Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

-

Education

Scott Official Pushes Back on Former State…

-

News

Burlington Budget Deficit Balloons to $13.1 Million

-

Education

Senate Committee Votes 3-2 to Recommend Saunders…

- Court Rejects Roxbury's Request to Block School Budget Vote Education 0

- Norwich University Names New President Education 0

- Media Note: Mitch Wertlieb Named Host of 'Vermont This Week' Health Care 0

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

Lab-Grown Meat Could Help Feed a Climate-Changed World. Newly Launched Burlington Bio Hopes to Take a Bite.

Published October 17, 2023 at 7:14 p.m. | Updated October 25, 2023 at 10:05 a.m.

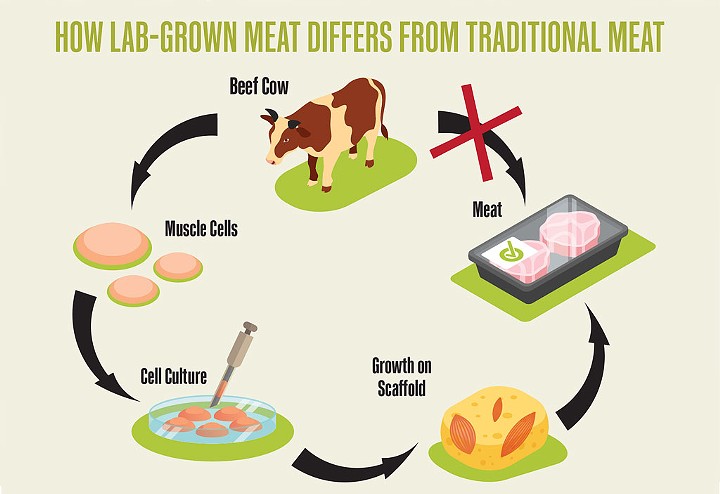

The two mechanical engineers are growing meat from cells extracted painlessly from live animals. Once such cells multiply under tightly controlled conditions, they can be shaped into chicken nuggets or ground into hamburger. The UVM researchers are refining a material that can help grow those cells and also might steer the emerging field to the holy grail of cultivated meat: chicken breasts and whole steaks.

Floreani, a 41-year-old associate professor, directs the Engineered Biomaterials Research Laboratory, part of UVM's College of Engineering and Mathematical Sciences. When the building that now contains the lab went up in the early 1960s, Earth's population was less than half of its current 8 billion, and Julia Child was poised to introduce Americans to a red wine and beef stew called boeuf Bourguignon. The idea that scientists might someday grow that meat in a lab was the stuff of science fiction.

But over the summer, the first lab-grown cultivated meat approved for human consumption in the United States was served to customers at two high-end restaurants in San Francisco and Washington, D.C.

Cultivated meat is still far from your supermarket shelf. Chicken developed by two California companies is available in extremely limited quantities at only those two U.S. restaurants, where menu prices don't begin to reflect the astronomical costs of producing it. But more than 150 companies and hundreds more researchers worldwide, including Floreani and Tahir, are working to change that.

Proponents of cell-cultivated protein believe it could help feed the increasing population of a climate-changed world and meet a growing demand for meat in a more humane way, all without the environmental harm caused by industrial livestock agriculture.

Related Event: Learn About Lab-Grown Meat at the Vermont Tech Jam

Event: Learn About Lab-Grown Meat at the Vermont Tech Jam

Tech

When asked if replacing meat with beans might better serve the planet, Tahir agreed it would. But "that's not what people want to do," the 29-year-old doctoral candidate said. "You can wish for something, but after a certain point, you do have to kind of face reality and then come up with alternatives."

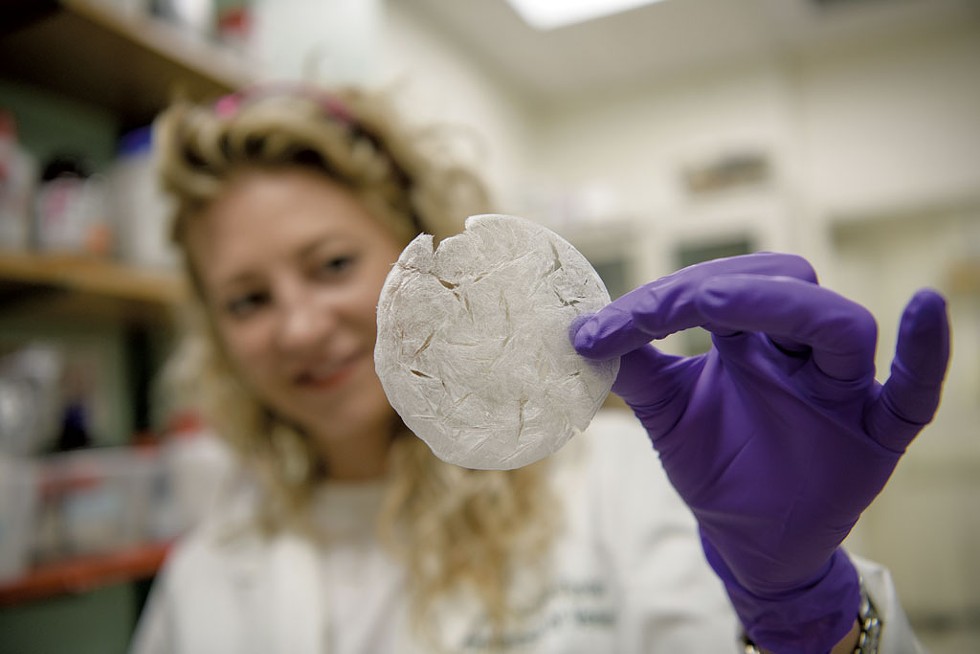

In the UVM biomaterials lab, shelves are stacked to the ceiling with plastic tubs holding bottles of chemicals. Every available surface is lined with high-tech machines. A boxy lyophilizer freeze-dries liquids into solids — "kind of like astronaut ice cream," Floreani said as she guided visitors on a tour. Another device agitates materials to ensure they can tolerate the jostling of the bioreactors in which meat cells will eventually be grown.

The UVM team is tackling a step in the production of lab-grown meat that could not only help develop whole muscle cuts but also make all kinds of cultivated meat "cheaper, faster and tastier," Floreani said.

A large metal canister in the lab hallway holds slender tubes in liquid nitrogen, each containing about a million cow muscle cells. It would take 50 to 100 billion meat cells to make a burger, Tahir said, pulling out a tube amid tendrils of vapor.

The lab devotes much of its work to developing materials for medical purposes, such as delivery mechanisms for targeted cancer drugs. But since late 2020, Tahir has been driving research in the field known as cellular agriculture.

"I get confused looks, like 'What do you mean that you make meat without animals?'" he said.

Floreani and Tahir are refining a material called scaffolding, which can help cultivated meat cells multiply from a mere million into the many billions that would be required to put something between hamburger buns.

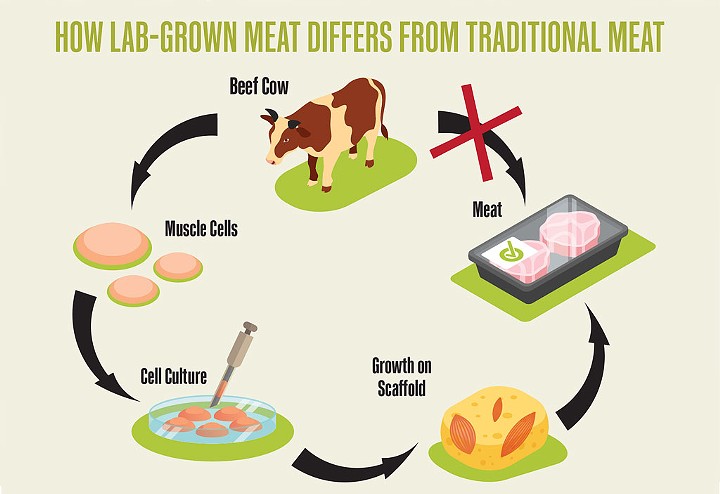

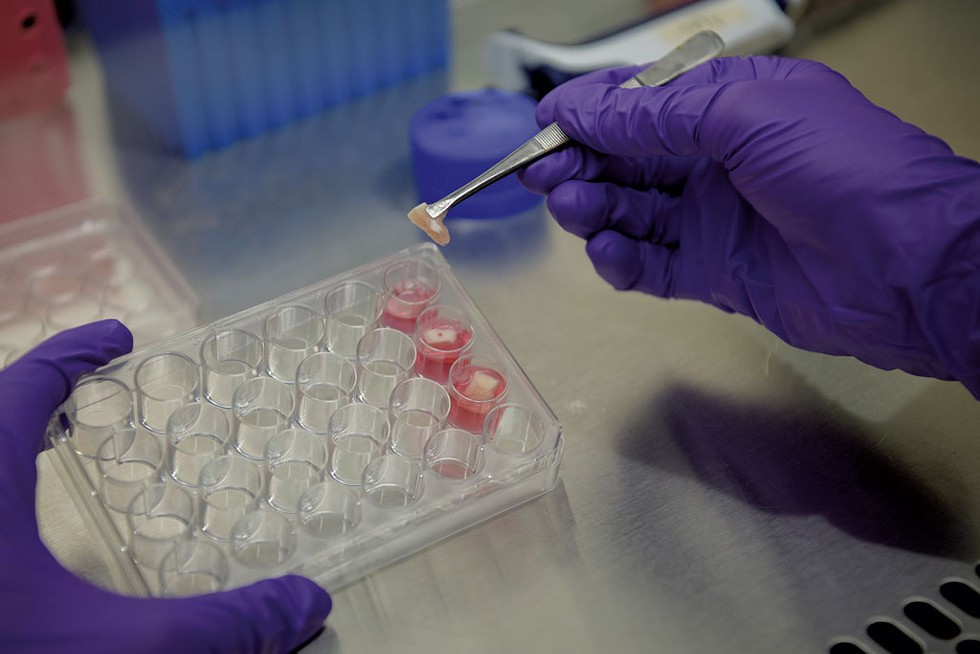

On a recent day, small white fragments of the scaffolding sat in petri dishes on a lab counter, resembling shards of communion or Necco wafers.

Over the past five years, companies all over the world working on cultivated meat have attracted more than $2.5 billion in capital investment, according to the Good Food Institute, a global nonprofit that promotes the production of nontraditional sources of protein. Many of those businesses are clustered in tech hot spots, such as California's Bay Area.

Floreani is entering the crowded pack with her own fledgling company, Burlington Bio, which seeks to turn the UVM lab's research on scaffolding material into a business.

It may seem incongruous to plant such an enterprise in Vermont, where pastures are dotted with the livestock of small-scale farms and agriculture is deeply entwined with the local sense of identity. Some might view the state as the antithesis of high-tech meat.

Floreani sees it differently.

"Vermont's known as a food state. We have agriculture ingrained in our society," she said. "If the world is going to move away from traditional agriculture, shouldn't Vermont be a part of that?"

John Abele, a Shelburne resident and cofounder of Boston Scientific, is one of Burlington Bio's early investors. He argues that the opportunity to explore technology to produce food in a way that could limit further environmental damage is too important for Vermont to pass up.

"This is a huge challenge for society," Abele said. "This is a problem we have to solve."

Not everyone agrees that lab-grown meat technology is a good way to ensure that the world's future children don't starve — or even that it can do so.

For one thing, the science is unproven on a large scale. Companies also need to convince a skeptical public that meat grown in huge steel tanks can be nutritious and tasty while delivering a demonstrable environmental advantage.

Some worry about who will control such potent technology and whether it might open a Pandora's box.

But those who see cultivated meat as a potential breakthrough argue that it is irresponsible not to use all the tools available to feed the world, whose population is projected to reach 9 billion by 2040.

Isha Datar runs a global nonprofit called New Harvest, which supports making all research in the field publicly available and awards fellowships to students, including Tahir. During a recent talk in Burlington, Datar acknowledged the many challenges that accompany growing meat in a lab.

"It has enormous power to change the world," she said, "but how it changes the world is up to us."

Meeting of Minds

Burlington Bio does not yet have a website or logo. The company has kept a low profile until this month. On the weekend of October 1, Floreani pulled stored laboratory equipment from among the toys and bikes in her Burlington garage and drove it to a new 800-square-foot office and lab space on Hula's South End campus.

Burlington Bio aims to perfect one particular version of the scaffold developed in the university biomaterials lab. Once it accomplishes that, it might license the scaffold protocol — instructions for creating it — to companies that produce cultivated meat, or it might manufacture the scaffolding in volume and sell that.

Floreani juggles the startup with her teaching and research duties, powered by at least eight cups of coffee daily. She said she would love to have Tahir join Burlington Bio after he graduates next June, but he wants to keep his career options open.

The Burlington Bio team of seven includes cofounder Cassidy Petit, a 26-year-old UVM alum with tech funding experience. So far, the company has two backers: Abele and Hula's venture capital fund. Floreani declined to say how much each has invested.

On Sunday, October 22, a standard 18 months after Floreani filed for the patent — her seventh — her application for the scaffold protocol will be published. This unveiling of sorts doesn't guarantee the patent will be granted, but it marks a milestone, as more researchers and companies make progress on different scaffolding approaches.

It was Tahir who proposed that Floreani's lab tackle cultivated meat, using materials she originally designed for the biomedical field.

click to enlarge

- Source: Rachael Floreani and Irfan Tahir

- How lab-grown meat differs from traditional meat

Tahir moved to Burlington in fall 2020 after earning his master's from the University of Minnesota Duluth. From his first encounter with the down-to-earth, effervescent Floreani, "I could tell we would vibe," Tahir said. He described Floreani as the rare professor who urges students to apply what she calls her material "toolbox" to their own interests rather than simply serving her research needs. In the lab and beyond, he said, "she encourages us to be ourselves."

Floreani, in turn, recalled being struck by Tahir's maturity, intellect and warmth.

But she is no soft touch. The first time Tahir made a research proposal, she shut it down quickly while helping him understand why. "It was a bad idea," he acknowledged.

A neatly bearded young man and avid soccer player, Tahir grew up in the Pakistani city of Rawalpindi in a family that prized education. His English teacher suggested he apply for an American exchange program. At 15, Tahir landed in a suburban Duluth high school, where a hands-on science class captivated him. A physics teacher challenged students to lie on a bed of sharp nails to understand how pressure, force and area combined to prevent the nails from puncturing their backs. "I was the first one to volunteer," Tahir said.

At college in Turkey, Tahir's mechanical engineering curriculum included biology. He also took several classes in philosophy, which inspired him to become vegetarian, then vegan. "I really could not find any justification whatsoever that in 2017 we should still be eating animals," he said. "They feel pain. They have emotions."

Similar ethical considerations motivated him to cut his environmental footprint. Later, one of his professors who had founded a cultivated-meat company encouraged Tahir to look into the field.

Tahir doesn't miss meat, but he harbors a fond childhood memory: KFC's spicy Zinger chicken. "One day I would like to eat that again," he said.

The scientific processes behind cultivated meat are not themselves new. Tahir likes to point out that cell cultivation led the way to an animal-free alternative to insulin, previously made from pig and cow pancreases. The field is also related to tissue engineering, such as growing human cells for skin grafts.

Pitching his idea to Floreani, Tahir proposed adapting a material that she had engineered from brown seaweed to support meat cells as they grew. He directed her to videos of factory-style farming of livestock, detailed its impact on the climate and explained how cultivated meat might increase food security.

It was not a hard sell.

"I have three children. The idea of a child starving just makes my hand go into a fist," Floreani said. "I'm not a farmer. I don't have land. What do I have? I have a lab, and I have an education. I can make food, too."

Floreani said her three daughters drive her to succeed. In her UVM office, a framed, Barbie-pink card from her 12-year-old is emblazoned "Boss Mom."

Her eldest was 3 months old when Floreani arrived at UVM in 2011 after completing postdoctoral work at the University of Washington in Seattle. There, her projects included materials to deliver vaccines to immune cells and tissue engineering aimed at building cultivated cartilage and bone for joint repair. Earlier, during her PhD work at Colorado State University, Floreani was a coinventor on an orthopedic implant that would land a patent.

Floreani knew no engineers or professors while growing up in rural Michigan, she recalled. Her parents, a mail carrier and a nurse's aide who later became a nurse, set high expectations, and she worked hard to earn a scholarship and became the first in her family to attend a four-year college. When a counselor suggested engineering, "I had no idea what engineering was," she said.

But Floreani chose to study biomedical engineering, inspired in part by a video her grandfather brought home of his knee surgery. She recalled thinking, "Whoa, that is so cool!"

It was not until her senior year that Floreani had her first female professor. "She was bubbly, fun and clearly very smart," Floreani recalled. "I didn't know that someone like me could be a professor."

Several women mentored Floreani along the way. In her current role as a tenured professor and business owner, she tries to do the same for other people, particularly those who identify as women or nonbinary.

"I really do feel like I need to be a role model and tell everyone you don't have to look and sound a certain way," said Floreani, who sports long, tousled blond hair and an armful of tattoos. "I do not look and sound like a mechanical engineer," she said, laughing.

She and Abele have lunch at least once a month, and he mentored her before investing in Burlington Bio. "We never talk about money," she said.

Abele said Floreani stands out for her "competent but humble attitude." Navigating a field as controversial as cultivated meat will call for "statesmanship capabilities, the objectivity to be open to alternatives," Abele said. "That's what Rachael has."

Culture Clash

Though Floreani is a scholar by training, she has come to see the private sector as the fastest way for her tool to reach companies that make meat to feed people. But, she added, "companies like secrets, and they like their patents."

With one foot in business and the other in academia, Floreani faces a tension between the attitudes of those two fields. The Burlington Bio scaffold is built from whey protein, a dairy processing by-product, along with the original seaweed. That detail will go public officially when her patent is published, but Floreani hesitated before revealing it to Seven Days ahead of time.

Tahir has also encountered some of those tensions. Over the summer, he interned with a San Francisco company working on a cultivated version of rich, Japanese-style Wagyu beef. He found the pace faster than in academia and the resources vast, but he was uncomfortable with the secrecy required.

The approach is very different at New Harvest, which awarded Tahir a three-year, $162,000 fellowship to fund his cultivated meat research at UVM. Since 2015, the nonprofit has supported 60 researchers at 37 universities in nine countries, requiring that all of their research be open to everyone. New Harvest funds individuals — not projects or labs — to ensure independence and flexibility in the evolving field.

UVM's scaffolding research may prove valuable, said Datar, New Harvest's executive director, but she described Tahir as an asset to the field regardless of the results of his current project.

The young researcher, Datar continued, founded a student cellular agriculture club and exceeded her expectations when she tasked him with coordinating a book chapter on the infrastructure of cultivated meat, working with researchers who were his seniors in the field. She gives Tahir credit for helping to secure an important donor for New Harvest. "He goes above and beyond the student role and is actually just an advocate for the field," she said.

One piece of evidence graces Tahir's white Subaru: a "CELL AG" license plate.

Fixing Food

Tahir, Floreani and Datar were among several hundred attendees last month at a semiannual gathering at Hula that aims to jump-start conversation on possible solutions to the world's thorniest problems, from pollution to inequality.

This time, the organizers of the event, known as the See Change Sessions, put food on the agenda.

A two-part workshop was devoted to "A Shared Vision for a Sustainable Food System." Despite that title, it laid bare the divisions between those working in cellular agriculture and others who favor regenerative agriculture — that is, a sustainable version of traditional farming, including livestock.

Datar argued for cellular agriculture's potential to protect against climate disasters and animal-to-human epidemics without gobbling up rainforest, guzzling water or belching methane into the atmosphere. She also acknowledged that, depending on who funds and deploys the technology, it could "extend industrialization of the food system, which we all agree sucks right now."

But Steve Schubart, rancher-owner of Grass Cattle Company in Charlotte, heard little at the conference to soften his skepticism toward cellular agriculture. Schubart raises grass-fed Angus and Wagyu beef cattle in a way that he believes restores the environment and produces food in a regenerative loop. He said he sees cultivated meat as simply a new type of processed food that is likely to be controlled by profit-driven corporations.

Aaron Carroll, who raised 1,500 meat birds on pasture this season and tends about 80 laying hens at Sowing Roots Farm in Underhill, expressed unease over what he called "the unintended consequences of good ideas."

Carroll said he thinks a lot about raising protein without hurting animals. "I've never thought more about becoming a vegetarian [than] since I've been a farmer of poultry," he said. He pointed to the darker side of agricultural technology, such as antibiotic overuse and monopoly control of equipment and seeds.

Samantha Langevin, a former chef, lives in Bristol and works for the nonprofit Vermont Releaf Collective, whose name stands for racial equity in land, environment, agriculture and food. She said ocean degradation is likely to soon drive demand for cultivated seafood.

"We need to try everything. That's the reality of the climate emergency," Langevin said.

Langevin said she was glad to hear some proponents of cellular agriculture say they hoped to replace only industrial livestock farming, not all animal farming. She observed that people of color tend to suffer the most from industrial agriculture practices because they are often the ones who work in huge slaughterhouses or live in areas where factory farms pollute air and water.

As the climate crisis intensifies, it will cause disproportionate harm to people of color living in some of the most vulnerable parts of the world, Langevin added. Cultivated animal proteins could help provide them with food through drought and other disasters. "We do need to diversify where food comes from," she said.

What's Your Beef?

People who aren't immediately concerned with survival may have a different first question about lab-grown meat — namely, "How does it taste?"

Reservations at restaurants serving cultivated chicken are as scarce as hen's teeth, and those who have snagged them say it tastes like, ahem, chicken. So far, though, most cultivated meat is an unstructured mass of cells that must be laboriously fashioned into familiar forms of meat or fish.

That's where Floreani and Tahir's scaffolding comes in. In broad terms, it substitutes for the skeleton and cartilage of the animal to provide a flexible structure around which cells could grow into something more closely resembling the packaged parts found in supermarket coolers.

The UVM team can't currently taste its test meat because the lab's medical research involves toxic chemicals, such as chemotherapy drugs. (A new graduate student who is a trained chef and works in a different lab will soon change that.)

When people talk about taste, though, they also mean texture. Scaffolds could help improve the texture of all cultivated products.

"We can trick ourselves into all sorts of taste," Floreani said. "If we're trying to get people to eat non-slaughtered burgers, texture matters."

But what produces a juicy, flavorful, chewy bite of steak goes beyond the genetic material in the cow's cells and into what it eats and how it moves. Furthermore, each cut is a complex blend of muscle and fat cells that transform when cooked, contributing to the aromas, flavors and textures that make meat taste like meat.

In short, bioreactor-grown cells have a long way to go to come close to a Grass Cattle steak or hamburger. If they ever do, Vermonters may ask if there's still an argument for local livestock farms.

On a recent morning in Charlotte, Grass Cattle's ranch manager, Ian Johnson, was moving about 35 pairs of cows and calves and a bull to a fresh paddock of the 161-acre farm, as he does at least once a day during grazing season.

The animals rushed to the newly available swath of lush fall grass. "It's always a race to find the best grass," Johnson said.

Advocates of cultivated meat point to data showing that livestock agriculture — especially cattle — accounts for up to 17 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions, from the methane the animals burp to the land and other resources used to grow their feed.

Schubart, Grass Cattle's owner, agrees with criticisms of industrial agriculture, but he rejects cultivated meat as the solution. To him, it looks like a two-headed monster: Big Ag meets Big Pharma.

Farmers who raise grazing animals exclusively on grass (fresh or dried as hay in the winter) argue that they are improving the ability of their soil to absorb carbon and hold water, thus creating a healthier environment for all creatures. In his fields, Schubart pointed to the abundant webs of orb weaver spiders as "a great sign of soil health."

Critics say farms like his can't feed enough people, but Schubart believes there is opportunity for more small-scale farmers to pursue similar practices both here and abroad. He supports global programs that supply livestock and agricultural training to those in need of food. "It puts the power in their hands," he said.

In Schubart's view, more resources should go toward cutting the mountains of food waste and building infrastructure in the developing world to manage the food we have, rather than spending billions to fund cellular agriculture.

"It's a big tech-bro distraction," he said.

Long Odds

Although Tahir is at least partly motivated by a belief that humans should avoid eating other animals, the case for cultivated meat does not typically target the small percentage of people who have given up meat out of concern for animals or the environment. Many vegetarians and vegans say they would disdain eating the flesh of animals grown in labs, too.

In any case, the field of cultivated meat cannot claim to be slaughter-free until it replaces a fetal bovine serum that is widely used to help meat cells grow. Long part of biomedical cell cultivation, the serum comes from fetuses removed from slaughtered cows. Researchers and companies have made progress on several alternatives.

Burlington Bio faces a related ethical conundrum regarding the whey protein used in its scaffolding. Floreani is pleased to have found a use for whey, which is a by-product of dairy processing and a potential environmental pollutant. But she recognizes that it comes from livestock farming, she said, and hopes soon to find substitutes for both fetal bovine serum and whey.

In the meantime, cultivated meat producers focus on wooing the world's billions of current and future meat eaters based largely on climate arguments. They hold out the promise of preparing for a Soylent Green-style future in which the world's population exceeds its capacity for producing meat any other way.

Whether those companies can leap the scientific and cultural hurdles — and whether a pair of UVM researchers and the tiny new Burlington Bio can play a role — are bets with very long odds.

Last month, Wired magazine published an investigation into UPSIDE Foods, the $1 billion California startup making the chicken served in San Francisco. Reporters found that the meat the company produced from cells was limited to minuscule batches that were handcrafted, rather than produced through the large-scale methods needed to make the product commercially viable and meet its investors' expectations.

Meanwhile, Brazil-based JBS, the world's largest beef producer, announced recently that it was investing $62 million in a cell-cultivated meat research facility. The New York Times reported that, to fuel its growth, JBS is pursuing a listing on the New York Stock Exchange. Environmental organizations are trying to block that move, citing what the paper described as JBS' "shoddy environmental record and a litany of dubious corporate governance practices."

Next to supersize players such as these, Floreani and Tahir represent but a few meat cells in a 50 billion-cell hamburger.

Yet Abele, the investor, said focusing solely on the success of Burlington Bio's scaffolding approach might miss a larger point.

"This is maybe a small, little piece," he said, "but it's also symbolic of really taking on a very difficult problem and understanding how food works from a much more basic level."

Seven Days deputy publisher Cathy Resmer will host a conversation with Rachael Floreani and Irfan Tahir about lab-grown meat during the keynote presentation at the Vermont Tech Jam on Saturday, October 21, 3 p.m., at Hula in Burlington. Talk with other local tech companies at the Jam from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. To attend the free event, register at techjamvt.com.

The original print version of this article was headlined "High Steaks | Lab-grown meat could help feed a climate-changed world. Newly launched Burlington Bio hopes to take a bite."

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

About The Author

Melissa Pasanen

Bio:

Melissa Pasanen is a food writer for Seven Days. She is an award-winning cookbook author and journalist who has covered food and agriculture in Vermont for 20 years.

Melissa Pasanen is a food writer for Seven Days. She is an award-winning cookbook author and journalist who has covered food and agriculture in Vermont for 20 years.

More By This Author

Latest in Category

Speaking of...

-

Couple Killed in California Plane Crash Had Ties to Burlington's Tech Scene

Jan 19, 2024 -

Video: Dr. Rachael Floreani & Irfan Tahir Discuss the Future of Lab-Grown Meat

Dec 7, 2023 -

Seven Vermont Tech Startups Worth Watching

Oct 18, 2023 -

Bird, a ‘Dockless’ Bike-Share Program, Has Landed in the Burlington Area

Oct 18, 2023 -

UVM Philosophy Professor Randall Harp on the Moral Dilemmas of AI

Oct 18, 2023 - More »

find, follow, fan us: