Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

-

Education

Education Bill Would Speed up Secretary Search…

-

News

Middlebury College President Patton to Step Down…

-

News

Overdose-Prevention Site Bill Advances in the Vermont…

- 'We're Leaving': Winooski's Bargain Real Estate Attracted a Diverse Group of Residents for Years. Now They're Being Squeezed Out. Housing Crisis 0

- Aggressive Behavior, Increased Drug Use at Burlington's Downtown Library Prompt Calls for Help City 0

- An Act 250 Bill Would Fast-Track Approval of Downtown Housing While Protecting Natural Areas Environment 0

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

Published July 1, 2015 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated July 7, 2015 at 10:02 a.m.

click to enlarge

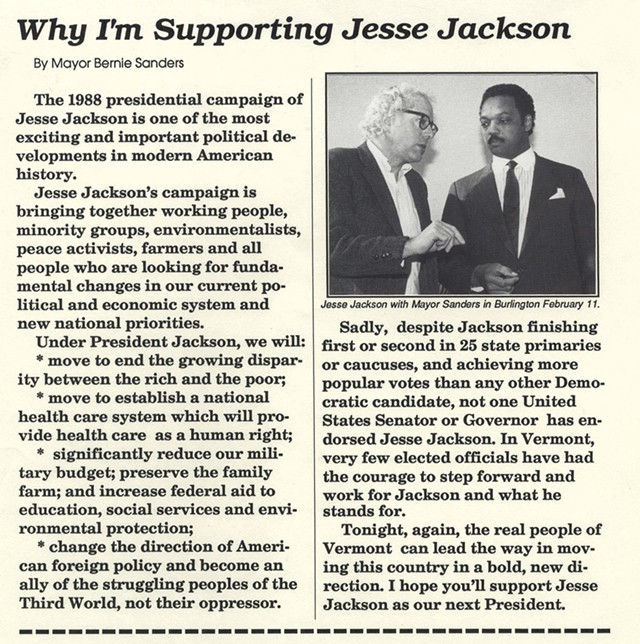

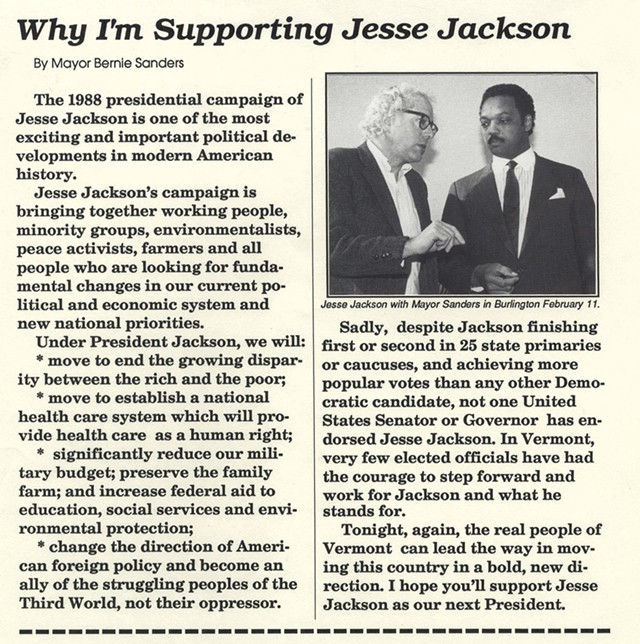

- Bernard Sanders Papers, Special Collections, University Of Vermont Library

- Material from Sanders' congressional campaign

Wanda Hines wasn't in the crowd at Sen. Bernie Sanders' (D-Vt.) official campaign kickoff, during which a series of local celebs — all white — talked up the former Burlington mayor turned presidential candidate. The African American activist skipped the festive event on the waterfront. There was no sign of Saint Michael's College prof Traci Griffith, Curtiss Reed of Vermont Partnership for Fairness and Diversity, and several other Vermont black or Latino leaders.

click to enlarge

- A young Bernie Sandersattends a meeting withcivil rights activists fromthe University of Chicago.

The absence of such figures reflects one of Sanders' greatest challenges in the race for the Democratic nomination. His growing momentum won't be sustained, many black and Latino Vermonters warn, unless he begins explicitly addressing issues centered on race.

The strong support Sanders is generating in the mostly white states of Iowa and New Hampshire, the first to respectively caucus and vote in 2016, stands in contrast to his dismal nationwide polling among nonwhites.

Just 3 percent of blacks, Latinos and Asian Americans polled recently by the Wall Street Journal and NBC News said they favored Sanders. More than 90 percent of the same group supported Hillary Clinton's candidacy.

Former governor Howard Dean, Sanders' predecessor as a presidential candidate from overwhelmingly white Vermont, got only 5 percent of the vote in the 2004 primary in South Carolina, where blacks accounted for about a quarter of the Democratic electorate. Dean received 18 percent in Iowa and 26 percent in New Hampshire.

Clinton herself was undone in the 2008 presidential campaign by Barack Obama's unshakable grip on the black vote.

Sanders' tiny degree of support in minority communities reflects his scant name recognition there in contrast with Clinton's. But it also stems from Sanders' general silence on race issues during his eight years as Burlington mayor, 16 years as a U.S. House member and nine years in the U.S. Senate.

The 73-year-old socialist has focused on class inequities throughout his career, and that emphasis encompasses many of the fundamental concerns of African Americans and Latinos. But Vermont's 95 percent white makeup means "he hasn't been forced to look at these issues through the lens of color," says Hal Colston, the African American director of Partnership for Change, a Burlington-area group advocating greater inclusiveness in public education.

Amé Lambert, a Nigeria national who works as chief diversity officer at Champlain College, points out that Sanders is "like all politicians in that he speaks to his audience." And in the second-whitest state in the nation, after Maine, "race is an especially tough thing for a politician to take on," Lambert observes.

Sanders isn't an innocent victim of his state's demographics, suggests Brattleboro-based Reed. "He's from Brooklyn and grew up with black and brown folks," he notes. Sanders' record of largely avoiding the topic of race "is simply a choice on his part that invalidates the presence of black and brown people," contends the African American activist. "Sen. Sanders suffers from a disease called color blindness."

Colston adds, "If his career had emanated from Brooklyn, he'd have a completely different perspective" on race.

Clarence Davis, a black Shelburne resident* who worked for Sanders in the House, adds that he would like to see "more discussion of race" in which his former boss would participate. It's wrong to regard the country as having achieved a post-racial consciousness, Davis suggests. "We don't live in a color-blind society and never have," he says.

The national campaign will likely push Sanders to be more forthcoming on race. Up until now, however, it has been "as if he's running again for office in Vermont rather than for national office," says Rafael Rodriguez, a Puerto Rican from the Bronx who works as a student services administrator at the University of Vermont. "He's not explicit about racism."

Sanders had a poor record as mayor in appointing minority-group members — as well as women — to high-level positions, says Hines, who has lived in Burlington since 1963. The core of his progressive entourage has been entirely white and almost exclusively male, Hines adds.

"I have a great amount of respect for Bernie," she says, "except I wouldn't vote for him." Hines is supporting Clinton, whom she regards as preferable on issues of concern to women and African Americans.

Reed offers a similar perspective, saying, "Hillary Clinton makes an effort to engage people of color wherever she is."

Sanders, by contrast, failed to consult black and brown Vermonters as he planned his presidential bid, Reed says. "Many of us have one foot in Vermont and one foot in places like D.C., New York and Philadelphia," he says. "We'd have something to offer in terms of connecting him to urban African Americans."

Reed's Vermont Partnership for Fairness and Diversity is seeking to make the state "the epicenter of inclusive thought and practice in the United States," he adds. "Bernie does not reflect that at all. He just doesn't come across as antiracist."

Sanders' call for removing the Confederate flag from the grounds of the South Carolina capitol was welcome, if belated, Reed continues: "It would be really good for Bernie to tell Vermonters to get rid of that flag. You see it all the time in southern Vermont."

Rachel Siegel, director of the Burlington-based Peace & Justice Center, says Sanders' preoccupation with class inequities makes him one of the most consistently progressive figures in U.S. electoral politics. "One of the great things about Bernie's campaign is that he stays on message," Siegel comments. "And one of the biggest drawbacks is that he stays on message."

Speaking on behalf of her organization, which includes a program devoted to race-related issues, Siegel, who is white, says, "Economic justice and racial justice are so entwined you really can't talk about one without talking about the other." But Sanders hasn't had much to say about specifically racial concerns, Siegel finds.

Sanders' reluctance to acknowledge the color line may not be solely a product of myopia or electoral exigencies. It could reflect his socialist ideology.

As a teenager, Sanders was exposed to Marxist analysis via his older brother, Larry, then a student at Brooklyn College. At the University of Chicago, where he majored in political science, Bernie Sanders joined the Young People's Socialist League, a Marxism-influenced group that was explicitly anticommunist. Although he has never been a dogmatist or an ideologue, it's clear that Sanders' thinking reflects the socialist tradition of putting primacy on issues of economic class.

Many socialists see "identity politics" — which give precedence to skin color, gender and sexual orientation — as a potentially divisive element within the ranks of the working class. From this perspective, placing primary emphasis on race hinders progress toward the fundamental socialist goal of "uniting all who can be united" in opposition to the ruling class.

Sanders came close to staking out that position in an interview on National Public Radio in 2014. "You should not be basing your politics based on your color," he said then. "What you should be basing your politics on is, how is your family doing?"

In the same interview, conducted shortly after the Republican triumph in midterm congressional elections, Sanders suggested that the white flight from the Democratic Party resulted from its failure to confront "big-money interests." The socialist senator had nothing to say about the role racism plays in white voters' majority support for Republican candidates.

While acknowledging that Sanders "does approach things from a class background," campaign manager Jeff Weaver points out: "Bernie's origins in politics are in the civil rights movement." Sanders signed up at the University of Chicago with the Congress of Racial Equality. He was arrested while a student at a sit-in against housing segregation in Chicago. Sanders also took part in the 1963 March on Washington that culminated in Martin Luther King Jr.'s "I Have a Dream" speech.

As mayor of Burlington 25 years later, Sanders endorsed Jesse Jackson's candidacy for the Democratic presidential nomination. The mayor also took part in the Vermont Democratic caucus that year that gave the African American candidate a nationally headlined victory.

Sanders got slapped in the face for his efforts. Helen Malloy, a Democratic stalwart, was enraged that a vehement critic of the party's record participated in its caucus.

No one suggests that Sanders has taken stands in opposition to blacks' and Latinos' views during his decades in Congress. Weaver notes that his boss "works closely with the Congressional Black Caucus," and most of the sources of color interviewed for this story say they appreciate Sanders' consistent and outspoken advocacy of social and economic equity.

Abel Luna, an organizer for the Burlington-based Migrant Justice organization, says Sanders has been "very supportive of immigration reform." The senator has responded commendably to many of the concerns of the state's 1,600 immigrant farmworkers, "but he could be doing more," Luna comments, adding, "He often speaks of American workers in ways that don't recognize the situation of undocumented workers."

Sanders does have at least one unequivocal fan among African Americans who have known him well. Dolores Sandoval, a Democrat who lost to Sanders in the race for the U.S. House in 1990, says, "It's always been my impression that he's been good on racial issues." She singles out his 2002 House vote opposing the U.S. invasion of Iraq, which Sandoval describes as "a racist endeavor."

Sandoval predicts that Sanders "is going to get support in the black, Latino and other minority communities because he's talking about jobs."

Cornel West, a leading public intellectual and African American activist, also confesses to a bromance with the grumpy Vermonter. "I love brother Bernie," West gushed in a recent interview with Laura Flanders of GRITtv. "He tells the truth about Wall Street. He really does."

But the political relationship may not be consummated. West cautioned that he's not ready to endorse Sanders out of fear his bro could wind up throwing his support to Clinton. He has no love for the former secretary of state. Nor is West pleased that Sanders hasn't forcefully condemned Israel's occupation of the West Bank. "I don't hear my dear brother Bernie hitting that, and I'm not gonna sell my precious Palestinian brothers and sisters down the river only because of U.S. politics," West told Flanders.

Champlain College diversity officer Lambert, who came to Vermont four and a half years ago, likewise sees reason to admire Sanders. Citing the speech he gave last January as part of Burlington's tribute to King, Lambert says, "It was clear he had familiarity with racial justice issues."

Sanders is starting to address those issues as the presidential nominating contest gains momentum. In response to an accused white supremacist's mass murder in a Charleston, S.C., black church on June 17, Sanders excoriated "the ugly stain of racism that still taints our nation."

And in a national TV interview on June 28, Sanders said his campaign centerpiece proposal for a massive federal jobs program "applies even more to the African American community and to the Hispanic community." He also pledged to "make a major outreach effort to those communities, let people know my background, let people know my record."

The outreach has begun, with Weaver telling Seven Days that the presidential campaign is hiring African American activist Marcus Ferrell as political director for the southeastern states. Sanders aides also say the candidate will speak increasingly and critically in the coming weeks about police brutality, the War on Drugs, corporate prisons and other issues that get close attention from black and Latino voters.

"The best thing he can do is to surround himself with people knowledgeable on those issues," suggests Griffith, a professor of journalism at St. Michael's College. If he takes that and other race-conscious steps, she adds, "I don't think it'll be impossible for him to make a connection with people of color."

Partnership for Change's Colston is similarly optimistic, and he did attend the campaign kickoff. "He's going to grow," he predicts. "He's already growing."

Minorities may also find it appealing that Sanders seldom seems patronizing, says Kyle Dodson, an African American member of the Burlington school board. While echoing the misgivings many blacks and Latinos express regarding Sanders' general quiescence on race, Dodson declares, "I do like the independence of his thought. He's probably the politician I trust the most."

Correction 7/7/15: An earlier version of this story stated that Clarence Davis lives in Burlington; in fact, he lives in Shelburne.

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

Tags: Politics, Senator, Bernie Sanders, immigration, race, politics, Presidential Campaign, Video, Recommended Reading

More By This Author

About The Author

Kevin J. Kelley

Bio:

Kevin J. Kelley is a contributing writer for Seven Days, Vermont Business Magazine and the daily Nation of Kenya.

Kevin J. Kelley is a contributing writer for Seven Days, Vermont Business Magazine and the daily Nation of Kenya.

Speaking of...

-

Vermont Awarded $62 Million in Federal Solar Incentives

Apr 22, 2024 -

Man Charged With Arson at Bernie Sanders' Burlington Office

Apr 7, 2024 -

Police Search for Man Who Set Fire at Sen. Bernie Sanders' Burlington Office

Apr 5, 2024 -

Bernie Sanders Sits Down With 'Seven Days' to Talk About Aging Vermont

Apr 3, 2024 -

Sociologist and Author Nikhil Goyal Talks Education, Books and Bernie

Dec 6, 2023 - More »

Comments (9)

Showing 1-9 of 9

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.

- 1. 'We're Leaving': Winooski's Bargain Real Estate Attracted a Diverse Group of Residents for Years. Now They're Being Squeezed Out. Housing Crisis

- 2. Middlebury College President Patton to Step Down in December News

- 3. Aggressive Behavior, Increased Drug Use at Burlington's Downtown Library Prompt Calls for Help City

- 4. Through Arts Such as Weaving, Older Vermonters Reflect on Their Lives and Losses This Old State

- 5. Overdose-Prevention Site Bill Advances in the Vermont Senate News

- 6. High School Snowboarder's Nonprofit Pitch Wins Her Free Tuition at UVM True 802

- 7. Help Seven Days Report on Rural Vermont 7D Promo

- 1. Totally Transfixed: A Rare Eclipse on a Bluebird Day Dazzled Crowds in Northern Vermont 2024 Solar Eclipse

- 2. Zoie Saunders, Gov. Scott’s Pick for Education Secretary, Faces Questions About Her Qualifications Education

- 3. Don't Trash Those Solar Eclipse Glasses! Groups Collect Them to Be Reused 2024 Solar Eclipse

- 4. Aggressive Behavior, Increased Drug Use at Burlington's Downtown Library Prompt Calls for Help City

- 5. State Will Build Secure Juvenile Treatment Center in Vergennes News

- 6. Vermont Awarded $62 Million in Federal Solar Incentives News

- 7. New Jersey Earthquake Is Felt in Vermont News