Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

Published July 3, 2019 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated July 5, 2019 at 11:35 a.m.

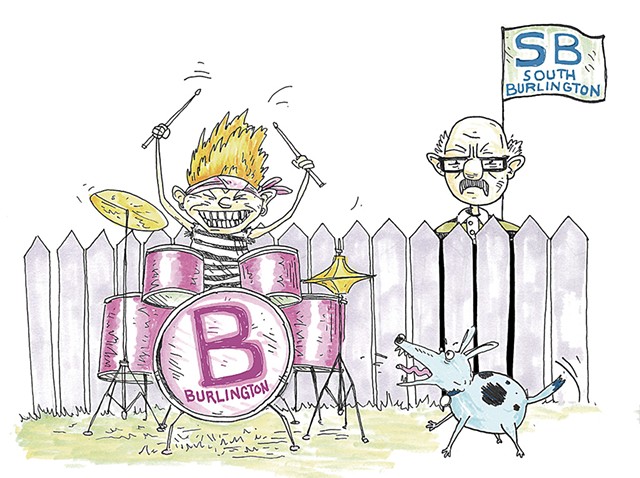

South Burlington and Burlington split from each other way back in the Civil War era. But like ex-spouses who haven't buried the hatchet, they still squabble — and sometimes have major rows.

Case in point: the recent fracas over a Burlington City Council decision that paves the way for concert venue Higher Ground to relocate to the Burton Snowboards complex in that city's South End, within spitting distance of the city line.

South Burlington Councilor Meaghan Emery roundly chastised her Burlington counterparts for the zoning change approval and decried the noise and traffic that it could mean for SoBu's Queen City Park neighborhood, a quiet enclave of homes on Shelburne Bay. Her city wasn't given enough time to weigh in, she said.

"This is going to have a major impact here," Emery said. "It is a source of frustration."

Emery is now floating an idea to restrict the popular Red Rocks Park between Burton and the Queen City Park neighborhood to South Burlington residents only. The 100-acre woodland with scenic views and cliffs that plunge into Lake Champlain draws visitors from around the region. Heavy use is damaging trails, and dog waste is such a problem that Green Up Day volunteers picked up roughly 150 pounds, Emery said.

Burlington officials point out that they sent public notice of the zoning change meetings to South Burlington's planning department, and the meetings were publicly warned — and got news coverage. "That's on them" to engage in the public process, Burlington City Council President Kurt Wright (R-Ward 4) said. He's also annoyed by Emery's proposal for Red Rocks.

"It sounds like a tit-for-tat threat response," he said. "I think that's ridiculous, totally ridiculous. Does she know who's not cleaning up after their dogs?"

"I think this project should not have been a surprise to anyone," Burlington Mayor Miro Weinberger told Seven Days. "If Councilor Emery had a concern about it and wanted us to respond to that concern, not just to grandstand, I think she should have done her outreach much sooner, and it should have been backed up by an action of her fellow board members."

Disputes such as this are hardly new. Disagreements about the Burlington International Airport — owned by Burlington but located in South Burlington — have led to friction and even litigation between the cities. And in the not-so-distant past, Burlington officials were quick to challenge the University Mall build-out in SoBu, fearing economic competition.

The cities have been at odds as far back as 1865, when they split what had been one large town. Residents in the center of Burlington, then known as a village, wanted to overhaul the village waterworks following outbreaks of typhoid fever, writer Barry Salussolia noted in a 1986 Vermont History article. Business leaders also believed they could better grow lumber and manufacturing industries with a mayor and aldermen, as opposed to the town meeting model of governing that they believed was slow and ineffective.

Not surprisingly, residents in the rural areas did not want to pay taxes for water lines that would not extend to them and fire service that wouldn't reach their farther-flung farms. So with the blessing of the Vermont legislature, residents opted to divide the town.

Today, the cities in some ways could not be more different. Burlington, with 42,239 people, has managed to turn its historic downtown into a major tourist draw with the pedestrian-only Church Street Marketplace and preserved historic buildings including city hall, decorated by marble Corinthian pilasters and a golden cupola.

It's not all grand, though. Potholes and parking are constant sources of complaint, and unpleasant aromas from the city's main sewer treatment plant sometimes distract from the stunning lake views.

SoBu still retains some rural areas but has largely evolved into a suburb of 19,000. The city takes pride in its public schools but has shown less ambition when it comes to architecture and design. Strip malls clutter its thoroughfares, and city hall could be mistaken for a dentist's office. For years, the University Mall, with its football fields of parking, was the closest South Burlington came to having a downtown.

No longer content to be faceless, South Burlington is now building its own city center, a multimillion dollar project east of Dorset Street. Burlington, meanwhile, is worriedly gazing at the "hole," an empty lot where the stalled CityPlace project's condos, offices and shops are meant to revitalize the site formerly occupied by the Burlington Town Center mall.

Competition for commerce has been a major flash point between the two cities for at least 40 years.

"There were times when we didn't feel like we had a seat at the table," former Burlington mayor Peter Clavelle recalled. "Most significantly, I'm thinking of the expansion of University Mall, which directly competed with downtown Burlington."

Burlington attempted unsuccessfully to block the steady expansion of the U-Mall in Act 250 proceedings in the mid-1980s, Clavelle recalled. The Queen City argued that the shopping center constituted commercial suburban sprawl and also insisted that South Burlington should help shoulder the need for affordable housing in the region if it were to bring in more low-paid retail workers to staff its retail stores.

That argument didn't really fly in the permitting process. But in recent years, South Burlington has added a significant number of affordable units and deserves to be recognized for that, Clavelle said.

Most memorably, the cities have feuded over the Burlington International Airport, which sprouted in a farmer's field a century ago. In 2012, South Burlington dramatically increased the airport's tax assessment. A four-year court battle ensued, and the two cities ultimately agreed to a compromise settlement in 2016 under which the property's valuation was dropped from $77 million to $52 million.

A home demolition program has created even more tension. Since the 1990s, more than 140 homes near the airport have been destroyed using Federal Aviation Administration noise mitigation funds at the direction of Burlington officials. Now F-35 jets — louder even than the F-16s they are replacing — are set to arrive this fall at the Vermont Air National Guard base at BTV. The military jets have the blessing of Mayor Weinberger, who supports the basing even in the face of opposition from both the Burlington and South Burlington city councils.

There has been a push to find common ground. Two years ago, South Burlington City Councilor Tom Chittenden led a failed effort to make the airport a regional government entity. Burlington should not have rights to control the airspace over Chittenden County just because the city bought a cornfield 100 years ago, Chittenden said.

"It's like if they were deciding how Lake Champlain was used for the entire region," Chittenden said. "The lake, as well as the airspace, is a public good."

It isn't all sparring, though, between the neighboring cities. Recently they collaborated on a regional dispatch system, for example. The two city councils have also passed resolutions to enter a contract, along with Winooski, for an electric bicycle rental and docking station program. And they've lobbied jointly for the legislature to protect and expand the tax-increment financing system that has helped both cities aid major downtown projects.

Most surprising to some: The two cities' public schools have begun to collaborate on a high school football program. A dwindling number of players at each school triggered the union.

The athletic rivalry had been ugly at times. In 2006, South Burlington student fans chanted "welfare, welfare" and "food stamps" as their Rebels took on Burlington's Seahorses in a varsity basketball game.

Nevertheless, the high schools debuted a joint varsity football team last fall. South Burlington High School has traded the Rebels moniker for the Wolves; the combined team is called the SeaWolves.

It's worked well, said head co-coach Brennan Carney, a history teacher at Burlington High School.

"They were a team," he said. "One united SeaWolves team, which was awesome to see." Some of the old rivalries dissipated, he said: "The kids were very keen on connecting. They were friends right away."

Carney was initially more worried about parents and adults in the stands, but they, too, came together, he said.

The next competitive proving ground could be the Burlington Development Review Board. That's where Burton must win approval for a proposal to redevelop its campus to include a large space for nightclub Higher Ground. Emery has vowed to contest the project.

Burton has not filed an application yet and expects design and permitting to take six to 12 months. If approved, construction and remodeling could go 18 to 24 months beyond that, according to Justin Worthley, Burton's senior vice president of global human relations.

Helen Riehle, chair of the South Burlington City Council, said communication between the two cities over the airport has improved. Now she's hoping that there can be more discussion about traffic, noise and nighttime wanderings into Red Rocks Park before the Higher Ground venue is approved. The bottom line?

"People just really want to be heard," she said.

Related Locations

-

Patrick Leahy Burlington International Airport

- 1200 Airport Dr., South Burlington Chittenden County VT 05403

- 44.46907;-73.15540

-

Be the first to review this location!

Related Stories

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

More By This Author

Speaking of...

-

Burlington Budget Deficit Balloons to $13.1 Million

Apr 25, 2024 -

The Café HOT. in Burlington Adds Late-Night Menu

Apr 23, 2024 -

Burlington Mayor Emma Mulvaney-Stanak’s First Term Starts With Major Staffing and Spending Decisions

Apr 17, 2024 -

Home Is Where the Target Is: Suburban SoBu Builds a Downtown Neighborhood

Apr 16, 2024 -

State Will Build Secure Juvenile Treatment Center in Vergennes

Apr 15, 2024 - More »

Comments (6)

Showing 1-6 of 6

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.

- 1. A Former MMA Fighter Runs a Wildlife Rehabilitation Center in Cabot News

- 2. UVM, Middlebury College Students Set Up Encampments to Protest War in Gaza News

- 3. Scott Official Pushes Back on Former State Board of Ed Chair's Testimony Education

- 4. Burlington Budget Deficit Balloons to $13.1 Million News

- 5. Home Is Where the Target Is: Suburban SoBu Builds a Downtown Neighborhood Real Estate

- 6. Dog Hiking Challenge Pushes Humans to Explore Vermont With Their Pups True 802

- 7. Senate Committee Votes 3-2 to Recommend Saunders as Education Secretary Education

- 1. Totally Transfixed: A Rare Eclipse on a Bluebird Day Dazzled Crowds in Northern Vermont 2024 Solar Eclipse

- 2. Zoie Saunders, Gov. Scott’s Pick for Education Secretary, Faces Questions About Her Qualifications Education

- 3. Don't Trash Those Solar Eclipse Glasses! Groups Collect Them to Be Reused 2024 Solar Eclipse

- 4. State Will Build Secure Juvenile Treatment Center in Vergennes News

- 5. Vermont Awarded $62 Million in Federal Solar Incentives News

- 6. Queen of the City: Mulvaney-Stanak Sworn In as Burlington Mayor News

- 7. New Jersey Earthquake Is Felt in Vermont News