Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Business

Cannabis Company Could Lose License for Using…

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

Browse Music

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

View All

Quick Links

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

Published November 8, 2017 at 10:00 a.m.

Bob Melamede was pissed off, which seemed out of character for a laid-back guy who laughs a lot. Plus, he'd begun the day as he always does — by ingesting 80 to 100 milligrams of oil containing tetrahydrocannabinol, the psychoactive compound in cannabis. That's enough THC to leave most stoners blissed out for hours.

But Melamede saw good reason to be indignant on a late September morning outside Burlington's Bern Gallery, where the annual Pipe Classic glassblowing competition was in full swing. A retired DNA researcher, microbiology professor and international cannabis activist, Melamede had heard that a Burlington police officer confiscated all the cannabis oil from a medical marijuana patient who'd flown into town for the event.

The patient, Courtney Soper, arrived at the gallery a few minutes later. The 40-year-old mother of three from Long Island, N.Y., confirmed that, after checking into her hotel the previous night, she had driven to an Old North End café to meet some friends who were also attending the glassblowing event. While she was parking her rental car, she said, a cop pulled her over for making an illegal U-turn.

After smelling marijuana on Soper, the cop searched her car and discovered the cannabis oil. Soper handed over her medical marijuana registry cards from New York and California, explaining that she uses the substance to treat several conditions, including chronic pain. The cop didn't arrest Soper or issue a ticket, but he took her drugs.

"I said, 'I have a bottle of Adderall in my bag, also prescribed by my doctor. That's a controlled substance, too,'" Soper told Melamede. "He didn't say a thing about that."

"Who's the government to tell us what kind of medicine we can use?" Melamede barked. "Fuck them!"

He was ready to make that point at the police station, but Soper nixed the idea for fear it could bring unwanted scrutiny to the Bern Gallery event. In a text to Seven Days, Burlington Police Chief Brandon del Pozo explained later that his officer was just following protocol: Vermont doesn't recognize medical marijuana cards from other states.

Meanwhile, several twenty- and thirty-somethings milling around outside the Bern Gallery recognized Melamede and greeted him with shouts of "Hey, Dr. Bob!"

As it happens, thousands of people know "Dr. Bob," who's not a physician but has a doctoral degree in molecular genetics and biochemistry. A former research professor who taught at the University of Vermont, New York Medical College and the University of Colorado, Melamede now appears regularly in the marijuana press and frequently speaks at international cannabis conventions. His presentations, some of which can be found on YouTube, invariably delve into the science of cannabis and its relationship to human health.

Melamede is considered one of the world's leading experts on the human endocannabinoid system, the complex biological network of neurotransmitters and cell receptors that he calls "the great and powerful wizard behind the curtain." The body's endocannabinoid system produces natural compounds akin to those found in marijuana — indeed, the system was named for the cannabis plant — that regulate virtually every system in the human body. "It's like the thermostat on your wall," he explained.

As Melamede pointed out, the endocannabinoid system also includes the receptors that make pot smokers high, give them the munchies and eventually put them to sleep. Endocannabinoids explain the so-called "runner's high" of athletes and are found in human breast milk, where, he noted, they ease the trauma of childbirth and increase bonding between mother and child. As he put it, "The first thing a mother does is get the kid stoned."

Melamede is almost evangelical in espousing what he sees as the many healing benefits of marijuana. Specifically, he contends that high doses of cannabis, which contain scores of different cannabinoids, can relieve not only the symptoms of many chronic illnesses — cancer, diabetes, multiple sclerosis, HIV/AIDS and Alzheimer's disease, to name a few — but can slow and even reverse those diseases. When asked for the names and contact info of patients who've been cured by cannabis, he said, "How many hundreds do you want?"

Melamede's assertions about the plant's curative properties put him well outside mainstream thinking in academia, medicine and pharmacology. Almost no medical professionals or academics contacted for this story would comment on the record about him. Some said they respected his intelligence and academic credentials but disagreed with his interpretations of the science. For example, Melamede insists that cannabis can cure cancer. There's insufficient peer-reviewed research to back that claim. Yet, as Melamede and other cannabis activists point out, such studies have been virtually impossible to perform in the United States. The federal government lists marijuana as a Schedule I drug with no accepted medical use.

One Burlington physician, who did not want to be named, noted that Melamede is "a local hero in the eyes of some."

Others, however, find his blunt, in-your-face style off-putting.

"He has the potential to alienate people because of the way he communicates sometimes," said Laura Lipton of Charlotte, the second of Melamede's three ex-wives. The father of four has five grandchildren. "A diplomatic Bob Melamede would be an oxymoron."

Agree with him or not, "Dr. Bob is about as famous as you can get in the underground cannabis world," said Dylan Raap, CEO of Green State Gardener, a Burlington-based store that caters to indoor growers, particularly medical marijuana patients. "He's universally respected and one of the top names in the industry."

Traditional types, too, acknowledge his advocacy. As doctors, legislators and law enforcement officers in Vermont and elsewhere are coming around on cannabis, Melamede looks increasingly prophetic.

Renegade Healer

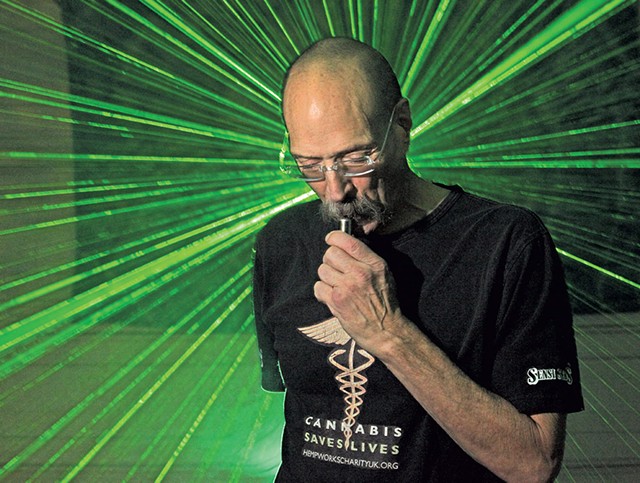

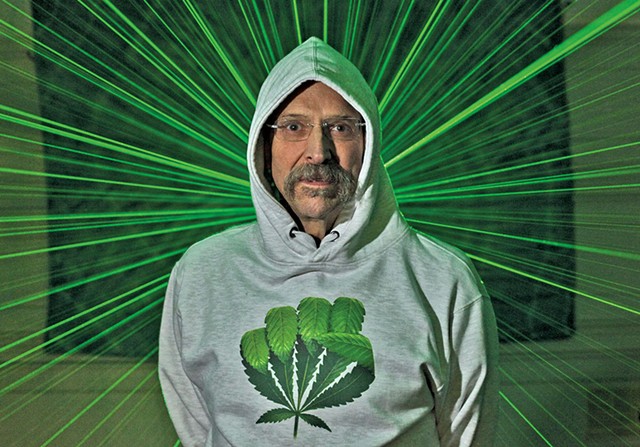

Melamede resembles an R. Crumb character come to life. Lean, fit and balding, with wire-rim glasses and a bushy, '70s-style mustache that frames his seemingly perpetual grin, he looks a decade younger than his 70 years. He credits his good health and youthful appearance to high daily doses — about 200 milligrams — of high-potency THC oil, his "anti-aging drug."

"I'll show you shit that will blow your fucking mind, OK?," he said from the couch in the Burlington South End condo he's occupied for two years. The self-described "stoned-out hippie" wore shorts and a T-shirt emblazoned with a marijuana leaf and the words "Phoenix Tears" — an international nonprofit foundation that promotes cannabis education, research and advocacy. Melamede long served as the group's science adviser and program director. He's also been involved with several cannabis-related businesses, including as former president and CEO of Cannabis Science, a publicly traded biotech firm based in Irvine, Calif.

Though our interview was scheduled to last about an hour, Melamede talked for more than three, at times following scientific threads all the way back to the big bang, the rise of vertebrates and the emergence of CB1, the first mammalian cannabinoid receptor.

He saved his most stinging criticism — and colorful language — for the medical establishment and Big Pharma. "Our government doesn't want us well. They want us sick. We're dollar signs," Melamede ranted.

The conversation was regularly interrupted by phone calls from overseas friends and business associates, some of whom, he admitted, were felons with pot-related convictions.

Although ostensibly retired, "I'm busier than I've ever been in my life, I work harder than I ever have in my life, and I spend more money than I've ever had in my life," Melamede said. He isn't just a popular former college professor who lectures worldwide on medicinal cannabis; he's part of a loose global network of underground activists, which he likened to the computer hacker group Anonymous.

"Right now, there are people all around the world treating people with all sorts of illnesses, a whole counterculture medical establishment," he explained. "The difference is: Ours works, and it's free, or as close to free as we can make it."

Earlier that day, he learned that his girlfriend, Danica Una Petrovic, had been arrested in Belgrade, Serbia, for possession of cannabis oil. According to Melamede, she'd allegedly used cash contributions from anonymous donors to provide cannabis oil to patients suffering from cancer, multiple sclerosis, seizure disorders and the like. Most, he noted, live in places where medical cannabis is illegal.

"When they arrested her, they said, 'We know you're not a criminal,'" Melamede reported. "She said, 'Then why are you stealing medicine from sick people?'" At press time, Petrovic was no longer in police custody.

Melamede has never been convicted of a crime himself, but a Vermont financial institution recently terminated his accounts for reasons it wouldn't disclose — even to him. Western Union has also banned him from wiring funds internationally, presumably because it suspected he was financing illegal activity.

But his pariah status among bankers and mainstream scientists hasn't deterred Melamede's followers. During our interview, an unexpected guest, Valorie McMahon, showed up at his door. Originally from Los Angeles, the 49-year-old Woodstock woman credited Melamede with turning her health around after conventional medicine failed her "miserably."

In October 2004, McMahon was diagnosed with a fibrous tumor on her uterus, which, her doctor told her, could be removed via laparoscopic surgery in about 45 minutes.

"Eight hours later," she said, "I came out of surgery, and they'd stripped me of all my female parts."

According to McMahon, doctors wrapped mesh around her bladder and vaginal wall. When the mesh eroded, part of it migrated elsewhere in her body, which later resulted in the removal of part of her intestines. In all, McMahon required seven surgeries to fix the problem.* As her condition deteriorated, so did her finances. Due to her exorbitant medical bills, McMahon eventually lost her home and business. Her son had to drop out of college. As recently as three years ago, she had 26 tumors throughout her body.Today, she said, she has only one benign tumor, which she's managing.

"How did I do that? Cannabis oil," she asserted. "Chemotherapy almost killed me. Radiation and surgery almost killed me. All the drugs they put me on made me crazy. Dr. Bob recommended a plant."

His motivation is altruistic, according to friends and colleagues. All five patients interviewed for this story said Melamede never asked them for payment of any kind. Lipton, who was married to him from 1972 to 1984, said her former husband travels on his own dime to conventions and has testified as an expert witness at the trials of people jailed for illegally using cannabis medicinally.

"One thing important about Bobby is, he marries heart and mind, his science with his compassion," Lipton said. "If there's something that can be bettered because people are suffering or ill, his science is telling him that something can be done about it. So he will put himself on the line for what he thinks is right every time."

Weird Science

Melamede didn't discover science the way most boys did in the wake of World War II. He was born and raised in Manhattan near the George Washington Bridge, the son of a veteran and his German war bride. Bright and bored, he went off to Herbert H. Lehman College in the Bronx at 16 — one year after researchers James Watson and Francis Crick won the Nobel Prize for cracking the genetic code and discovering the double-helix structure of DNA.

That revelation became the backdrop for his belief system. "My whole life I was always interested in: What is life?," he explained. "And that's why I went into biology."

It took a while to find his path. At least initially, Melamede didn't take his studies seriously and nearly flunked out. One day, while he was messing around with some chemicals in his bedroom, a mortar and pestle exploded in Melamede's hands, blowing off his fingertips and severely burning his face and body. He briefly dropped out of college, he said, which gave him time to regroup.

And get high. Around this time, Melamede discovered marijuana. As he put it, "The more pot I smoked, the more I realized that, if you go to college, you should be there to learn and not be an idiot."

Melamede soon buckled down with his studies, eventually graduating first in his class. He went on to pursue a master's degree at Lehman, then a doctorate in molecular genetics and biochemistry at City University of New York. While working on his PhD, Melamede met his then-adviser, Susan Wallace, who now chairs the UVM Department of Microbiology and Molecular Genetics. Wallace didn't reply to several requests for an interview about her former student and colleague.

Melamede followed Wallace to Lehman, New York Medical College and eventually UVM in the late 1980s. As a research professor, Melamede ran the lab and became an expert in DNA repair and free-radical damage, which he calls "the friction of life." Cannabinoids, he suggested, reduce that friction.

In the late 1970s, Melamede discovered the work of Ilya Prigogine, a Belgian chemist who won the Nobel Prize in chemistry in 1977 and pioneered a new field known as nonequilibrium thermodynamics. Based on Prigogene's writings, Melamede began formulating his own theories on the fundamental physics of life. They eventually helped him understand the unique role that cannabinoids play as anti-aging compounds.

"All biochemical change, good or bad, is stress. And the way we handle stress is with our cannabinoid receptor system, because it's what allowed our brain to develop," Melamede explained. "It's the No. 1 neurotransmitter system in our brain. No. 1! And we haven't been teaching it to fucking doctors!"

Matthew Hogg is chief editor at Green Mountain Editing Services in Burlington. He got his doctorate at UVM and worked for years in the same molecular biology and genetics lab as Melamede.

Hogg said that, by the time they met in 1997, Melamede was already "a bit of a celebrity" among Burlington's stoner set, organizing pro-marijuana rallies and annual 4/20 toke-ins on campus.

Throughout the '90s, Melamede dabbled in politics and the Vermont Grassroots Party. In 1994, he challenged Jim Jeffords for his U.S. Senate seat; in 1996, he ran against then-U.S. representative Bernie Sanders; and, in 1998, he took on Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.). Though Melamede never garnered more than about 2,500 votes per race, Hogg remembered him as being "very popular" among college students.

"I'd walk around town with him putting up posters and go to lunch, and everybody would yell, 'Dr. Bob! Dr. Bob!' Kids would run up and high-five him," Hogg said. "It seemed like everybody knew him."

Whenever Melamede gave lectures on campus on his favorite topic, Hogg added, "the room was standing room only."

If college students were high on Melamede, his fellow faculty members were far less so. This was particularly true, Hogg recalled, among medical faculty who seemed deeply skeptical, even scornful, of Melamede's views on endocannabinoids.

"I don't think any of them wanted to believe or agree with him, because he's a crazy hippie walking around in his tie-dyes, long hair and ponytail being goofy," Hogg said. "I think he found that to be very frustrating — and enlightening in many ways — that these people who are supposedly the paragons of medical knowledge were, and still are, amazingly ignorant about many things in the human body.

"But I knew immediately when I met Dr. Bob that he's a genius," Hogg continued. "You can't argue against what he's saying, because the science is all on his side."

In September 2001, Melamede left UVM and, at the invitation of Karen Newell Rogers, a former UVM colleague, accepted a faculty position chairing the biology department at University of Colorado-Colorado Springs. Efforts to reach Newell Rogers for comment about her former colleague were unsuccessful. A current administrator in that university's biology department confirmed Melamede's tenure but didn't reply to interview requests.

For more than a decade starting in 2002, Melamede taught a class called Endocannabinoids and Medical Marijuana, which he claims was the first-ever college-level course on the human cannabinoid system.

"And then I became an outcast in the scientific community because I talked about cannabis curing cancer," he said. "They didn't want to hear that."

As he spoke, Melamede pulled up dozens of before-and-after photos on his laptop of tumors that, he claimed, were healed by cannabis treatments. In fact, he boasted about curing cancers at a rate of about 80 percent. They included at least four people around the world who beat pancreatic cancer — a disease with a patient survival rate of 2 percent after five years — through high-dose cannabis treatments. It's a claim Melamede readily admitted most experts would find dubious.

"That's why I'm freaked out, OK? You can't believe it? Trust me, I can't believe it!," he said, then cackled loudly.

The U.S. Food & Drug Administration doesn't believe it, either. Last week, it sent letters to four U.S. firms warning them to stop selling cannabis-based products that claim to "prevent, diagnose, treat or cure cancer" without sufficient scientific evidence. As FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb said in a press statement, "We don't let companies market products that deliberately prey on sick people with baseless claims."

In an email to Seven Days, Vermont Commissioner of Health Dr. Mark Levine echoed the FDA's concerns and urged "great caution" about therapies and products that claim to diagnose, treat or cure cancer without science-based evidence to support them. But he also called on the federal government to reclassify cannabis — a prerequisite for real research.

Melamede said he has all of the evidence he needs and will defend his science against anyone who challenges it. As he put it, "I'm a very, very conservative scientist, and I can back up everything I say."

Alzheimer's Antidote?

One of the most intriguing Dr. Bob stories came from a relative of his, whose husband was diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease two years ago. "Judy" lives in a southern state where medical cannabis is not legal. She asked that her real name be withheld, for fear of compromising her husband's ongoing treatments — and her own legal status.

"Alzheimer's was always somebody else's disease and somebody else's problem," she said, "until it became ours."

Judy's husband, "Don," was a surgeon for 50 years. A native of Romania, he spoke four languages. In 2015, after noticing difficulties with his memory, Don went to a neurologist who confirmed the Alzheimer's diagnosis. As a lifelong physician, Don followed a standard protocol and began taking Aricept, an FDA-approved pharmaceutical drug for the neurodegenerative disease.

In February, Don fainted and was taken to the hospital. His doctor took him off Aricept and put him on Namenda, another Alzheimer's medication. Still, Judy watched Don's condition worsen. His blood pressure dropped dangerously, and eventually he reverted to speaking only Romanian. After suffering a seizure, Don was taken off Namenda, too.

By April, Judy said, Don began having hallucinations and delirium and was running away from home on a regular basis. He also slept no more than an hour at a time. When he was awake, she said, he'd rummage around the house, emptying closets and drawers.

On April 18, Judy had no choice but to admit Don into a memory-care facility, where a physician diagnosed him with Stage 6 Alzheimer's, or "severe decline" — Stage 7 is the most advanced. Judy said that the medications Don took to calm him down and help him sleep triggered rapid weight loss and more seizures. Eventually, Don refused to take any pills, including his diabetes medications.

In early July, at Melamede's suggestion, Judy started her husband on cannabis-laced cookies. Judy, who's kept a journal of Don's condition since he was diagnosed, said she began to notice significant improvements. He started sleeping more, from one hour a day to five. The facility staff reported that he seemed far less agitated and even began recognizing them by name. And, Judy noted, his language skills started to return.

Three months after Don began taking cannabis, Judy said, "he has good days, bad days and what I call 'wow!' days, when he's like a completely different person, so much like normal that it's like, oh my gosh! I can't believe this!"

Melamede wasn't surprised by Don's progress, saying a lot of "well-documented science" supports his improvements. Cannabis, he explained, is neuroprotective, meaning it stops further deterioration of neurons. How much daily cannabis did Melamede recommend to achieve those results?

"Maybe a joint's worth," he said. "It doesn't take a lot."

What looks like a miracle cure to a family member, however, could amount to malpractice if Melamede were a medical doctor. Dr. Joseph McSherry, a long-time neurologist at the UVM College of Medicine, said he finds some of Melamede's ideas "curious" and agrees with some of his views on the healing potential of cannabis. In the early 2000s, he testified before the Vermont legislature in favor of legalizing medical marijuana.

However, he was unwilling to parse the veracity of Melamede's claims.

"Cannabis has many remarkable medical benefits and may work adjunctively with pharma medications, better than opioids for chronic conditions," McSherry wrote in an email. "But I have known believers who had cancer and died, so patients (buyers) beware ... I know of no one in the Vermont medical community who recommends [Melamede] or follows him, including me."

Karen Lounsbury and Wolfgang Dostmann, both UVM professors of pharmacology, had a similar reaction during a June 2016 Community Medical School event on the subject of medical cannabis. A videotape shows that the two presenters were respectful of Melamede, who was in the audience, but were unwilling to embrace his assertions without clinical research to support them.

"I've actually looked at all of your videos, because I find them very interesting, with a lot of good content," Lounsbury told Melamede. "But we are a college of medicine where we rely on evidence-based medicine."

Dostmann agreed, saying that there are "probably thousands" of patients around the world who've benefited from cannabis. The problem, he noted, is that clinical and basic research is prohibited by law, "so no one in this room can engage in clinical trials ... As of just a few months ago, we weren't allowed to get cannabis in our laboratories."

When Melamede countered that he and his colleagues have cured "thousands" of cancer patients around the world, Dostmann cut him off.

"I'm sorry," Dostmann interjected, "but these are just anecdotes."

One heavy hitter gives Melamede a little more credit. Roscoe Moore served as a U.S. assistant surgeon general from 1995 until 2003 under then-U.S. surgeon general Joycelyn Elders. Moore is also a former chief epidemiologist with the Center for Devices and Radiological Health at the FDA and a former assistant professor of oncology at Howard University Cancer Center. Moore briefly worked with Melamede in a cannabis-related business but no longer has any professional or financial relationship with him.

"I would say the science makes sense," Moore said of Melamede's work in a recent phone interview. "The question is the applicability."

He also conceded, "I think that Dr. Bob is on the right trail."

Does Moore see potential dangers in Melamede overstating his case?

"Dr. Bob is an advocate. I would compare it to the advocacy for people with HIV/AIDS," he clarified. "If advocates didn't push the issue of HIV/AIDS, we may not be where we are today."

*Correction, November 8, 2017: An earlier version of this story mischaracterized the nature of Valorie McMahon’s medical complications that led to her use of cannabis as therapy.The original print version of this article was headlined "Cannabis Calling"

Related Locations

-

Bern Gallery Smoke Shop & Cannabis

- 135 Main St., Burlington Burlington VT 05401

- 44.47565;-73.21352

-

802-865-0994

802-865-0994

- berngallery.com…

-

Green State Gardener

- 699 Pine St. Suite C, Burlington Burlington VT 05401

- 44.46023;-73.21494

-

802-540-1168

802-540-1168

- greenstatedispensary.com…

Related Stories

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

Tags: Health Care, Cannabeat, cannabis culture, recreational cannabis, cannabis policy, cannabis products, medical cannabis, The Bern Gallery, Green State Gardener, Video, Recommended Reading

More By This Author

About The Author

Ken Picard

Bio:

Ken Picard has been a Seven Days staff writer since 2002. He has won numerous awards for his work, including the Vermont Press Association's 2005 Mavis Doyle award, a general excellence prize for reporters.

Ken Picard has been a Seven Days staff writer since 2002. He has won numerous awards for his work, including the Vermont Press Association's 2005 Mavis Doyle award, a general excellence prize for reporters.

About the Artist

Matthew Thorsen

Bio:

Matthew Thorsen was a photographer for Seven Days 1995-2018. Read all about his life and work here.

Matthew Thorsen was a photographer for Seven Days 1995-2018. Read all about his life and work here.

Speaking of...

-

Cannabis Company Could Lose License for Using Banned Pesticide

May 7, 2024 -

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize' Vermont’s Weed Culture

Apr 17, 2024 -

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host State's First Weed 'Farmers Market'

Mar 20, 2024 -

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

Mar 8, 2024 -

Burlington: What to See, Do and Eat During the Eclipse

Jan 25, 2024 - More »

Comments (19)

Showing 1-10 of 19

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.

- 1. A Farting Bear Caught on Camera Is What We All Needed to See True 802

- 2. Immigration Officials Illegally Deported Vermont Family, Advocates Say News

- 3. Rita Mannebach Traveled From Florida to Vermont to Choose How She Died Health Care

- 4. An Inmate’s Pleas About Her Dangerous Cellmate Were Dismissed. Then She Was Attacked. Crime

- 5. Some Residents Flooded Out of Plainfield Think Goddard’s Campus Should Become Home Economy

- 6. Vermont's Local News Publishers Are Endangered. Can They Be Saved? Media

- 7. Vermont Farmers Experience a Second Devastating Summer of Flooding Environment

- 1. A Farting Bear Caught on Camera Is What We All Needed to See True 802

- 2. Rita Mannebach Traveled From Florida to Vermont to Choose How She Died Health Care

- 3. Moving on From Its Industrial Past, St. Johnsbury Is Attracting Young Entrepreneurs and Building a Vibrant Downtown Economy

- 4. Heavy Rains Hit Vermont Again as Flooding Washes Out Roads News

- 5. Neighbors Band Together to Save Cattle From Hinesburg Floodwater Environment

- 6. Vermont Health Officials Prepare for Bird Flu as It Spreads in Dairy Herds News

- 7. Vermont's 'Orwellian' Butter Gets a Shout-Out in Hit Show 'The Bear' True 802