Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

-

Education

Scott Official Pushes Back on Former State…

-

News

Burlington Budget Deficit Balloons to $13.1 Million

-

Education

Senate Committee Votes 3-2 to Recommend Saunders…

- Court Rejects Roxbury's Request to Block School Budget Vote Education 0

- Norwich University Names New President Education 0

- Media Note: Mitch Wertlieb Named Host of 'Vermont This Week' Health Care 0

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

How Vermonters Are Coping With Being Apart In the Pandemic

Published November 25, 2020 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated December 22, 2020 at 5:12 p.m.

- Annelise Caposella

Vermonters have entered a lonely season. After a summer of cautious optimism that the state's diligent public health measures had contained the spread of COVID-19, the fall brought a depressing reality check. Over the last month, Vermont has logged 45 percent of its 3,762 total confirmed cases; the average number of new infections each week has climbed 423 percent since the beginning of November. After 99 days without a COVID-19 death, the state has recorded six within the past three weeks.

In an attempt to control the surge, Gov. Phil Scott has effectively banned all social gatherings, indoors and out, with some provisions for people who live alone or need to leave an unsafe housing situation. But for the most part, we've returned to the bleakly familiar territory of hunkering down with whomever we happened to be cohabitating when the music stopped.

"In Vermont, we had this illusion of being protected, and I think that people are shocked about what this means for them," said psychologist Cath Burns, the clinical consultant for COVID Support VT, a mental health program that launched this summer.

In a pandemic, our relationships are both lifelines and sources of risk, a contradiction too bizarre to fully assimilate. What's even harder to grasp is how these last eight months have rewired us as social animals, and whether the behaviors we deemed "normal" in the Before Times will ever seem completely normal again.

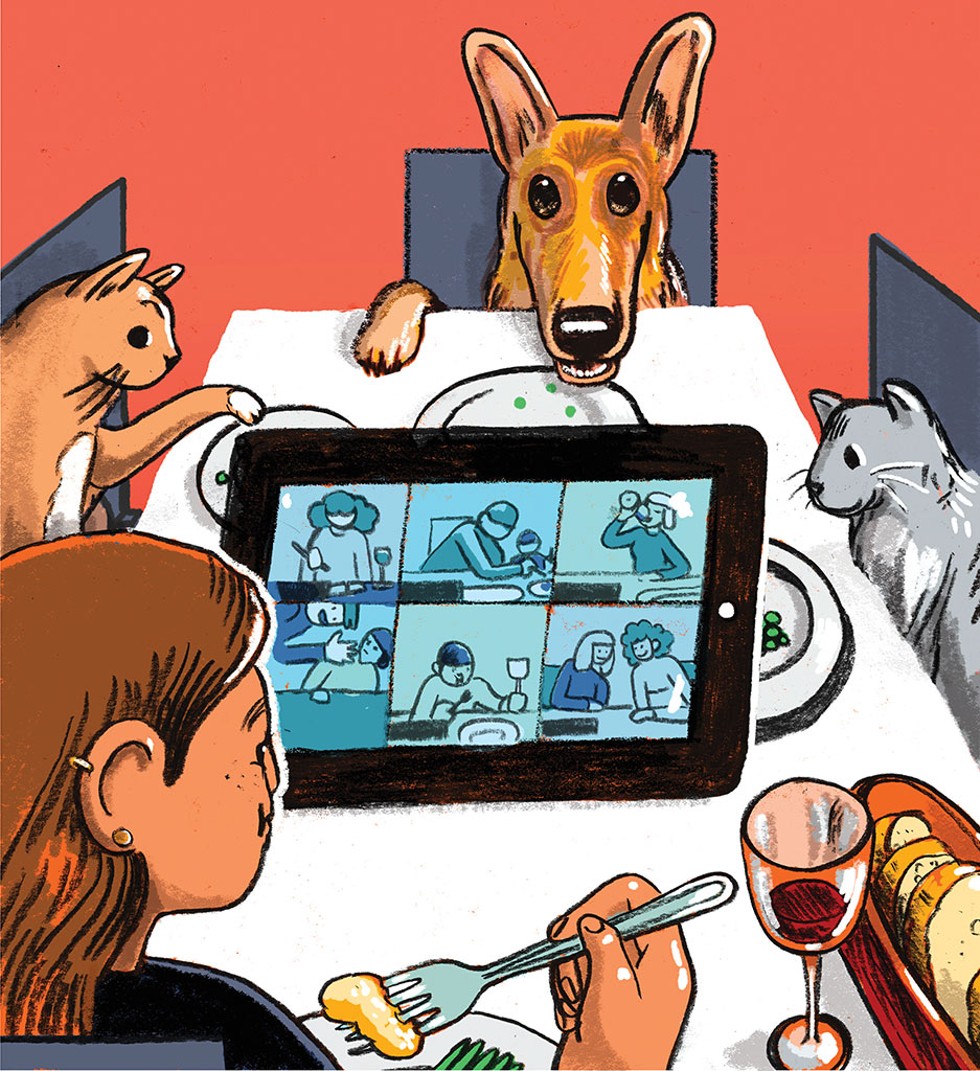

As we enter the holiday season, the loss of normalcy feels acutely painful, even if the internet is awash with chipper guides to making our virtual feasts feel less dystopian. Perhaps more usefully, in October, COVID Support VT embedded three crisis counselors in the state's 2-1-1 helpline service. In the past month and a half, Burns said, the line has been getting steadily busier; each counselor is now fielding an average of 20 calls a day.

"A lot of callers are talking about being depressed and lonely about not being able to be around their friends and family for the holidays," she said. "People are feeling incredibly isolated and far away from the people they care about."

Flawed Instincts

Our alienation from one another is both individual and systemic. Beyond the unifying calls to collective action — we're in this together! — there is no single reality of the pandemic. Those lucky enough to work remotely Zoom and bake and binge-watch Netflix, while essential workers literally cannot afford to stay home. We exist in different socioeconomic, political and informational ecosystems; we are all susceptible to COVID-19, but we are not equally vulnerable to it.

While the shrinking of personal worlds has widened the distances between people, it seems to have collapsed others — most uncomfortably, the distance between ourselves and ourselves. Erica Heilman, creator of the podcast "Rumble Strip," lives with her 17-year-old son in St. Johnsbury; lately, she's been contemplating what this intense period of hermitage means for our species.

"There's a haziness to the experience of living with myself, and myself, and myself, so much of myself. My kid goes to school twice a week, and then he's with himself and himself and himself, which is not what a 17-year-old should be doing," she said. "How much of ourselves can we manage?"

At first, those of us who were dutifully self-isolating thought in terms of distinct and separate pods: walking friends, picnic friends, car friends, indoor masked friends, indoor unmasked friends. But, as it turns out, humans are intrinsically bad at recalibrating their lives around an invisible threat. No electric buzzer lets us know that we've exhaled too hard in the wrong direction, or that the last person we hugged had been exposed to the coronavirus minutes before.

"Our mental equipment does not do a great job of thinking statistically, probabilistically," said Lee Rosen, an assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Vermont's Larner College of Medicine.

"I think the experience of being in Vermont has given people this greater sense of freedom — this idea that 'I have behaved well, and I'm pretty sure that the people I'm going to see have behaved well, so therefore I can see them," he said. "The desire to connect pulls us to not see what we don't want to see."

As Human Services Secretary Mike Smith recently put it to Seven Days: "Some Vermonters started believing in their own magic."

Since October 1, 71 percent of new COVID-19 cases in Vermont have been associated with private gatherings — backyard barbecues, dinner parties — where people likely thought of one another as safe and trustworthy. But interpersonal trust can also lead us to mistake comfort for safety; the current surge has made it devastatingly clear that we are worst at assessing risk when we're in familiar situations with people we know well.

The drive for social acceptance, Rosen explained, can be powerful enough to keep people from speaking up when they feel that their family and friends aren't exercising good judgment. The same impulse can also motivate us to conceal our own risk factors from our close contacts.

"If one of my teenagers were exposed to COVID at school, and then I became exposed, it would be deeply uncomfortable for me to inform my students, my colleagues and anybody who's been around me," Rosen admitted. "But a healthy coping strategy involves addressing those difficult feelings.

"The reward for doing the right thing doesn't lie in our own gratification," he added, "but in the feeling of protecting our community."

Caring as an act of denial — skipping a family gathering, not hugging your grandmother — feels unnatural, and yet a public health crisis demands that we override our flawed instincts.

"I think it's still hard, but I think the incentive is probably more natural now, because people literally see the rising numbers," said Vermont Deputy Health Commissioner Tracy Dolan. "They're more likely to know people who are either a contact or a case."

Dolan, who has done HIV prevention work in Canada and sub-Saharan Africa, sees similarities between the cyclical resurgence of HIV within a community and the trajectory of coronavirus infection rates.

"In HIV prevention, we normalize new, safer behaviors, but over years, as people stop seeing it within their communities, they start to relax, and that leads to new outbreaks," she explained. "We're seeing that with COVID, where people were very concerned in March and April and doing a really great job. Then, when the numbers didn't go up over the summer and even into the early fall, they started relaxing a bit."

Dolan's biggest fear right now is what will happen during the first week of December, post-Thanksgiving. "We are so worried that we're going to see a surge," she said. "These measures might feel extreme right now, but we need to go this far. We desperately need to stop this in its tracks."

Untouchable

The moratorium on multi-household socializing somehow feels worse now than it did in March, perhaps because Vermonters had a summer of slight respite. We made very good use of camp chairs; we entertained various schemes to stay warm while hanging out outside.

Some people, like Lauren MacKillop, the coordinator of UVM's Early Childhood PreK-3 and Early Childhood Special Education programs, had high hopes for their backyard fire pits. At the beginning of November, MacKillop, who lives in Shelburne, was thinking of acquiring some extra sleeping bags. "I thought that we can suit up like California raisins around the fire," she said.

She and her friends had been discussing possibilities for hot cocktails — "steeping lots of different herbs, getting super witchy about it."

Last month her 29-year-old stepdaughter, Amara MacKillop, who works at a nonprofit community health center in Burlington, went so far as to give a PowerPoint presentation over Zoom to everyone in her family pod, outlining the expectations for getting together safely. Now, there will be no getting together at all. To stay sane in the meantime, Lauren MacKillop plans to gather with her friends on Zoom for something called "stitch and bitch," or bemoaning the state of the world while making samplers that say things like "Don't worry, dishes, no one is doing me either."

Kae Burdo, a 31-year-old writer and activist who works in digital marketing, said that being in polyamorous relationships has provided good practice for negotiating COVID-19 boundaries. "I definitely entered this situation with the emotional resiliency to hear answers I didn't like," said Burdo, who uses they/them pronouns.

Burdo and their wife choose to live separately in Burlington. Since the pandemic began, the two have seen each other just three times — Burdo's mother-in-law is in a vulnerable age category, and for a time, Burdo was living with another partner who worked a high-risk job. But that relationship recently ended; now, Burdo is not particularly stoked about living alone.

"I would say, in general, that cohabitation isn't really my thing, and I'm not a hypersexual person," said Burdo. "But in a situation like this, you're not having physical contact with anybody, because you're not able to see anybody. I think the hardest part about all of this is that there's no such thing as casual touch anymore."

Heilman said she can count on one hand the number of people she's touched within the last nine months. "I dream about touching people," she said.

Jim Duval, a tattoo artist in Essex Junction, hears about this all the time from his clients. "I work through people's stuff while I'm hurting them all day, and I can't tell you how many of them say they miss being touched," he said. (Tattooing, arguably an extreme form of touch, has been in high demand lately; since Duval reopened his studio in May, he's been booked out months in advance.)

For the elderly who live alone, the pandemic has been especially difficult. "Loneliness was a public health crisis for seniors even before COVID hit," said Molly Dugan, director of Support and Services at Home, which assists the elderly and adults with special needs who live independently. "What they're experiencing now is dehumanizing."

Dugan's mother-in-law, 82-year-old Dee Howe, lives by herself in an apartment at Kelley's Field, a senior housing facility in Hinesburg. For Thanksgiving, Dugan and her family had planned to invite Howe to their home in Richmond, as is the family's annual tradition. But when the governor announced recently that he wasn't planning on being with his mother for the holiday, Dugan and her husband realized that having Howe over was a bad idea.

Dugan's husband broke the news to Howe in person, standing outside and six feet away from her. "She cried a little," Dugan said. "But she understood that it was the right thing to do."

Instead, Dugan and her college-age daughters will bring Howe a to-go container of Thanksgiving dinner, then Howe will join the family feast via Zoom.

"My family takes very good care of me. I may be alone, but I'm not lonesome," Howe said. "And you know what else? I'm not bored, either. I can knit." One thing she knows she'll miss, though, is eating potato soup on Christmas Eve with Dugan and her family after the evening church service.

"Oh, that soup," she said. "I just love that soup."

Tight Bubble

Christine White, who lives in Burlington's New North End, has watched her two children, ages 7 and 10, struggle to make sense of the new boundaries. Early in the pandemic, she and another family took their kids to an empty parking lot for a bike-riding play date, figuring that would allow for social distancing. Within 10 minutes, she said, the kids had invented a game in which they were chasing around a coin and bumping into each other constantly.

The parents immediately pulled the plug on the outing. White's daughter, age 7, started to cry, thinking she was being punished. "She kept saying, 'I didn't know we would be so close!'" White said.

White, an associate at Vermont Energy Investment Corporation, has wanted to keep the rules as consistent as possible for her kids. "I'm a scientist, and I'm definitely a rule follower," she said. But on certain occasions, she's doubted herself. One day, she was picking up her daughter at a friend's house, and her daughter asked if she could hug her friend goodbye.

"In the moment, I said yes, because I saw how happy it made her," White recalled. "But then, when we were in the car, I told her that she shouldn't do that again." Her daughter asked why she'd said yes in the first place; White did her best to explain that grown-ups don't always make perfect judgment calls.

"This whole year has kind of sucked," she said. Her in-laws live in Seattle, and they haven't seen their grandchildren in so long that they almost don't want to look at recent photos of them. "It's too painful," White said. "There's this weird psychological stuff coming out right now."

Sometimes, this psychological stuff boils over into major conflict. In April, Tara, a thirtysomething Colchester woman, had a baby. (Because of her fraught situation, Tara requested anonymity.) The baby was colicky and immunocompromised, and the pediatrician advised that no one other than her parents be allowed to hold her. Tara and her husband both work in health care; since the beginning of the pandemic, she said, they've taken more stringent precautions than most people they know.

Tara's in-laws, who live in the Burlington area, were initially supportive of their decision to maintain a strict bubble. But gradually, she said, they became pushier.

"They would compare us to other parents they knew who were less restrictive about letting the grandparents interact with their kids," she said. "They kept saying, 'This isn't right, we're family — you're pushing us away.' They made us feel guilty, like we were depriving them of their grandchild."

In July, with the pediatrician's blessing, Tara and her husband told her in-laws that they could come over and hold their granddaughter, provided they completed a two-week quarantine first.

"We even went so far as to craft an email outlining our expectations, which were really pretty basic," Tara said. They asked the in-laws to refrain from seeing anyone else during their isolation period, but when her husband's brother visited from out of state, Tara's father-in-law hugged him. "He said, 'I guess that means we can't come over now,' and he was really unhappy," Tara said.

Meanwhile, Tara's mother had flown in to help her with the baby. She quarantined for a week in the basement — "We didn't hug. We didn't touch. We left her food in front of the garage door," said Tara, choking up. Only after her mother had a negative COVID-19 test was she allowed to meet her granddaughter.

According to Tara, her father-in-law took it as a personal affront that another member of the family had been granted visiting privileges. His reaction made Tara feel even worse. "It all seemed so contrived, as if our baby were a commodity," she said. "It was gross."

A blowout argument over the phone ensued between Tara and her husband's parents. There has been no reconciliation yet.

"This year has been so hard," Tara said. "To feel abandoned by the people who are supposed to be your champions is a massive, massive blow."

She looks for reassurance in the pediatrician's affirmation that these rigorous protocols are still necessary. It helps, if only briefly, to take the edge off her loneliness. "Every time I go in, I ask, 'Am I doing the right thing? Is this still the best thing?'"

Bonded in Solitude

When Gov. Scott issued his "Stay Home, Stay Safe" executive order in March, the strangeness of the situation gave people something to process together. The world felt precarious in new ways; everyone had a story about what was happening to them.

Shortly after the sweeping lockdown went into effect, Heilman started a podcast miniseries called "Our Show." She asked "Rumble Strip" listeners to send her recordings of their pandemic musings; for a month and a half, she was swamped with tape.

Then, abruptly, the audio stopped coming in. "It was like we were all podmates together, and then there was this seismic shift, and no one had anything to say anymore," she said.

Within her own friend bubble, the same thing happened. "For a while, we were watching all these movies together online and it was really fun, until abruptly, it wasn't," she said. "Suddenly, it felt empty. There was something vaguely depressing and irritating about it."

Over the summer, when she got together with her friends outdoors, Heilman noticed that her threshold for other people's company also had changed.

"I think I'm so used to doing exactly what I want, when I want to, in my own solitude, that I can't sustain a social circumstance for as long as I used to," she said. "I have been out with people I love, in their backyards around a bonfire, and stood up very prematurely and said, 'I'm leaving now.' And they say, 'That's great, because we don't have anything more to say.' There's just less to report. I have less to report."

And yet, Heilman said, there's something unexpectedly pleasant about knowing that everyone's life is, to some extent, on hold. All of us are in the slipstream, making things up as we go along, giving each other permission to be a little unhinged.

"When this is all over, I think I'll miss being able to call my friend Tobin and say, 'I am just letting you know that I'm going to take a nap. It's 11:30 a.m., and I think I might be done for the day,'" she said. "And he'll say, 'You do that. I'm going to take a nap in an hour. I'm right there with you.'"

The original print version of this article was headlined "Separation Anxiety"

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

About The Author

Chelsea Edgar

Bio:

Chelsea Edgar is a staff writer for Seven Days, and has written for BuzzFeed and Philadelphia magazine.

Chelsea Edgar is a staff writer for Seven Days, and has written for BuzzFeed and Philadelphia magazine.

More By This Author

Latest in Coronavirus

Speaking of...

-

Rep. Anne Donahue Is Determined to Find Out Where Patients of Vermont’s Old Psychiatric Hospital Are Buried

Mar 20, 2024 -

Noah's Arc: Noah Kahan Is Vermont's Biggest Cultural Export in Years. How the Hell Did That Happen?

Jan 31, 2024 -

Vermont Colleges School Students on Wellness as Mental Health Concerns Mount

Jan 17, 2024 -

At the Sheldon Museum, a New Director Aims to Connect Past, Present and Future

Nov 29, 2023 -

A Young Man's Path Through the Mental Health Care System Led to Prison — and a Fatal Encounter

Sep 6, 2023 - More »

find, follow, fan us: