Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

-

Education

Scott Official Pushes Back on Former State…

-

News

Burlington Budget Deficit Balloons to $13.1 Million

-

Education

Senate Committee Votes 3-2 to Recommend Saunders…

- Court Rejects Roxbury's Request to Block School Budget Vote Education 0

- Norwich University Names New President Education 0

- Media Note: Mitch Wertlieb Named Host of 'Vermont This Week' Health Care 0

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

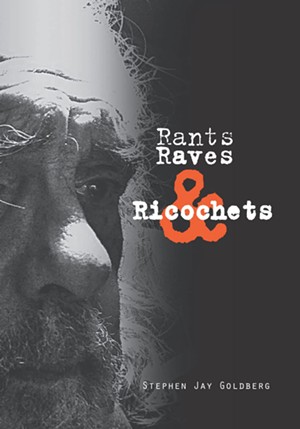

Talking With Stephen Jay Goldberg About His New Book, 'Rants Raves & Ricochets'

Published August 17, 2022 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated August 17, 2022 at 10:06 a.m.

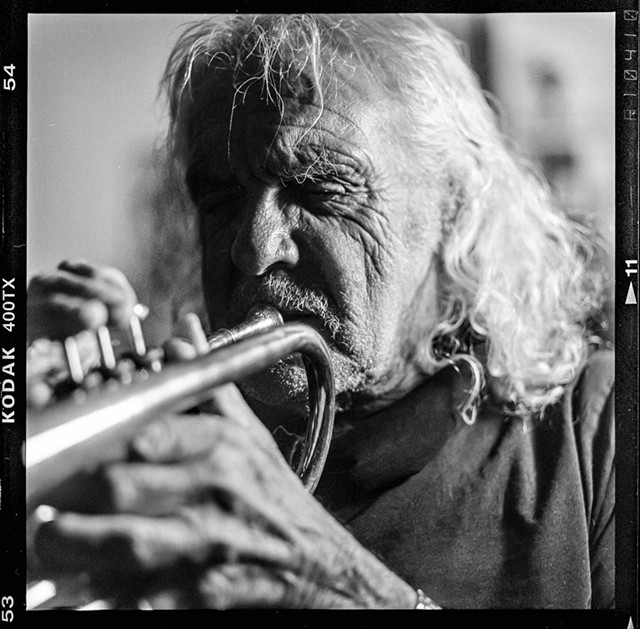

When I met Stephen Jay Goldberg in 2007, I knew him first as a poet, one of the regulars at the Monday night "no guitar" open mic at Burlington's Radio Bean. Chain-smoking in a leather jacket, with disheveled shoulder-length silver curls and a goatee, Steve seemed like an ideal emissary from New York City's 1960s bohemia. The poems he read were filled with down-and-out characters, jazz musicians, lovers, seekers and losers. Usually he performed two pieces, the first one funny, filled with self-deprecating punch lines and sexual innuendo. Once he had put the audience at ease, his second piece would stick a knife in us.

I didn't know then that Goldberg is a musician by trade who has been a fixture of Vermont's artistic landscape since the 1980s. He's played trumpet and flügelhorn all over the world, including in the backing bands of Stevie Wonder, Little Richard and Chuck Berry. With his late wife, Rachel Bissex, he toured as the opening act for Ray Charles.

In late May of this year, I hydrated, bought a fresh pack of cigarettes and visited Steve's home in Burlington's New North End, where we spoke about his latest book, Rants Raves & Ricochets, and consumed a quantity of vodka.

Born in Queens, N.Y., Goldberg studied at the Manhattan School of Music. He came to Vermont as the musical director of Nimbus Dance for a residency at Johnson State College (now Northern Vermont University). There, playwright John Ford Noonan encouraged him to pursue playwriting. Goldberg has since produced more than two dozen plays and cofounded Burlington's Off Center for the Dramatic Arts with Paul Schnabel, John D. Alexander and Genevra MacPhail. Burlington's Fomite Press published a selection of Goldberg's plays, Screwed, in 2013.

Rants Raves & Ricochets, also published by Fomite, brings together decades of poems, memoirs and a novella-length work of fiction.

"I have cartons of this stuff," Goldberg told me over a few rounds of Absolut vodka and Coca-Cola Zero Sugar. "Enough for 10 more books."

Goldberg is a natural storyteller. The poems in Rants Raves & Ricochets transport the reader into a lurid world of 1960s jazz musicians and junkies, booze and bars, jam sessions and lonely love affairs. "I wonder if he ever / put the needle in the lost love tattoo / I would have / I'm sure he did / Frank was a romantic," Goldberg writes in "Frank Dupree."

One of the most moving pieces in the book, this poem recalls a tenor sax player who worked as a longshoreman. Frank invites the author, then a young trumpet player, to an all-night jam session on his Lower East Side rooftop, where they drink cheap wine, play "thousands of choruses" and pass out until the sun wakes them.

Goldberg isn't afraid to show us both the agony and the ecstasy, though: Ultimately, Frank overdoses, and his body is found "not by his friends or lovers / but by the stink of his rotting corpse."

Fans of writers such as Jack Kerouac and Chuck Palahniuk will eat up Rants Raves & Ricochets like candy. Readers who find the Beats passé or groan at their male gaze may be surprised by how much emotional depth Goldberg adds to his stories. Along with telling eccentric tales of drinking, globe-trotting and promiscuity, the author tenderly describes moments such as being bathed as a small child by his father and explores the complex emotional dynamics of his household.

Unsurprisingly, the seasoned playwright divides his book into a loose three-act structure, beginning with recollections from childhood. His preoccupation with death began early, we learn: The opening poem recounts a memory from age 9 in which the narrator wakes from a pleasant dream to find that "two men in dark suits were coming up the stairs to my / bedroom carrying a coffin." This in turn is a dream from which he wakes, Inception-style. "Till this day I have never known / if I am awake or dreaming. / About to wake up," the poem concludes.

A profound sense of loss haunts Goldberg's writing. "[S]o where the fuck is Bach / where is Beethoven," he asks in "It's the Next Thing," a long poem that laments the shallowness and accelerating pace of modernity.

In "Dad's Darkroom," a slice of memoir-prose, he describes watching his father, a furrier by trade, smoke a cigar while working in his darkroom. Eventually, his father's business in Manhattan's Fur District went belly-up. He "would walk around the apartment like a caged animal," Goldberg writes. "I know that's what killed him at 57, the idea of failure, to not provide for his family the way he had."

This theme of loss is explored more in depth, albeit in fictionalized form, in the novella that makes up the middle section of the book. Titled "Black and Whites," it's narrated by a suicidal painter, Sidney, who lives in relative bliss with his wife in upstate New York. In the opening scene, he washes down pills with a bottle of Scotch and torches all of his work — huge black-and-white paintings that he paints with a roller — in a bonfire.

From there, things get steadily worse and more surreal. Sid's wife gives him the car and tells him to get lost, precipitating a picaresque journey of car crashes, sexual encounters and a brutal murder scene worthy of Georges Bataille's controversial 1928 novella Story of the Eye.

"I have some friends who really didn't like it. And some loved it. I can't even remember writing it," Goldberg said.

Somehow, "Black and Whites" is also laugh-out-loud funny at times. At one point, the protagonist gets interrogated by a man claiming to be Sammy Davis Jr.'s rabbi. After a bit of back-and-forth, he says, '"Let's cut the crap, Sidney, are you a Jew?"' The conversation that ensues feels like a Socratic dialogue composed in the style of a profane, absurdist comedy. "I think you should fuck off," Sidney tells him. "I think you're full of shit, that's what I think. Rabbi."

Design-wise, the book is defiantly experimental. Throughout, font sizes and styles shift, sometimes even from stanza to stanza. Photographs, scraps of paper, handwritten grocery lists, X-rays and medical files illustrate Goldberg's stories of his family history and health, rendering them instantly more tangible and personal.

"Down in Mexico, this guy [Warren Clark] kept showing up at my gigs, and it turned out he's a book designer. So I said, 'Yeah, man, let's do it,'" Goldberg explained to me, gesturing vaguely into the distance as if things like that happen all the time. Which, if you're Steve Goldberg, they seem to do.

Our conversation was peppered with anecdotes like this one, often told apropos of nothing and in the natural cadence of a standup comedian. While getting ice for another round of drinks, for example, Goldberg said, "My ex-ex-wife had this gorgeous house in Westchester with an ice machine. A friend from the city called me up, asked what I was doing up there. I said, 'I'm just trying to keep up with the ice machine.'"

Then Goldberg informed me that what we were drinking wasn't actually Absolut. "What I do is, I buy the cheap stuff and pour it in," he explained. "It makes the vodka very happy to be in a glass bottle in the icebox, you know? So that's what I do. It makes me a little happy, too."

The original print version of this article was headlined "Goldberg Variations | Talking with Stephen Jay Goldberg about his new book, Rants Raves & Ricochets"

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

More By This Author

Speaking of...

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.

- 1. A Former MMA Fighter Runs a Wildlife Rehabilitation Center in Cabot News

- 2. Legislature Advances Measures to Improve Vermont’s Response to Animal Cruelty Politics

- 3. This Manchester Center Family Is a National Show Horse Powerhouse Animals

- 4. Welch Pledges Support for Nonprofit Theaters Performing Arts

- 5. Q&A: Downtown Montpelier Transforms Into PoemCity Every April Stuck in Vermont

- 6. Pet Project: Introducing the Winners of the 2024 Best of the Beasts Pet Photo Contest Animals

- 7. A Burlington Celebration of Nature Helps Citizen Scientists Connect With — and Count — the City's Nonhuman Residents Animals

- 1. How a Vergennes Boatbuilder Is Saving an Endangered Tradition — and Got a Credit in the New 'Shōgun' Culture

- 2. Video: The Champlain Valley Quilt Guild Prepares for Its Biennial Quilt Show Stuck in Vermont

- 3. Waitsfield’s Shaina Taub Arrives on Broadway, Starring in Her Own Musical, ‘Suffs’ Theater

- 4. Video: 'Stuck in Vermont' During the Eclipse Stuck in Vermont

- 5. Pet Project: Introducing the Winners of the 2024 Best of the Beasts Pet Photo Contest Animals

- 6. This Manchester Center Family Is a National Show Horse Powerhouse Animals

- 7. Crossing Paths: An Eclipse Crossword 2024 Solar Eclipse