Published October 3, 2007 at 2:46 p.m.

Great theater reaches across the footlights and elicits a visceral response. This genuine stage magic is infrequent. But occasionally the alchemy of writing, acting and subject matter is so electrifying that no one experiencing it can remain a detached observer.

Athol Fugard's "Master Harold" . . . and the boys grabbed me by the throat when I first saw it 25 years ago - the play became personal. This week Weston Playhouse brings the landmark work to three northern Vermont venues.

At 75, Fugard is considered one of South Africa's literary elder statesmen. But under the apartheid regime, the white playwright endured harassment, censorship and even the temporary revocation of his passport. Putting on his plays - even underground, as he often did - became increasingly difficult. He wrote for mixed-race casts, and theaters faced the same rigid segregation laws that governed every aspect of public and private life.

The playwright refused to go into exile, citing his troubled but beloved country as the lifeblood of his writing. Some of Fugard's colleagues, such as actor Zakes Mokae, did choose to leave. Black artists lived under the constant threat of imprisonment and torture for trumped-up violations of the repressive regime's rules, but Fugard's growing international reputation protected him. The government "realized it would be wiser to leave me alone, even though I was an irritant, because the adverse publicity . . . would outweigh any benefits," he reflected shortly after apartheid's fall.

Although Fugard continued to write in South Africa, it became clear by the late 1970s that he needed to stage his works abroad. It was the only way to keep writing integrated plays on challenging themes and see them fully realized on stage, in collaboration with favorite, now-exiled, longtime associates such as the London-based Mokae.

In the United States, Fugard began working closely with Lloyd Richards, who had broken Broadway's color barrier in 1959 when he directed Lorraine Hansberry's A Raisin in the Sun. In '79, Richards became dean of the Yale School of Drama and director of its Repertory Theater. He made Yale a home to playwrights who confronted difficult issues, particularly race. Two of his most productive relationships were with Fugard and August Wilson, then a little-known African-American playwright whose work Richards helped bring to national prominence. During Richards' 12-year tenure at the Rep, Fugard directed more than half a dozen of his plays. A trio of the Yale productions went to Broadway and ultimately garnered Tony Awards.

"Master Harold" was the first Fugard play to make its world premiere outside South Africa. Unlike many writers who coyly avoid questions about creating fiction from fact, Fugard frankly admits he draws stories directly from real life. "Master Harold" is Fugard's most autobiographical play. Published diary entries show he used names of real people and places, and the confessional details are both heart-warming and gut-wrenching. Based on something that happened when Fugard was 13, the play is an exercise in self-exorcism. "Don't suppose I will ever deal with the shame that overwhelmed me," he wrote in a 1961 journal entry.

And yet, 20 years later, he put that shame on stage. He turned a transient episode of childhood ugliness into a play of enduring power and beauty.

The tale takes place on a rainy afternoon in 1950, in Port Elizabeth, Fugard's hometown on South Africa's Eastern Cape. There are no customers in the somewhat shabby St. George's Park Tea Room. Employees Sam and Willie banter about an upcoming ballroom dancing competition while doing their routine cleaning tasks. The owners' son, 17-year-old Hally, comes by after school and joins in the verbal jousting. As the three joke, laugh, and recall old stories, it becomes clear that the two older black men and the young white boy have a long history together. The family servants are Hally's real family.

A phone call brings news that ruptures Hally's good mood. His crippled, alcoholic father is coming home from the hospital, and Hally dreads the disruption. He's spent most of his life caring for the demanding, drunk invalid. Hally's frustration rises as he fails to talk his mother into keeping the old man in the hospital.

Sam tries to calm the agitated adolescent, but Hally lashes out. He can't vent his anger on the pathetic father who isn't there. And so the gentle, patient and loving surrogate father who has always been there for the young boy becomes the teen's target. When Hally threatens to play the race card in their relationship, all three men know it's the one thing he can never take back.

*************

When "Master Harold" opened at the Yale Rep in March 1982, I was a freshman. The Rep offered dirt-cheap season tickets to undergrads, and I subscribed - my first experience with the stage, beyond high-kicking it in the chorus of "New York, New York" for the senior variety show in high school.

I was a naïve blonde from multicultural Honolulu. Hawaii's two-century tsunami of Asian, European and Pacific immigration ensured that no ethnic group held a majority, and many individuals' ancestry was a veritable global stir-fry. The greatest shock of coming to the mainland for college was discovering that racism and prejudice still thrived, even in the supposedly liberal Northeast. I had studied the civil-rights movement in American History class. I thought racism was history, as in over.

Yale was an island of privilege in New Haven's struggling inner city. The white population had long since fled for the suburbs, so town-gown tensions took on uneasy racial undertones. I was appalled that stereotypes went largely unquestioned among my classmates, who came from all over the country. Dining-hall tables magically "self"-segregated. Because my dates and crushes sometimes included men of color, one roommate teased me relentlessly about having a "thing" for black men. To me, it seemed ridiculous when I learned that many people never considered dating outside their race. In Hawaii, this would have led to a population crash!

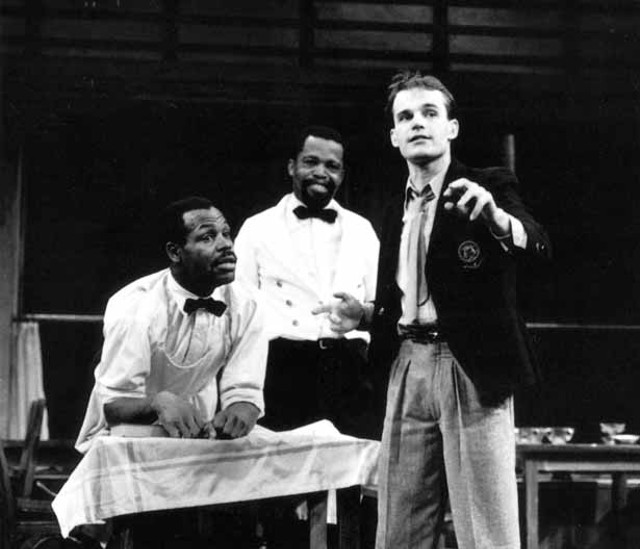

So when I put aside my Latin homework and settled into my seat on that cold spring night to see "Master Harold," my halcyon assumptions about racial harmony were already in turmoil. Zakes Mokae played Sam. Danny Glover portrayed Willie. Zeljko Ivanek was Hally.

I left the theater stunned. How can skin color come between people who love each other? It was a concept far outside my experience. Fugard's indictment of apartheid is so searing precisely because this is not a political play. And yet racism's corrosive effects seep into the quiet tearoom and eat away at a family. Society not only dictates twisted laws but can also twist people's hearts.

************

Master Harold" naturally affects not just impressionable young theatergoers but actors, directors and producers as well. Participants in the current Weston production share some vivid recollections of their first contact with Fugard. Actor Guiesseppe Jones, who plays Sam, first encountered the play when he was cast as Willie for a 1991 production in Nevada City, a small northern California town. "The most intense part about the experience was that some season ticket holders turned in their tickets because they didn't want to see a play with black people in it," he recalls. (Twenty-five of 700 subscribers canceled, according to The New York Times.) Despite the controversy, "the show eventually wound up being a huge success," Jones remembers, with community support leading to sold-out performances and standing ovations.

Weston Producing Director Steve Stettler saw the original production in 1982 when it came to Broadway. Lonny Price had taken over the role of Hally. At the time, Stettler was a teacher and a graduate student. "I remember being completely blown away by the play," he says. "It's remained [a] very strong image of an unforgettable night in the theater for 25 years."

A Weston patron who had also seen the show in its first Broadway run called Stettler "out of the blue" to relay how "this play remains so strong in [her]," he says. This passion fueled her to raise funds to bring several busloads of students and faculty from Northfield-Mount Hermon School in Massachusetts to see it this year in Weston. "It's the kind of play that grabs hold of you and doesn't let go," Stettler remarks.

For director Hal Brooks, staging "Master Harold" at Weston is his first immersion in Fugard. He explains how his own college experiences deepened his connection to the play. "I remembered very vividly, while approaching this material, the divestment movement at Yale," he says. (In the mid- and late '80s, students advocated purging university endowment portfolios of companies doing business in South Africa.) His friends helped build a symbolic shantytown on campus. "I looked at it with admiration, but I was not part of it. I very much sat on the side and watched," Brooks notes.

"The police went in very early one morning and tore down the shanties," he recalls. His activist friends suffered serious consequences in the subsequent protests and clashes with authorities. "I remember thinking, 'Wow, it's amazing that these folks have put themselves on the line for this.' And . . . that's exactly what [Fugard] is talking about at the very end. He's having Sam say to Hally, 'You don't really have to sit on the sidelines. You can do something. You don't have to sit on that apartheid, Whites Only bench.'"

"That was my point of connection," Brooks continues. "To not be that person who sits along the side, or to not have the audience be those people who sit along on the side and say, 'Oh, that's really bad,' but actually to do something. Now I don't know if that means storming the bursar's office, but it certainly means maybe taking a more active step than I was willing to take at that age."

*************

In 2007, the play continues to connect with young people. Weston's "Master Harold" received an "overwhelming response," says Stettler, from its school matinee audiences - numbering more than 1000 middle and high school students. He found that the kids readily identified with teen protagonist Hally. Jones believes "the student audiences were some of the best audiences . . . They get that these three guys have a wonderful relationship, and that it goes askew . . . And I think that's the heart of the play."

Also at the heart of the play, for me, is a question Sam asks. The ballroom competition preparations continue as the story unfolds, and Sam uses collisions on the dance floor as a metaphor for how people are always "bumping into each other" in life. At the end he asks, "Are we never going to get it right?" Sam poses the question in a broad context, but the elephant in the South African tearoom is, of course, race.

My naïveté on that subject is long gone, and two or three news stories crop up every week to flog my remaining optimism into submission. Racism remains the elephant in many rooms of American society.

Toward the end of my conversation with Guiesseppe Jones, I indulge in some freewheeling speculation. My pet theory: South Africa's post-apartheid Truth and Reconciliation process might just give that country - despite the rawness of its wounds - a faster shot at healing. In the book No Future Without Forgiveness, Archbishop Desmond Tutu asserts, "To forgive is indeed the best form of self-interest, since anger, resentment and revenge are corrosive of that . . . greatest good, communal harmony." Jones acknowledges that, in America, "I don't think we want to confront. And we don't want to forgive."

Readers should be skeptical of anyone christening something a "must-see." But there is a stunning moment toward the end of "Master Harold" - and if you see it, you'll know exactly which one I mean - that I can picture as clearly today as when I saw it a quarter-century ago. Fugard taught me something about myself, about how strongly I feel. It's a rare moment in theater, or in life, that does this, and it's one I still cherish.

Info:

"Master Harold" . . . and the boys, directed by Hal Brooks, produced by Weston Playhouse Theatre Company. Dibden Center, Johnson State College, Johnson, October 3, 7:30 p.m.; Chandler Center, Randolph, October 4, 7:30 p.m.; Flynn MainStage, Burlington, October 5, 8 p.m. See calendar in Section B for prices and other info.

More By This Author

Speaking of...

-

Executive Director Kurt Thoma Leaves Barre Opera House

Mar 5, 2024 -

Vermonter's Musical Bound for Broadway With Hillary Clinton as a Producer

Oct 25, 2023 -

Phantom Theater Finds New Winter Venue in Waitsfield

Oct 13, 2023 -

Double E 2023 Summer Concert Series Kicks Off With the Wailers

Mar 17, 2023 -

Off Center for the Dramatic Arts to Reopen in the New North End

Sep 23, 2022 - More »

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.