Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

-

Education

Education Bill Would Speed up Secretary Search…

-

News

Middlebury College President Patton to Step Down…

-

News

Overdose-Prevention Site Bill Advances in the Vermont…

- 'We're Leaving': Winooski's Bargain Real Estate Attracted a Diverse Group of Residents for Years. Now They're Being Squeezed Out. Housing Crisis 0

- Aggressive Behavior, Increased Drug Use at Burlington's Downtown Library Prompt Calls for Help City 0

- An Act 250 Bill Would Fast-Track Approval of Downtown Housing While Protecting Natural Areas Environment 0

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

Recalling the Flu Pandemic of 1918

Published February 28, 2018 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated March 8, 2018 at 10:48 a.m.

click to enlarge

- Courtesy Of University Of Vermont Special Collections, Bailey/howe Library

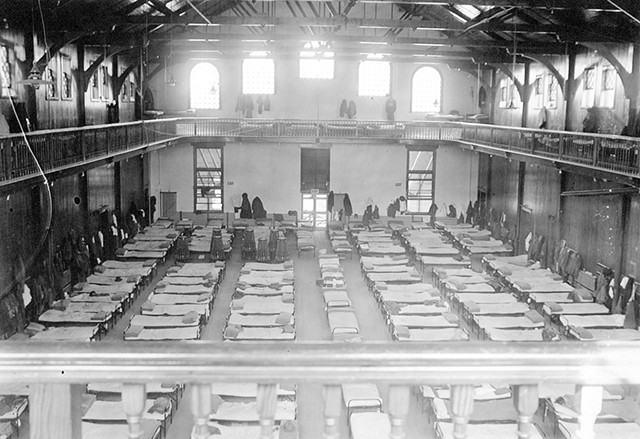

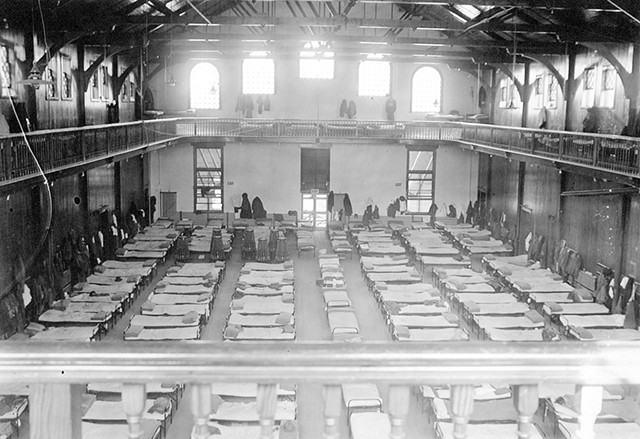

- The University of Vermont gymnasium as a temporary infirmary during the 1918 Spanish influenza pandemic

Vermont is in the midst of its worst influenza season since the H1N1 swine flu pandemic of 2009. The Vermont Department of Health reports that the flu is now widespread throughout the state, as it is across most of the nation. As of February 16, at least 84 pediatric deaths nationwide were attributed to the illness since October 1, though none has occurred in Vermont, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Vermonters suffering through fevers, chills, body aches, nausea, coughing and sore throats — not to mention the logistical headaches of caring for sick family members — undoubtedly feel like they have it bad. Look back a century, though, and suddenly the 2018 flu season seems comparatively tame.

This year marks the centennial of the Spanish influenza pandemic, which claimed an estimated 50 million lives worldwide. Though the 1918 Spanish flu had a devastating impact on Vermont, it faded from our collective memory almost as quickly as it appeared.

Today, ask the average Vermonter about the state's worst-ever natural disaster, and you'll probably hear one of three weather events cited: Tropical Storm Irene in 2011, the ice storm of 1998 or the Great Flood of 1927.

Of the three, the '27 flood was the deadliest, claiming 84 lives and destroying much of the state's vital infrastructure. That death toll pales in comparison to that of the Spanish flu, which struck Vermont without warning in the fall of 1918 and tore through the population like a grassfire. That year, one in four deaths in Vermont was caused by influenza or its complications, usually pneumonia.

By the time the pandemic subsided late in 1919, it had claimed the lives of 2,146 Vermonters — more than twice as many as were killed in all the wars of the 20th century combined. In fact, of the 629 Vermonters who died in World War I, many succumbed not to wounds suffered on the battlefield but to influenza, or "the grippe," as it was commonly called.

History books still refer to that pandemic as the "Spanish" flu because newspapers in Spain were among the first to report it. However, historians now believe that the disease originated in the United States. According to the 2017 PBS "American Experience" documentary "Influenza 1918," the first recorded cases appeared on March 11, 1918, at Fort Riley, Kan. That day, a U.S. Army private showed up at the infirmary with a fever, sore throat and headache. By noon, the hospital had more than 100 cases and, within a week, 500 — including 48 deaths.

In New England, the deadly disease struck with a vengeance in September 1918 at Fort Devens, Mass., just as American troops were preparing to deploy to Europe. Accounts of the disease from Vermont soldiers were included in a book published immediately after the war at the behest of the 1919 Vermont legislature, Vermont in the World War: 1917-1919, edited by John T. Cushing and Arthur F. Stone. One such account told of casualties mounting even before transport ships left port:

The 57th Pioneer Infantry, a regiment formed from the nucleus of the 1st Vermont Infantry, was attacked by the "flu" just as the organization was preparing to embark for overseas service. On the march to the docks the victims fell on all sides. Some of the stricken, in a desperate and pitiful effort to keep with the organizations, threw away rifles and packs and, gasping for breath and reeling from the deadly weakness, staggered along with their comrades until their failing bodies could endure no more. A flock of ambulances followed the column picking up those who fell. There could be no turning back, however, as the regiment was needed in France.

Descriptions of the transatlantic crossing are harrowing. Col. Ernest W. Gibson Sr., commander of the 57th, recalled the horrors he witnessed aboard the transport ship Leviathan:

The conditions during the night cannot be visualized by anyone who has not actually seen them. Pools of blood from severe nasal hemorrhages of many patients were scattered throughout the compartments, and the attendants were powerless to escape tracking through the mess because of the narrow passages between the bunks. The decks became wet and slippery, groans and cries of the terrified added to the confusion of the applicants clamoring for treatment, and altogether a true inferno reigned supreme.

Conditions back home soon became equally grim. Vermont's civilian population fell victim to a disease that struck without warning and, unlike previous epidemics, attacked people in the prime of their lives rather than the very young and very old. According to numerous accounts, a person could feel healthy in the morning and be dead by nightfall.

Of the 43,735 cases reported in Vermont in 1918 alone, 1,772 people died — or about 4 percent of those who got sick. Vermont's high mortality rate was consistent with the findings of a CDC study of the 1918 pandemic, which found that the Spanish flu was far more lethal than previous flu outbreaks and the worst of the 20th century.

Michael Sherman, editor of Vermont History Journal and one of the few historians who's written about the pandemic's effects on Vermont, explained in an interview that the disease spread quickly via the transportation centers of St. Johnsbury, St. Albans, White River Junction, Rutland and Burlington.

As more people fell ill, public libraries, churches, schools and government buildings were converted into makeshift infirmaries. The University of Vermont postponed its fall semester, Middlebury College was quarantined and the Vermont Supreme Court canceled its October term.

Compounding the problem was a dearth of doctors and nurses. Because many had already deployed overseas or were serving at military bases elsewhere, UVM medical students and retired nurses and physicians were pressed into service.

Rachel Muse, a senior archivist with the Vermont State Archives and Records Administration, researched the history of the Spanish flu in Vermont last summer, "not realizing at the time," she noted, "that flu was going to be such a big story this year."

Using only documents culled from state records, Muse assembled a compelling history of September and October 1918 in Vermont. That fall, governor Horace Graham received a telegram from Calvin Coolidge, who was acting governor of Massachusetts, essentially begging Graham to send medical reinforcements to help with the epidemic. Like most states, however, Vermont had none to spare.

"At the Vermont State Hospital," Muse said, "so many doctors and nurses became ill that the patients basically stepped in and were caring for each other and the staff who were ill."

On October 4, 1918, the governor ordered the closing of all Vermont schools, churches, "picture houses," dance halls and other public gathering places until further notice. "Many cities and towns had already taken this step locally," Muse added, "but at this point, they basically shut down everything that they could."

Nevertheless, little could be done to slow the spread of the disease or treat its victims, Sherman said. At the time, virtually nothing was known about viruses or their transmission; it would be another decade before the discovery of penicillin, which could treat ancillary infections such as bacterial pneumonia.

"The [flu] treatments were all over the place, and doctors didn't really have any protocols," Sherman said. That fall, Vermont's newspapers were filled with ads for locally made patent medicines, many of which contained alcohol or opium and did nothing but sedate the dying.

Though virtually no Vermont town was spared, Sherman said some of the highest concentrations of deaths occurred in Barre and Montpelier. There, the disease killed numerous granite workers, whose lungs were already compromised by silicosis caused by years of inhaling stone dust.

"The process of getting bodies into the ground was as much of a problem as administering to the sick," Sherman said. By late October, Vermont was experiencing such a shortage of coffins that wicker ones were being used — and reused. Temporary coffins were used to transport bodies to families, then whisked back to train stations to transport more dead. That fall, most Vermonters didn't hold real funerals, fearing that such gatherings would further spread the disease, Sherman noted.

"I think that's one of the reasons we don't hear a lot about it," Muse suggested of the pandemic. "People got through it and then went about their business. It's amazing how resilient people are after two months of this horrible flu sweeping through town. And then suddenly it's gone from the newspapers, and everything seems to go back to normal."

One explanation for Vermont's collective amnesia about the Spanish flu is its timing. The epidemic was just beginning to subside as the armistice was signed on November 11. Like most Americans, Vermonters celebrated the end of the Great War, which was a much bigger news story than the end of the flu, even though the pandemic claimed five times as many American lives.

Today, the human toll of the Spanish flu in Vermont can be seen carved in stone. Walk through Barre's Hope Cemetery or Montpelier's Green Mount Cemetery, and you'll find entire sections of gravestones etched with the year 1918.

Did the pandemic have other enduring effects on Vermont? Soon after it ended, Muse said, the Vermont legislature passed a bill to consolidate the jobs of town health officers into several public health districts around the state, requiring those officers to be doctors. However, that public health reform was short-lived. In 1923, Muse said, the legislature reversed course and returned that authority to the towns.

For his part, Sherman suggested that Vermonters better remember the Great Flood of '27 because the subsequent recovery took far more time and resources. Though the death of more than 2,000 Vermonters from the Spanish flu was tragic, he said, it was handled with typical Yankee stoicism: "You put up grave markers and you went on."

Something to keep in mind as you down Theraflu and binge-watch Netflix during your own flu recovery this season.

The original print version of this article was headlined "Caught in the Grippe"

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

Tags: History, Spanish influenza pandemic, influenza, flu, the grippe, illness, disease

More By This Author

About The Author

Ken Picard

Bio:

Ken Picard has been a Seven Days staff writer since 2002. He has won numerous awards for his work, including the Vermont Press Association's 2005 Mavis Doyle award, a general excellence prize for reporters.

Ken Picard has been a Seven Days staff writer since 2002. He has won numerous awards for his work, including the Vermont Press Association's 2005 Mavis Doyle award, a general excellence prize for reporters.

Speaking of...

-

Mirroring a National Trend, RSV Hospitalizations Rise in Vermont

Oct 25, 2022 -

As Students Shed Masks, Common Childhood Illnesses Resurge in Classrooms

Apr 13, 2022 -

Vermont Centenarian Florilla Ames Recalls 1918 Pandemic

May 13, 2020 -

Testing Site Opens in Putney; Library Suspends Pickup Service, Catholic Churches and Shrines to Close: Coronavirus News in Vermont

Mar 29, 2020 -

Lyme on the Rise

Jul 3, 2018 - More »

Comments

Showing 1-1 of 1

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.

- 1. Video: Visiting the Wind Phone at the Lanpher Memorial Library in Hyde Park Stuck in Vermont

- 2. Woodstock Poetry Festival Replaces Bookstock Books

- 3. STRUT! Fashion Show Returns After Four-Year Hiatus Culture

- 4. Shaina Taub's 'Suffs' Earns Six Tony Nominations, Including Best Musical Performing Arts

- 5. Bianca Stone Named New Vermont Poet Laureate Poetry

- 6. Student Film Documents Failed Plan to Cut Books From Vermont State University Libraries Film

- 7. Amalia Angulo’s Drawings at Kishka Gallery Suggest and Question a 'Peaceable Kingdom' Art Review

- 1. How a Vergennes Boatbuilder Is Saving an Endangered Tradition — and Got a Credit in the New 'Shōgun' Culture

- 2. Video: The Champlain Valley Quilt Guild Prepares for Its Biennial Quilt Show Stuck in Vermont

- 3. Waitsfield’s Shaina Taub Arrives on Broadway, Starring in Her Own Musical, ‘Suffs’ Theater

- 4. This Manchester Center Family Is a National Show Horse Powerhouse Animals

- 5. Video: 'Stuck in Vermont' During the Eclipse Stuck in Vermont

- 6. Pet Project: Introducing the Winners of the 2024 Best of the Beasts Pet Photo Contest Animals

- 7. Vermont Poet Sydney Lea on His New Collections of Verse and Prose Books