click to enlarge

- Courtesy Of Beowulf Sheehan

- Stephen P. Kiernan

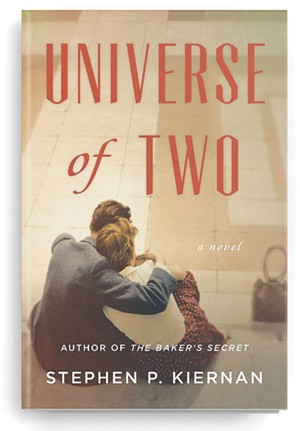

In Universe of Two, Vermont novelist Stephen P. Kiernan fictionalizes real-life Charles Fisk, a young American mathematician ordered to work on the Manhattan Project — the research during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. Charlie Fish, as he's called in the novel, is a sensitive lad set to graduate from Harvard University at age 18, until his uncle sends him to Chicago to work on mysterious calculations for the military.

In Chicago, Charlie meets Brenda, a headstrong and talented organist who considers herself out of his league. After a meet-cute in the music store her family owns, the couple begins a long courtship that gets interrupted by the secrecy of Charlie's work: In order to prevent espionage, his job is compartmentalized, and he has no idea that his math ultimately will contribute to the slaughter of several hundred thousand civilians.

That is, until Charlie is swept off to Los Alamos, N.M., where he's nicknamed "Trigger," and he slowly comes to realize that he's solely responsible for building the atomic bomb's detonator.

Kiernan broadens this already fascinating premise by switching back and forth from Charlie's to Brenda's perspective, which gives the novel a whole new dimension. Too many war stories are told from a male soldier's point of view, so it's refreshing to get a glimpse into her psyche.

Brenda's endless supply of folksy idioms can be wearying, but she feels authentic as a character. She's assertive, tender, occasionally deceptive, but always empathic and self-aware. Really, Brenda is more complex than Charlie, whose emotional range is limited mostly to self-doubt — which is surprising for someone capable of graduating from Harvard in his teens.

Brenda's narration itself occurs on two levels: both telling the story as it happens and commenting on it as an elderly woman at an assisted-living facility. She recalls her youthful mixture of trauma and desire à la Rose in the film Titanic. The book's opening paragraph hooks the reader immediately:

I met Charlie Fish in Chicago in the fall of 1943. First I dismissed him, then I liked him, then I ruined him, then I saved him. In return he taught me what love was, lust, too, and above all what it is like to have a powerful conscience.

True to its title, Universe of Two succeeds at presenting both Charlie and Brenda as complex equals; some authors might have reduced her to a minor character fretting on the sidelines during the man's "hero journey." Brenda has her own share of secrets, and she pressures Charlie to conform to the masculine standards of the day. After the war, she blames herself for nudging him, however inadvertently, while he faced a moral crossroads.

click to enlarge

- Courtesy

- Universe of Two, by Stephen P. Kiernan, William Morrow, 448 pages. $27.99

Ultimately, both of them struggle to make sense of their decisions. In this way, Kiernan's fourth novel is consistent with a popular trend in contemporary fiction in which stories that likely would have been told from a single perspective even 10 years ago are now enriched by multiple points of view. Ben Lerner and Rachel Kushner's latest novels, The Topeka School and The Mars Room, respectively, come to mind.

Occasionally, Kiernan makes odd choices that might pull some readers out of the world he's creating. The story is meticulously researched, yet one of Charlie's comrades in the electronics department is known as "the walking dictionary," and throughout the book he ruminates on the definitions of words such as sonder, liberosis and chrysalism.

"Where do you find these ten-cent words?" Charlie asks. "Lying on the ground, Charlie, waiting for someone to scoop them up," he answers.

But some readers will realize the author scooped them from the internet: These words are all recent neologisms coined by poet John Koenig for his popular Tumblr page, Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows (a book version is forthcoming from Simon & Schuster).

History buffs — and pedantic critics — might be irked by these occasional anachronisms, but most readers will likely let them go and simply enjoy this wartime love story as it unfolds. After all, Universe of Two is neither textbook nor biography but a reimagining that stays true to its historical setting as it invents a vivid personal history for its characters.

The true story of Charles Fisk's life is proof that, sometimes, regular people find themselves thrust cinematically onto the stage of major events — in this case, the development of the atomic bomb. The choices they make there may not alter the course of humanity directly but do contribute to it. And afterward, they must choose how to process their complicity.

After the war, Charlie's guilt spirals dangerously, and he tattoos himself with the numbers of casualties he considers his. Though it means sacrificing her dream of performing as a musician, Brenda gives Charlie the courage he needs to abandon his physics career. The two of them embark on a new life together, building instruments instead of weapons. C.B. Fisk, a company that the real Charles Fisk founded, still exists today — one of its pipe organs can be found inside the University of Vermont Recital Hall.

Kiernan does an excellent job of demonstrating the ethical wrestling match that took place between scientists and the military during the Manhattan Project; interested readers can go on to explore the sources to which he alludes, such as the dissident Franck Report, which American high school history teachers rarely mention.

The novel stops short of using the word "genocide" to describe the U.S. bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki (the 75th anniversary of which is this week), but it reveals the cold-blooded calculations that went on behind the scenes before the bomb's use. There's a distinctly swords-into-ploughshares quality to Fisk's role in history — or rather, bombs-into-church-organs. Charlie and Brenda's choices imply that harmony (in music and in love) can be every bit as powerful as splitting the atom. It's a history lesson contemporary leaders would do well to remember.