandemic, her father said.

Asked for details of other ways the system will attract students, Smith said, as he often does, that VTSU is still working on its strategic plan.

"We have to do a better job of talking to young people and their parents about the importance of higher ed," Smith said.

Smith, a first-generation college student himself, sees hybrid and remote learning as critical to making newly merged academic programs available to students at all of the university's campuses. But that's not an answer for everyone. While many students prefer the convenience of learning online, others say it's more difficult.

"Online doesn't work for so many people," said Kingsley, of VSAC. "Students will come to me saying they can't do online work. It's not structured enough; they're not disciplined enough yet. They get behind from the beginning, and they can't ever really catch up."

VTSU has not set a goal for the size of its student body. "What we are doing is looking for incremental growth," said Maurice Ouimet, vice president for admissions and enrollment services, in early August. "We have a lot of programs that are under-enrolled, and students don't know what these programs are. We need to do a better job of getting that information out."

The Transformation

VTSU administrators say the individual campuses won't lose their character in the merger.

With a strong studio arts program and two art galleries, the former Johnson State College hosts courses for an array of degrees in liberal arts and sciences. The hilly green campus sports several outdoor art installations. Science students work with their professors on regional research, which they say gives them a chance for intensive lab work they wouldn't get at a larger school.

The smaller Lyndon campus has a strong broadcast journalism program that includes News7, an on-campus news studio that covers 14 towns on social media and a college website.

"Today you cannot turn on a radio or television station in Vermont or New England without finding a Lyndon graduate at the microphone, looking into a camera, running a camera, or engineering the equipment necessary to provide communication," senator Joe Benning (R-Caledonia) wrote in an open letter to Gov. Phil Scott in 2020, after Spaulding's proposal to close the Lyndon campus.

Lyndon also draws students to its outdoor education program, music industry major, and well-regarded atmospheric science — or weather and climate change — program, which has been reduced in recent years. Smith made a point of saying he plans to rebuild the meteorology offerings.

That program, and Lyndon's relatively low sticker price, led Bobby Saba, a Mansfield, Mass., native, to choose Lyndon. Saba, who graduated last year, now specializes in tornado research as he works toward a master's degree at the University of Oklahoma.

"You say the word Lyndon, and everyone is like, 'Do you know so-and-so?'" said Saba, 24, of the meteorology field. He added that the broadcast program had also attracted him to the school.

"The hands-on experience I got at the on-campus news station was unmatched," Saba said. "Even in my junior year, I was getting job offers and I didn't even have a degree yet."

Castleton has the university's largest residential population and offers the most typical college experience. Its alumni, students, faculty and staff raised the largest outcry earlier this year after Grewal's announcement about removing the library books.

Castleton's curricula includes political science, nursing, and media and communications, as well as a resort and hospitality management program that offers students opportunities to gain professional experience at Killington Resort.

And the former Vermont Technical College offers an array of career-focused programs, including dental hygiene, forestry and pilot training, in Randolph and at its small campus in Williston.

Signs of rivalry between the campuses emerge when members of the Castleton community talk about the future of the system as a whole. Some faculty and staff say privately that the merger will drain money from the stronger Castleton, which, with more students in dorms, has a more traditional and cohesive college identity. Many believe Castleton wasn't the campus in trouble premerger.

"Lyndon and Johnson are failing. Enrollment is down, and revenue is plummeting," said Jonathan Spiro, a former Castleton president who served as a teacher and dean in his 20 years at the school. Castleton, however, "was actually in decent shape before the merger and is now in crisis," he said.

Not everyone at the school feels that way. Political science professor Rich Clark said the biggest threat he sees to the campus where he has taught for 12 years is not the merger but the new remote learning options. Communicating by camera and microphone detracts from the classroom experience, Clark said, and he'd much rather get to know his students in person.

That said, he plans to stick around.

"I've decided to dig in and make things better, not skedaddle," said Clark, a former nontraditional student who earned his PhD in his thirties. "I just really like teaching, and I love my students."

Accounting 101

Each VTSU campus is beautiful in its own way, offering a small-scale glimpse of the graceful greens and majestic structures that have come to define higher education for generations of Americans. They're used in summer for camps and conferences; Johnson's campus sheltered an array of emergency services after the July floods devastated the small town.

But the campuses cost a lot to maintain. An estimated two-thirds of the indoor space isn't used, including two dorms at Johnson that stand empty during the school year.

On a recent visit to Vermont Technical College, a visitor took a wrong turn in search of the restroom and encountered a hallway full of dusty, vacant offices, their doors open. A bathroom sink had been repaired with duct tape.

Sharron Scott, the system's chief financial and operating officer, said the Randolph campus has given priority to investments in its manufacturing, engineering and computer science programs.

"Every dollar goes into operating these incredibly expensive programs, so some stuff does get shortchanged," she acknowledged.

There are savings to be found in those buildings. The system has commissioned a master planning process to determine the best way to manage what it has — including selling off property to raise some cash. VTSU sold one of its radio station licenses to Vermont Public for $80,000 and plans to sell more. And in early August, it struck a deal to sell about 35 acres of land on the Lyndon campus for about $315,000 to the Vermont National Guard.

Smith is also looking for savings through reorganizing academic programs. A student who wants to major in print journalism — available at Johnson and Castleton — will be able to do that at any campus through a combination of in-person classes and remote learning. The meteorology program that was established in Lyndon will be available to students in Castleton.

"There is a lot of redundancy in the system," said Sheahan, of the Vermont Talent Pipeline, a Burlington-area business group. "They are becoming much more efficient."

Administrators have been relying on attrition to reduce faculty and staff numbers, and it's working. Eighty-five members of the faculty and staff left the schools that make up VTSU in the past year. Sixty-five were hired in that time; faculty and staff employment is currently 618 system-wide.

Years of state underfunding and uncertainty about the future made staff dread updates about the transformation to Vermont State University, because they often contained information about newly vacated positions that wouldn't be filled, MacArthur Stine said. He resigned from his position as director of technical services at the Castleton campus on July 1 to take a job with AFT Vermont, a union that represents higher ed and health care workers.

"It's like a constant cortisol bath," Stine said of the stress. "There's too much work and not enough people."

Many professors, alumni and students say the state should pony up more money to support the system. But the annual state appropriation seems unlikely to rise much more anytime soon. Lawmakers say the system has to find a way to survive without more state support; the infusions of extra cash will be gone in a few years.

"We have seen a number of colleges actually go out of business here in Vermont because of enrollment, so at what point is the cost justifiable?" asked Sen. Kitchel, whose district includes Lyndon.

Senate President Pro Tempore Phil Baruth (D/P-Chittenden-Central) hopes to put some of the revenue from Vermont's new cannabis businesses to work helping the state colleges.

"The university has done amazing work reducing their structural deficit," he said of the system's cost-saving efforts so far. Baruth is an English professor at UVM and a former chair of the Vermont Senate Education Committee. Now he sits on the select committee that's studying VTSU. "I'm confident the system is going to strengthen as it goes forward," he said. "There should be an ongoing funding source in addition to the base appropriation."

Glimpse of the Future

A campus tour at Vermont State University-Randolph started out quietly on August 5. Three prospective students and a handful of parents listened to a presentation about the newly merged university. Then tour guide Lauryn Strahan, an architectural and building technology major from Texas, led the group around the grounds.

As the visitors passed the school's $7 million advanced manufacturing facility, they perked up. A few asked if they could stop to learn more. Conversations started to flow.

"Does everybody see this?" said Eva Deffenbaugh, a teacher from Basking Ridge, N.J., as she looked through the windows at the commercial 3D printing equipment in the advanced manufacturing lab.

The facility, paid for by a U.S. Department of Defense grant, offers sophisticated capabilities. The lab gives local businesses the chance to create prototypes — and find new graduates to employ.

"It provides opportunities for small companies to rethink how you're doing manufacturing," said Ethan LaRochelle, the owner of a 3D printing company called QUEL Imaging in White River Junction, who was touring the college with his two nephews and other family members.

Others on the tour were visiting alone, including a prospective nursing student from outside New York City and a newly hired professor of diesel mechanics named Ron Wold who had come to learn a little about his new workplace.

The technology can be used for a huge range of applications, LaRochelle said later — such as Wold's diesel mechanics.

"If he wanted to make a custom part instead of ordering it or waiting for someone to machine it, he could get the design file and load it onto the printer and make something here," LaRochelle said.

Administrators would love to drum up more of that excitement throughout the system.

Deffenbaugh and her 16-year-old son Tristan visited UVM and Champlain College before VTSU-Randolph. Tristan wants to study math and engineering. His mother said four students from her son's high school in central New Jersey are headed to UVM this year. She's not surprised.

"Burlington is a really cute campus town, cuter than many others," she said.

A sixth-grade STEM teacher whose family belongs to a ski club in Pittsford, Deffenbaugh said she was impressed with the manufacturing capabilities in Randolph and the school's ties to local businesses. Her son, she said, was excited about the idea of a long-standing program that allows students to use college manufacturing equipment to build their own skis and snowboards.

But she worried that the Randolph campus, where just 226 students lived last year, wouldn't suit him.

"He's graduating from a high school class of 500," she said. "I think this is too small an environment for him."

With so many variables at play, it's difficult to predict what lies ahead for VTSU. Seven Days put a question about the system's future to Gov. Scott in June. He said the system can't survive as it is now.

"They have an expanded infrastructure that they can't afford, and they're either going to have to lease part of that out, find out ways to profit or make money off of that, or close some campuses; it comes down to that," Scott said. "That's a decision they have to make on their own."

One bright spot for VTSU's enrollment has been the so-called early college program, which pays tuition for motivated high school seniors to earn high school and college credits at the same time. Enrollment in the program rose 25 percent this year at VTSU. Ouimet declined to release this semester's enrollment numbers for specific campuses.

Paxton Getty, 17, of Alburgh, is leaving high school early to live in a dorm at Johnson and study environmental science through the program. He plans to spend four years at Johnson, which his mother also attended, before heading on to graduate school out of state.

Paxton said he was looking forward to living in the dorm.

"This feels like walking through an area of peace," he said of Johnson's green campus, a welcoming space with well-tended buildings scaled to the size of the student population.

Paxton recently had lunch with his mom, Heather, in the Johnson dining hall at a packed event for early college students. The two said Johnson has educated their family for generations. Heather added that she had heard about the system's financial problems but was confident they'd be worked out.

Her love for the school runs deep. Because Johnson provides a lot of support to nontraditional students, Paxton's sister was able to live on campus while studying there as a single parent a few years ago.

"I don't know of a lot of other places where you'd be able to do that as a single mom," Heather said. "We're voting for Team Johnson."

CCV Is Having a Moment

The Community College of Vermont is independent of Vermont State University, but as part of the state colleges system, CCV's $31 million budget — and its fate —is closely tied to its sister university.

And the nonresidential school is one bright spot in the student enrollment picture. CCV's registrations were up 13 percent in August over the year before, according to Katie Mobley, CCV's dean of enrollment and community relations.

CCV is enjoying this boost thanks in part to a new interest in job-focused training. It's also offering an array of new programs that help Vermonters attend tuition-free — such as the 2-year-old 802 Opportunity Grant, which offers no-cost tuition to Vermonters with a family income of $75,000 or less.

With few buildings of its own, CCV also has the flexibility to start or trim courses as needed as the economy changes. Right now, the nursing and respiratory therapy programs are growing, with help from a federal grant and money from UVM. CCV offers classes in 12 locations, many of them in rented classrooms.

All CCV faculty work part time, too.

"If all of a sudden we have a rush of 100 more students saying they want to take network administration, we can quickly pivot and hire more faculty in that area," Mobley said.

Many CCV programs, such as the ones that offer prerequisites for nursing, are designed to help prepare students for nursing programs elsewhere.

"If you start at CCV, I can show you how you're going to finish a degree in four years at VTSU or UVM," Mobley said. "We map it out for you."

At $840 per class, CCV is a relative bargain. And a program that's new this fall, Vermont Tuition Advantage, halves that price for students pursuing associate's degrees or certificates in high-demand areas, such as early childhood education, accounting and cybersecurity.

"We are a single fiscal entity," Mobley said. "If VTSU is not successful, that would mean CCV would no longer be successful. We are very entwined in their future."

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

About The Author

Anne Wallace Allen

Bio:

Anne Wallace Allen covers breaking news and business stories for Seven Days. She was the editor at the Idaho Business Review and a reporter for VTDigger and the Associated Press in Montpelier.

Anne Wallace Allen covers breaking news and business stories for Seven Days. She was the editor at the Idaho Business Review and a reporter for VTDigger and the Associated Press in Montpelier.

More By This Author

Latest in Education

Speaking of...

-

'Green Mountains Review' Shuts Down Amid Vermont State University Budget Cuts

Nov 6, 2023 -

New Interim President Appointed at Vermont State University

Sep 22, 2023 -

As UVM Student Body Grows, In-State Enrollment Remains Low

Aug 21, 2023 -

National Guard to Buy Vermont State University Land for New Facility

Aug 4, 2023 -

UVM to House Grad Students in Saint Michael's Dorm

Jul 28, 2023 - More »

find, follow, fan us: