Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

-

Education

Scott Official Pushes Back on Former State…

-

News

Burlington Budget Deficit Balloons to $13.1 Million

-

Education

Senate Committee Votes 3-2 to Recommend Saunders…

- Court Rejects Roxbury's Request to Block School Budget Vote Education 0

- Norwich University Names New President Education 0

- Media Note: Mitch Wertlieb Named Host of 'Vermont This Week' Health Care 0

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

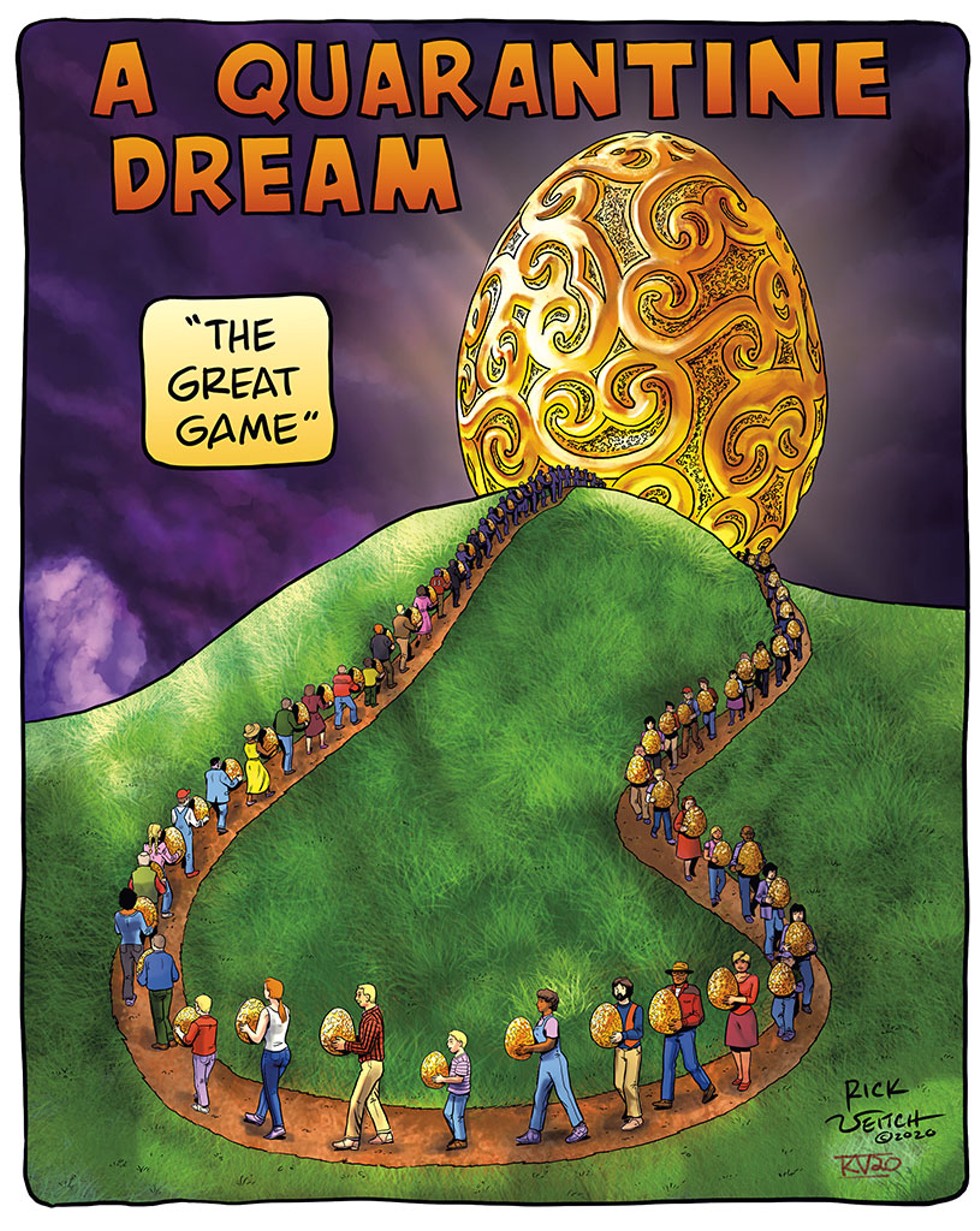

Green Mountain Quaranzine: Seven Days' First (and We Hope Last) Pandemic Literary Journal

Published May 6, 2020 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated December 21, 2021 at 8:13 p.m.

There's this guy I follow on Twitter. I'm not sure when or why I followed him or even who he is, really. I gather he's some kind of famous because he has that little blue check by his name. Other than that, I know only that he lives in an apartment building in a Big City, which for our purposes is probably all that's important.

Anyway, when the world changed and our age of isolation began, blue-check guy started tweeting about his neighbor. Every morning, the neighbor would let his young son out on the balcony to scream at the top of his lungs. And most mornings, there would be a tweet about it. But the almost-daily, sub-280-character updates weren't of the tweet-rage variety you might expect. Instead, they expressed an awed sort of admiration — for the dad who let his son go yell at the world, but mostly for the kid himself. Then one day, after several weeks had gone by, the dad went out to scream, too.

Contributors

Whenever this all ends — meaning the pandemic, not the world — I have a feeling that will be one of the lasting images burned into my mind, even though I never actually saw it and don't know the people involved: a father and son, screaming together into the void, because it's all they could do.

There are billions of illustrative little stories like that one happening all the time, all over the planet, while we experience this defining period of global history — as that brand-new cliché goes — together apart. Over the past several weeks, Seven Days has endeavored to tell some of the most compelling and important tales from our small corner of the world. But certain kinds of stories — like, say, that of our friends on the balcony — require a slightly different touch, or a different perspective, from what journalism typically allows.

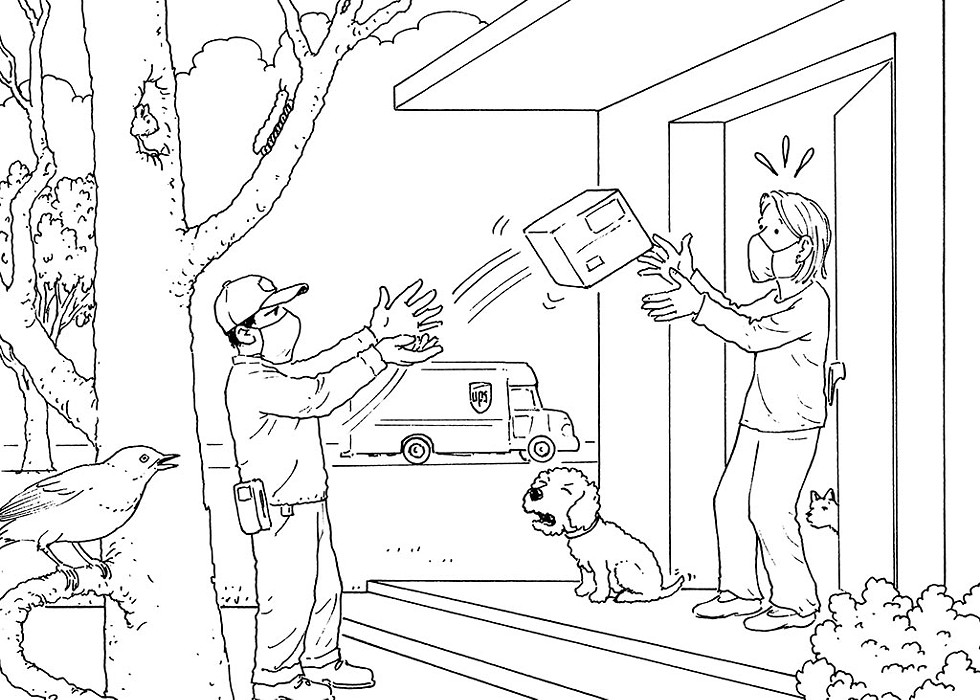

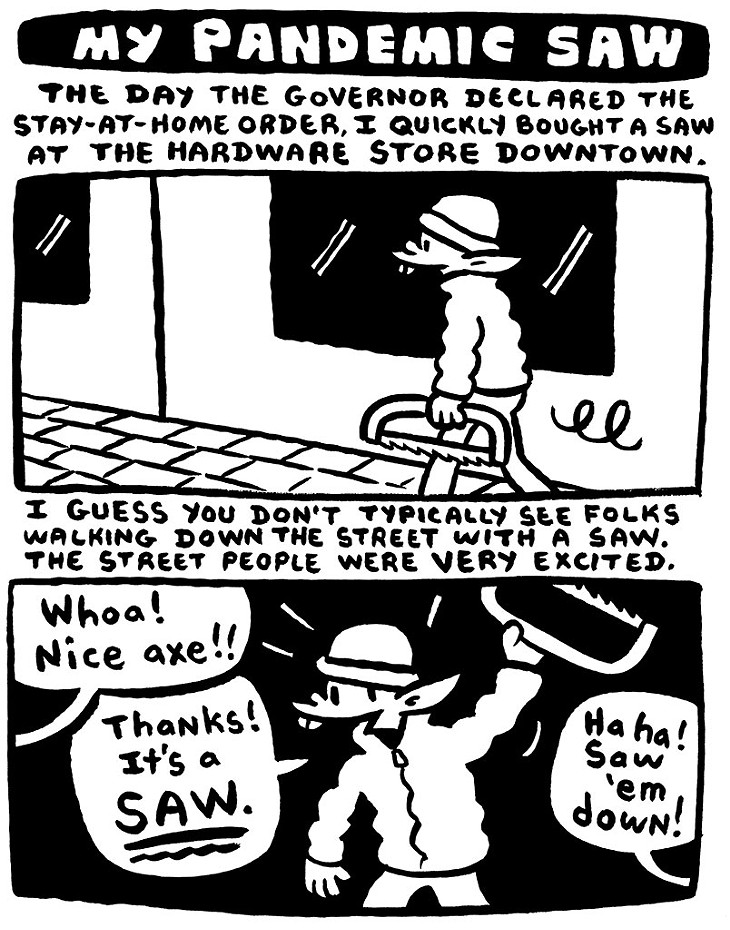

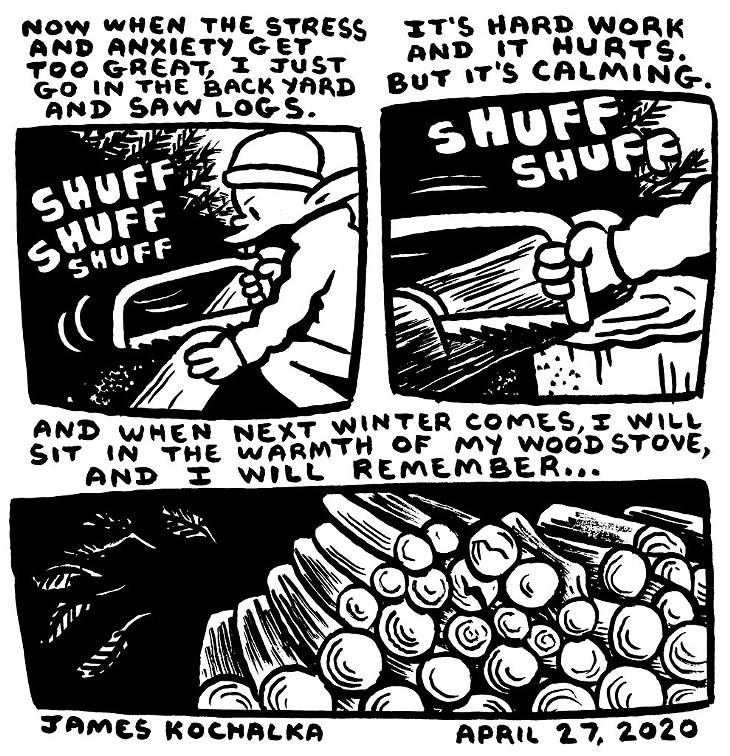

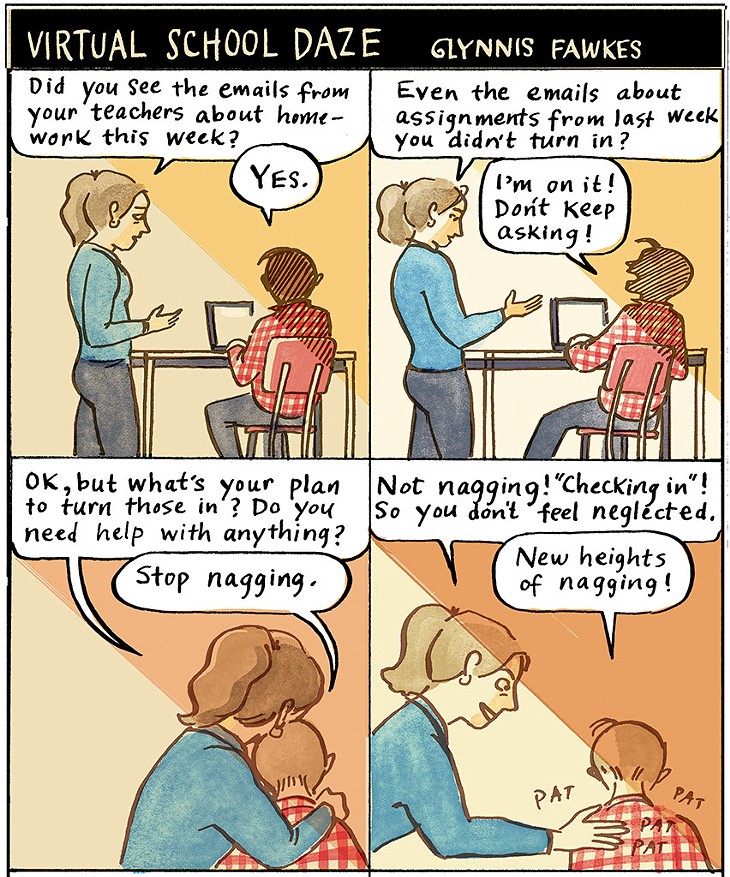

So for this week's edition, we called on a variety of Vermont storytellers — authors, poets and cartoonists — to reflect on how life has changed in the past seven weeks and What It All Means ... or maybe doesn't. On the following pages you'll find essays born of long drives in the country and short walks in the rain, of settling up with the Devil and with a kind, bourbon-sipping neighbor. There are cartoons on the trials of homeschooling and the therapeutic qualities of sawing wood. There's a poem about hot sauce.

Color the Cover Contest!

Looking for a creative outlet? You’re in luck! This week’s cover is a coloring page drawn by cartoonist Harry Bliss, and we want you to bring it to life. While you’re sitting around the house this week, grab your crayons, brushes and glitter, and dazzle us with your creations!

How to Enter

- Post your creation to Instagram and tag @sevendaysvt! If you aren’t on Instagram, submit your photo here.

- Submit your entry by Wednesday, May 13, at 5 p.m. to be eligible.

- Check our Facebook page on Friday, May 15, to see our top five favorites and to vote for yours!

In these true tales and several others, you may find some solace, or an observation that rings true, or a good laugh, or a poetic line that inspires reflections of your own. Or maybe you'll just find a brief escape in some well-wrought words by talented local storytellers.

Regardless, you can always step outside for a good scream.

— Dan Bolles

James Kochalka was the first cartoonist laureate of Vermont. In 2019 his book Johnny Boo and the Ice Cream Computer won an Eisner Award.

Happy Birthday

When our friend G. turned 8 the other day, her parents whisked her off to Montréal for a celebratory breakfast. They had farm-fresh eggs collected that morning, brioche French toast and chocolat chaud, as Québécois folk songs played in the background. At lunchtime they sped off to New York City for ballpark franks and maple ice cream made with Vermont Grade A syrup from trees tapped just a few weeks before. Dinner, G. thought, might be in Paris — it was going to be a surprise, but she was pretty sure there would be pomme frites and a triple-layer gateau for dessert.

G. told me this as she sat on the hood of her parents' car, which was parked off to the side of the gated road between her house and mine. She was 20 feet or so away — far enough to keep us all safe, but not so far that I couldn't admire her fancy new ankle-strap shoes, gauzy princess dress and tiara bedecked with forsythia.

Earlier in the day, I watched my daughter "shop" for G.'s birthday presents on her bookshelves, pulling down volumes she had loved when she was 8, and gathering the stuffed animals G. liked to play with when she visited, back when neighbors casually stopped by each other's homes. My husband made a card and I dropped everything into a shiny pink bag left over from Christmas and tied it with a ribbon. We put the bag on G.'s side of the gate, then retreated when her mother retrieved it, even though they had been self-quarantined for nearly a month, and so had we.

The gate was a physical reminder that, for the time being, we are all a danger to each other. But birthdays are also a reminder that, even in the midst of a pandemic, we need to take time to celebrate life itself. This one may not have been ideal: It was one of those chilly April days when snow fell in the morning, the dogs had to stay home because they are constitutionally opposed to social distancing, and we had to outshout the wind. But it was merry and carried along by flights of fancy. (Though, to be honest, my first question, when G. told me she'd been to Montréal that morning, was to ask how her parents were able to convince the border guards to let them cross into Canada.)

And it was refreshing to engage with each other without a screen in between and the inevitable lag that comes from our insanely slow and inadequate rural internet. (Don't get me started. Or maybe do. The internet here in Ripton doesn't even achieve what the Federal Communications Commission considers minimally acceptable, and no number of calls to Consolidated Communications seems likely to change that.)

Less than 24 hours later, though, there we were on Zoom, one small tile in the mosaic of our friend Lisa's family and friends, who were gathering to toast her on her 65th. There was red wine, white wine, craft beer, hard cider, herbal tea and seltzer, lifted up in her honor from all corners of the country. As more people logged on, we were each reduced in size, till we were postage stamps on a virtual birthday card.

It wasn't long before talk turned to the pandemic — how could it not? Lisa and her husband, David, are both physicians in New York City. A few weeks before, David, a nephrologist, told me that one thing that hadn't received much coverage in the press was that COVID-19 attacked the kidneys. He was expecting dialysis units like the one he ran to become the new front line. And there he was, on this very day, quoted on the front page of the New York Times because the future he'd predicted had arrived.

Questions ping-ponged back and forth to him and to Lisa, an infectious disease doctor, who serves as the epidemiologist for a consortium of medical centers around the city. "My phone never stops ringing all day long," she said, which was both an explanation and code for us to change the subject.

Someone held their dog to camera, then everyone did, and for a few minutes the dogs took over the party. Then there was more chitchat — talk about meals we had made, books we were reading, Zoom cocktail parties and Zoom game nights. At some point, someone starting singing "Happy Birthday" and everyone joined in. We were so well practiced from washing our hands that we almost sang it twice.

Sue Halpern is the author of seven books, most recently the novel Summer Hours at the Robbers Library. She lives in Ripton.

Willow Talk

I have been taking pictures of my neighbor's tree for the past seven weeks. I don't remember why I started, but now, whenever I venture outside to walk the dog or fetch yesterday's mail (yes, we let it "air out" in the mailbox for 24 hours — don't you?), I stop in the middle of our dead-end street to look up at the willow weeping high above the cedar hedge.

And then I take its picture.

Laptop cameras aren't kind to me. I look like a retired boxer in Zoom meetings. A client recently asked if I was tired.

"I guess we're all tired," he said. "This whole thing's like prison. Maybe worse."

I thought about not saying it but couldn't help myself. Everything's different now. I leaned in so the camera accentuated my swollen eyes and cauliflower ears.

"No, it's not," I told him. "I've been to prison. Trust me, this isn't anything like it."

I took the dog for a walk in the rain last week. It wasn't something either of us wanted to do — it just needed to be done.

I stopped at the tree and looked up, cold water pouring off me in steady streams. The willow's tendrils whipped about. I raised my arms, Shawshank-style, and tried imagining those long, thin leaves draped over my hands, my elbows. The cauldron sky roiled high above the earth. I wanted to think about redemption, about what comes next, but the dog yelped and tugged at his leash, reminding me that there were more pressing matters to tend to.

The day before Governor Scott reminded Vermonters to leash their dogs at all times as an added precaution, two unleashed dogs ran up to me on Mount Philo just after sunrise. I raised my hands and stepped far off the road, into the woods.

"You're fine with them, right?" the dogs' owner smiled.

I shook my head. "No, not really. They should really be on a leash."

She pointed at her earbuds. "Sorry, I can't hear you."

I thought about not pursuing it but couldn't help myself. Everything's different now. I pointed at her dogs and yelled, "They should be on a leash!"

Her smile crumpled into a scowl. "YOU should be on a leash!"

The man in the choke chain collar waiting in line outside of Trader Joe's began vaping through his black bandana mask. Giant clouds like floating sheep. My initial shock was quickly replaced by a deep admiration for his strict adherence to mask protocol. If only the rest of us had a fraction of his dedication. This vaping man may've set the pandemic gold standard, a true hero for our time — maybe not the hero we wanted, but certainly the one we deserve.

There are other photogenic tableaux in my neighborhood that are probably more deserving — the budding maples and blooming magnolias, the goldfinches pecking at red bird feeders — but it's the willow I keep returning to. I don't know why. I read that in its native China, the weeping willow is a symbol for immortality and rebirth. Maybe I should pretend that's the reason and just be done with it already.

A high school friend insists on calling it "the China Flu" on Facebook. Suffice to say, we don't see eye-to-eye on many things. I thought about arguing with him like I usually do but couldn't help myself. Everything's different now. I closed my laptop and went for a walk.

Its leaves are longer and more golden than they were when this all started. Normally I wouldn't have noticed this, but this year is far from normal. Maybe I've been standing beneath a weeping willow for seven weeks just to see it change. As it turns out, it became something else without ever having left its home.

Kind of like us.

Eric Olsen makes websites and music and feels pretty lucky just to be here.

Breathe

After another day in isolation,

a day where family and community

shrink smaller in practice,

the little girl startles in

the middle of this March night

calling, Papa, and when I arrive,

she whines, My lips

hurt. Moments later, My tummy

hurts. She demands I sleep

beside her, hands weaved together

like the smallest nucleus as

she struggles to decline

into sleep, which takes over

an hour, and as she finally fades,

her mind no longer kneading

over COVID, corona, isolation,

and self-distancing, all concepts

her mama and I try to whisper

about but words now of little girl's

tongue, her breathing becomes

a ghost of a wisp, shallow and

beautiful and as I listen to

the music of it, I cannot help but

nightmare-imagine to another state

so many stay-in-place orders

away to my brother's bedroom

where I must imagine—since

we cannot actually visit for fear

of all this crowned sickness—

to the few words he uttered

yesterday morning when I called

after hearing the news, he rasped,

It's so hard to breathe.

Sean Prentiss is the author of Crosscut: Poems and Finding Abbey. He and his family live on a lake in northern Vermont.

What If This Means Nothing at All?

What if we're not better after all this? What if we haven't learned a damn thing? If your real and virtual social networks are filled with people of privilege, this is the undercurrent. You might start to believe the reason for a global pandemic is to make every single Alison Roman recipe, reach the end of Netflix, bake all the bread, take up beekeeping, get ripped.

When the announcement came that schools were closing — as Jon, my future ex-husband, with whom I still live, temporarily lost his job — we retreated into our corners, we ran on adrenaline from the novelty of fear and disruption. Let's batten down the hatches. But also: Let's learn something. Let's attempt to comprehend an actual existential threat. But also: Let's come out of this better than we were before.

It did not start well. On the same day I wrote an article for the Cut about how to work from home with kids, I yelled at my actual kids as they argued with each other, "LIKE I'M IN THE MOOD FOR THIS SHIT." Later that same day I announced to my family, but mostly to myself, "Don't judge how other people cope." Watch your shows, keep your bees, get those abs of steel, honey.

Throughout the day, on whatever day it is now, I watch others' wheels come off on Instagram. I'm sucked into the darkest dens of pandemic humor on Twitter. I'm assaulted on Facebook by senior photos from the 1980s, as if any current high school senior gives a damn what reflections you might have on your own ancient prom.

All the while, we're changing the topic. We know what we fear most is death. We worry it will come without being able to hold a hand, touch the hair, say, "I love you. I forgive you. I will be OK, we will be OK." We fear we will have to say or hear it through a screen, a dystopian nightmare.

And if we actually avoid death this time, what if this whole experience didn't mean anything? What if we come out of the pandemic the same flawed, fucked-up people who went in? What if we aren't better? What if we're actually worse?

What if we remain traumatized by the sight of bare hands, the thought of sweaty people jammed into a club shoulder-to-shoulder, the entire concept of sticking your tongue in someone else's mouth? What if we lose the shirts off our backs? What if we lose our last scrap of hope? What if, for those of privilege, we begin to grasp that death, trauma and financial ruin can happen for no good reason at all? What if those bootstraps you kept telling others to pull up break off in your own hands?

I have found myself wrapped up in surprisingly casual conversations with my two teenagers about death, about the point of life. They have brought this up on their own. We've lingered way past my bedtime, my self-cut hair looking like it was styled by a typhoon. And I tell them, in that way parents do, Ah yes, this is actually a Big Question. A lifelong question.

I tell them that they're only at the beginning of asking questions like this and may never be satisfied with the answers. And I tell them that, as I get older, the only point I can figure out is the day right in front of me. Even then it's only minute-by-minute, putting one foot in front of the other.

When Jon and I were dating and I'd spin out about the unknowable future, he'd respond, "One day at a time." It was a mantra his mother, Janie, had adopted as she persevered through ovarian cancer. But I wanted actual answers. And his actual answer grated on me to the point that, if I saw it coming, I'd cut him off with "I swear to God, don't 'one day at a time' me right now."

Now, decades later, I have finally come around. Look at all these ghosts we have on our calendars. Look at the shadow lives we would be leading if not for this. Look at everything we would be complaining about, that now we're desperate for what it represents. Boring and predictable has never sounded so good. It's a hell of a thing to feel wistful about a dodged pelvic exam.

What is the future, anyway, other than specific wishes pinned on a grid that owes you nothing?

Last weekend I was so furious with my family and my circumstances that I walked out of my house and said only, "I'm leaving." I've had to drive to get away. The walks I used to take to clear my head now often leave me more stressed and angry. Bike paths are too crowded and I fear every runner that puffs past me, every little kid on a bike who swerves within a foot of me, every dog still off its leash as the owner shouts, "He's friendly!" Bitch, I never cared how friendly your dog was before all this and I especially don't care now.

I grew up loving cars and I loved the thinking that I did inside them. First as a kid, with my forehead pressed against the window, watching the landscape timelapse past me. Wondering about life. Then, as a teenager, chewing up country roads, pulling over to smoke a cigarette and stare at the stars.

Now, my car is a spaceship that I launch into the countryside. I get in and floor it in one direction until I'm calm. I think of all the places I wish I could stop along the way — the destination used to be the point. But now I just drive somewhere and back, keeping my contagion contained. One weekend I drove from Burlington to Vergennes and back, playing Radiohead so loud I gave myself a headache. Last weekend, with the power of fury behind me, I made it almost to Rutland before I calmed down.

My dog was with me, so I stopped to let her out at a cemetery before we turned around and headed home for another week in lockdown. Cemeteries have become the only places I can collect my thoughts, the only places powerful enough to snap me out of my pity-party bullshit. The sun was shining and this cemetery was empty, save the souls I could not see. Wind chimes on graves caused me to whip around, looking for loose dogs.

I came across the weathered grave of a 2-day-old baby who lived and died in 1950. That was a different time, I thought. As if death was solvable now. As if the reason I was in a cemetery an hour and a half away from home wasn't evidence to the contrary. I came across more modern, smooth tombstones — for a girl only 7, a teenager born the same year as me, several 20-year-olds lost to different wars. What was the point of any of it? What if the dead can't hear wind chimes?

Who are all these Instagram posts for, these Twitter jokes, these bees and loaves and quads? We are launching ourselves into space any way we can right now. We are sending transmissions to anyone who will listen. Can you hear me? Do you see me? Do I matter? Am I good? Will you remember me when I'm gone?

We made our way back toward my car, where I had pulled off the narrow, potholed road and onto grass stubborn enough to still believe in spring. A looming statue of Jesus with outstretched arms looked down on us. My dog growled and ran away from it, barking. She thought he was coming for us.

Kimberly Harrington is the author of Amateur Hour: Motherhood in Essays and Swear Words and the forthcoming But You Seemed So Happy. Her work has also appeared in the New York Times, the Cut, the New Yorker and McSweeney's.

Crossing Buels Gore

Driving past

houses at twilight,

the lights of others

are easier to see,

islands of being,

glimpsed & longed for

through bare branches,

an alpine glow of sorts,

the hundreds of

ski chalet exiles,

who now,

for the life of them,

are just happy for space

& to cling to the shelter

of cliffs.

Their trails are empty,

smatterings of snow

unlock the deep mountain

ravines, oxygenated water

pummels the isolated creeks

to their peak,

over-spilling a red-hued

forest and way lower,

the farm runnels.

It's all around us,

the cure, aiming

like sap for the tank

yet uncollected,

planted by God, like trees

but six feet apart

- did I say my heart

is a wreck,

wandering from

here, to who

knows where

next?

Kristina Stykos is a record producer and writer who also runs a professional gardening business, Gardenessa. Her album River of Light ranked second on County Tracks' "Best Vermont Albums of 2019" list. Her recently published book of poetry and photographs, Ridgerunner, is now available in two editions from Shires Press.

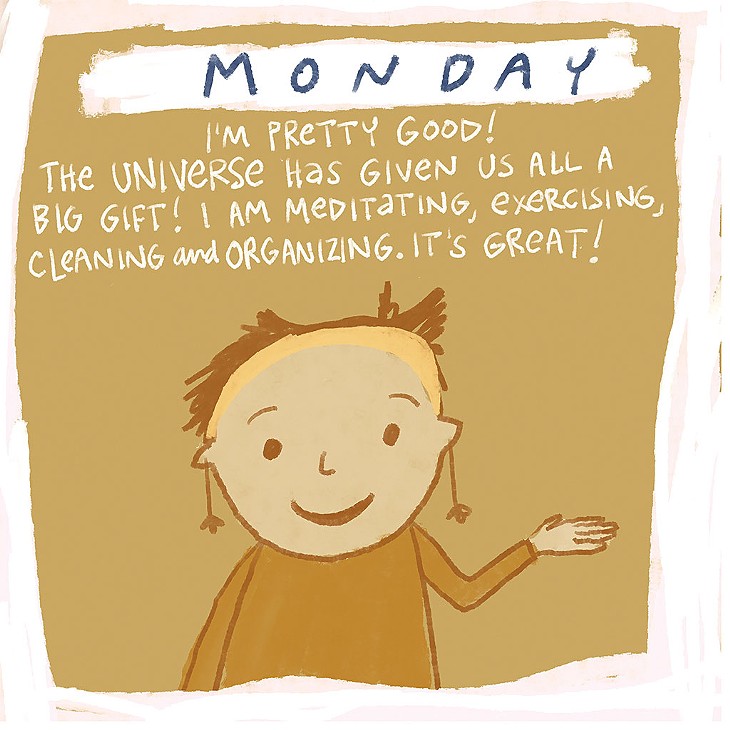

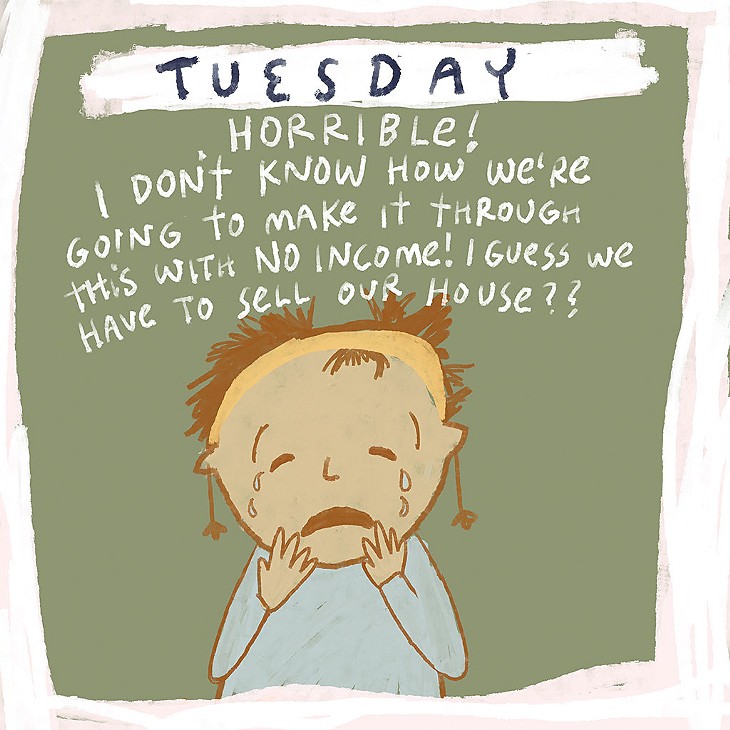

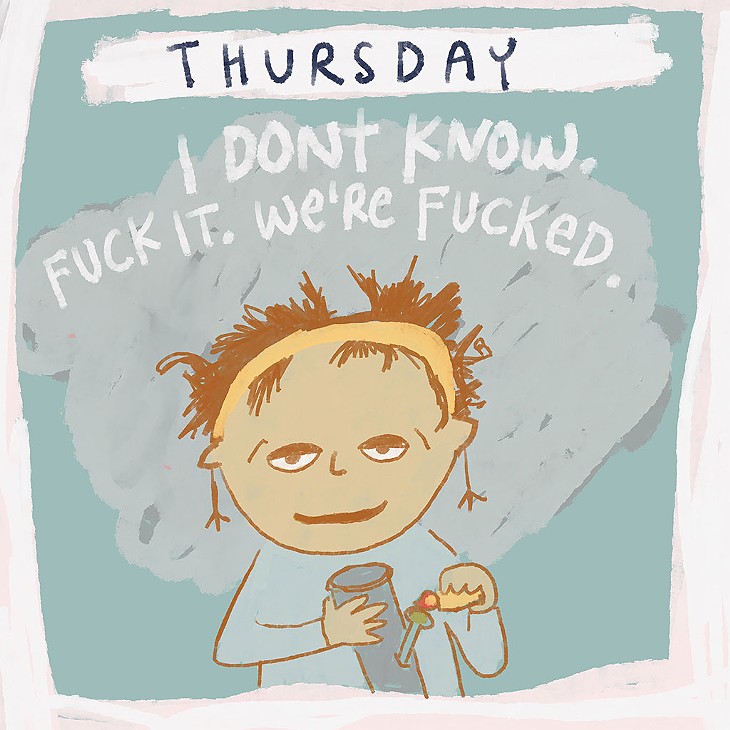

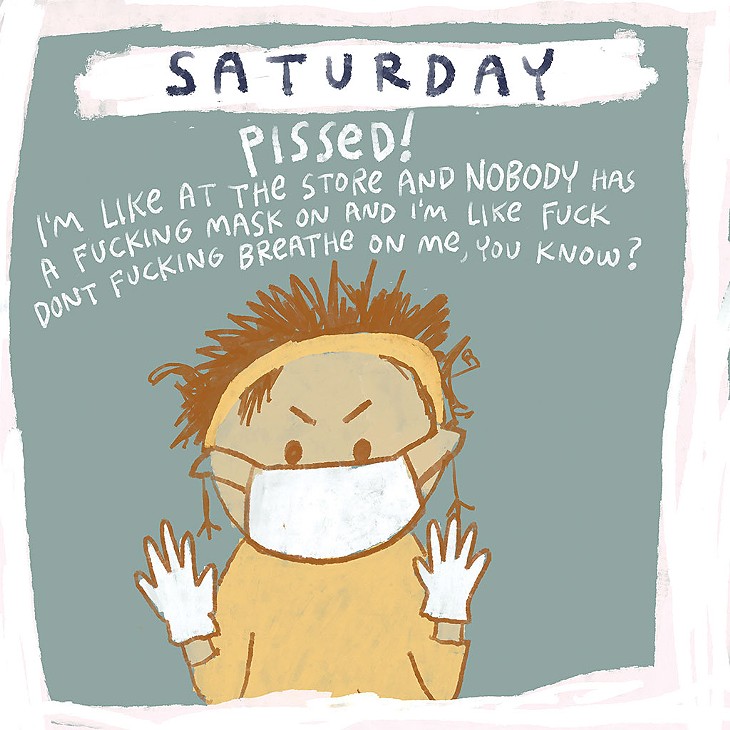

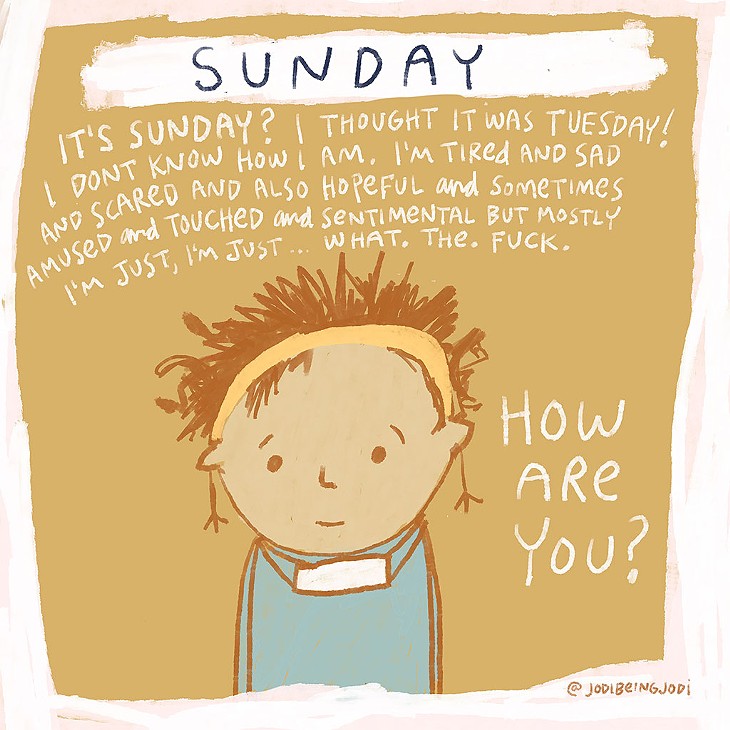

Jodi Whalen is an artist and illustrator in Burlington. Her style is quirky and boundless, and her artwork includes cartoons, inspirational illustrations and bread lamps for August First, the bakery-café she owns with her husband.

Not the Quintessential COVID-19 Poem

When the whole COVID-19 isolation thing started, I thought I'd be writing a bunch of emotional, heartfelt poems about what it meant to be physically cut off from the rest of the world. About what it meant to have so much time with two of the people (my wife and daughter) I love the most. About the challenges that isolation from most of the world and increased contact with my immediate family would bring. We make art from our challenges and scars, right?

I'm about to make myself sound like a real jerk here. And I guess I deserve it. When I was in college, I was in a creative writing class with a girlfriend. I just loved the heck out of this girl. So one time when we met up she said that her apartment had just been broken into. I can't believe I'm repeating this, but my first response was ... "That's great material for a poem!"

She broke into tears, and I mentally slapped myself for thinking about creative content instead of just giving the girl a hug. In the next 15 seconds, I gave the girl a hug. I think about that a lot, and it was 23 years ago.

Months later, she would write about the break-in. But at the moment, it was too soon.

So those emotional, heartfelt poems that I expected to write in the wake of COVID-19, well, they haven't happened yet. It might be too soon for me. But it's OK to not be writing the quintessential COVID-19 poem right now. It's OK to not have an immediate response.

In the meantime, there's hot sauce.

I love hot sauce. I have hundreds of bottles of hot sauce. And my response to COVID-19 has been to write about something that is completely un-COVID-19-ish. Some people escape into episodes of "Tiger King" or reruns of "Seinfeld." It turns out that I write about hot sauce. I'm sure that, given time, a deeper response to the pandemic will come. But right now, this is what I have: dozens of poems (if you can call them that at this point) about hot sauce.

Maybe it's a dispassionate response, even a form of escapism. But I just have to throw myself into something, and for now this is it.

Chile

The word hails

from Nahuatl, the Aztec

language that gave us

chocolate, avocado,

tomato, peyote.

During spiritual fasting,

the Aztecs abstained

from chilis & sex,

& only conjecture

can tell us

which was harder

to renounce. Tell me

it's the one that has

to do with your tongue,

& that's the most

nebulous hint

in the history

of hints. Chile:

the least chilly

bite ever to turn

the back of your

throat, lips, rim

of tongue, to the most

glorious tinder.

Blink, & you see

sequins, & then the love

scene turns

into a heist.

Stephen Cramer's most recent book of poetry is Bone Music. His anthology Turn It Up! Music in Poetry From Jazz to Hip-Hop was just released.

Damn Nationals

This is all my fault, folks.

On October 30, 2019, with the Washington Nationals trailing by a run in Game 7 of the World Series, I made a deal with the Prince of Darkness. He would allow my beloved Nats to win in dramatic fashion. But in return, Washington would never win against my mortal enemies, the New York Mets, in 2020.

Small price to pay, I thought, as I signed with a quill pen dipped in someone or something's blood. Two minutes later Howie Kendrick clanged a two-run dong off the right field foul pole to put the Nats up for good. I was extremely happy.

The next morning, I started humbly intimating to friends and family that the team had won because of my arrangement with Satan. I was expecting a few attaboys, some backslaps and thumbs-up emojis. Instead I received a torrent of wailing and existential fear, which is a lot to bear when you're "day after a Game 7 World Series win"-level hung over.

A friend patiently explained that this Lucifer guy is known for introducing unexpected ironic consequences into his business deals. This was news to me. The friend turned hostile, berating me, saying that every single depiction of the Devil in popular culture involves this trope. "Oh, yeah. That rings a bell," I lied — because I didn't want to look like an idiot.

And now here we are. The Nats will never beat the Mets this season because, due to the coronavirus, there likely is no season. Frankly, enforcing the letter of our agreement by unleashing a global pandemic seems like a bit of a desperate flex on the part of Old Scratch. Maybe a touch of overcompensation? I did a little more digging into this pop-culture Devil stuff, and you know what he's never depicted with? Large, visible genitals. Just something to think about.

Regardless of Beelzebub's wang size, I'm not happy about the situation. Having no baseball is bad. Having no baseball because of a devastating virus is much worse, because it gives sports haters a license to Put Things in Perspective. "Really puts things in perspective," they say, as if they are blessing one of Plato's cave dwellers with wisdom from on high instead of quoting a cliché on the level of "Live, Laugh, Love" Etsy décor.

It would be easy to dismiss these people as nerds, but that isn't fair: Many of them are actually dweebs. Plus, I have perspective. After all, I didn't sell my soul to the devil. That would be ridiculous. It was just a game. My soul would have been worth at least two World Series wins.

Hoping to atone for my role in all this, I decided to give back. On March 26, what would have been Major League Baseball's opening day, I broadcast an RBI Baseball simulation of the 1987 MLB All-Star Game to a few hundred viewers on Twitch. I even convinced a reporter for the Washington Post to cover it. Sports reporters are desperate for content right now. I think I could get one to come watch me do my laundry if I tricked them into thinking I was a severely malnourished Mike Trout.

I assumed my improv comedy experience would prepare me for announcing a game and I was right: Years of doing bad improv made it much easier to do bad commentary. The Post reporter described my performance as "Boom Goes the Dynamite without the natural charisma."

Increasingly desperate for a baseball fix, I consulted the Minor League Baseball schedule. If the virus subsided by July, would the Vermont Lake Monsters be able to take the field? But sadly, due to MLB's rumored contraction of the minor league system, Champ's favorite team may have played its last short season.

The silver lining is that, by ceasing to exist, the quality of the product would only dip slightly. Centennial Field was last renovated shortly after the Mighty Casey struck out. And Lake Monsters games were never slick affairs.

One of the Lake Monsters' between-inning entertainment activities consists of two kids throwing plastic bottles into a recycling bin. The winning child receives a free hot dog, and the losing recycling bin gets banged by a Houston Astros prospect. I always thought it was dumb, but that was before the sports drought. Now that I have three hours a day to fill where I used to be watching baseball, I tried to find some parents who would let me pay to watch their children toss garbage around. I was banned from Front Porch Forum almost immediately.

So what's next? Tracking down bootleg streams of Taiwanese minor league games? Rewatching my World Series documentary DVD a 30th time? Throwing water bottles into the trash myself? The past few weeks actually have Put Things in Perspective, and that perspective is this: Global pandemics suck big time. If you know any goat-legged fellows who can do something about this situation, I've still got a soul to offer.

Conor Lastowka grew up in the Washington, D.C., area. He works as a senior writer/producer at RiffTrax. His novel The Pole Vault Championship of the Entire Universe is available at audible.com.

Rick Veitch was born in Bellows Falls and began drawing comics at an early age. He is cofounder of Eureka Comics, specializing in educational and informational graphic novels. In April, he was named the fourth Vermont cartoonist laureate. He lives in West Townshend with his wife, Cindy.

Kirby Veitch graduated from the New Hampshire Institute of Art. He is a fantasy artist and comic book colorist whose clients include IDW Publishing, the International Monetary Fund and McGraw Hill Education. He lives in Brattleboro.

Good Bourbon Makes Good Neighbors

On the third anniversary of her husband's death, I asked Joan how she'd been feeling. My next-door neighbor for many years, she was well into her eighties then, but plenty spry. She told me she missed him. The house was quiet without his booming voice (he'd been a bit deaf in the later years). She said sometimes she got terribly thirsty.

"That's not good," I said. "You have to stay hydrated. I could loan you some of my bicycle bottles, they're impossible to spill. You could have one by your bed, one by your chair."

"No," she answered, "I mean bourbon thirsty."

"Well, I'm a beer and wine and rum guy," I said. "I don't know anything about bourbon."

"I was a teacher for many years," Joan replied. "I can teach you."

And so our friendship entered a new phase. She'd make us a casserole dinner, I'd fill glasses with ice and bourbon, and while she savored her drink with reverentially closed eyes and I choked mine down sip by sip, we would sit and ridicule the president and have a high old time.

Then the virus came. Now 89 and some months, Joan is no fool, no weakling, and not one to become dependent. But she knows she's in danger, if she ventures out into the world. So, for once, she allowed me to do things for her.

Mainly it was groceries, her requests so modest it embarrassed me — a flat of water bottles, a package of paper towels. She'd call to say thanks, but her real purpose was to find out how much I had spent, because she was determined to settle up with me. In her view — implied but never spoken — fetching things from the store was kindness on my part, but actually paying for them would be charity, and Joan wanted none of that.

One day, she went all out and asked me to pick up some coffee. Also, laundry detergent pods. Both of my grown sons are home from New York City for the duration, so my grocery receipt totaled in the hundreds. But on her thank-you call she insisted I calculate how much her goods had cost.

What is it to be alive, when our normally free existence and community are reduced to solitude in our homes? Is an insistence on being ourselves, our actual, stubborn selves at all times, perhaps a sign of strength and determination to survive? Is that how we make it to 89, still appreciating a stiff bourbon on the rocks?

A few days later, I was out in another neighbor's field and spotted a car in my driveway. I hurried home, but the car was gone before I arrived. However, in my garage there was a container of fresh cookies. And taped to it, a check from Joan for $37.

Stephen Kiernan is a Vermont novelist and journalist with more than 4 million words in print. His new novel, Universe of Two, comes out August 4.

Glynnis Fawkes published Charlotte Brontë Before Jane Eyre and Persephone’s Garden in 2019. Her work has appeared in the Vermont Quarterly, Seven Days and the New Yorker website. She teaches at CCS and lives in Burlington with her family.

In Our Wake

Inside these hands

A golden chance

Within these walls

A castle falls

While all the peasants dance

Where does one turn

In a house of mirrors

If everywhere you look there you are

If silence becomes too loud to hear over the birds'

Songs

When touch seems

a distant stranger

fuzzy and still wet with hazy memory

No one said anything about the masks we'd wear

over the masks we wore

Before

And yet the sun still shines through gloom

And flowers dare to bloom

I saw a patch of onion

A robin thrusting its chest out

Eyed me suspiciously

As if to say

What are you doing here

It appears we are still here

Maybe we can outlive

and outgrow our shadows

Maybe life will look us square in the eyeball

And not notice our flinching

Imperceptibly

Or see it and still forgive us our immortal mortalities

Maybe today will be the day the walls part like seas and the ceilings raise

and the light

has its way with us

Maybe the rain will merge with the sweat born

of our contained lives

and become indistinguishable

Maybe we'll take ourselves out of ourselves

cast away

the plastic packaging

And see something

more alive

Something more fun

to play with

Than fear

and Shallow mirrors

Maybe we can be friendly to ourselves

even when the world

is not watching

When the ceaseless eye

of Babylon has gone

to sleep

or long died

We can be here

Creating musing

Imagining

Envisioning

Life as it could and can be and leave what it was and is

In our wake

Spoken-word poet, MC and teaching artist Rajnii Eddins has been engaging diverse community audiences for more than 27 years. His latest work, Their Names Are Mine, confronts white supremacy while emphasizing the need to affirm our common humanity.

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

About The Author

Dan Bolles

Bio:

Dan Bolles is Seven Days' assistant arts editor and also edits What's Good, the annual city guide to Burlington. He has received numerous state, regional and national awards for his coverage of the arts, music, sports and culture. He loves dogs, dark beer and the Boston Red Sox.

Dan Bolles is Seven Days' assistant arts editor and also edits What's Good, the annual city guide to Burlington. He has received numerous state, regional and national awards for his coverage of the arts, music, sports and culture. He loves dogs, dark beer and the Boston Red Sox.

More By This Author

Latest in Culture

Speaking of...

-

In 'The Glass Château,' Stephen Kiernan Crafts a Tale of National and Personal Renewal in Postwar France

Dec 20, 2023 -

Non-Fiction Comics Festival Illustrates Graphic Novels’ Versatility

Nov 15, 2023 -

On the Beat: The Return of Bauschaus VT and New Music From James Kochalka Superstar

Nov 1, 2023 -

Waitsfield Cartoon Show Features Comic Relief and Revelations

Sep 13, 2023 -

Where Art Thou? Head Inside the Studio to See Artists at Work

Sep 5, 2023 - More »

find, follow, fan us: