click to enlarge

Angela Pandis starts most of her personal finance classes with a question. On March 14, the Missisquoi Valley Union High School teacher asked students to ponder what people fear most about using credit cards.

"Having to pay it back," one student ventured.

"Not being able to pay it off," another said.

The top answer from a recent survey, it turned out, was identity theft, Pandis told the class. That prompted one student to share that her dad had recently become a victim of credit card fraud.

"That's awesome — well, maybe not awesome, but that's a great example," Pandis said, to laughter.

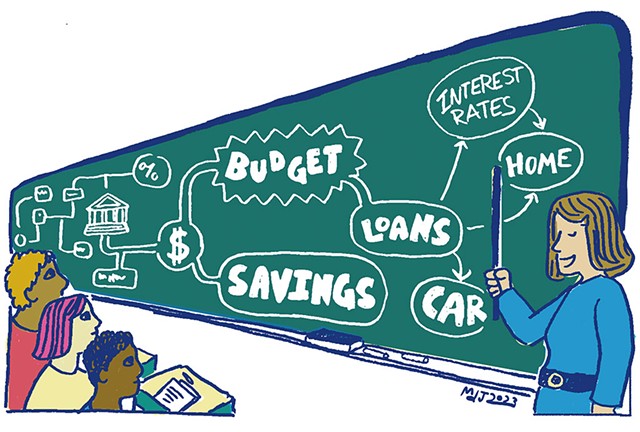

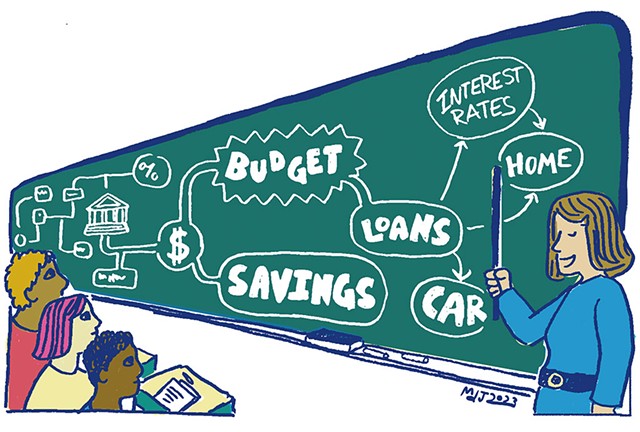

So began the "Intro to Credit" lesson in the semester-long course, which all MVU students must take before they graduate. Over the next hour, Pandis covered different types of loans and interest rates, and explained what happens when borrowers miss payments. Students followed along on their laptops, taking quizzes and watching animated explanatory videos.

Just five states required high schoolers to take personal finance in 2018, when Pandis first started teaching the subject. But that number has more than tripled since, and 28 states, including Vermont, are considering legislation to mandate the coursework.

Vermont's bill, H.228, likely won't see action this year. But the real-world relevance of the curriculum it champions has convinced educators that it's time for the state to catch up.

Leading the legislative push is the advocacy arm of Next Gen Personal Finance, a California-based nonprofit that provides teachers with free lesson plans. The organization created the NGPF Mission 2030 Fund in 2021 to lobby state legislatures to mandate personal finance courses for every high schooler. The campaign has paid off: Nine states have passed such bills, including five lobbied by Mission 2030.

Vermonters overwhelmingly support financial literacy education. More than 80 percent of respondents to a recent survey from Champlain College's Center for Financial Literacy said high schoolers should have to take a basic finance course. But of Vermont's 55 public high schools, just 11 have adopted the mandate, according to research by Winooski High School teacher Courtney Poquette. Winooski, for example, began requiring the course in 2021; MVU has done so since 2012.

By Poquette's count, another 28 schools offer a personal finance class but don't require it, and about 16 others touch on personal finance in another course.

But without a statewide law, schools don't consistently offer the class. In 2018, 14 Vermont high schools required personal finance; five years later, that number has dropped by three. Poquette, who has taught personal finance at Winooski for 17 years, said some schools don't replace business teachers if they leave; others nix the class to reduce school spending.

"It's ironic that we would fix a budgeting issue by cutting the class that teaches about budgeting," Poquette said.

Rep. Michael Marcotte (R-Newport), who cosponsored Vermont's bill, said taking a business course in high school gave him the know-how to open a convenience store in 1983; he still runs it today. Marcotte recalled learning how to balance a checkbook by hand but said today's teens need more advanced lessons, such as learning how a debit card works and how to manage debt, particularly if they're college-bound.

"If we can provide that information and that teaching to our students, I think in the long run they'll be better off," Marcotte said. "They can make better, informed decisions."

Proponents of financial literacy education also argue that the classes can help close racial wealth disparities. Black, Indigenous and people of color have historically been excluded from homeownership — the primary way of building generational wealth — thanks to now-illegal racist lending policies. Black Vermonters also earn less than their white counterparts: just $0.67 to the dollar, according to the federal Department of Labor.

Winooski resident Dylan Rhymaun, who works for a financial record-keeping firm and is Indian American, said personal finance courses could have an outsize impact on people of color — particularly in immigrant families where the parents may not be well versed in money matters. Students could share their newfound knowledge at home, Rhymaun said.

"Education for one member of the family, in this subject, is beneficial for the whole family," he said.

H.228 missed the "crossover" deadline to advance to the Senate, meaning it's stuck in the House Committee on Education for another year unless the language is tucked into another bill. Committee chair Rep. Peter Conlon (D-Cornwall) said he sees the proposal's merits but wonders how it would be received in cash-strapped districts that proudly proclaim their independence. School boards generally dictate class offerings, not the legislature, Conlon said.

"It would definitely set a precedent that this is something that the legislature can do and does, and that may not be the best thing in the world," Conlon said. "[We may need to] find a better balance between local control and making sure our kids have equity across the state."

Yanely Espinal, director of educational outreach for Mission 2030, argues that mandating personal finance is simply good governance. She pointed to data showing that students who took such a class tend to have less college debt. Local officials would still decide how to teach the subject, Espinal added, from choosing the curriculum to determining how many credits a course is worth.

Poquette, the Winooski teacher, said her students have had no trouble meeting graduation requirements even if they're also taking Advanced Placement classes and other electives. She thinks there's a lot of support to make the course mandatory statewide.

"I've never had anybody ... say, 'That class isn't important to graduate,'" Poquette said. "Most of the time, people say, 'Thank you for teaching it. This is so important. I wish I learned this in school.'"

Back in Pandis' classroom, MVU students were learning about loans. Pandis queued up a video featuring a surfer character who used beach metaphors to explain the mechanics of borrowing.

"Interest rates are like ocean tides," he said in a cliché SoCal accent. "They vary by a ton of different factors — and nobody knows how they actually work!"

The video was goofy but effective. After the lesson, students understood the difference between fixed and variable interest rates. They also learned how to calculate a person's net worth, cementing the concepts of assets and liabilities.

Ricky Velez, 18, a senior from Swanton, said he was initially intimidated by the course because the topic was so foreign to him. Three months in, he can see why it's required.

"The class really taught me the importance of things like savings and the right way to use credit cards rather than trying to figure it out myself," he said. "You're gonna go into the class thinking it's boring ... until you use the information."

His classmate Ava Hubbard agrees. The 17-year-old from Swanton said she never paid much attention to her cash flow before taking Pandis' course. Now she uses a banking app that sends alerts whenever she spends or deposits money. It's particularly satisfying when her paycheck hits her account, she said.

Hubbard, a senior, said she hopes to study business at Saint Michael's College after she graduates. Could this class give her a leg up in her coursework? It's possible.

"A lot of people just don't know a lot about these skills," she said.

Clarification, March 30, 2023: This story has been updated to more accurately describe the fund that lobbies for personal finance classes.