Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

-

Education

Scott Official Pushes Back on Former State…

-

News

Burlington Budget Deficit Balloons to $13.1 Million

-

Education

Senate Committee Votes 3-2 to Recommend Saunders…

- Court Rejects Roxbury's Request to Block School Budget Vote Education 0

- Norwich University Names New President Education 0

- Media Note: Mitch Wertlieb Named Host of 'Vermont This Week' Health Care 0

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

The Pentagon Is Stocking Vermont With Tools of War

Published November 26, 2014 at 10:00 a.m.

Orange County has fewer than 30,000 residents, more miles of snowmobile trails than paved roads and only one stoplight. In Chelsea, the county seat, a courthouse bell chimes every time a jury reaches a verdict. Cellphone reception is notoriously unreliable.

It is among the most tranquil places in a state that ranks 50th nationally in per capita violent crime. And yet, the local sheriff has told the U.S. Department of Defense that Orange County is a key front in the war on drugs.

"There is a high demand for drugs among local residents. We have seen primarily usage of marijuana, opiates and various prescription pill forms," Orange County Sheriff Bill Bohnyak wrote in an application for military gear this year. "This has led to a gross increase in the amount of burglary and theft calls. Many of them involved firearms, whether used in the crime or stolen."

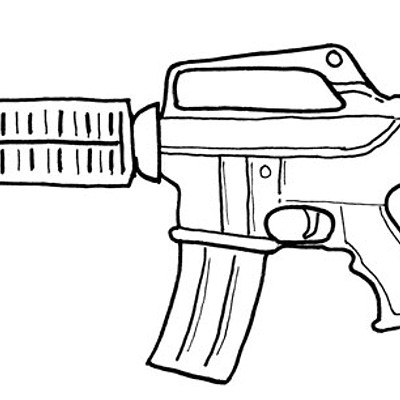

In response to its request, Bohnyak's department received two Humvees, four assault rifles, scopes, night-vision goggles and other crime-fighting gear. And the Orange County bounty is not anomalous.

In the past 17 years, law-enforcement agencies across Vermont — from the state police to village departments to the fish and game department — have quietly amassed an arsenal from the Pentagon's surplus equipment program.

Together, Vermont agencies have acquired 158 assault rifles, 14 military Humvees, and scores of scopes, sights and other equipment. They have requested, but been denied, more than twice as much stuff.

The national distribution of military equipment left over from America's foreign wars and domestic stockpiles, known as the 1033 Program, received little scrutiny until last summer, when a young black man was gunned down by a police officer in Ferguson, Mo., and the ensuing protest turned violent. Officers showed up in body armor and brandished sniper rifles, armored vehicles and other gear more commonly seen in overseas conflicts than on U.S. streets.

Angry confrontations with police were repeated there this week after a grand jury did not indict the shooter, leading to fires, tear gas and unrest.

To better understand why Vermont departments are seeking free firepower and heavy equipment, Seven Days obtained nearly 4,000 pages of records from the Vermont National Guard, the agency tasked with implementing the 1033 Program over the past 17 years.

The Montpelier Police Department cited the overdose death of an "IV heroin user" in a request for four M14 assault rifles. Swanton police, who obtained two Humvees for their four-man department, referenced "international smuggling operations." Hardwick police asked for utility trucks and assault rifles to help with their "marijuana eradication" efforts.

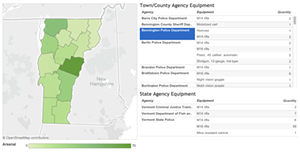

Top 10 Vermont recipients of 1033 Program items

Orange County Sheriff: 66 Vermont State Police: 66 Swanton Village Police: 36 Hartford Police: 26 Rutland Police: 10 Berlin Police: 10 Manchester Police: 7 Vermont Dept of Fish & Wildlife: 7 Chittenden County Sheriff: 7 Brattleboro Police: 7

Want to know what your police department got from the Pentagon? We've got you covered. Check out our online database at sevendaysvt.com/militarygear

The buildup has occurred not just in the state's larger communities but in upscale, touristy towns. Middlebury police referred to their ongoing struggles with "drug trafficking" and their location on a "major pipeline for narcotics carriers" — Route 7, presumably — in requesting assault rifles and bullet-resistant helmets. Shelburne police, noting "4,000 summer tourists," got two M14s, though they asked for more. Police in Norwich, where the median home price is more than $500,000, referenced a "transient drug problem," and "marijuana cultivation" to help justify a free M16.

Vermonters have had very little say in the matter — although some police chiefs consulted their selectboards before applying. And the buildup has come while the state has seen a dip in most categories of crime. Since 2005, both violent and property crimes have declined in Vermont, according to federal statistics.

"Besides the stigma of being military equipment and looking like military equipment, you have to take everything on a case-by-case basis — each piece of equipment, what it is and the agency using it," said Lamoille County Sheriff Roger Marcoux Jr., whose department has acquired two Humvees and three M14 assault rifles. "I like to think that law enforcement in Vermont are pretty responsible."

But this trend toward militarization has alarmed plenty of citizens, from civil libertarians to war veterans.

"It's an arms race," said Allen Gilbert, director of the Vermont chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union. "When you have more powerful and precise tools, there's a chance they will be used in ways that are not consistent with traditional methods that law enforcement has used for years.

"When you start equipping the police with military weapons, they begin to act more like the army than like beat cops," Gilbert said.

Protection or Provocation?

Last August, local and state police responded to a call about a man threatening suicide at home in Duxbury. When they arrived at his home, at about 5 p.m., police say the man fired a gun in their direction. Backup soon arrived, en masse.

With more than 20 vehicles, police blocked off the otherwise quiet cul-de-sac. A helicopter circled overhead. Troopers wearing vests and helmets and holding shotguns hid behind an armored truck — acquired years earlier, outside the 1033 Program — that crawled up the driveway toward the man's house, where they eventually found him dead of a self-inflicted gunshot wound.

Police say they need to protect themselves in such volatile situations. But some critics wonder if using military-style force against the unstable man acted to inflame, rather than stabilize, the situation.

"You have to wonder, if you're not balanced and undergoing tremendous mental distress, what does the appearance of armored personnel carriers plus police in camouflage with high-powered rifles do for you?" Gilbert said. "I am going to guess it certainly doesn't reassure you."

Another question: Is the program funneling weapons into an overly aggressive law-enforcement system? While there has not been a Ferguson-like protest in Vermont, there have been plenty of incidents during which well-armed police have confronted citizens in ways that some have considered excessive.

In 2006, the Vermont State Police Tactical Services Unit — Vermont's leading SWAT unit tasked with responding to standoffs and active shooters — responded to a schizophrenic man living in the woods in Corinth. Members dressed in camouflage and holding assault rifles approached Joseph Fortunati, who, hours earlier, had brandished a handgun at passersby. He tried to run away and refused to surrender. TSU agents eventually surrounded him and, after he tried to pull a handgun from his waistband, they shot him to death, police said.

Fortunati's family members repeatedly chastised police for responding with military-scale force, which they said exacerbated the situation.

Just across the Connecticut River, Keene, N.H., received national attention last month when drunken college students on a mini-rampage prompted police to deploy their dogs and brandish assault rifles, tear gas, Tasers and pepper spray.

"It's a touchy topic, we understand that," said Vermont State Police Capt. Tim Clouatre. "But we don't see those incidents in Vermont."

As proof of their restraint, a few Vermont officials cited a recent protest against the Vermont Gas pipeline expansion. Protesters entered the Pavilion Building, which houses the governor's office, and refused to leave. Numerous state police troopers and local officers showed up, and, after officials bought the protesters pizza at the governor's request, officers peacefully arrested them.

"This is a good program," Clouatre says of 1033. "It would be nice to tell you that we'd never have to use this equipment, but bad people have done bad things, and our job is to keep people safe."

The Man With the Goods

In recent years, Randall Gates has been the go-to man for Vermont police chiefs in the market for military gear. A soft-spoken lieutenant colonel in the Vermont National Guard, Gates prides himself on the "customer service" he brings to his job as the Vermont manager of the 1033 Program.

Since its inception in 1997, the program has given away more than $4.3 billion in equipment to 8,000 police agencies across the country, according to the federal government. In 2013 alone, it gave away nearly a half billion dollars' worth of gear.

Up for grabs: airplanes and helicopters, boat trailers, heavy vehicles, rifle sights, desk equipment, and more. The items are free, though police are on the hook for shipping and transportation costs.

Gates said he attended conferences of police and sheriffs' associations to tout the available equipment and help build interest in the program.

"It's deriving additional value for the taxpayer," Gates said. "If you can extend the equipment's life by giving it to law enforcement for five to 10 years, you're extracting extra value."

On a secure website, police can view a catalog of available equipment and submit an application. If police prefer, they can visit military bases in person and select unclaimed items from their warehouses, Gates said.

"You can walk up and down the aisle and say, 'That will work, that will work,' and if nobody has spoken up for that piece, you are free to take it," Gates said. So far, no Vermont agency has asked for either an airplane or a helicopter.

Most of the Vermont gear comes from bases in upstate New York, New Hampshire or Connecticut, Gates said. Some equipment is nearly new, while other pieces date back to the Vietnam War.

The police chiefs send a letter to Gates' office, which vets it, checks it for accuracy and forwards it to the U.S. Department of Defense Law Enforcement Support Office in Michigan, where final decisions are made. While more populous states have entire staffs dedicated to the 1033 Program, Gates said the Vermont Guard folds the program in with other responsibilities and handles a couple of inquiries per day.

The Vermont State Police have received more equipment than any other local law- enforcement agency, including 59 M16s — which is far short of the 250 they requested in 1997 — and six M14s. American soldiers in combat zones use both these semiautomatic rifles.

The rifles aren't for the state police's TSU, which has purchased more modern weaponry within the regular operating budget. Patrol troopers don't carry them much anymore, either. In the past, such weapons were stored in the trunks of their vehicles, according to Clouatre. In recent years, the troopers, too, have updated. Most of Vermont's M14s are now in storage, only to be used in an emergency.

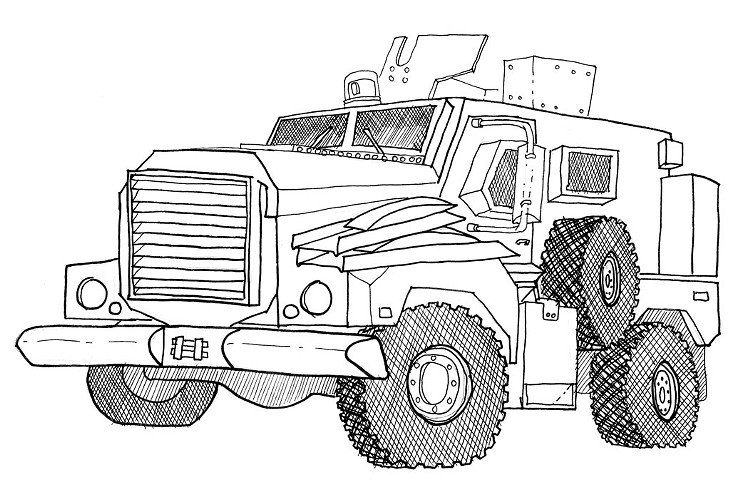

Earlier this year, state police obtained a Mine-Resistant Ambush Protected vehicle, or MRAP — a 14-ton truck designed to protect soldiers from improvised explosive devices embedded in war zones. In fact, the Marines say the MRAP was the single most effective defense against IEDs in Iraq.

"Blast-resistant underbodies and layers of thick, armored glass offer unparalleled protection, while all-terrain suspension and run-flat combat tires ensure Marines can operate in complex and highly restricted rural mountainous and urban terrains," reads the description on the U.S. Marines website.

Each MRAP costs the Pentagon about $500,000; Vermont State Police got one for free, but had to spend $80,000 to remove its machine-gun turret, repaint it and convert it to civilian use.

On a Roll

Vermont's sole MRAP has yet to see any action. It's stored in Williston, and state police are developing precise guidelines for how it could be used. Clouatre said it could provide cover for police encountering armed people who have threatened violence. It's likely that only the commissioner of public safety or the commander of the state police will be authorized to let it to roll, he said.

Members of a group of Vermont military veterans, Veterans for Peace, hope to persuade lawmakers to stop that from happening. They cite the MRAP as Exhibit A in their case against militarization.

"This amounts to a completely different image for our state police, super-militaristic and more like an occupying force," Charlotte resident Lawrence Hamilton wrote to lawmakers. "Once this new militaristic image is well established, we will undoubtedly see an increasing presence of armored and other U.S. Army surplus vehicles cruising our neighborhoods, letting us know who is boss."

No other agency in Vermont has obtained an MRAP — Bohnyak, in Orange County, was turned down earlier this year — and Gates said it is unlikely any agency but the state police would ever be able to justify getting one.

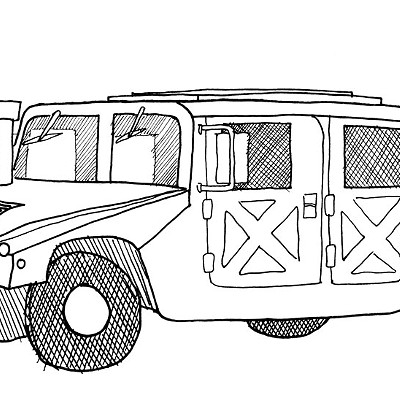

But local departments have availed themselves of other vehicles. Vermont has received at least 14 military Humvees.

In addition to Orange County's two, the Lamoille sheriff's department has a couple, as do the Swanton and Richmond police. Manchester police got four. The Bennington Police Department and the Windham County Sheriff's Office each have one.

Richmond Police Chief Alan Buck said his Humvees are not for patrols. Rather, he views them as emergency equipment that can help first responders reach remote areas during foul weather. He has one for the road and another to strip for parts. In fact, the Humvee helped rescuers reach an injured woman thrown from a horse in a remote area, and also climbed a steep, snowy driveway to reach a man suffering from a heart attack.

"It's already earned its keep," Buck said.

Richmond may have been the only community in Vermont to vote on whether the police would accept 1033 gear. Buck said residents easily approved the Humvee during a Town Meeting vote three years ago, though some opponents were concerned about militarization. To help allay those concerns, Buck painted it blue and white like a civilian emergency vehicle.

"Most people are silent. They don't care. They support law enforcement," Buck said, then added, "If we get an MRAP, they might question my sanity."

Richmond also received an M14 assault rifle, which has proven popular with local police throughout the state. Middlebury police obtained three, citing concerns about drugs and the need to ensure "balance of firepower" against potential adversaries.

Middlebury Chief Thomas Hanley brought up a 2012 incident in which an armed man called 911 saying that he wanted to be killed by law enforcement. He engaged approaching police in an extended shootout and died in the gunfire.

Hanley said assault rifles allow his officers to keep a distance from whoever is firing at them — which is crucial if they have to exchange fire before the TSU arrive.

"I can't wait hours and hours in a dynamic situation for somebody to deploy," Hanley said. "We're trying to keep our officers safe. I'm not going to put officers in harm's way because somebody might be offended at how they look."

Armed Agencies

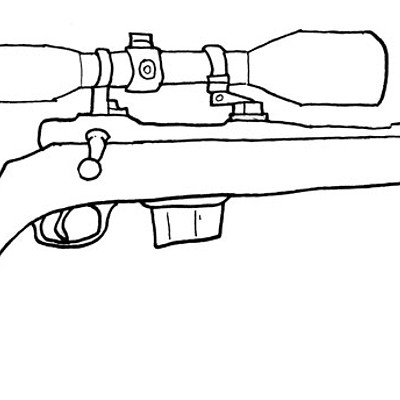

The 1033 Program isn't just for traditional cops. In 1999, the Vermont Fish & Wildlife Department, tasked primarily with enforcing hunting regulations, asked for 30 M14 assault rifles, 10 M21 sniper rifles — which have a range of 900 yards — and 40 shotguns.

With the blessing of then-commissioner Ronald Regan, former chief game warden Roger Whitcomb said, his wardens often helped other officers in emergencies. He recalled one incident, in 1997, in which a northern New Hampshire man killed four people in a town near the Vermont border before dying in a shootout in Vermont.

"Due to the nature of our work, we deal with heavily armed citizens on a daily basis," Whitcomb wrote in 1999, attempting to justify the request.

The application set off alarm bells with higher-ups, concerned that the weaponry might cause a public-relations stir.

In a follow-up letter, Lt. Richard Hislop assured Regan that the requested weapons were not "Rambo-looking." "I hope that you are not receiving, from the public or others, the impression that the warden force is turning into a commando, SWAT team or other militaristic organization," Hislop wrote.

They received only eight M14s. And they haven't seen much use, Fish & Wildlife deputy chief Dennis Reinhardt said in an interview. While freak incidents occur, wardens spend most of their time responding to incidents involving animals, not well-armed criminals. And a military assault rifle isn't really necessary for putting down a moose or a deer that has been hit by a car.

Reinhardt said his department plans to give the weapons back to the military.

Other agencies, including University of Vermont police and the Vermont Department of Motor Vehicles, are looking to get involved in the 1033 Program.

Though they haven't yet obtained any equipment, the UVM Police Department has filed paperwork to join, explaining that the campus "could be seen as a conduit for drug trafficking." The DMV also registered. It recently inquired about acquiring assault rifles for its enforcement officers, though there is no record of a formal application.

Burlington, the largest municipal police force in the state, is conspicuously absent from the list of 1033 beneficiaries.

Chief Michael Schirling isn't against the program. He said his department has been able to purchase high-powered rifles and other gear through its regular operating budget. Schirling said he recognizes the need for other Vermont agencies to receive equipment, and, were he not confident that the state police could respond to a Queen City calamity, he would consider seeking military gear.

Citing concerns raised by events in Ferguson, U.S. Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.) said he wants a review of the 1033 Program. Leahy has not said whether he supports the Stop Militarizing Law Enforcement Act, a Ferguson-inspired bill that would restrict the program and mandate better oversight.

"I do not believe that equipping police officers in our communities — in Vermont or elsewhere — with some of the most sophisticated tools of war keeps us safer on our streets or in our towns," Leahy said in a prepared statement. "Whether through legislative reforms or in the appropriations process, we can do more to ensure the 1033 Program functions as it should, helping police agencies work within tightly constrained budgets while not putting at risk communities' trust in their law-enforcement agencies."

In Orange County, Bohnyak defends the program. The sheriff, who has waltzed to victory every year he has been on the ballot, said citizens must trust that he and his officers will use the weapons as intended — and only in the most dire emergencies.

"Some of it might look scary on paper. I've been with the sheriff's department for 18 years. I've been carrying a patrol rifle. Have I fired a round? No," Bohnyak said. "We need to be vigilant and make sure when the public sees us with this gear on, that they know there's something serious going on, and that we're only using this to protect our officers and our citizens."

Veterans for Peace member Karl Novak, who said he served in the U.S. Navy during the Vietnam War, is uncomfortable with police increasingly resembling soldiers.

"When is it going to end?" Novak said. "They can say all they want, but they're going to find a way to use it. That's the frightening part. Do away with this stuff. Get out of the business of dressing these guys up like the U.S. Army."

The original print version of this article was headlined "Up in Arms"

Related Stories

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

Tags: Politics, armored vehicles, army, assault rifle, cannabis related, community, crime, freedom, humvees, law, Law Enforcement, local police, militarization, military equipment, pentagon, police, sniper rifles, stockpiles, u.s. army, vermont police, vermont state police, Slideshow

More By This Author

Speaking of...

-

Q&A: Downtown Montpelier Transforms Into PoemCity Every April

Apr 24, 2024 -

Video: Visiting the Kellogg-Hubbard Library’s PoemCity in Montpelier During the Month of April

Apr 18, 2024 -

Q&A: Catching Up With the Champlain Valley Quilt Guild

Apr 10, 2024 -

Video: The Champlain Valley Quilt Guild Prepares for Its Biennial Quilt Show

Apr 4, 2024 -

Vermont Supreme Court Suspends Vekos' Law License for Impeding State Probe

Mar 27, 2024 - More »

Comments (5)

Showing 1-5 of 5

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.

- 1. Scott Official Pushes Back on Former State Board of Ed Chair's Testimony Education

- 2. A Former MMA Fighter Runs a Wildlife Rehabilitation Center in Cabot News

- 3. Home Is Where the Target Is: Suburban SoBu Builds a Downtown Neighborhood Real Estate

- 4. Burlington Budget Deficit Balloons to $13.1 Million News

- 5. Vermont Rep. Emilie Kornheiser Sees Raising Revenue as Part of Her Mission Politics

- 6. Legislature Advances Measures to Improve Vermont’s Response to Animal Cruelty Politics

- 7. Dog Hiking Challenge Pushes Humans to Explore Vermont With Their Pups True 802

- 1. Totally Transfixed: A Rare Eclipse on a Bluebird Day Dazzled Crowds in Northern Vermont 2024 Solar Eclipse

- 2. Zoie Saunders, Gov. Scott’s Pick for Education Secretary, Faces Questions About Her Qualifications Education

- 3. Don't Trash Those Solar Eclipse Glasses! Groups Collect Them to Be Reused 2024 Solar Eclipse

- 4. State Will Build Secure Juvenile Treatment Center in Vergennes News

- 5. Vermont Awarded $62 Million in Federal Solar Incentives News

- 6. Queen of the City: Mulvaney-Stanak Sworn In as Burlington Mayor News

- 7. New Jersey Earthquake Is Felt in Vermont News