Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

-

Education

Scott Official Pushes Back on Former State…

-

News

Burlington Budget Deficit Balloons to $13.1 Million

-

Education

Senate Committee Votes 3-2 to Recommend Saunders…

- Court Rejects Roxbury's Request to Block School Budget Vote Education 0

- Norwich University Names New President Education 0

- Media Note: Mitch Wertlieb Named Host of 'Vermont This Week' Health Care 0

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

Oil & Water: A Racecar Driver and a "Genius" Inventor Vie for Lieutenant Governor

Published October 29, 2014 at 10:00 a.m.

Phil Scott leaned against his gleaming green racecar, somehow looking natural in a charcoal-colored jumpsuit. Barely audible over the sounds of motors revving, Vermont's soft-spoken lieutenant governor was making his third comparison between racing cars and running the Senate. He chuckled, conscious that his remark might come off as kind of cheesy, but was unable to stop himself.

"Racecar drivers are a lot like politicians. Quite a few of them have a fairly big ego," Scott explained. But Vermont's only Republican in statewide office is quick to point out that he's not your typical driver — or politician. "Some people think they have to win on every subject and every debate, and I look for ways for other people to win."

One person he's hoping won't win is Progressive Dean Corren, his challenger in the race for the state's No. 2 job. On that early October weekend, Corren had the courage to campaign on Scott's turf — Barre's Thunder Road racetrack. The reedy figure stood at the top of the amphitheater with a lawn sign at his feet and a Corren sticker affixed to the bill of his red baseball cap.

A scientist, entrepreneur and inventor, Corren's the hyperintellectual to Scott's common-man persona, and he faces an uphill battle, despite qualifying for $200,000 in public financing for his campaign. Earlier this month, the Castleton Polling Institute showed Corren trailing Scott 24 to 58 percent.

This particular race may be more about personalities than politics. Even the staunchest Progressives and Democrats are hesitant to speak critically of Scott, whose political stances tend to be moderate and quietly conveyed. "Chances are, if people know him, they like him," said Rich Clark, the director of the polling institute.

Meanwhile, Corren has to live down a hard-charging reputation — when he was one of three Progs in the legislature — for pushing an agenda that was decades ahead of its time. His challenge: to chip away at Scott's uncontroversial image without reinforcing the impression held by some political insiders that he is a self-righteous crusader.

To that end, Corren has sought to inspire Vermont voters with a vision for the lieutenant governorship that's as much about crafting policy as it is about corralling the Senate.

"We've been ... taught not to expect much," said Corren of the office. He criticizes Scott for not taking strong positions or getting his hands dirty in the work of policy making. "I just don't understand wanting to get less work out of somebody rather than more ... I think more is more."

Mr. Nice Guy

Scott, 56, grew up in Barre, racing snowmobiles, hunting and eyeing late-model racecars he couldn't afford until he reached his thirties. He attended the University of Vermont and later started a motorcycle business that got derailed when he discovered it needed an Act 250 permit. A father of two grown daughters, Scott lives in Berlin with his third wife, a nurse.

"I don't have a political bone in my body," Scott often says, styling himself as a man of the people. But this line — like his willingness to let others win — overlooks the political acumen and competitive drive of the state's highest-ranking Republican. "He's as political as any politician in the world," declared Bob Stannard, a recently retired lobbyist and former Democratic state rep.

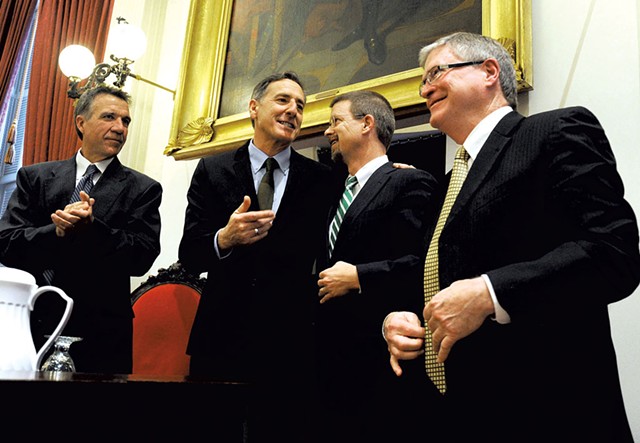

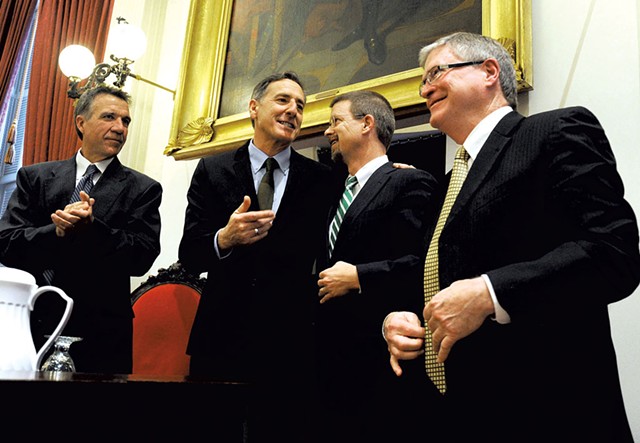

click to enlarge

- File: Jeb Wallace-brodeur

- Left to right: Lt. Gov. Phil Scott, Gov. Peter Shumlin, House Speaker Shap Smith and Senate President Pro Tem John Campbell

With Scott, the political and the personal are entwined — more so, perhaps, than with any other statehouse denizen. His blue-collar credentials are bona fide, but he also knows how to use them to his advantage. Checkered flag motifs adorn his campaign materials, and his racecar analogies remind Vermont voters of his celebrity status.

During four years as lieutenant governor and 10 as a state senator before that, Scott has developed plenty of off-the-track fans who laud his levelheaded, selfless approach to politics.

Scott Milne, the GOP candidate for governor, considers him one of the state's greatest populists.

Lobbyist Heidi Tringe described him as the ultimate retail politician.

"I wish I could clone him," said Senate Minority Leader Joe Benning (R-Caledonia).

More notably, seven of 17 Democratic state senators have crossed party lines to signal their support for Scott — including some influential ones: Dick Mazza of Colchester, Dick Sears of Bennington and President Pro Tem John Campbell of Quechee. Only five have so far endorsed Corren, but the Democrat has the support of both U.S. Senator Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.) and his junior colleague, Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.)

By his own account, Scott gets along well with Democratic Gov. Peter Shumlin, too — he described their relationship as "honest" and "trusting." The governor invites his deputy to cabinet meetings and pivotal press conferences and has done little to assist the Democratic candidates who've attempted to unseat Scott in the last two elections.

When Shumlin decided to build a house in East Montpelier, he called on his lieutenant governor to lay the foundation, build the driveway and dig the gubernatorial pond. Asked if he gave Shumlin a discount, Scott hedged. "I didn't do anything that I wouldn't do for anybody else. I didn't do it for nothing, that's for sure."

The governor isn't the only guy for whom Scott has rolled up his sleeves. Asked about his accomplishments, supporters invariably summon the memory of Scott using his DuBois Construction equipment to clean up debris from Tropical Storm Irene. Later, he raised money to remove and replace mobile homes — "without spending any taxpayer dollars," his website points out. Last weekend, for the 10th year running, he collected donated tires, which will be resold to raise cash to buy heating oil for low-income families.

Besides the Wheels for Warmth program, Scott's website calls attention to his practice of spending time in different jobs around the state. "It's not just a publicity stunt," Tringe said. "He is one of few public servants who is actually listening and observing and experiencing what Vermonters are on a daily basis."

Where Does He Stand?

Scott often invokes his experience as a small-business owner. Even when the legislature is in session, he'll show up at DuBois Construction, which he co-owns with a cousin, for a few hours in the early morning and then return for several more in the evening. "I make a point of opening the mail every day," Scott said. He also mops the floors. On a recent visit, the main warehouse was cleaner than most homes. In his office was a copy of The Vermont Way, former Republican governor Jim Douglas' memoir. Scott admitted he hasn't found the time to read it yet.

Downstairs, a dictionary-thick book lay open on a table in the conference room. Its pages were singed, and someone had attempted to reconstruct the binding using duct tape. More heavy equipment manuals — charred to various degrees — filled a nearby bookcase. In 2012, a fire destroyed DuBois Construction's office, garage and much of the heavy equipment. New manuals cost roughly $600, so Scott said he salvaged what he could.

He said the fire was one of several reasons — Scott calls them the three Ps — he hasn't run for the state's highest office. Professionally, he couldn't leave his company, because "we weren't on solid footing." Politically, "I didn't think I could win." And personally, "I wasn't ready to hang up my helmet." As in, his car-racing helmet.

Scott prides himself on being accessible — especially to those who lack political savvy. Last Wednesday, he told Vermont Public Radio's Jane Lindholm that his office has fielded as many as 2,000 calls from constituents during the last three years. Later in the interview, when a caller from Vershire asked him about a permitting problem, Scott invited him to his office. "We don't have the answers, but we can open up doors and hopefully get you in to talk about the issue."

That approach has paid off with voters. The Castleton poll showed Scott with a 59 percent approval rating among voters, 14 points higher than Shumlin's numbers.

And Scott's popularity extends into the Green Room. Even senators who've publicly said they won't vote for him — Claire Ayer (D-Addison), for example — have praised Scott's skill. The president pro tem decides which bills are brought to the Senate floor, while the lieutenant governor facilitates the debate and makes sure senators adhere to Robert's Rules, a task Scott described as part judge, part traffic cop. The lieutenant governor only votes in the event of a tie.

"Do it by the book rather than your personal agenda," is how Scott described his philosophy at the podium.

"When we get hot and heavy into confrontation, he's very good about calming the waves," Benning said, though he noted Scott has a tendency to hit the gavel too hard.

As lieutenant governor, Scott is one-third — Mazza and Campbell complete the triumvirate — of what is known as the Committee on Committees, which decides which senators sit on which policy committees and who leads them. Some senators grumble that the process is inherently opaque and politically driven. To a certain extent, it remains "an old boys' club," according to Sen. Diane Snelling (R-Chittenden).

But most concede that Scott's been reasonable there, too.

Scott's biggest vulnerability is policy. Critics say he has never really dug in. Sen. Ginny Lyons (D-Chittenden) recalled how former lieutenant governor Doug Racine would pull people into his office to hammer out ideas behind the scenes. "I personally have not seen that with Phil Scott. He's been more out doing his job thing," Lyons said.

Racine, the recently deposed secretary of human services, agreed that Scott has been "short on policy details." During his own tenure, Racine said, he convened a conference on child poverty and helped lawmakers develop the income-sensitivity portion of the property tax formula. "I think Vermonters feel very comfortable with him, but I think he could do more."

Scott's also taken flak for ducking key issues. He acknowledged that, particularly on the issue of single-payer, he's irked both Republicans and Democrats by refusing to take a clear position. He also reversed his stance on ridgeline wind turbines — in his own telling, he opposed a moratorium on them until he took bike ride near one of the developments and realized just how intrusive they were. But he insists he's just being open-minded.

"I don't know where he stands on anything," said Terry Bouricius, a longtime friend of Corren's who served alongside his fellow Prog in the Statehouse in the 1990s.

"If you don't do anything, you don't do anything wrong," said former rep and lobbyist Stannard. "Show up at the chamber of commerce and at the Boy Scouts, be happy, never commit, call it a day, and everybody loves you." Stannard said Democrats tried to recruit him to run against Scott in 2012. He declined, but that didn't stop him from devising a hypothetical campaign slogan: "Phil Scott is a nice guy, but he drives around in circles. I'm going in a straight line."

Smarty Pants

Nobody complains about not knowing where Corren stands. He is, at his core, an issues guy. If Scott is the campaign's "nice guy," Corren — by most tellings — is the "smart guy," a wonk's wonk eager to sink his teeth into policy. His platform centers on support for single-payer health care, job creation in the context of the creative economy, and a committed response to climate change.

While Scott dons a racing suit, Corren is more at ease in a business suit. During the campaign, he has hoofed it around the state talking to small businesses — a whiskey company in Shoreham, a high-tech sound company in Burlington, a bowtie manufacturer in Middlebury. At that stop, he dug into his coat pocket and somewhat bashfully showed off the homemade bowties he crafted, as a hobby, a few decades ago. "I couldn't resist," Corren said, showing good humor when one of the seamstresses grimaced at his handiwork.

He's hoping to tap into the kind of "can-do attitude" he senses among Vermonters — symbolized, in part, by last year's successful drive for legislation to label genetically engineered foods.

"You have Republicans trashing Vermont as a way to try to get elected or reelected," said Corren. "It's so counterproductive. Throw out ideas. Ask questions. Don't just trash Vermont and say, 'Everything is wrong. We're on the wrong track.'"

He said Scott and Milne have advocated for "slowing down."

"I don't think Vermonters want to go backwards," Corren said during an interview in the quiet home office from which he telecommutes to his New York City renewable energy business.

"I think we need statewide officials who are going to aspire to Vermont's best, and not play on its fears," he said.

Corren's campaign is marked by this kind of optimism. He's unwavering in his support of single-payer health care (though he acknowledges the rollout of the state's interim health program — Vermont Health Connect — has been a "disaster").

"As much as we know that the sun is going to rise tomorrow, we know that single-payer is the way to go," he said.

He's dismissive of what he calls the "old shibboleths" of fewer taxes and less regulation when it comes to economic development. He advocates for income-based property tax payments. And on the issue of climate change, he's trying to talk up the bright side: Adapting to a changing planet could mean green jobs for Vermonters.

He's also trying to appeal to the Democratic majority in Vermont. In the last weeks of the campaign, Corren's camp has turned up the heat. Last week, the campaign launched a new ad in which women — including former governor Madeleine Kunin — say that "women's rights are under attack" in the United States and mention Planned Parenthood's endorsement of Corren. The ad also claimed that Scott had been endorsed by Vermont Right to Life, which is not true. The group's political action committee simply recommended Scott as the "preferable" candidate of the two. Scott supports access to abortion but also favors parental notification.

Corren's unwavering positions delight progressive supporters — but also fuel the reputation that still lingers from his days as a state representative in the 1990s, when he and Bouricius earned the moniker "the Self-Righteous Brothers" from Vermont Times political columnist Peter Freyne.

"Politics is the art of making deals, but for these guys, deals are out of the question because they're convinced they've got it right to start with," Freyne wrote in 1994.

"[Corren and Bouricius] were really disliked for their superior ways, for their behavior and the way in which they thought they were smarter than other people and the way they derided the system ... which is born of compromise," recalled veteran Montpelier lobbyist Kevin Ellis. "They were loath to play the game."

Bouricius takes issue with Freyne's characterization, and noted that the columnist gave everyone "slightly pejorative nicknames." The idea that Corren wasn't willing to cross party lines or compromise just wasn't true, Bouricius said.

"I did not have the people skills, personality or inclination to chat up people and make friends quickly," said Bouricius, who was more interested, by his own telling, in "radical politics." Corren, on the other hand, "made fast friends very quickly across the political spectrum," said Bouricius. "He was a more natural people-person. Not to say that he is not a policy wonk as well — because he certainly is."

Corren's aptitude for policy comes up frequently in speaking with those who know him well — when words like "absolutely brilliant" and "probably a genius IQ" get bandied around. Ask his supporters about the charge that Corren can be arrogant, and they'll say he's intelligent.

"I respect and enjoy being around people who are smart," said Vermont State Auditor Doug Hoffer, who, like Corren, is running as both a Democratic and Progressive. "I don't view him as arrogant. He's self-confident, and that's fine. What's the problem with that?"

Ahead of His Time

Corren's background speaks to those smarts. He grew up in New York, and came to Vermont in the 1970s to attend Middlebury College. After graduating with a degree in philosophy in 1977, he returned to New York and completed a master's degree in energy science at New York University. His thesis proposed a plan to combat what was then commonly called "the greenhouse effect" — that is, the buildup of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and what we today simply call climate change.

It was an exciting time for energy research. After landing a job as a research scientist, Corren patented a new technology designed to harvest the energy of river and tidal currents — like a wind turbine under water. When research funding dried up, Corren reluctantly shelved the idea. In 1988, he moved to Burlington and got involved with local Progressive politics. He landed a seat on the Burlington Electric Commission, on which he served until 1994; he oversaw a $1.3 million investment in energy conservation, and negotiated Burlington's phase-out of power purchases from the Vermont Yankee nuclear power plant.

Corren made his first run — unsuccessfully — for the House in 1990. Two years later, he ran again and won — and went on to serve eight years in the House.

"It took a lot of chutzpah for him to run and get elected in those days," said Sen. Anthony Pollina (D/P-Washington). One of just three Progressives in the House, Corren was "such a minority," Pollina said, that he had to work harder to make his voice heard.

When Corren spoke up in those years, it was often on big prescient issues. According to Bouricius, Corren was the first — in the country — to introduce a motion on same-sex marriage on the floor of a state legislature. He sponsored the first legislation in Vermont calling for a single-payer health care system. He worked for six years to get a hearing on physician-assisted suicide.

"A lot of the issues that Dean was advocating for at the time, which gave people the impression that he was this adamant, hard-core Progressive unwilling to compromise, are now issues that are broadly accepted by Vermonters," said Pollina. Corren may have softened in recent years, Pollina said, but he's not the only one who has changed. Vermont has, too.

Corren's proud to have been among the first wave of legislators to push those issues. But what he's proudest of during his time as a lawmaker is a far less sexy issue: preventing the deregulation of the power industry in Vermont, a move he estimates saved Vermonters hundreds of millions of dollars.

On the topic of dollars: Corren and Bouricius came under fire in the mid-1990s for state mileage and lodging reimbursements. As Freyne reported in 1994, Corren routinely collected a $50 per diem intended for lawmakers who lived too far away from Montpelier to make the daily commute — despite the fact that he rarely stayed at his Montpelier crash pad. It wasn't illegal, but some lawmakers called it a scam.

Ultimately, the same reason Corren invoked to justify those reimbursements — the relatively low wages paid to part-time lawmakers — became the reason he did not run for a fifth term.

Corren left the Statehouse in 2000 — a move he said "broke my heart." In the years since, that neglected 1980s patent has found new life. His current employer, New York-based Verdant Power, approached Corren about reviving his long-stalled research. The company received the first-ever license from the U.S. Federal Energy Regulatory Commission for a tidal energy project. Today, the first pilot turbines are churning away beneath the surface of New York's East River.

Tweeting His Message

Corren has "mellowed with age, and with experience" since his first stint in the legislature, Pollina said.

"The question is, has he mellowed to an extent where people like him and want to vote for him?" asked Ellis. "Because there's a heck of a lot of Democrats who remember Dean Corren as being pretty righteous, pretty pure about his views and very critical of the political system in Vermont and the way business was done."

So Corren is trying to shake the image — mostly, by doing what he criticizes Vermont Republicans for failing to do: asking questions and listening.

A world away from Thunder Road, in the hip downtown Burlington coffee shop Maglianero Café, Corren and some of his campaign staffers fired up a very different kind of campaign event: a "tweet-up."

Tweet-ups are typically a chance for Twitter users to meet in person, putting a face to an online persona. In the Corren campaign's case, it was more like a digital town hall — a chance for Corren to ask questions, push his platform, and, in theory, interact with voters.

Corren, campaign manager Meg Brook and Rep. Chris Pearson (P-Burlington) huddled in front of their laptops around a small, round table. Campaign intern Emily Krasnow and Progressive Party chair Martha Abbott fiddled with their cellphones. Pearson was the tech expert of the group. Corren peered through glasses perched at the end of his nose, composing his Tweets not on Twitter but in a Microsoft Word document; he shot the tweets one by one over to Pearson, who pushed them out online.

"Every tweet-up needs some stickers," Pearson said, pasting a red Corren campaign sticker over his breast pocket.

Soon Corren hit his stride, pecking away at his laptop keyboard earnestly. "Ooh, 139!" he said, delightedly, after tallying the number of characters in one particular message. (Twitter limits messages to 140.) "Boom."

The group was quick to rib one another and laugh at their tech savvy (or lack thereof). "You can't do your two spaces after your period," Pearson chided Corren at one point. Before long, Corren was declaring the event "more fun than I expected."

Admittedly, most of the participation came from the Corren campaign itself, with staffers Brook and Dave Sterrett chiming in. A recent college grad asking questions about Corren's plans to engage young people who want to stay and work in Vermont turned out to be a campaign intern based in Middlebury.

"It's only Twitter, so I can say anything, right?" Corren quipped at one point.

In the end, though, he stayed on message: talking up the need for better health care for Vermonters, an aggressive, proactive response to climate change and the importance of the creative economy. "We must make #VT the best place on earth," he tweeted.

Role Play

To do that, Corren insists that he will take the lieutenant governor's job seriously, devoting roughly 35 hours a week to the position. He'd keep his day job, and said his employer is flexible and supportive. "I like to work," said Corren.

The job pays roughly $62,000, plus benefits.

But is any lieutenant governor, no matter how hardworking, really in the position to do that much? It depends on the person, according to former office-holders and Montpelier insiders. The minimum job duties aren't especially taxing: "They break a tie, and they have coffee," said Stannard.

When he held the position, Racine aspired to more. "I felt that as the No. 2 elected office in the state, I had a responsibility to be active in the setting of policy, and that's where I think Dean Corren has it right. Phil Scott tends to not insert himself in policy debates."

And what Scott supporters have pointed to as one of his strengths — presiding over the Senate — Corren's backers dismiss as a small part of the job. Parliamentary procedure is "child's play" for Corren, said Bouricius. Running the Senate isn't "rocket science," said Pollina, particularly with the amount of support provided by Senate staff.

"Phil does a good job of running the Senate," said Pollina, "but I don't see any reason why Dean Corren wouldn't."

Benning sees plenty of reason. "If [Corren] steps out of the role of being a moderator to advance his causes, I suspect it's going to cause him a lot of grief, because the Senate is populated with some of the strongest 30 egos the state has to offer."

Corralling those egos has been Scott's strong suit. Being nice has its value in the unabashedly clubby Senate, according to left-leaning lobbyist Ellis. "Politics is about relationships, and when you're a nice guy, that matters." He described lieutenant governors as "brokers of meetings and lubrication for conversations, running the Senate and bringing people together around thorny issues."

And then there's the issue of party affiliation. Hoffer dismissed the common refrain that the job is a ceremonial one. He pointed out that it wasn't long ago that a lieutenant governor — Howard Dean — stepped into the governor's shoes following Dick Snelling's death in 1991.

"Why would we want a Republican to be next in line for the governor's job?" asked Hoffer.

Corren isn't fazed by the disappointing numbers out of Castleton, which showed him trailing Scott by more than 30 points; the poll was taken before he started advertising on television.

Given that, pollster Clark said there's some "room for movement" in the race, pointing to the 14 percent of undecided voters. Still, Clark said, "I've got to think the incumbent is pretty happy with where he is."

Few sparks have flown during debates between Scott, Corren and the Liberty Union candidate Marina Brown. During a Burlington Free Press-hosted one, Scott surprised people by suggesting the state set up an independent board — à la Green Mountain Care Board — to regulate school spending. Corren later disparaged the proposal, telling VTDigger's Laura Krantz that it amounted to a "total state takeover" of school spending.

When it comes to campaign spending, public financing will only go so far. Vermont's campaign-finance law allows candidates to qualify by gathering a large number of small contributions from voters in lieu of money from corporations or PACs. After he scored that funding, Corren was forbidden from raising any more money. Scott has already raked in more than $250,000, exceeding Corren's war chest.

Corren optimists point out that Scott's last challenger — Cassandra Gekas — made a good showing two years ago, garnering 40 percent of the vote to Scott's 57 percent despite entering the race late, raising very little money and lacking much statewide name recognition. Gekas, however, made her bid in a year when Barack Obama was running for president, and Democrats turned out in large numbers to vote for him.

At Thunder Road earlier this month, both Corren and Scott lined up for a tradition in Vermont politics: the annual cow chip toss. After the friendly competition, Corren strode off and Scott returned to the racetrack — where, a few minutes later, another driver knocked him out of the race.

Knocking Scott out of the lieutenant governor's office appears to be a tougher challenge.

The original print version of this article was headlined "Oil & Water"

Related Stories

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

Tags: Politics, Election, Phil Scott, Dean Corren, progressive, democrat, republican, lieutenant governor

About The Authors

Kathryn Flagg

Bio:

Kathryn Flagg was a Seven Days staff writer from 2012 through 2015. She completed a fellowship in environmental journalism at Middlebury College, and her work has also appeared in the Addison County Independent, Wyoming Public Radio and Orion Magazine.

Kathryn Flagg was a Seven Days staff writer from 2012 through 2015. She completed a fellowship in environmental journalism at Middlebury College, and her work has also appeared in the Addison County Independent, Wyoming Public Radio and Orion Magazine.

Speaking of...

-

Property Tax Relief Bill Sparks Partisan Feud

Apr 18, 2024 -

Zoie Saunders, Gov. Scott’s Pick for Education Secretary, Faces Questions About Her Qualifications

Apr 10, 2024 -

Dick Mazza Steps Down From Vermont Senate

Apr 8, 2024 -

Gov. Scott Vetoes Flavored Tobacco Ban

Apr 3, 2024 -

Vermont Senate Advances Bill to Make Big Oil Pay for Climate Crisis

Apr 2, 2024 - More »

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.

- 1. A Former MMA Fighter Runs a Wildlife Rehabilitation Center in Cabot News

- 2. Scott Official Pushes Back on Former State Board of Ed Chair's Testimony Education

- 3. Home Is Where the Target Is: Suburban SoBu Builds a Downtown Neighborhood Real Estate

- 4. Burlington Budget Deficit Balloons to $13.1 Million News

- 5. Vermont Rep. Emilie Kornheiser Sees Raising Revenue as Part of Her Mission Politics

- 6. Legislature Advances Measures to Improve Vermont’s Response to Animal Cruelty Politics

- 7. Dog Hiking Challenge Pushes Humans to Explore Vermont With Their Pups True 802

- 1. Totally Transfixed: A Rare Eclipse on a Bluebird Day Dazzled Crowds in Northern Vermont 2024 Solar Eclipse

- 2. Zoie Saunders, Gov. Scott’s Pick for Education Secretary, Faces Questions About Her Qualifications Education

- 3. Don't Trash Those Solar Eclipse Glasses! Groups Collect Them to Be Reused 2024 Solar Eclipse

- 4. State Will Build Secure Juvenile Treatment Center in Vergennes News

- 5. Vermont Awarded $62 Million in Federal Solar Incentives News

- 6. Queen of the City: Mulvaney-Stanak Sworn In as Burlington Mayor News

- 7. New Jersey Earthquake Is Felt in Vermont News