Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

-

Education

Scott Official Pushes Back on Former State…

-

News

Burlington Budget Deficit Balloons to $13.1 Million

-

Education

Senate Committee Votes 3-2 to Recommend Saunders…

- Court Rejects Roxbury's Request to Block School Budget Vote Education 0

- Norwich University Names New President Education 0

- Media Note: Mitch Wertlieb Named Host of 'Vermont This Week' Health Care 0

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

In the Studio With Windham Hill Founder Will Ackerman

Published April 2, 2014 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated October 8, 2020 at 5:39 p.m.

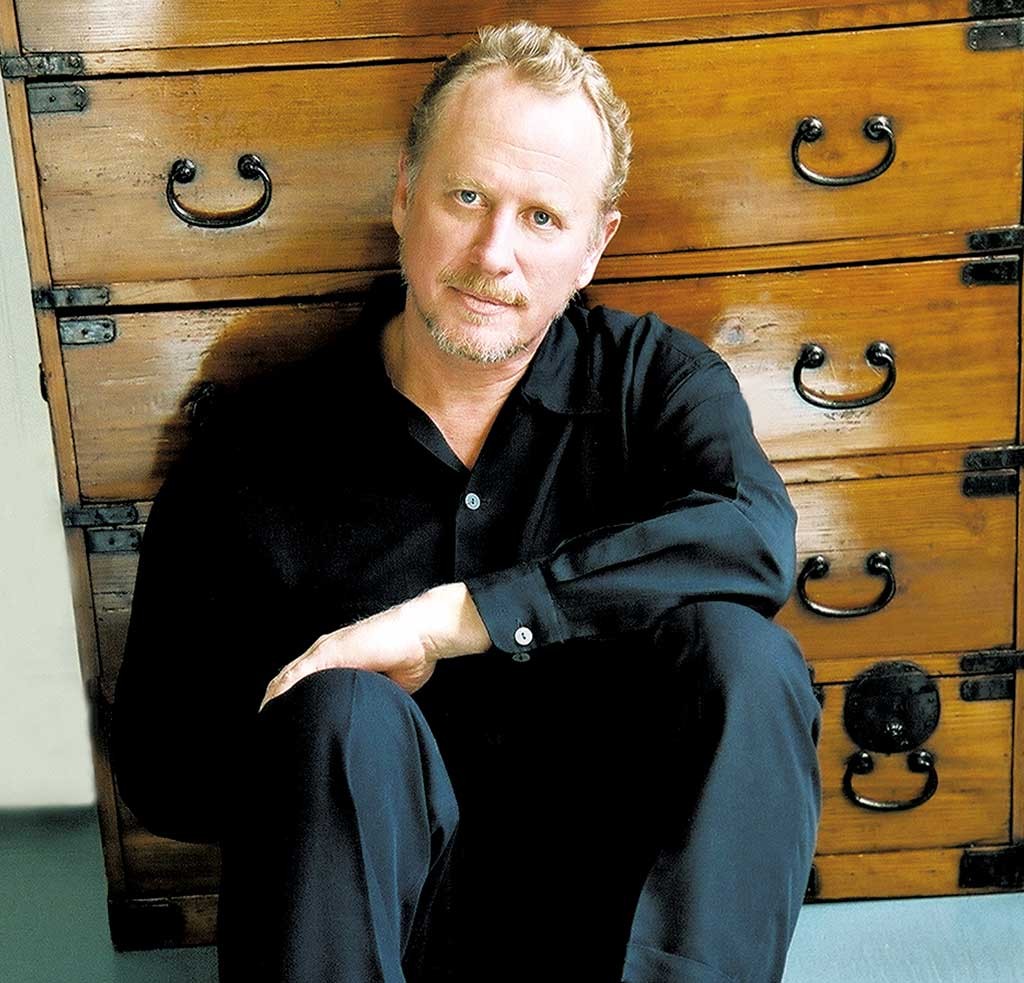

Peter Jennison is having a hell of a time. Seated at the Steinway Model B grand piano of producer Will Ackerman's Imaginary Road Studios in Dummerston, Vt., the pianist is struggling to play a particularly tricky section of a song he's recording for his new album.

Ackerman and his recording engineer, Tom Eaton, sit at the helm of the large mixing board on the other side of the studio glass, listening with grim focus as Jennison grinds through take after take. After each attempt, Jennison, a quiet but imposing man whose black mock turtleneck does little to diminish his barrel chest, bows his head in a mixture of solemn concentration and growing frustration.

"He's not gonna get this one today," says Ackerman, clad in a black turtleneck of his own. Eaton nods in agreement, tweaking a slider on the board. Eaton is not wearing a turtleneck, but his black sweater with a three-quarter zip-up neck is close enough for jazz. Or, in this case, new age.

It's the right-hand part of the song's hook that's giving Jennison trouble. The section contains a rippling piano run that bears a striking resemblance to the 1986 Bruce Hornsby hit "The Way It Is" — so much so that the three men casually refer to the tune as "the Hornsby song." It's a nifty little arpeggio, but every time it comes around, Jennison's otherwise nimble fingers stumble. He loses the rhythm, and the whole thing derails. Every time, almost on cue, Ackerman and Eaton exchange furtive glances.

After the seventh or eighth — 10th? 12th? — such instance, Ackerman turns to Eaton.

"You know, Bruce Hornsby is a great basketball player," he says, his face tanned from a recent surfing vacation in Hawaii. "You always wanted him on your team in pickup games," he continues, as errant notes tumble from the monitor speakers. "Otherwise, he was gonna reverse dunk on you."

That would be a newcomer's tip-off that Ackerman is a gazillion-records-selling, Grammy-winning guitarist and producer. He is most famous as the founder of Windham Hill Records, an influential label that has become globally synonymous with "new age" music — a term Ackerman openly despises. The foyer of Imaginary Road — named whimsically but perhaps also for the steep, negligible mountain road one must navigate to reach it — is lined with gold and platinum records from projects Ackerman has produced in his 40-plus-year career. Those include his own and several by Windham's Hill's one-time star artist, pianist George Winston.

With the possible exception of guitarist Michael Hedges, Winston is the best known of the new age ... er, contemporary instrumental musicians with whom Ackerman is associated. But Ackerman has produced records for many of the world's most respected artists in that wide, gently rolling field. His clients have ranged from genre heavyweights such as Jeff Oster, Liz Story, Philip Aaberg and Ackerman's own cousin, Alex de Grassi, to up-and-coming players including Jennison, Heidi Anne Breyer and Rutland's Masako. And Ackerman has a knack for identifying prodigiously talented unknowns, most recently Vergennes-based 17-year-old guitar wunderkind Matteo Palmer.

Outside the instrumental sphere, Ackerman has spearheaded records for, among many others, folk singer Patty Larkin and songwriter John Gorka. He's composed for pop star Kenny Loggins. After Ackerman sold Windham Hill to mega-label BMG in 1992, a noncompete clause prevented him from releasing music for three years. So he produced spoken-word records under the label Gang of Seven. These included albums for the late Spalding Gray and Ackerman's Windham County neighbor, humorist Tom Bodett — you can almost see Bodett's house from the floor-to-ceiling windows of the studio overlooking the picturesque West River valley.

With apologies to Dos Equis beer and Vermont's own Jonathan Goldsmith, there's a distinct possibility that Ackerman is the real "most interesting man in the world." He gets invites to resorts in the Caribbean hosting shoots for the Sports Illustrated swimsuit issue. He's tight with Japan's royal family. He didn't merely build his mountaintop studio and surrounding compound in southern Vermont by hand; he cut down the trees on the wooded lot and milled the lumber. In a dramatic pseudo-heist, he practically stole the piano that resides in his studio — which is now famous in its own right — from filmmaker George Lucas' Skywalker Ranch. The Force is strong with Ackerman (though he did end up paying for the instrument). He rocks black turtlenecks with impunity. He posts up Bruce Hornsby.

But today, Ackerman is simply trying to coax a good take from a talented, visibly frustrated musician. And he'll tell you there's nowhere in the world he'd rather be.

A Battle of Will's

On September 11, 2013, Ackerman lay on an operating table awaiting general anesthesia in preparation for minor heart surgery.

"It was very unlikely that I could die on the table," he says, now speaking by phone from his Dummerston home (and perfectly healthy). "But it occurred to me that it was a possibility. It does happen."

Confronted with his own mortality, Ackerman says, he began to reflect. What he discovered surprised him.

"I always thought I'd be afraid of death," he says. "But I was lying there, before the stuff was in me, feeling wave after wave of gratitude as all of these memories washed over me. And I realized that I wouldn't have changed a single thing in my life."

Given Ackerman's achievements, that's hardly a surprise. This is a man who has followed his passions and become wildly successful. It would appear he's led a charmed life — and in many respects he has. But, just as Ackerman's tranquil music can turn complex and moody below the surface, his own story has a darker subtext.

Ackerman was born in Palo Alto, Calif., in 1949. He was immediately given up for adoption by his biological mother, who had been exiled by her wealthy father to have her out-of-wedlock child alone. Baby Will had a seemingly fortunate outcome for an unwanted child: He was adopted by Robert Ackerman, head of the Stanford University English department. But his adoptive mother, Mary Ackerman, suffered from bipolar disorder. The day she hanged herself in the shower of their home, 12-year-old Will found her.

Within six months, Ackerman recounts, he was shipped off to prep school in Massachusetts. While his father indulged a new love interest 3,300 miles away, Ackerman fell prey to a pedophile. He would endure years of abuse.

Following high school, Ackerman began to emerge from the shadows of his tortured childhood. He returned to California and attended Stanford, where he studied writing and history.

"I always thought I was going to be a writer," says Ackerman. "It was always assumed I would end up in academia."

But a strange thing happened to Ackerman during his senior year. "I just ran out of words," he says. "I couldn't write a thing."

Ackerman took writer's block as a sign; with a mere five credits to go before graduation, he dropped out of school. He landed a minimum-wage job as an apprentice builder thanks to a connection through the father of his then-girlfriend, Suzanne. Ackerman would later immortalize her on his 1976 debut record, In Search of the Turtle's Navel, in the song "What the Buzzard Told Suzanne."

Soon, Ackerman started his own contracting company, Windham Hill Builders. Meanwhile, he performed and recorded music, both as a solo acoustic guitarist and with his cousin, de Grassi. By day he built lavish homes in northern California. At night he made records and ran his label. His dual reputations as a carpenter and musician were growing in equal measures.

"My business card in 1980 read Windham Hill Builders / Records / Music BMI," says Ackerman. "Which, I dare say, is the first time that's ever happened."

Ackerman's first paying gig was a sold-out show at the Seattle Opera House in the late 1970s. His first three albums, In Search of the Turtle's Navel, It Takes a Year (1977) and Childhood and Memory (1979), were commercial successes. By 1980, Ackerman was an established, bankable musician and producer. Windham Hill had national distribution, and its releases got heavy radio airplay on progressive stations around the country. And Ackerman was forced to choose between music and carpentry.

"It had gotten to a point where I had to decide if I was really going to do this music thing," he says. A spectacular and expensive screw-up on a client's home — he removed the roof prior to a freak rainstorm — helped him make his decision.

"I figured I might as well see where music would take me," Ackerman recalls.

That's when George Winston happened.

Windham Hill Records' early profitability would seem like a pittance once the world got a load of Winston and his 1980 Windham Hill debut, Autumn. Amazingly, Ackerman's distributors initially balked at the album. Most of the previous 11 Windham Hill releases had been guitar based, and Winston's dreamy piano compositions were a distinct departure.

"They told me I was going to wreck a nice little folk label," Ackerman recalls. "I told them, 'I don't have a folk label. I don't know what it is, but it isn't folk.'"

Autumn would be the label's best-selling album to date. Winston's follow-up efforts in 1982, Winter Into Spring and December, both went platinum.

"George blew the doors off," Ackerman says.

Ackerman signed an international distribution deal with A&M Records shortly thereafter. For the next decade, he says, the slowest annual growth rate for Windham Hill was "exactly 597 percent." The label's best years saw growth rates of 2,000 percent. Ackerman was a rock star, and he lived like one.

He owned a mansion and drove fancy cars. He dated a string of beautiful women. He traveled the globe performing and schmoozing. He was making more money than he could ever spend. But something was wrong.

In 1984, Ackerman began feeling ill. He saw doctors all over the world, but none could figure out what was ailing him. Finally, a psychiatrist diagnosed him with depression.

"I said, 'What do you mean, I'm depressed?'" recalls Ackerman. "'I'm on top of the world. I drive a Mercedes. I've got a really nice house. Look at my girlfriend!'

"He said, 'Dude, you're depressed.'"

Ackerman realized he had never fully dealt with his mother's suicide, or the abuse that followed. Despite his fairy-tale success, he was a haunted man. "I had just packed it all away," he says.

Ackerman began to view Windham Hill with apathy, if not outright contempt.

"I was bored," he says. "It became a corporation. We had 70-some employees and big offices in Burbank, which I went to once, I think. I got lost in it all, and the guy who used to sit around playing guitar wasn't there anymore. It was just killing me.

"I just wanted to be a carpenter again," he continues. "I missed sitting on the tailgate having a couple of beers at 5:30."

So Ackerman quit.

"I said, 'Screw it,'" he recalls. "'I'm going to Vermont, I'm gonna buy some land, get a chainsaw and build again.'"

Ackerman incrimentally sold his stake in Windham Hill and was completely free of the company and various holdings by 1992. By that time, he had constructed Imaginary Road and was living full time in Vermont.

"It was my salvation," he says.

A New Age

There's an irony in Ackerman finding peace by fleeing Windham Hill Records; millions have flocked to the calming sounds of the paragon of so-called "new age" music seeking the same. The Windham Hill canon is the soundtrack to new-age bookstores and therapy sessions the world over. Ackerman is aware — you might say painfully so — of these associations. And he's an advocate for therapy, having seen therapists for most of his adult life — though he refers to them as teachers. Still, he has little use for that gooey catchall phrase.

"I hated the term until they gave me a Grammy that said 'new age' on it," he jokes, referring to his award-winning 2004 record Returning. "But my official quote, which was in the Los Angeles Times several years ago, is that if I ever catch the guy that coined the term, I'm going to nail his forehead to the wall. Is that too ambiguous?" he asks.

Stephen Hill is the creator and host of "Hearts of Space," a decades-old, nationally syndicated radio program that specializes in "slow music for fast times" — meaning ambient, world, classical and, yes, new-age music. He shares Ackerman's disdain for the term, but offers context. "New age," Hill explains, was created in the 1980s as a label for record-store bins full of instrumental music that was not jazz, folk or classical.

"It should have been called 'new instrumental,' which would have saved a lot of heartache and confusion all around," Hill writes in a recent email. "Instead, we got this grandiose, pseudo-spiritual moniker, no filters and way too much well-intentioned but lousy music."

"There is so much lifestyle that is tacked onto that term," Ackerman says. "Windham Hill was never about a belief system. We weren't selling anything but music."

Hill concurs.

"Windham Hill really didn't care about new-age culture," he writes. "Will Ackerman took off from American folk guitar and created a sophisticated fusion of acoustic minimalism, state-of-the-art recording technique and contemplative space to make albums that were calm, hypnotic and American as cherry pie."

"Windham Hill worked because it was treated like a hobby," says Ackerman. "There was a purity in that everything we did was based on what we liked. There was no method; nothing was calculated."

Ackerman views his work at Imaginary Road with Eaton — whom he calls the "best partner I could ever ask for" — as a return to that nonphilosophy. He still works with many of the stars of contemporary instrumental music. The signatures of each, close to 100 in all, are scribbled on a door to the piano room. But Ackerman's focus now is more humble and personal.

"It's a return to a world that has human scale," he says. "Yeah, we want to work with great musicians, but we really want to work with people we enjoy being around."

Last year, Ackerman and Eaton produced Matteo Palmer's debut record, Out of Nothing. Then a junior at Vergennes Union High School, Palmer had approached Ackerman about performing at a benefit concert. Ackerman played with the young guitarist at the Vergennes Opera House and was blown away. He called the teenager about making a record the next day.

"The kid has an almost frightening ability to find the emotion in his music," Ackerman says. "It's not enough just to be a great player or composer, which he is. You have to play with passion, spirit, or else all that skill means exactly shit. And Matteo does."

Like countless musicians before him, Palmer credits Ackerman with helping him to divine, well, the divine.

"Will goes beyond just playing notes to find the real emotion in his music," says Palmer by phone. "That's what I love about his playing, and that's what he would tell me to do — dig deep."

Guitarist Todd Boston, who recorded his chart-topping 2012 record Touched by the Sun with Ackerman, offers similar praise in an email. "He hears the emotion in the music and knows how to get the very best out of you as the artist," he writes. "If there is not an emotional connection there, he will keep pushing until he gets something out of you that is soulful and heartfelt."

"Will is a great listener," says pianist Winston by phone. "When you're looking at a picture of yourself, you only see yourself in two dimensions. Listening, we hear ourselves, but it's kind of the same thing; it's distorted by our own limited perception. I hope it's good, but I don't really know.

"I think Will hears three-dimensionally," Winston continues. "So he is great at identifying when something is or isn't working."

Rutland-based pianist Masako, who has recorded two albums at Imaginary Road, says Ackerman has a strong "sense of aesthetic."

"He has the ability to discern in an instant the best artistic quality a musician has," she writes in an email. "That's not an easy thing to do when one is a great musician himself. But Will is a rare exception."

As a guitarist, Ackerman is well known for rarely using the same tuning for more than one song. In the entirety of his recorded output, 12 solo records in all, he says he has done so exactly twice.

"I go into a different tuning on every song so that I don't have the capacity to use intellect," Ackerman explains, and adds that he is essentially music-theory illiterate. "It removes the frontal lobes entirely from the process. It then becomes solely a way to channel emotion."

That approach also characterizes his nonmethodical endeavors as a producer. In the studio, Ackerman reacts instinctively, offering suggestions or criticisms with the ruthless speed of a gunslinger. And he's usually dead-on.

"He makes decisions quickly and confidently, often surprising the composer by the magic that results," writes Kathryn Kaye in an email. The pianist, who has recorded four albums with Ackerman since 2010, admits she's frequently surprised by his insights. "In my experience, he's right 99 percent of the time."

Of Mecca and Michael McDonald

Though Ackerman rejects the psychobabble often associated with new age, he is a deeply spiritual and contemplative person, keenly aware of music's healing power. After all, the proof of its therapeutic qualities is currently standing over his Steinway B, all six and a half feet of him.

Cpt. Peter Jennison is an active-duty medevac pilot in the United States Army. He's played piano since he was a child, never seriously and without classical training. Yet, while deployed in Iraq in 2008, he began writing an album of piano compositions.

"I was using music to get through the stress of war," says the soft-spoken Jennison, who'd been using a 1998 Ackerman album, Sound of Wind Driven Rain, to help him fall asleep. One day he noticed a line on the CD's back cover encouraging listeners to email Ackerman.

"I emailed him and said, 'Hey, I've got this idea for an album.' Then I went to lunch," says Jennison. "I never thought I'd hear from him."

When Jennison returned from lunch, he found an email inviting him to come record at Ackerman's Vermont studio. In 2009, Jennison released his debut, Longing for Home (Songs From War). "It's all about what we as soldiers, and our families, go through during long times apart," he explains.

The album garnered several award nominations and put Jennison on the map. The record he is currently working on is a sequel of sorts called Coming Home.

"It's about the reunions you see on TV, where the soldier comes out of the stands at a game and surprises his family," he says. "But on the other side are the soldiers who don't come home, the ones that come home in a box."

Jennison brings his raw sketches to the studio and relies on Ackerman and Eaton to tweak song structures, or bring in other musicians to flesh out arrangements. The mere act of writing and recording is therapeutic for him, Jennison says. "Music has become my coping mechanism for life."

That's a sentiment to which Ackerman can relate.

"I've been through some shit. And I've learned that there's no way to tease the bad from the good," he says. "There's only life, and without the terrible things that have happened, I wouldn't have the wonderful ones, either." Speaking of the music he makes at Imaginary Road, he adds, "Even despite the indignities of aging, this really is the happiest period of my life."

"It's called Imaginary Road, but think about that," says Jennison. "It's a place that doesn't exist, but music comes. It's the magical Mecca of music. And we all come here because it's sacred. But the foundation of that sacredness is that man sitting over there, Will."

Later, during a break in his increasingly tense session, Jennison goofs off by imitating vocalist Michael McDonald of Steely Dan and Doobie Brothers renown.

"That's what a fool belieeeeeeeeves!" he howls in a reasonable, if cartoonish, approximation of McDonald's brassy baritone.

Ackerman chuckles and leans into a microphone connected to the piano room.

"Peter, I've been onstage with Michael McDonald," he says with a grin. "You, sir, are no Michael McDonald. Play the piano."

Jennison smiles and goes back to work on that pesky run.

The original print version of this article was headlined "King of the Hill"

Related Stories

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

Tags: Music Feature, Peter Jennison, Will Ackerman, Imaginary Road Studios, Tom Eaton, Windham Hill Records, George Winston, Hearts of Space, Matteo Palmer, Todd Boston, Masako, Kathryn Kaye, Video

More By This Author

About The Author

Dan Bolles

Bio:

Dan Bolles is Seven Days' assistant arts editor and also edits What's Good, the annual city guide to Burlington. He has received numerous state, regional and national awards for his coverage of the arts, music, sports and culture. He loves dogs, dark beer and the Boston Red Sox.

Dan Bolles is Seven Days' assistant arts editor and also edits What's Good, the annual city guide to Burlington. He has received numerous state, regional and national awards for his coverage of the arts, music, sports and culture. He loves dogs, dark beer and the Boston Red Sox.

Speaking of...

-

Album Review: Matteo Palmer, 'Opaline Sky'

Mar 28, 2018 -

Imperfect 10: Recapping the Best Local Recordings of 2016

Dec 28, 2016 -

Presenting the 2016 Seven Dandelions

Aug 3, 2016 -

Soundbites: The Best VT Albums of 2016 … So Far (Part Two)

Jul 6, 2016 -

Matteo Palmer, Embers

Jun 22, 2016 - More »

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.

- 1. Soundbites: Burlington Record Plant On the Move Music News + Views

- 2. Three Quick-Hit Reviews of Local Albums Album Review

- 3. On the Beat: New Music From Phish and a Family Folk Affair in Grafton Music News + Views

- 4. Soundbites: Umphrey's McGee Loves Burlington Music News + Views

- 5. Community Garden, 'Me vs Me' Album Review

- 6. Six Quick-Hit Reviews of Local Albums Album Review

- 7. Frankie White, 'brain dead' Album Review

- 1. Soundbites: Trouble & Together at the Flynn Music News + Views

- 2. Soundbites: Burlington Record Plant On the Move Music News + Views