Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

'Til Death Do Us Part: Maidstone's Grisly Murder-Suicide Was Domestic Violence

Published October 11, 2017 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated November 27, 2018 at 9:34 p.m.

Molly McLain's mother selected the wallet-size photo that was distributed at her daughter's August funeral in Colebrook, N.H. The image was nothing fancy, just a spontaneous selfie the 27-year-old snapped in her kitchen a few months before she died. But it captured everything Amy Benoit wanted to remember about Molly: her big brown eyes and a crooked smile that hinted at the mischievous streak that Benoit always loved about her daughter. The heart-shaped necklace, dangling on Molly's pale skin, was an early birthday gift from her mom.

At home in Pittsburg, N.H., though, Benoit urged a reporter to take a closer look at the picture. It revealed something else about the slain mother of two.

"Look at her left eye," Benoit said. It was ringed by a subtle purple and yellow hue. In June, Molly's husband, Jason McLain, had punched her in the eye. Molly's 4-year-old son, Jack, and 2-year-old daughter, Quinne, called it "Mommy's boo-boo eye."

By the time Molly snapped the picture, the injury was almost healed, and, after years of suffering abuse, she was finally taking steps to leave Jason permanently, Benoit said.

But instead of a new life came a violent death.

On July 26, a month after a judge ordered him to move out and avoid contact with Molly, Jason, 33, burst into their Maidstone house, plunged a knife into her face and shot her with a semiautomatic pistol. Law enforcement officials found Molly's body in a ditch across the street. They located Jason inside the home, dying of a self-inflicted gunshot wound.

Benoit said her grandchildren's clothes were caked in blood when she picked them up at a neighbor's house that night.

While the details of the McLain murder-suicide are shocking, the events that preceded the incident are common to almost every domestic-violence-fueled slaying: a restraining order ignored, a prohibition on firearms flouted, a victim's desire to keep a family together at all costs, geographic isolation, economic insecurity, substance abuse, and a final declaration of independence that enraged a partner and, in Molly's case, caused him to snap.

Domestic violence is one of Vermont's most intractable criminal justice problems, which, for the past 25 years, has fueled a predictable crime stat: Half of the state's homicides result from escalating domestic abuse.

"We ought to be able to get that number down to zero," said Assistant Attorney General Carolyn Hanson, who chairs a statewide commission that studies every domestic violence death in Vermont. "It's a goal we need to be committed to."

But as they process the horror of Molly's death — and the killings of at least two other Vermont women this summer at the hands of their domestic partners — law enforcement officials and advocates acknowledge the trend is not decreasing.

"Each homicide is another moment when we take stock and go, 'Wow, this is discouraging,'" said Auburn Watersong, associate public policy director at the Vermont Network Against Domestic and Sexual Violence. "We look at the criminal justice system a lot for answers, but it's going to take more than that. Until we get at the root of the causes, which involve shifting culture and acceptance of violence ... we may be stuck in not being able to make a dent."

Everyone who has examined the circumstances of Molly's death agrees that she "did everything right," as Vermont State Police Capt. J.P. Sinclair put it, in the weeks leading up to her death. She spoke up. She went to authorities, got Jason out of the house, kept in touch with the outside world, and took steps to permanently break away and support herself.

"She was making plans," Sinclair said. "She was courageous."

In the end, though, that wasn't enough.

'She Wanted a Family'

Molly grew up in Lisbon, N.H., a sleepy town of 1,600 located half an hour west of the White Mountains.

She was a quiet kid who caused little trouble in the house and tried not to get annoyed by her energetic little brother, Dylan, according to her mom.

At Woodsville High School, Benoit said, Molly was an average student who didn't give much thought to college. She had little interest in sports and never aligned herself with a particular group of kids.

Throughout her teenage years, she spent nearly every day with her friend Lindsey Hall. They would talk for hours inside Hall's Woodsville home and, in the summers, hang out by the Connecticut River.

Molly's goal in life, Benoit said, was to become a wife and mother. After leaving high school in 2008, Molly held a series of jobs at convenience stores and started looking for a relationship.

She met Jason on the dating website PlentyOfFish. He had grown up in his family's modest home in Maidstone and spent most of his life in the Northeast Kingdom.

It didn't take long for them to get together. Jason was Molly's first, and only, serious relationship.

"They had the same personality," Hall said. "He was polite. He seemed like a great guy — at the beginning."

Initially, Benoit said she liked her daughter's new boyfriend, too. Jason had a steady job as a janitor at nearby Weeks Medical Center in Lancaster, N.H., and he seemed well-read — he talked excitedly about science-fiction books and psychological thrillers. Molly shared those interests, though hers extended into the mystical realm. She liked to debate whether aliens and mermaids were real and believed in the power of karma and prayer flags.

Benoit saw that Jason made Molly happy.

But from early on, she said, there were troubling signs. Jason seemed arrogant, interrupted Molly often and seemed to have an inflated sense of self-importance.

"He thought he knew everything," said Benoit's partner, Tom Guild, who lives with her in Pittsburg. "You couldn't tell him anything."

Molly quickly moved into Jason's home, which he shared with his father, who died in 2012. Jason's mother, Carole, was not a strong presence in his life, according to Benoit. Neither she nor his brother, James Jr., could be reached for comment.

When Jason and Molly married in March 2011, Molly was working at a nursing home in Lancaster, making $9.50 an hour. She left that job when the couple's first child, Jack, was born in 2013 and never worked again.

Becoming a mother fulfilled Molly's lifelong dream. She doted on her baby boy. "She wanted a family. That was really important to her," Hall said. "She wanted to have the boyfriend, to fall in love, have the happy ending."

Slowly, though, Molly began distancing herself from friends and family. Once inseparable, Hall and Molly went six years without seeing one another, and their online communication slowed to a trickle.

Benoit said that her daughter never revealed the extent of her troubles at home. She would occasionally mention that Jason had a temper, but she wouldn't elaborate.

"She didn't tell me everything. She wasn't a gossipy person — 'We fought; Jason did this,'" Benoit said. "She didn't want anyone to know there were problems."

In court documents filed years later, Molly revealed that Jason had been abusive.

"He had no problem inciting that violence on me while our children were running around playing from room to room," Molly wrote to an Essex Superior Court judge in 2017.

While Benoit said she was unaware of those details in the early years of her daughter's marriage, she had seen enough to become concerned.

Jason drank heavily, Benoit said. Three beers in, the 5-foot-10-inch, 150-pound father of two would start swearing. He also talked openly of abusing prescription pills. Guild remembered Jason once finding a single discarded pill in the back seat of his car. Jason picked it up, shrugged his shoulders and popped it into his mouth.

"Who does that?" Guild said incredulously.

By winter 2014, Molly apparently had had enough. She was pregnant again when she left Jason and moved an hour east, to Littleton, N.H., into a subsidized apartment.

Jason's reaction? According to a statement Molly filed in court, he took everything she left in Maidstone and set it on fire.

Molly obtained a relief from abuse order against her husband in a Littleton court in December 2014. She took that step because Jason raped her, she alleged in a 2017 court filing.

Then, in February 2015, Molly filed for divorce. Records indicate that, at least initially, the divorce was uncontested. In August 2015, the couple signed off on a custody-sharing arrangement. But Jason apparently had second thoughts and decided to challenge it.

Neither Molly nor Jason showed up for a final divorce hearing in July 2016. A judge dismissed the case and never heard from Molly again. She had apparently decided to move back to Maidstone, population 200, to give Jason another chance.

"How do you forgive somebody who burns all your shit?" Guild asked rhetorically. "He sweet-talked her back, saying, 'I won't drink anymore or do any pills.'"

Molly's mom said she understood her daughter's motivation: She wanted her family reunited.

"She felt bad," Benoit said. "She was sympathetic and empathetic and wanted everybody to be happy and Jason to be happy and see his kids."

Returning to an abuser is a common occurrence among battered spouses, according to domestic violence experts. Some studies suggest it takes eight or nine tries to make a permanent break.

click to enlarge

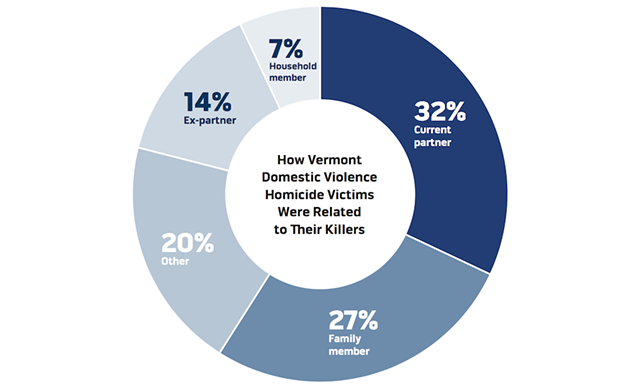

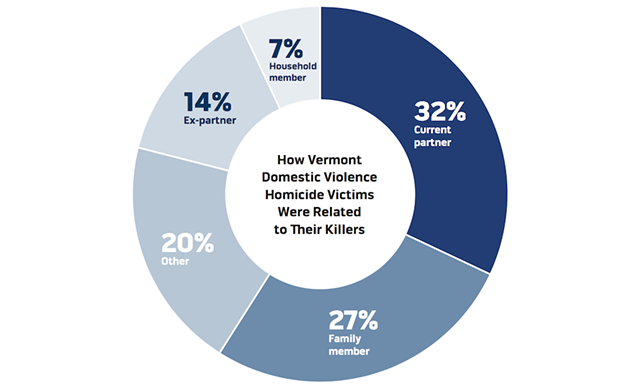

- Source: Vermont Attorney General's Domestic Violence Fatality Review Commission. Data spans 1994-2016.

When Molly returned to Maidstone, she put herself at significant risk. As a full-time mom, she was economically dependent on Jason, who never earned more than $1,600 a month. In 2016, he lost his job and started collecting unemployment.

Molly was also physically isolated. Though the McLains lived on the busiest road in town, Maidstone is in the middle of nowhere, even by Northeast Kingdom standards. No neighbors were visible from their house on Route 102, a one-story ranch set back from the road. The nearest place to socialize was a McDonald's 20 minutes away in Lancaster. The most reliable contact with the outside world came via a cable modem that, in moments of rage, Jason often unplugged, according to court documents.

Now abandoned, the dwelling is surrounded by a picket fence on which someone spray-painted the words, "Love Hotel." A plastic kitchenette and a Cozy Coupe toy car remain in the front yard.

The dangers of such secluded settings are well-known to victim advocates in Vermont, who have long tried to get help to remote areas. For example, Vermont has for the past two decades received a federal grant, the Rural Sexual Assault, Domestic Violence, Dating Violence and Stalking Assistance Program, to increase training for counselors and other supports for children in violent homes in the Northeast Kingdom.

But experts say there is only so much that any government-sponsored initiative can do to overcome geography.

Attorney Wynona Ward founded the Vershire nonprofit Have Justice Will Travel to offer legal aid to people, especially abused women, in rural areas. Many of her clients — a group that included, for a brief time, Molly — experience a heightened sense of despair when stuck in a remote area with an abusive partner, Ward said.

"The isolation adds to the learned helplessness, that there is no one out there to help you, so you begin to believe your spouse is taking care of you," Ward said. "Many times, what I hear from my clients is that they can put up with the physical abuse, but the constant putting down, being told you're stupid and never going to go anywhere in life — all of those things mount up, especially if you don't have contact with a lot of other people."

'There Is Too Much Verbal and Physical Abuse'

Between 1994 and 2016, 49 percent of Vermont's adult homicides were recorded as incidents of domestic violence.

That figure remained largely unchanged even after 2002, when the Vermont legislature created the Domestic Violence Fatality Review Commission to study every domestic violence killing and make policy recommendations to try to prevent future tragedies.

The commission found that four times out of five, men were the killers. Guns were used in nearly 60 percent of the incidents. And, like Molly, 18 of the 137 victims had relief from abuse orders against the individual who took their lives.

Those trends are evident in 2017, too.

Vermont State Police investigators hadn't finished writing up their reports on Molly's case when, a few days later, they were pulled off to investigate another suspected domestic violence murder: Barre resident Randal Gebo allegedly strangled his former girlfriend Cindy Cook in July, then went on the lam for more than a week before he was arrested near Chicago.

On August 27, Rutland resident Randal Johnson allegedly killed his "live-in companion" Trina Fitzgerald during an argument, police said. Johnson is being held without bail after pleading not guilty to second-degree murder.

Roughly a month later, news broke of a possible third case. On October 1, St. Albans police found Leaf Blouin, 51, and the man she lived with, Stephen Puro, 37, dead. Blouin had been stabbed, and Puro had a record of domestic violence. St. Albans police did not respond to requests for further information.

Things started escalating for Molly on June 16, when she called Benoit to say that Jason had hit her, according to court documents. Her mom called 911.

When she arrived at the McLain home, Vermont State Police Cpl. Callie Field immediately noticed that Molly's left cheekbone was bruised, the officer wrote in an affidavit. Molly said Jason had punched her, ramming the rims of her eyeglasses into her cheekbone. She showed Field another bruise, in the hairline above her right eye, that she said was the result of a previous assault.

Molly submitted a four-page, handwritten note to Essex Superior Court explaining what happened. She said Jason stole $50 that her grandmother gave her to spend on the children. He used the money to buy 12 Percocets, Molly wrote.

Upset, she said she wanted to take the kids to visit Benoit in Pittsburg. As the children napped, their parents argued. Jason said Molly would not be allowed back in the house if she left, and he would again burn her belongings.

Then he took her keys and phone, shut off their modem, and punched her in the face. Molly was eventually able to get to the phone and call Benoit.

By then, Molly had opened up to her mom about what was happening with Jason. The mother and daughter had grown closer and spoke nearly every day. Benoit urged Molly to take steps to leave Jason, who would eventually blame Benoit for their final separation.

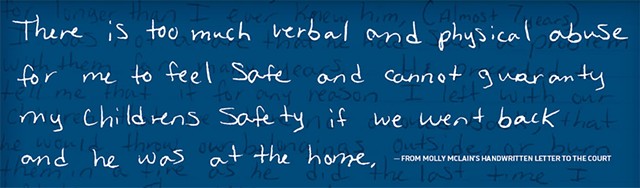

"There is too much verbal and physical abuse for me to feel safe, and [I] cannot guaranty my childrens safety if we went back and he was at the home," Molly wrote in her report to the court.

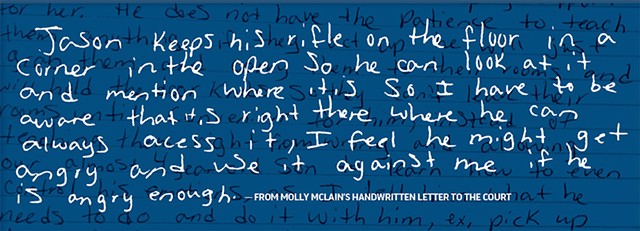

She ended it on a chilling note: "Jason keeps his rifle on the floor in a corner in the open so he can look at it and mention where it is so I have to be aware that it is right there where he can always access it," she wrote. "I feel he might get angry and use it against me if he is angry enough."

Jason denied assaulting his wife when interviewed by police in June. He said that Molly had pushed him, though he later amended that accusation to say that she "brushed by" him. Police arrested him, and a judge allowed him to remain free, pending his court case.

Essex County State's Attorney Vince Illuzzi charged Jason with two misdemeanors: domestic assault and interfering with emergency services. Jason had no criminal record and had deep ties to the community. He posed almost no risk for flight, and so could not be subjected to bail, Illuzzi said in an interview.

"I don't know what I could have done differently," Illuzzi said.

On July 10, Jason pleaded not guilty. Judge Elizabeth Mann released him without bail, on conditions that he stay 300 feet away from Molly and the children.

On the strength of her letter, along with her visible injuries and the police affidavit, Molly also secured a restraining order against Jason as the criminal case was pending. She was awarded sole possession of her home for one year, to give her a chance to rebuild her life without worrying about where her kids would live.

The judge also ordered Jason to surrender his rifle, which remains, to this day, in an evidence locker inside the Essex County Sheriff's Department.

Over the years, victim advocates have proposed policies to make it easier for police to seize and store firearms from alleged domestic abusers. Their efforts came after several cases in which killers got their hands on weapons when a judge had ordered them not to.

Essex County Sheriff Trevor Colby suggested that the language in court orders ought to be tougher. Judges should not only forbid people from possessing firearms, he said; they should ban defendants from living inside homes with firearms.

"For anybody who has a propensity for violence, it's not enough to just say, 'Shall not possess,'" Colby said. "I asked Jason if he had any other firearms. He said, 'No, I haven't been home; whatever you guys took is what I have.'"

In the end, police believe Jason stole the murder weapon from a friend who had given him a place to stay, according to Capt. Sinclair.

Breaking Away

Benoit said she had never been more proud of her daughter than in the weeks after the court orders were issued.

Molly became more talkative and smiled easily. She began reaching out to old friends, mostly through Facebook.

Hall, who hadn't seen her friend in six years, said she was overjoyed when she and Molly began trading daily Facebook messages during the summer.

In July they met up in Bradford, where Hall was throwing a birthday party for her 2-year-old daughter. The old friends' children met for the first time, and Molly seemed excited about her future, Hall said.

"She was happy — genuinely happy," Hall said. The two planned a playdate for their kids and, at Molly's insistence, snapped a few pictures together.

In the months before she died, Molly explored the possibility of enrolling in a nursing school and visited at least one to talk to an admissions counselor, Benoit said. Though a judge had granted her exclusive use of the house for a year, Benoit said her goal was to move within six months. She even went out on a couple of dates with an old friend from high school.

This time, her mother said, Molly was determined to leave Jason for good. That resolve brought her perilously close to what victim advocates describe as the cruel irony of domestic violence: Victims need to break away to be safe and yet are at their most vulnerable when they do.

"That is very real," said Abby Tasell, assistant director of the Upper Valley domestic abuse organization WISE. "When we're talking about this as one person controlling another person, the ultimate lack of control is when the victim starts to make moves to get away. This is the time that violence often escalates."

On the day she was killed, Molly drove with her kids to Pittsburg to spend the afternoon with her mother. They laughed and chased the kids around the yard and planned for Molly's future, Benoit recalled.

As evening neared, Benoit said that Molly seemed reluctant to leave. But the kids were eager to get home, so she bid her mother goodbye and drove to Maidstone.

She and her mom continued to communicate that evening.

"I love u and it will all turn out OK," Benoit texted Molly at 6:52 p.m.

"Hey, I know, it's just hard to keep that focus but thank you so much, we just got home," Molly replied.

"I notice that when I think good things, good things happen...hard...but worth it," Benoit texted back.

It was the kind of conversation the mother and daughter had been having frequently in the past year. They had grown closer, Benoit said. She had sewn a prayer flag and given it to Molly to keep watch over her.

"I know, thank you, I need another prayer flag lol," Molly replied.

"Oooh what a good idea," Benoit said.

"Ya, put extra love in it lol I love u, ur awesome."

Those were the last words Molly ever shared with her mother.

Sympathy for the Abuser?

Is there a better way to deter domestic violence in Vermont?

"If you asked me 20 years ago, I'd say: enhance penalties and lock them up," veteran prosecutor Illuzzi said. "But there's another school of thought that says we have to be sensitive to who he is, too. People see doors closing and not a lot of light at the end of the tunnel, and they snap."

Much like criminal justice reformers have urged policy makers to think of drug abuse as a health problem and not a crime, domestic abuse experts are starting to call for alternative approaches to keeping victims safe — and to looking after their abusers.

Gwen Lavoie, who recently departed after several years as head of a Franklin County shelter and advocacy organization, suggested that the state devote more resources to hiring social workers and clinicians and require counseling for both victims and abusers.

"These things are just so delicate and bizarre. Asking cops to walk cold into this crazy situation and figure out how to help a family move forward is just ludicrous," Lavoie said. "I would love to see us do lots more work with women and their children afterward. And batterers. Let's stop treating them like criminals and treat them like humans who need help. We don't work with them to help them understand what a real relationship looks like."

As he looks back on the Maidstone case, Illuzzi said he wondered if pressing charges against Jason somehow made things worse.

"To someone who doesn't have a lot of good things going on in their life, you isolate the person, take away their house, their wife, their kids — they break," Illuzi said. "That's what happened in this case. Jason broke. You look at the system — the participants did what they were supposed to. I don't know what an alternative response would look like."

Benoit said she wishes Jason had been held in jail on bail, even for a few days, to scare him straight.

Ultimately, though, she doesn't blame the criminal justice system for Molly's death.

"If somebody is wanting to get you, they're going to get to you," Benoit suggested. She said she tries not to dwell on what happened. Raising Molly's two children, when she had expected to be retiring, keeps her focused.

But her thoughts drift often to that night and her final conversation with her daughter. Police seized her iPad as evidence, she said, and have yet to return it. But she can still access the text messages from her partner's iPad. As Molly's kids ran back and forth on her porch, Benoit pulled up the texts.

At 7:54 p.m., less than an hour after Benoit and Molly exchanged their final text, Jason texted Benoit from Molly's phone.

"I murdered your daughter. And killed myself. Kids selle with s neighbor. I never hit herel. You know that. You planned it with her. You did this, with her. Hiw could yiu? I was a good man. I worked 7 years she worked 6 months. You told her what to do. This is on you. How's her new boyfriend feel?"

Benoit said she initially thought — or perhaps hoped — Jason was joking. Then she called him, and, in the moments before shooting himself, he said again, "I murdered your daughter."

Benoit called the police. They had already received reports from neighbors who'd heard gunshots. Then Benoit sped to Maidstone. The normally hourlong trip took about half as much time, she remembered.

Colby, the Essex County sheriff, was also speeding to Maidstone. He had been on patrol in a nearby town when a dispatcher notified him of a 911 call from a resident there. No one offered any specifics, but Colby had a hunch about what had happened.

Jason had parked his truck up the street, barged into the home and, with their children inside, attacked his wife.

Police found Jason on a living room couch with a hole in his head. He had a pulse and was taken to Weeks Medical Center and later to Dartmouth-Hitchcock in Lebanon, N.H., where he was pronounced dead the next day.

After finding Jason, police began frantically searching the house and yard for Molly. They eventually found her in a ditch across Route 102 from her house. She, too, had a pulse but was pronounced dead that night at Weeks.

In the hours after the call, cops from several law enforcement agencies, including the Vermont and New Hampshire state police and the U.S Border Patrol, descended on the area. They congregated in the conference room inside the Essex County Sheriff's Department in nearby Guildhall.

As the cops milled around the room, Colby noticed a card with a drawing of small birds sitting on the conference room's main table.

Molly had brought it by a few days earlier, along with a tray of brownies, to thank the sheriff's deputies for their help.

"Many thanks for being so nice," it read. "From Molly and the children."

Related Stories

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

More By This Author

Speaking of...

-

'I Felt Safe': Steps to End Domestic Violence Gives Survivors Hope for a Better Tomorrow PAID POST

May 25, 2022 -

Former Vermont Trooper Charged With Striking Puppy, Perjury

Apr 19, 2022 -

Advocates Fear Surge of Domestic Violence Cases in Vermont

Mar 27, 2020 -

Two Recent Cases Put Vermont's Domestic Violence Laws to the Test

Mar 4, 2020 -

Winooski Cop Denies a Slew of Domestic Violence Charges

Feb 20, 2020 - More »

Comments (5)

Showing 1-5 of 5

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.

- 1. UVM, Middlebury College Students Set Up Encampments to Protest War in Gaza News

- 2. Dog Hiking Challenge Pushes Humans to Explore Vermont With Their Pups True 802

- 3. Scott Official Pushes Back on Former State Board of Ed Chair's Testimony Education

- 4. Governor Makes Last-Minute Appeal to Delay Vote on Ed Secretary Nominee Education

- 5. A Former MMA Fighter Runs a Wildlife Rehabilitation Center in Cabot News

- 6. Burlington Budget Deficit Balloons to $13.1 Million News

- 7. Home Is Where the Target Is: Suburban SoBu Builds a Downtown Neighborhood Real Estate

- 1. Totally Transfixed: A Rare Eclipse on a Bluebird Day Dazzled Crowds in Northern Vermont 2024 Solar Eclipse

- 2. Zoie Saunders, Gov. Scott’s Pick for Education Secretary, Faces Questions About Her Qualifications Education

- 3. Don't Trash Those Solar Eclipse Glasses! Groups Collect Them to Be Reused 2024 Solar Eclipse

- 4. State Will Build Secure Juvenile Treatment Center in Vergennes News

- 5. Vermont Awarded $62 Million in Federal Solar Incentives News

- 6. Queen of the City: Mulvaney-Stanak Sworn In as Burlington Mayor News

- 7. New Jersey Earthquake Is Felt in Vermont News