click to enlarge

- Sally Pollak

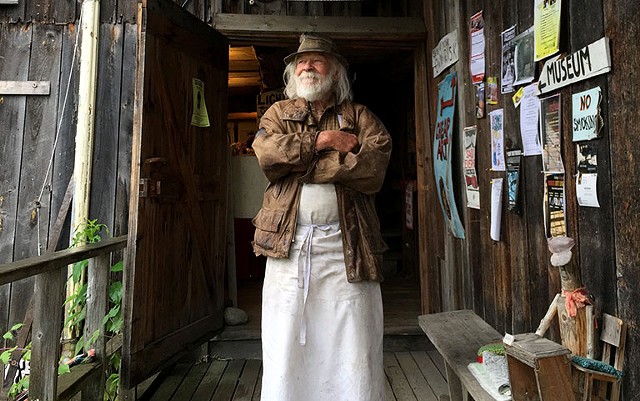

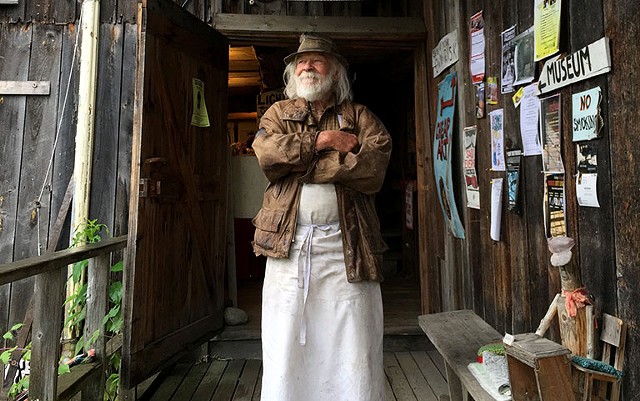

- Peter Schumann at the entrance to the Bread and Puppet museum

The visitors have thinned out at the Bread and Puppet museum-in-a-barn in Glover, and the grass amphitheater is empty. Four pails of flowers, the blooms dry and faded at summer's end, stand sentinel on the counter of the Bread House. Its shelves, all but bare, hold a bird's nest with a sole feather inside.

At his nearby farmhouse, Peter Schumann is baking bread. Schumann, who founded Bread and Puppet Theater 54 years ago, works alone in his open-air baking shed while this reporter watches. A steady rain drums on the metal roof. From a big stainless-steel bowl, he scoops a hunk of rye dough, kneads it and shapes it into a loaf. He repeats the process again and again, as if working in time to the falling water.

"That's the sound system that we call rain," says Schumann, 83. "It's a very nice sound system."

Aprons, garden clippers and a hacksaw hang from a beam. Bathtubs by the bread oven hold mud for making puppets. A laminated poster with Schumann's artwork lies on the wet ground, having fallen from the woodpile. Its words and image — stalks of grain bent in the wind — speak to his life's work: "We give you a piece of bread with the puppet show because our bread and theater belong together."

Schumann has been baking sourdough rye bread for 77 years, since his childhood in Germany. He made it as a little boy with his mother and as a 10-year-old refugee of the war.

"Bread was a thing the family took seriously," Schumann says. "It was the most desired object, to have enough for family and friends."

The bread is made with rye flour, salt and water — and, lately, rye berries — to form a coarse and crusty loaf that requires effort to eat.

"It's a thing that reveals itself only when you work at it," Schumann says. "When your teeth do their job."

In 1963, when Schumann founded his theater in New York City, the joining of bread and puppet was both obvious and necessary, he says.

"The two of them had to be married; they were very much engaged," he explains. "We fed bread to the public so they were chewing when they were watching the show. We thought they were a better audience."

click to enlarge

- Sally Pollak

- Peter Schumann baking rye bread

If Schumann's bread takes work to digest, the same might be said of his theater: "It's not so good for the lazy mind who wants to be tickled or entertained," he says. "Probably not so interesting."Schumann and his family moved to Plainfield in 1970, when he accepted an invitation to be a theater resident at Goddard College. He ran Bread and Puppet there for four years before moving with his wife, Elka, and their five children to a former dairy farm in Glover."Slowly and surely, the theater came," Schumann says, adding that his kids "were all puppeteers 'til it came out of their mouths."

Bread and Puppet grew into an influential and innovative theater company — making spectacular, larger-than-life papier-mâché puppets; touting "cheap art"; and performing its brand of good-humored yet politically acute puppet theater in the Northeast Kingdom and beyond. At the annual Domestic Resurrection Circus, which drew big summer crowds to Glover through 1998, puppeteers sang and danced — and gave away rye bread with garlic-parsley aioli to thousands upon thousands of people.

"We baked relentlessly," Schumann says. "We baked and baked and baked."

A photograph of him baking bread, recently posted on Facebook, elicited comments such as "food for the soul" and "keep my heart full even when my spirits sour." A local musician remembered it as the first free bread he ever ate. Hotel Vermont chef Doug Paine remembered attending Bread and Puppet shows as a young teen. Schumann's rye bread and aioli is one of his "early great food memories," Paine wrote. He called it a "Vermont treasure."

After shaping his loaves, Schumann places them on a board and loads them into an oven he made from river mud — the same mud the company uses to make molds for the puppets. When 30 or so loaves are in the oven (Schumann doesn't count them or measure temperature), he drapes a wet towel over the door to seal in the heat.Schumann then dons a battered leather jacket over his apron, steps into the rain and leads his visitor into a common room at the farmhouse. The large, sparsely furnished space holds two pianos and a mill for grinding his farm-grown rye into flour.

click to enlarge

- Sally Pollak

- The woodpile

On a post in the middle of the room hangs a calendar that Schumann made, its pages open to September 2017. The date of the full moon is marked, and so is Yom Kippur. Blocky, black letters printed across the calendar form the word "BACKWARD." Sitting in a chair by his calendar, Schumann looks back on his bread.

He was a boy of 6 when he started helping his mother, Margarethe Schumann, bake sourdough rye — the "common people's bread," he says. White bread was reserved for special occasions and eaten like cake, he notes. Schumann and his four siblings lived with their parents in the Silesia region of Germany (now Poland) in the town of Breslau. His father, Hans Schumann, taught literature and history and wrote texts on "pedagogical problem-solving." He was interested in radical, modern school systems, Schumann explains.

In 1944, when Schumann was 10, his family fled their hometown to escape Allied bombing and Russian tanks. Each child was allowed to bring a bag on the journey to a village by the Danish border. Schumann packed his with wooden-headed hand puppets, he says.

About 100 refugees lived in the village. They gleaned grain from fields planted in rye, barley and wheat. Hedgerows protected the crops from the wind, he remembers. Schumann and his siblings threshed rye and ground it in a coffee mill. Families kneaded dough and shaped it into loaves at their homes.

click to enlarge

- Sally Pollak

- Outside the Bread and Puppet bakery

Once a week, they carried their loaves on a board to a communal oven for baking. Each family marked its bread with an imprint, an identifying symbol, to distinguish their loaves from the others'. Trees were too valuable to burn in the bread oven, so wood cuttings from the hedgerows fueled the fire. The Schumanns would spread their bread with jam made from elderberries and rose hips that the children picked from the roadside.

"Especially for those of us who were war victims, everything had to be made for yourself," Schumann says. "We lived there on the farm as refugees, gleaning the fields and working on the farms."

A regiment of German soldiers lived in the village, too. When Schumann was 11, he and his younger brother, Michael, went to the soldiers' tents with their hand puppets and made a puppet show for the men. It was his first public performance. He had basic puppet characters — a princess, a robber, a cop and a ghost — but no bread to give away.

"The bread was too precious," Schumann says.

Decades later, after he had moved to New York City with his American wife and their two oldest children, Schumann thought people were deprived because the white or wheat bread they ate was of inferior quality.

"In the glass palaces of New York City," he says, "they didn't know what bread was."

click to enlarge

- Sally Pollak

- Outide the Bread and Puppet bakery

Bread and Puppet will present one more show in Glover this season, "Political Leaf-Peeping," on Sunday, September 24. Schumann says he'll continue to make puppet shows for as long as he can.

"They might make it illegal," he warns, referring to the current administration. "It might become illegal to do puppet shows, based on what's happening in the United States as it becomes more fascist."

Schumann will also, of course, continue to bake bread and give it away. Maintaining that practice over a lifetime "feels very good," he says.

"You still have to improve it," Schumann advises. "There's still stuff that you're fussing with, always to improve it. It's continuously changing. It's never quite done."

Although Schumann's rye bread belongs to everyone and to no one, he still marks each loaf before baking it. He uses a tin stencil made by a friend and shaped like the shining sun.