Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

-

Education

Scott Official Pushes Back on Former State…

-

News

Burlington Budget Deficit Balloons to $13.1 Million

-

Education

Senate Committee Votes 3-2 to Recommend Saunders…

- Court Rejects Roxbury's Request to Block School Budget Vote Education 0

- Norwich University Names New President Education 0

- Media Note: Mitch Wertlieb Named Host of 'Vermont This Week' Health Care 0

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

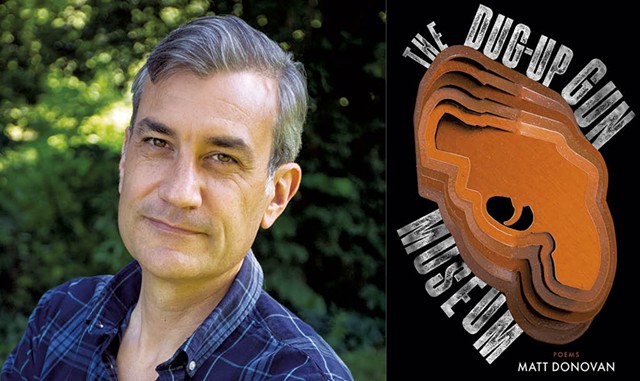

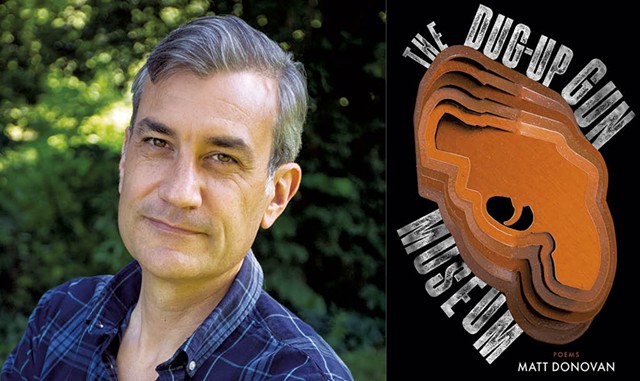

Matt Donovan’s 'The Dug-Up Gun Museum' Delves Into the American Obsession With Firearms

Published November 2, 2022 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated November 22, 2022 at 4:08 p.m.

click to enlarge

- Courtesy

- Matt Donovan | The Dug-Up Gun Museum by Matt Donovan, BOA Editions, 96 pages, $17.

When you hear the words "documentary" and "guns," a book of poetry might not be the first thing to spring to mind.

Smith College professor Matt Donovan will visit Norwich Bookstore on Friday, November 4, to read from his fourth collection of poems, The Dug-Up Gun Museum. In it, Donovan shows that poetry is an endlessly malleable form, capable not just of documentary but of anthropology, portraiture, witness, elegy and, above all, dialogue.

Faced with America's epidemic of gun violence, Donovan told me, he realized something: He didn't know much about guns or the people who own them. Rather than sit with the paralyzing grief of our now-daily mass shootings and police killings, he decided to hit the road, crisscrossing the country to investigate gun culture and talk about guns with people from all walks of life.

The heartrending, disturbing and blisteringly well-wrought poems that result take the reader to familiar places of grief, such as hospital emergency rooms and church support groups for survivors, as well as the unexpected. In search of understanding, Donovan witnesses and participates in some of America's most surreal pageantry, such as BB gun reenactments of the U.S. Navy's SEAL Team Six raid that killed Osama bin Laden and a carnivalesque version of the 1944 D-Day landing in a Pennsylvania field, where some participants cosplay as Harley Quinn and Gumby.

The book's title refers to a museum Donovan visited in Wyoming, but it also serves as a potent metaphor for a nation that can never quite bury its history of violence.

SEVEN DAYS: Tell me about the book's origins. And did you yourself grow up with guns?

MATT DONOVAN: The book grew out of deep concerns for the ongoing gun violence in America and our political polarization around this issue. It feels increasingly difficult to have real conversations around the topic of firearms, and I started to travel around the country in the hopes of initiating dialogue with people and trying to learn more. I didn't grow up with guns, and during my travels I always went out of my way to admit that. It was interesting how that admission helped initiate conversation.

SD: What were those conversations like? I'm curious, since the speaker of the poems is clearly horrified at everything they encounter. At the surreal D-Day reenactment, for example, it's hard to imagine a productive conversation about gun control! Have any of the people you spoke to read the book? If so, what were their reactions?

MD: As I started my travels, I learned that it's a mistake to think in a monolithic way about gun owners and gun culture. At that D-Day reenactment, there were no doubt participants there who would adamantly oppose any change to our current gun laws, but I also spoke to people who argued for commonsense gun law reform or who advocated for mandatory gun-safety classes before any firearm purchase.

Meanwhile, during a trip to Las Vegas, I spoke with the owner of a machine-gun shooting range who used the "driver's license" argument: that no one should purchase a weapon without proving they know how to safely operate one. I really welcomed those moments when my own assumptions and stereotypes were flung back at me.

In terms of your question about the book, though — no, I haven't yet heard from anyone who was quoted in the book.

SD: I love how you show some of the absurd ways guns can be fetishized — or even literally worshipped, as the shotgun-shell crucifix you find makes clear. This level of obsession seems to be a peculiarly American phenomenon; where do you think that comes from?

MD: That fetishizing of firearms was something that I encountered again and again, from the [National Rifle Association] National Firearms Museum (which offered, among many other things, guns engraved with topless women) to a shooting range gift shop [that sold] tank tops [on which] the phrase "Netflix and Chill" was replaced with the image of a pistol and "Netflix and Pew-Pew." I don't know if I can fully account for where this obsession comes from, but I'm deeply troubled by our inability to self-reflect upon our willingness to eroticize guns.

SD: That eroticization makes me think about how connected traditional masculinity is to guns. However, I chuckle imagining how the gun owners I know would react to being told they were eroticizing guns. Do you think the inability to self-reflect is connected to language? Do you think the liberal tendency to intellectualize and moralize our way to gun reform might be a doomed cause and might actually be widening the distance between opposite sides of the spectrum?

MD: That's such an interesting question, and again, I'm not sure that I have new answers. But in terms of our failures of language, I think folks on both sides of the issue risk falling back on the same reductive, predictable responses that are worse than nonstarters in that they're sure to foster mistrust and animosity.

Recently, I was interested to learn about the group 97Percent that was started by concerned gun owners who are seeking dialogue and common ground toward gun safety reform. To my mind, it sounds as if changing the conversation around guns is fundamental to their mission.

SD: I want to say that poetry can be a way of creating a bridge, but I'm not sure. So much of the poetry world is geared toward academia, for example. As a professor yourself, do you ever worry that poets are preaching to the choir?

MD: I agree that there can be a risk of the echo chamber when it comes to art and poetry, but then, in response to this, I often think of Garland Martin Taylor, an artist whom I met during my travels and whose sculpture "Conversation Piece" [a 400-pound steel revolver stamped with the names of Chicago children killed by gun violence] is featured in the book. Not long after Garland made that piece, he realized that exhibiting it in Chicago seemed like preaching to the choir, so he loaded it into his pickup truck and traveled around the country, using it as a means of initiating dialogue. Art can be a means to begin those vital conversations.

SD: That brings me to your work as a librettist, which also addresses the gun issue. Tell me about Inheritance, the chamber opera you collaborated on. Have you always had a background in music, as well, or did you come to opera through poetry?

MD: For Inheritance, I was asked to collaborate with a creative team by a friend, the composer Lei Liang. I'd never written a libretto before and encountered an additional challenge when Lei asked me to determine the opera's subject matter. Gradually, I stumbled upon the biography of Sarah Winchester, the heiress to the Winchester gun fortune. The legend goes that she was told by a psychic to move west and begin building a house that would need to be under constant construction, or the ghosts of those killed by her family's guns would have revenge.

This struck me immediately as a powerful metaphor for America: that our response to our inherited violence is not active change, but rather the perpetual construction of a labyrinth-like, ever-expanding home. After completing the opera, I just couldn't relinquish that story and so adapted some of the elements of the libretto — including my own tour of the Winchester mansion — into the poem ["Portrait of America as a Friday the 13th Flashlight Tour of the Winchester Mystery House"] that appears in the book.

SD: Your website hints at a new project in the works, "Missing Department." What stage are you at in the process?

MD: I've been collaborating on that project with my wife — the artist Ligia Bouton — for the past year and a half, and we're in the process of finalizing an exhibition of the work for A.P.E. [Ltd.] Gallery in Northampton, [Mass]. Ligia discovered a regular column of missing person ads in pulp Western fiction magazines from the early 20th century. The ads read like novels in haiku form, with these compressed raw lines of desire and longing, resentment and love.

We started responding to a selection of the ads: She would make visual art using the original pages of the magazine in which the ad appeared, and I would apply erasure poetry techniques to a single story from within the issue. I created those pieces not long after completing the manuscript of The Dug-Up Gun Museum, and it felt cathartic to spend time erasing the text of narratives that frequently involved gun violence — in order to find a different kind of voice, and human engagement, tucked there within its words.

This interview was edited and condensed for clarity and length.

The original print version of this article was headlined "Plowshares Into Swords | Matt Donovan's The Dug-Up Gun Museum delves into the American obsession with firearms"

Related Locations

-

Norwich Bookstore

- 291 Main St., Norwich Upper Valley VT 05055

- 43.71343;-72.30851

-

802-649-1114

802-649-1114

- www.norwichbookstore.com

Related Stories

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

More By This Author

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.

- 1. Legislature Advances Measures to Improve Vermont’s Response to Animal Cruelty Politics

- 2. A Former MMA Fighter Runs a Wildlife Rehabilitation Center in Cabot News

- 3. This Manchester Center Family Is a National Show Horse Powerhouse Animals

- 4. Welch Pledges Support for Nonprofit Theaters Performing Arts

- 5. Pet Project: Introducing the Winners of the 2024 Best of the Beasts Pet Photo Contest Animals

- 6. Q&A: Downtown Montpelier Transforms Into PoemCity Every April Stuck in Vermont

- 7. A Burlington Celebration of Nature Helps Citizen Scientists Connect With — and Count — the City's Nonhuman Residents Animals

- 1. How a Vergennes Boatbuilder Is Saving an Endangered Tradition — and Got a Credit in the New 'Shōgun' Culture

- 2. Video: The Champlain Valley Quilt Guild Prepares for Its Biennial Quilt Show Stuck in Vermont

- 3. Waitsfield’s Shaina Taub Arrives on Broadway, Starring in Her Own Musical, ‘Suffs’ Theater

- 4. Video: 'Stuck in Vermont' During the Eclipse Stuck in Vermont

- 5. Pet Project: Introducing the Winners of the 2024 Best of the Beasts Pet Photo Contest Animals

- 6. This Manchester Center Family Is a National Show Horse Powerhouse Animals

- 7. Crossing Paths: An Eclipse Crossword 2024 Solar Eclipse