Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

-

Education

Scott Official Pushes Back on Former State…

-

News

Burlington Budget Deficit Balloons to $13.1 Million

-

Education

Senate Committee Votes 3-2 to Recommend Saunders…

- Court Rejects Roxbury's Request to Block School Budget Vote Education 0

- Norwich University Names New President Education 0

- Media Note: Mitch Wertlieb Named Host of 'Vermont This Week' Health Care 0

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

Vermont's Female Tattoo Artists Are Making a Mark

Published May 10, 2017 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated November 7, 2017 at 12:41 p.m.

Not so long ago, tattoos were primarily the provenance of the rough-and-tumble crowd — think convicts and sailors and punks. But, increasingly, indelible ink is as likely to be found on the forearms, ankles or lower backs of lawyers and accountants as on your average biker, basketball player or barfly. A 2015 Harris Poll found that nearly 30 percent of American adults have at least one tattoo. That's up from 21 percent in 2012 and just 16 percent in 2003.

It's not surprising that millennials are leading the branding boom. Almost half of Americans ages 18 to 35 have ink, compared to 36 percent of Gen Xers and 13 percent of baby boomers. Your granddad's anchor tat from the Navy makes him the one in 10 of elders with eternal epidermal emblems.

Once a symbol of rebellion, tattoos have become mainstream. At the risk of cynicism, it's fair to wonder if not having a tattoo might soon be considered as much a statement as whatever that Chinese character on your shoulder means.

Just as the populations getting tattoos are changing, so are tattoo artists. That is, they're not all guys anymore. Hard numbers are tough to come by, since licensing varies by state and few states track licensees by gender. But, at least anecdotally, more women are gravitating toward the industry. Female artists are now common at tattoo shops around Vermont, and some of those shops are women-owned. Given that women are statistically more likely than men to have tattoos — 31 percent of women, compared to 27 percent of men, per the Harris Poll — some gender balance in the biz is long overdue.

For this story, Seven Days visited four Vermont tattoo shops owned or co-owned by women. We checked out Meredith Muse's mystical home-based studio, Shady Lady Tattoo Parlour, in Moretown. At Contour Studios in Newport, we chatted up three hometown heroes who are trying to make their city a better place, one tattoo at a time. In St. Albans, the ladies at Luminary Ink Tattoos, Body Piercing & Permanent Cosmetics sting the body electric with an astral flair. And in Barre, Rock City Tattoo's Lila Rees puts a piece of her mind into every piece of art on her clients' skin.

— D.B.

The Masochist's Psychologist

"Whenever someone I love dies," says Contour Studios co-owner Katlin Parenteau, "the first thing I want to do is get a tattoo."

Among Parenteau's 19 tattoos is a dagger on her right inner forearm dedicated to her late grandfather. It accompanies a red rose for her mother, Dana Parenteau, who died a little more than a year ago.

"The tattoo artist is the masochist's psychologist," Parenteau muses. "[People get tattoos] for a therapeutic outlet without having to put themselves out there emotionally."

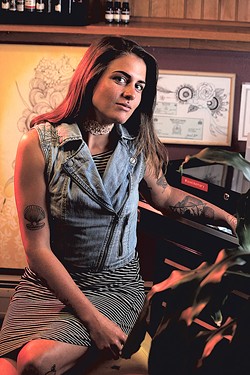

Parenteau, 24, opened the second-floor Newport shop in April 2015 with Dana Morse, 27. Though the two are equal business partners, Parenteau and fellow Contour artist Anna LeBlanc, 26, attribute much of their growth in the industry to Morse, who has apprenticed both women.

"If it wasn't for him," Parenteau says, "I wouldn't have progressed the way I have." She adds that Morse's reputation has bolstered the shop's clientele.

Morse has been tattooing in the region for nearly 10 years. "I know everybody, and everybody knows me," he says. Though he didn't set out to become a tattoo artist, while he was training to be an engineer some friends decided they needed him to ink their tats.

"They were so dead set on having me do it," he recalls, "that they bought me a kit and showed up at my house with a six-pack and some Jameson.

"It just felt right," Morse continues. "I wasn't good at it, but I figured I could get good at it." When he was laid off from his job at North Country Engineering in 2009, he threw himself into tattooing and earned his license the following year.

Morse, LeBlanc and Parenteau have all made art from a young age. LeBlanc recalls imitating manga styles, admitting she's "the nerdiest" of the bunch. Parenteau's colorful and often mystical illustrations reflect her personality: gregarious and on the wild side.

All three artists grew up in the Northeast Kingdom and attended North Country Union High School. In conversation, they display a fierce sense of community that's shaped by the region's darker aspects: economic depression and opiate addiction.

"People drop like flies around here," says Parenteau, whose left thigh bears the word "Northeast" in cursive script. She pulls up an iPhone photo of a Watchmen-themed tattoo she did on a friend's arm; it was both a cover-up (of the Nirvana smiley face) and a memorial to friend Keith O'Keefe, who died in 2015 at age 27.

Many tattoos commissioned at Contour are cover-ups or memorials. Morse says he usually offers a 20 to 25 percent discount for the latter — because he often knows the client as well as the deceased.

"I'm not trying to make money off of your dead friend," he says. He has also discounted tattoos that cover cutting scars, particularly for young women. "Those scars could cost them a job in the future," he says, "because they [might] seem unstable."

And there's no shortage of folks who come in with bad tattoos they've gotten elsewhere, often from unlicensed acquaintances. "I fix so much of their crap," Morse comments.

Contour gives back more than ink to its community. Parenteau notes donations the shop has made to local causes — including the motorcycle rally Cruzin' for Cancer and the Eli Goss Memorial Ice Fishing Tournament. She also initiated a political essay contest, offering $150 in tattooing credit for her favorite submission. Parenteau selected Ethan Allen Institute staffer Shayne Spence for his Republican argument in favor of legalizing marijuana. VTDigger.org published the essay.

Ultimately, Contour's artists are forging a path that allows them to make a living through making art while also elevating their hometown.

Parenteau's dreams are many: to be featured in Inked Magazine, to change Vermont law to allow tattoo conventions, to buy a building. LeBlanc says she just wants to "make a good living doing something I actually like."

Morse's ambition is similarly humble: "I want to be a shop that's known for its artwork."

— R.E.J.

Lights for Each Other

Luminary Ink Tattoos, Body Piercing & Permanent Cosmetics in St. Albans has a celestial feel. The wrought-iron benches, plants, high ceilings and soft jazz music impart a soothing air more common to a spa or salon. The display case full of earrings might indicate a store, the padded tables a massage studio. But the wall-size mural of the Orion Nebula is, surprisingly, key to understanding this universe.

"I wanted to bring the outside inside," says Luminary owner Sara King. Her goal for the shop, she explains, was to create "an inspirational space for people to relax in and a safe place where their ideas about body art were respected." The mural serves as a backdrop for photographs of completed tattoos and a reminder of what she calls "the intuitive nature we all have as lights for each other."

King, 52, and her three employees pride themselves on treating clients well and putting them at ease. Ryann Schofield, 32, has been a tattoo artist for five years and has worked with King for the past three. "I make sure to communicate very carefully about what people want and how they want it," she says.

King's 30-year-old daughter, Nina King, is the shop's body-piercing specialist. Mary Frances Wrixon, 25, is King's tattoo apprentice.

Sitting in the shop after hours, Sara King recounts the moment she decided to become a tattoo artist.

"I had gone through a series of tragedies," she says, echoing the reason many people choose to get tattoos — divorce, death, profound life changes. "Returning to painting and drawing helped me recover from depression."

The day she decided to look for a job in the arts, she found an opening at a new tattoo studio. Chris Bijolle of Tribal Eye Tattoo (now Sacred Sparrow Tattoo) took her on as an apprentice in 2003, and the rest is herstory.*

Being the only woman in a male-dominated industry "sure wasn't easy," says King. But she was licensed by 2004 and opened her own shop, Sara's Tattoo Parlor, in 2005. At the time, she estimated that she was only the seventh female tattooist in the state.

In 2015, King moved the business to its current location, added body piercing and permanent cosmetics, and changed its name. She is certified in tattooed makeup, which requires specialized training.

"About 10 percent of our clients are interested in eyeliner or eyebrows," she says. King also provides areola and nipple restoration for breast cancer survivors.

Those services attract more women than men, but Luminary advertises itself as gender-neutral and caters to all (legal) ages. It's also a custom shop: King and Schofield create original designs for clients, including hand drawing, rather than relying on preprinted flash art.

"We can follow the body's contours," says Schofield, "accentuating or hiding what people want."

Getting tattooed is an intimate and sometimes painful experience. With that pain comes the body's natural response: a kick of adrenaline, then pain-relieving endorphins. Studies have shown that these chemicals can create an emotional high or sense of euphoria.

"We can see it," confirms King. "[Clients are] very tense, and they're talking a lot. And then all of a sudden they mellow out and get quiet and relax, and they aren't hyper or nervous anymore."

While this response helps clients endure tattooing, it can create problems for those who don't understand the physiology of what's happening. "We get men who come back who feel connected to us," says Schofield.

"They think we're interested in them," explains King. "You're causing them pain, and you're helping them get through it."

This confluence of chemicals and intimacy requires that the artists set clear boundaries and "stay humble," says Schofield.

So, how many tattoos do these women have?

"We're at body percentage, not numbers," says King, estimating that 30 to 40 percent of her body is tattooed.

"I'm at about 10 percent," says Schofield. "But I have time."

— E.M.S.

Casting a Spell

For Meredith Muse, owner of Shady Lady Tattoo Parlour in Moretown, the story behind a tattoo is inextricable from the tattoo itself. "I offer not just tattoo sessions," she says. "Sometimes I offer sessions that are a little more in-depth around setting a spiritual intention around the tattoo."

For example, if someone were three months sober and wanted to get a tattoo to commemorate that, Muse says she and the client would "speak formally" about the milestone before beginning the tattoo. She believes that holding her subject's intentions in her mind while tattooing is helpful, "because it's sort of this transformation process that has this energy behind it."

If that sounds vaguely mystical, it is.

"[Tattooing] is a form of magic and spell-casting," says Muse, 53. "I like to think of it as casting a spell into someone's skin, or a prayer."

In many neo-pagan practices, spells are simply dedications or invocations that rely less on eye of newt and more on the power of conjuring a reality through positive thinking. Just as affirmations are used to rewire the brain away from bad habits, spell-casting functions on the premise that if you believe in something, eventually it will manifest.

About 25 percent of Muse's clients take her up on that aspect of her practice, she says. Some set up an altar to focus on during the session; others bring in photos. And sharing stories is key to the process.

"For me, the story is a huge part of the work," Muse says. "I've made some of my best friends through tattooing."

Muse operates her shop in her house, which she bought after Tropical Storm Irene. Much of the rambling wooden structure had been devastated by that tempest, which ripped through Vermont in August 2011. The first thing she did was gut and repair one room to serve as her tattoo studio.

"There was water up to five feet in here," she says, seated in a padded leather barber's chair and surveying the colorful collection of books, neatly organized inks and trailing plants hanging in the window.

Once Shady Lady was up and running, Muse was able to fund repairs for the rest of the house. Her barn serves as a DIY event space hosting poetry, music and theater. Every fall, Muse organizes a group ritual called "A Night of Spirit Remembering," designed to honor the dead.

The space is heavily infused with symbolism and spirituality, which Muse draws into her work. She practices Reclaiming, a neo-pagan spiritual path that combines traditional witchcraft, feminism and political activism. "It's very intuitive," Muse says. "And there's very little dogma."

As her surroundings suggest, the artist's specialty isn't a certain style of tattoo or color scheme: It's cultivating the environment in which the tattoo is made. Creating a safe atmosphere in which to process emotion while getting inked was on Muse's radar from the start.

Early in her career, while working in another shop, she recalls giving tattoos to a young couple who were grieving the loss of their baby. The vibe of the walk-in shop, Muse says, was not conducive to that emotional process — think loud music, harsh language and little privacy. So, once she had completed her apprenticeship, in 2005, she vowed to "find a way to create a more private venue with a more intentional offering."

Currently, two other licensed tattooists offer ink through Shady Lady: Esmé Hall and Matthew Manning. Muse's sole apprentice is Evan Book.

Muse got into the game late in life — she didn't start apprenticing until she was 38. In part that was because the industry wasn't as welcoming to women in the past.

"It's changed a lot," she says. "It's amazing to me how different things are and how quickly the art of tattoo is moving forward."

— S.W.

Animal Instinct

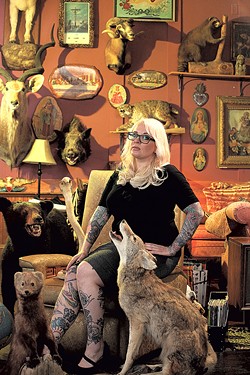

Walk into Lila Rees' shop, Rock City Tattoo, in Barre and you might feel like you've entered a strange synthesis of natural history museum and Victorian parlor. The deep-rose-hued walls are adorned with the taxidermy heads and bodies of a ram, raccoon, beaver, onyx, kudu, boar and skunk, among other creatures. Ornate pink and brown velvet couches draped with furs impart a luxurious lounge feel. Numerous varnished, wood-slice Jesus paintings add flair.

The 37-year-old tattoo artist has occupied this mashup den, located in an old brick school building, for five years. Before that, she rented space above Vermont's only strip club, the now-defunct Planet Rock.

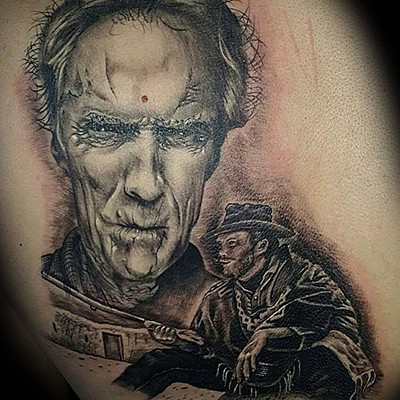

Rees is an avid motorcyclist and, as her studio attests, an equally enthusiastic collector of taxidermy. As a tattoo artist, her focus is, not surprisingly, on animal portraiture. Rees' portfolio reveals delicately shaded renditions of big cats, horses, birds of prey, dogs and more. Color is sparse — Rees primarily employs black ink for shading and precise line work. And the surrounding menagerie isn't just for decoration.

"I had to fix a tattoo of a black bear on a lady, and I had one here," Rees notes, pointing to a small bear cozied up to the brown couch. "I was able to use [this] as reference."

She adds that not all of her preserved animals are worthy of their likeness on someone's skin.

"Depending on the quality of the taxidermy, some of them are more lifelike than others," Rees concedes. And nobody, she adds, wants a crazy-looking raccoon on his or her body.

Rees launched Rock City Tattoo in 2008. It's a private tattoo studio — she's the only artist — as opposed to a walk-in shop.

That distinction gives Rees some control over what jobs she'll take, and the overall satisfaction of her clients. She readily offers her opinions on their ideas — which is not always well received. But she says her candid approach generally results in a better tattoo.

"I had a kid in here a few summers ago," Rees recalls. "He said he'd heard some stuff about me. I said, 'What, that I'm expensive and I'm a bitch?' He said, 'Well, I heard that you're opinionated. And you're the best.'"

Rees attributes gender bias to the notion that she's "opinionated."

"Nobody would say that about a man," she exclaims.

Still, that quality serves Rees well in her practice. Negotiation is a big part of the Rock City Tattoo experience. Weighing in on a client's idea, she says, "isn't about [me doing] what I want to do. It's just [if their idea] makes for a poor-looking tattoo that's not going to hold up over time, what's the point?"

Another aspect of her practice that Rees doesn't advertise is her ability to draw designs freehand — that is, without a stencil. "Sometimes it has to be done," she says, pointing to a watercolor-style feather she did last year that went viral on Instagram.

"You can't do that on a piece of paper and make it fit on a body," she says. "I like tattoos to look organic, like they're just a part of your body, not harsh." The feather is a perfect example: Rees' expressive lines fit naturally on the arm, and the tip curls around the arch of the client's shoulder.

These days clients might bring in tattoo ideas found on social media sites, but the touch of originality from an artist such as Rees can make their design unique.

If there's one thing she wishes people would do before getting a tattoo, it's to look at the artist's previous work. "If you like how it looks, go to that artist," she advises, "and that's the style you're going to get."

— S.W.

Needle to Know: How Vermont Regulates Tattoo Artists

Not just anyone with a cheap tattoo gun and a few bottles of colored ink can hang out a shingle and start etching Celtic knots and cartoon characters onto butts and biceps. Local tattoo artists first must be licensed by the Vermont Office of Professional Regulation. That means the state's 67 licensed tattooists and three permanent-cosmetic tattooists all have experience considered adequate for the practice.

By law, to earn a tattoo license, a person must apprentice for at least 1,000 hours within two calendar years under the direct supervision of a licensed tattoo artist. The latter must be in good standing with the state and have at least three years of experience. The apprenticeship must include successful completion of a three-hour course in "universal precautions" for preventing the spread of infectious diseases and other microbial nastiness that can get under a client's skin.

The good news: There's no written exam to earn a tattoo license in Vermont. The bad news: Tattooists who don't spellcheck their work beforehand are in for a world of hurt from an irate customer after they ink, say, "No regerts."

Additionally, every tattoo and body-piercing shop must be inspected prior to opening and is subject to random inspections. If the OPR receives a complaint about a specific inking establishment — for example, for tattooing a minor without parental consent, for inking someone who's intoxicated, or for their own "habitual drunkenness," all of which are illegal — a state inspector is likely to pay a visit.

If a tattooist's license is suspended or revoked, it's usually for criminal conduct, according to Gabe Gilman, the OPR's general counsel. This conduct can include drug dealing or possession, body piercing without a license, or failure to reveal past felony convictions on the state application.

Or, in the case of one careless tattoo artist, for general uncleanliness. According to the OPR's records, that transgression included allowing his dog to be in the room while he was working.

— K.P.

Tat Stats From Vermont and Beyond

- According to the Vermont Office of Professional Regulation, Vermont has 67 licensed tattoo artists and 17 tattoo apprentices. The state has a far smaller number of cosmetic tattooists: three, with just one apprentice.

- 30 Vermonters are licensed body piercers, 19 of whom are also licensed tattoo artists. Half of the state's 10 body-piercing apprentices are also tattoo apprentices.

- Vermont has 21 tattoo-only shops and another 23 businesses that offer both tattooing and body piercing. No shops in Vermont are devoted solely to body piercing.

- According to a 2015 Harris Poll, nearly three in 10 Americans have tattoos. That's up from 21 percent in 2012.

- What's better than one tattoo? More tattoos! According to the same poll, 70 percent of Americans with tattoos have more than one.

- Assuming those national numbers apply, if you live in Burlington or the Northeast Kingdom, you are more likely to have ink than someone who lives in, say, Williston. Roughly one-third of people in both rural and urban areas have tats, compared to just 25 percent of suburbanites.

- Pop quiz: Who is more likely to have tattoos, parents or childless adults? Forty-three percent of American parents are tatted. Just 21 percent of adults without kids have body art — perhaps indicating an aversion to lifelong commitments?

- When it comes to control over our bodies, tattoos are one subject on which Americans of all political stripes seem to agree: 27 percent of Republicans, 29 percent of Democrats and 28 percent of independents have tattoos.

- Twenty-three percent of Americans regret getting a tattoo, up from 14 percent in 2012.

- According to a 2012 study published in the Journal of Sexual Medicine, adults with body modifications — tattoos and/or piercings — typically had their first sexual encounters at a younger age than those without. They were also likely to be more sexually active in general.

- The same study found no difference in sexual orientation, sexual preference, a willingness to engage in risky sexual behavior, or history of abuse between people with body modifications and those without.

- The JSM study did find that people with tats or piercings were four times less likely to be religious.

— D.B.

* Correction, May 11, 2017: An earlier version of this story misidentified the location of Sara King's tattoo apprenticeship. It was with Chris Bijolle of Tribal Eye Tattoo (now Sacred Sparrow Tattoo).The original print version of this article was headlined "Skin in the Game"

Related Stories

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

Tags: Visual Art, cannabis related, Contour Studios, female tattoo artists, Katlin Parenteau, Lila Rees, Luminary Ink Tattoos, Body Piercing & Permanent Cosmetics, Mary Frances Wrixon, Meredith Muse, Nina King, Rock City Tattoo, Ryann Schofield, Shady Lady Tattoo Parlour, tattoo artist, Tattoos, Slideshow, Video

About The Authors

Dan Bolles

Bio:

Dan Bolles is Seven Days' assistant arts editor and also edits What's Good, the annual city guide to Burlington. He has received numerous state, regional and national awards for his coverage of the arts, music, sports and culture. He loves dogs, dark beer and the Boston Red Sox.

Dan Bolles is Seven Days' assistant arts editor and also edits What's Good, the annual city guide to Burlington. He has received numerous state, regional and national awards for his coverage of the arts, music, sports and culture. He loves dogs, dark beer and the Boston Red Sox.

Rachel Elizabeth Jones

Bio:

Rachel was an arts staff writer at Seven Days. She writes from the intersections of art, visual culture and anthropology, and has contributed to The New Inquiry, The LA Review of Books and Artforum, among other publications.

Rachel was an arts staff writer at Seven Days. She writes from the intersections of art, visual culture and anthropology, and has contributed to The New Inquiry, The LA Review of Books and Artforum, among other publications.

Ken Picard

Bio:

Ken Picard has been a Seven Days staff writer since 2002. He has won numerous awards for his work, including the Vermont Press Association's 2005 Mavis Doyle award, a general excellence prize for reporters.

Ken Picard has been a Seven Days staff writer since 2002. He has won numerous awards for his work, including the Vermont Press Association's 2005 Mavis Doyle award, a general excellence prize for reporters.

Elizabeth M. Seyler

Bio:

Elizabeth M. Seyler was a coeditor for the arts and culture section at Seven Days 2021-2022 and assistant editor and proofreader 2017-2021. She's a freelancer writer and editor who holds a PhD in dance and teaches Argentine tango.

Elizabeth M. Seyler was a coeditor for the arts and culture section at Seven Days 2021-2022 and assistant editor and proofreader 2017-2021. She's a freelancer writer and editor who holds a PhD in dance and teaches Argentine tango.

About the Artist

Matthew Thorsen

Bio:

Matthew Thorsen was a photographer for Seven Days 1995-2018. Read all about his life and work here.

Matthew Thorsen was a photographer for Seven Days 1995-2018. Read all about his life and work here.

Speaking of...

-

‘Tattoo Living’ Celebrates Body Art at Bennington Museum

Apr 17, 2024 -

2020 Vermont Holiday Gift Guide

Nov 17, 2020 -

My Girlfriend Wants to Get My Name Tattooed on Her Chest

Aug 26, 2020 -

Inked Over: A Vermont Artist Covers Up Hate Tattoos for Free

Jun 17, 2020 -

As Tattoo Studios Reopen, Clients Express Need for Nurturing

Jun 17, 2020 - More »

Comments (8)

Showing 1-8 of 8

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.

- 1. A Former MMA Fighter Runs a Wildlife Rehabilitation Center in Cabot News

- 2. Legislature Advances Measures to Improve Vermont’s Response to Animal Cruelty Politics

- 3. This Manchester Center Family Is a National Show Horse Powerhouse Animals

- 4. Welch Pledges Support for Nonprofit Theaters Performing Arts

- 5. Q&A: Downtown Montpelier Transforms Into PoemCity Every April Stuck in Vermont

- 6. Pet Project: Introducing the Winners of the 2024 Best of the Beasts Pet Photo Contest Animals

- 7. A Burlington Celebration of Nature Helps Citizen Scientists Connect With — and Count — the City's Nonhuman Residents Animals

- 1. How a Vergennes Boatbuilder Is Saving an Endangered Tradition — and Got a Credit in the New 'Shōgun' Culture

- 2. Video: The Champlain Valley Quilt Guild Prepares for Its Biennial Quilt Show Stuck in Vermont

- 3. Waitsfield’s Shaina Taub Arrives on Broadway, Starring in Her Own Musical, ‘Suffs’ Theater

- 4. Video: 'Stuck in Vermont' During the Eclipse Stuck in Vermont

- 5. Pet Project: Introducing the Winners of the 2024 Best of the Beasts Pet Photo Contest Animals

- 6. This Manchester Center Family Is a National Show Horse Powerhouse Animals

- 7. Crossing Paths: An Eclipse Crossword 2024 Solar Eclipse

![Lila The Tattoo Lady [SIV350]](https://media1.sevendaysvt.com/sevendaysvt/imager/lila-the-tattoo-lady-siv350/u/square/2356456/episode350.jpg)