Published May 14, 2008 at 11:51 a.m.

The Shelburne Museum opens for the season this weekend with an olfactory rush: “Lilac Sunday” is nearly as renowned as the museum’s vast cache of folk art and artifacts. But the glory of spring blossoms is brief, while the new exhibits, along with the permanent collections, will be on view through October 26. That’s a generous expanse of time in which visitors can — and should — see what the Shelburne is up to now.

Anyone who thinks the museum is frozen, however beautifully, in antiquity hasn’t been paying attention. In the past couple of years, director Stephan Jost has brought about a veritable sea change, addressing the question, “How can a museum stay relevant and appealing?” with boldness, verve and good humor. The trick is making compelling connections between past and present; after all, history is always being made, and artists continue to respond to it. And make it.

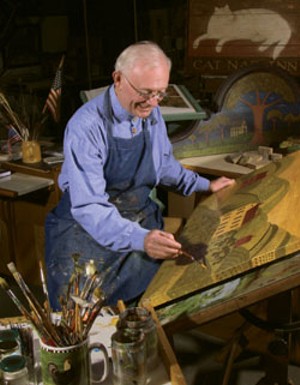

That includes Warren Kimble. Yes, the highly successful Vermont folk artist famous for his serene Americana. Who would have thought Kimble would also create works that are contemporary in style, deeply poignant and blatantly antiwar? Yet he has. The “Widows of War” paintings and installation pieces are part of his Shelburne Museum debut, a retrospective titled “Warren Kimble’s America.” In contrast with Kimble’s quaint animals and rural scenes, the “Widows” works are in stark black-and-white with dashes of blood red and occasional barbed wire. They employ spare symbolism — clothespins, dressmaker’s mannequins, fabric-like patterns — to portray women stricken by loss.

Viewing all the works together, it’s easy to imagine their appeal to Jost: The exhibit presents several past-and-present overlays. There’s the continuum of Kimble’s development as an artist; the faux-vintage aspect of his folk art and the sense of history it evokes; the folky techniques and humble imagery used in the contemporary works. For the art historian and casual viewer alike, the show is rich in meaning.

But Jost justifies his choice in another way: “I take the sentimentality of American folk art very seriously,” he says. “There’s something about our culture that loves that.”

Kimble himself intuitively grasps that, in the fast-moving, technology-obsessed modern world, many people enjoy images that speak to a slower, less complicated time — even if it exists only in fable. In a phone conversation last week from his home in Brandon, the artist spoke about life, death, community and cheerleading.

SEVEN DAYS: How does it feel to have this retrospective at the Shelburne Museum?

WARREN KIMBLE: I’m extremely honored. This is kind of the culmination of an art life. It’s overwhelming to me, because I’ve been going to the museum for every one of the 38 years that I’ve lived in Vermont . . . To be there in this space and this time of my life is just a great gift.

SD: Your work and other contemporary folk art are contiguous with the collecting passions of [museum founder] Electra Havemeyer Webb. Yet it seems there’s a bias in the art world that “folk” art has to either be from, say, a century ago or created by a so-called “outsider” artist to be “authentic.” Have you found that to be true?

WK: Well, it hasn’t affected me, because of the licensing and publishing. I’ve found that wealthy America and poor America can afford my work and like it. They don’t care that I’ve been trained.

SD: Along the same lines, you’ve been wildly successful commercially . . .

WK: Oh, well — it sort of happened late in life, which is another gift. All artists have to have someone help them, and I have a wonderful wife [Lorraine], who’s the CEO and an incredible help. I’ve lived in Brandon 38 years, and the success, hopefully, didn’t change me.

SD: What are your biggest sellers?

WK: Well, a couple of calendars and a lot of stuff by Lang Company — notecards and all kinds of paper goods. But the house on the hill with the flag and the swing has probably sold the most

. . . The cow with the State of Vermont on it — that was one of the first ones to take off . . .

SD: So I can buy a Warren Kimble reproduction poster for under 20 bucks. What’s the price range for original paintings?

WK: Now, about seven or eight thousand to 20,000.

SD: I know you were born in 1935 in New Jersey. Fill me in a bit — were you interested in art from childhood?

WK: Very much so. My parents were only eighth-grade graduates, but they encouraged me. My brother, who died last summer, was 11 years older and was a professional dancer on Broadway. Because he was older — and my mother was a show-biz mom — I was allowed to just do my artwork . . . My mom died when I was 16.

SD: Where did you get your training?

WK: I got into Syracuse not knowing anything about it. I applied and got in — I hadn’t even taken the SATs. The principal of my high school wrote me a good letter, I sent in the application, and Syracuse took a chance on me. That’s one of the things that made my life and got me to this point. I went there four years and did well. I was a cheerleader, the head for three years, was president of my class the last two years. John F. Kennedy gave me my diploma.

SD: When did you teach at Castleton State College?

WK: I worked in advertising in New York and New Jersey and Florida, then went into teaching in 1962-ish — with no credentials — in elementary, junior and senior high in New Jersey. I moved to Vermont in 1970 and got a job at Castleton.

SD: I saw a few examples of your painting from that period at the Shelburne. How would you describe your style, and your artistic interests, at the time?

WK: I was a watercolorist, painting Queen Anne’s Lace and rural scenes. I was also making wooden marionettes and dollhouses for women collectors. When you teach art in a small college, you teach everything. I taught printmaking, design, sculpture, figure drawing, graphic design, teacher education

. . . My wife said you should focus on something so you can be successful.

SD: How did the transition to a folk style come about?

WK: I actually started in 1962 when I was teaching in New Jersey, but it wasn’t the right time or place. When I started again about 1987 with the folk art, it became the right time and place. Wild Apple Graphics [in Woodstock] found me in a local show — they asked to take my work to a [New England craft] show, and that’s when it just exploded . . . When artists come to me and ask, “How can I be as successful as you?” the first thing I say is, you never know . . . It’s luck, how hard you work, the timing, the mood of the nation.

SD: Were you influenced by any other artists or folk traditions?

WK: The museum was a great influence, and being in the antiques business. Jasper Johns was an influence. Norman Rockwell. There are so many artists that are better than you are, you must respect and admire them and learn from them.

SD: I didn’t know you were in the antiques business.

WK: Yes, I did it while teaching. It was a love — I call it legalized gambling . . . You buy something, make enough money on it to buy something else.

SD: Your style is very wholesome, very mom-and-apple-pie Americana, reflecting what we like to think of as a simpler, easier time. Why do you think that resonates with people?

WK: It’s interesting. That’s where we are in Vermont — you think of Vermont as being simpler, a calm quality of life, and it is. But people around the world seek that also. That’s why I think my work is popular in New York City, in London, in Australia . . . My work may say “America” if I put a flag in it, but if it’s just trees, it has that serenity . . . If it makes people feel good, it’s OK.

SD: Along with many whimsical and charming pieces in the Shelburne show, there are some very different works. I have to ask you about the painting “Chris’ Star.” Even without knowing its significance, it’s quite evocative. Is this the first public showing of that piece?

WK: Yes. I had three children, and Chris was a writer in New York. He contracted AIDS in the early ’90s. I went to the Vermont Studio Center, which I do every year . . . It was my way to work with it within me. I remember when my brother was in the service, the star in the window. No, Chris was not in a war, but this was another kind of war . . . a war on health. [Chris died in 1991 at age 29.]

SD: Does the exhibition of this painting represent a coming to terms with his death, or did you decide to include it in a kind of biographical vein?

WK: It was a part of my life . . . I’ve lived with that painting in my studio and see it every day. Most people don’t know what it’s about.

SD: To me, that painting, especially as your exhibit in the Round Barn “reads” in chronological order, signals the “Widows of War” series — in a psychological sense. Both are about traumatic loss . . . This is a retrospective, so, in retrospect, do you feel there’s a parallel or kinship between the two?

WK: There is more than the window image. How the “Widows of War” started: I was at [the VSC] for a month. two or three years ago. and came back to the studio one night after dinner. I’d purchased one of the mannequins and was going to paint folk art on it. I put it in front of the window. I turned on the radio and heard that two more guys had been killed in Iraq. I looked at that mannequin and I thought, My God, that’s a woman! She’s standing in front of the window, wondering, Where am I going, what am I going to do in my life? I started painting on paper, did two paintings immediately . . . I had canvas and gesso. I started ripping up canvas . . . The latest one is the mannequin with the barbed wire . . . The majority of the work was done in a two-year period, but it’s not over. It’s my reaction to [the Iraq] war specifically, but it could be any war.

SD: Many viewers are going to be surprised — except the ones who read this article first — at the “Widows of War” pieces. Some may even think you’re making an unpatriotic, antiwar statement. What would you like those viewers to know about these works?

WK: Antiwar means you’re not in love with war. Who is? I don’t think anybody wants war — or if they do, they have a problem

. . . I’ve not had one adverse reaction. It’s not saying anything that isn’t true . . . This is my way of giving my opinion of what war can do to families. There are widowers, too, but I haven’t gotten into that yet.

SD: Let me switch gears and ask you about being “Mr. Brandon, Vermont.” You have been extremely active in the town . . . and are on quite a few boards —

WK: I have worked with [the chamber of commerce] 38 years. I founded the Brandon Artists Guild. But I’ve always done this . . . You have to give back when you’ve been given. I am on a lot of boards . . . the board of trustees of Green Mountain College. At Syracuse I’m on the alumni board, the visual and performing arts board. I go to a cheerleader reunion every year . . . It’s a great giving, but it’s also a great getting.

SD: You’ve been very instrumental in bringing the so-called creative economy to Brandon . . .

WK: Well, we’ve tried. A lot of people have been involved. The town was pretty worn out . . . but young people have been able to buy their houses for lower costs. Now they’re worth more because they’ve fixed them up . . . The business people and older people like myself work with the younger ones who come here for the quality of life . . . We did the [public art] pigs and the rocking chairs. This year we’re painting boxes — 20-by-20-inch boxes painted by artists — called “Brandon Thinking Out of the Box” . . . There’s a wonderful sense of community — people in this town feel good about themselves.

SD: You also are on the board of the Vermont Arts Council, and I believe last year’s “Palettes of Vermont” project was your idea?

WK: Yes.

SD: You have a painting of the Round Barn now hanging in the Round Barn. Did you paint that specifically for this show, or is that an older piece?

WK: I think I did that in

1993 . . . I’ve also painted the Ticonderoga, the lighthouse . . . I’ve been influenced by some of the houses, too.

SD: It must be a favorite at the Shelburne Museum gift shop.

WK: Oh, boy, do they have stuff there! . . . I’m pleased that the museum makes revenue by selling those things. That’s great . . . The museum doesn’t run on air. This is probably one of the best in the whole country. It’s our museum — it belongs to Vermont. We have to go to it, take people to it.

SD: Warren, you’re still a cheerleader.

WK: I know. But it’s true.

SD: One last question: What achievement are you proudest of in your life so far?

WK: Well, I think I’m very fortunate that I have family, community, friends; I’ve accomplished something . . . I remember a student at Castleton once, we were discussing drugs, and I said I’d never tried them. He said, “Mr. Kimble, you’re high on life.”

Info:

"Warren Kimble's America," Shelburne Museum, May 18 to October 26. Reception for museum members and guests May 15, 5:30-7:30 p.m.

For other exhibits and events this season, visit www.shelburnemuseum.org.

More By This Author

Speaking of...

-

Totally Transfixed: A Rare Eclipse on a Bluebird Day Dazzled Crowds in Northern Vermont

Apr 10, 2024 -

Q&A: Catching Up With the Champlain Valley Quilt Guild

Apr 10, 2024 -

Video: The Champlain Valley Quilt Guild Prepares for Its Biennial Quilt Show

Apr 4, 2024 -

Approaching Three Decades, Shelburne’s Dutch Mill Diner Gets a Refresh

Mar 12, 2024 -

Electra's Restaurant in Shelburne Has Something for Everyone

Mar 5, 2024 - More »

Comments (2)

Showing 1-2 of 2

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.