Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Business

Cannabis Company Could Lose License for Using…

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

Browse Music

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

View All

Quick Links

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

Lake Memphremagog’s Natural Beauty Belies Worries About Contaminants and Fish With Tumors

Published July 28, 2021 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated November 23, 2021 at 8:50 p.m.

Rick Levey leaned over the side of a motorboat last week and dipped a long metal scoop into the marshy mouth of the Barton River where it enters Lake Memphremagog.

Over his shoulder, the hulking Coventry Landfill rose 400 feet above the water in the distance. On the unnatural angular hilltop of debris, heavy machinery was barely visible through haze that was tinged sepia by distant western wildfires.

Like an angler landing a prized catch, Levey carefully lifted his pole above the surface and poured the lake water into sample jars bound for a lab that will test them for 36 kinds of chemicals.

The water quality expert with the state Department of Environmental Conservation and a pair of colleagues were launching an extensive new water-sampling program in Memphremagog, the picturesque 31-mile-long waterway that straddles the U.S.-Canadian border. They and their Canadian counterparts hope to get to the bottom of troubling reports that toxic chemicals known to leak from landfills might be migrating from Vermont into the water supply in Québec.

Last fall, Québécois environmental officials found trace amounts of PFAS in the water supply for 175,000 Canadians. The polyfluoroalkyl chemicals are found in everything from Teflon cookware and stainproof carpets to firefighting foam. The results prompted Vermont and Québec officials to investigate the prevalence of PFAS in what many consider a pristine lake vital to the region's tourism economy.

Even as the team hunted for signs of threats to the lake's health, around them the waters teemed with life. A green heron flew over a shoreline thick with cattails. A turtle poked its head above the surface near the mouth of the Black River. Anglers cast lines to pull smallmouth bass, yellow perch and lake trout from the depths.

click to enlarge

- Kevin Mccallum ©️ Seven Days

- Rick Levey and Kelsey Colbert gathering water samples in Lake Memphremagog

Levey and his team spent the day gathering samples from 11 sites around Newport, the northern Vermont city built on the southern end of this scenic waterway. It was far from the first time Vermont environmental scientists have gone hunting for PFAS. The discovery of the compounds in drinking water wells around a former North Bennington fabric factory in 2016 set off a statewide scramble to identify contaminated sites. State environmental officials quickly fingered landfills, as well as wastewater treatment plants and car washes, as potential sources.

Now the search has gone international, adding a layer of complexity to the undertaking.

Collaborating with Levey was a Québécois crew that conducted a similar round of water samples on the Canadian side of the lake. Levey hopes the project will provide facts to replace what, so far, has been largely cross-border finger-pointing over the possible sources of the chemicals.

"This is certainly a situation where having data in hand will be very beneficial," Levey said. He is skeptical that the pollution detected in Canadian waters emanates from Vermont, considering it more likely that something closer to the north end of the narrow lake is responsible.

Others aren't so sure.

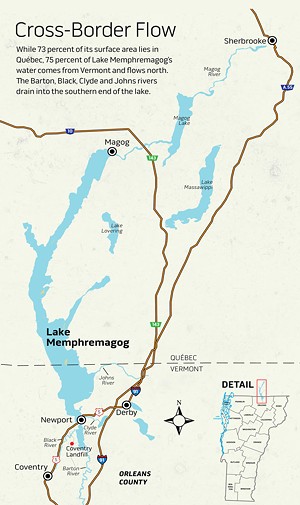

Memphremagog presents unique conservation challenges. While 73 percent of its surface area lies in Québec, 75 percent of its water flows from Vermont. That means the fate of a largely Canadian lake lies primarily in the hands of Americans.

The Barton, Black, Clyde and Johns rivers drain from the heavily forested and agricultural lands of Vermont's Northeast Kingdom into the southern end of the lake. The river water contains millions of gallons of effluent annually from four Vermont wastewater treatment plants. After entering the lake around Newport, the water slowly makes its way north for just over a year and a half, according to estimates, before flowing from the lake through the Magog River on its way to the Saint Lawrence River and, ultimately, into the Atlantic Ocean.

Concern that pollution from Vermont may migrate north and contaminate the drinking water supplies in Canada is not only based on sound science, it's common sense, said Fritz Gerhardt, a conservation scientist who has done extensive research in the watershed.

"It's easy to say it's not our problem, but we're not the ones drinking the water — the Québécois are."

Levey, however, is skeptical that the level of PFAS from Newport's plant are high enough to even be detectable — let alone a health hazard — after being diluted in trillions of gallons of lake water.

Whatever the latest round of test results show, they are unlikely to stem the rising tide of anxiety — on both sides of the border — about the health of a lake that advocates increasingly believe is in peril.

The Vermont Department of Environmental Conservation lists the lake as impaired, meaning it exceeds the levels set by regulators for certain pollutants. Following a spate of blooms of cyanobacteria, aka blue-green algae, the state in 2017 released a cleanup plan that calls for reducing the phosphorous entering the lake by 29 percent over the next 20 years, mostly by preventing runoff from agricultural lands and reducing stream bank erosion caused by more intense rainstorms.

Compounding that concern, a study in 2019 found that 30 percent of fish known as brown bullhead caught in the lake were covered with cancerous black lesions. Anglers had been reporting gross, tar-like spots on the bottom-feeding sport fish since 2012, but the joint study by the Vermont Department of Fish & Wildlife and the U.S. Geological Survey showed higher-than-expected rates and revealed that the growths were cancerous melanomas.

"It's not a small percentage. It's significant, and it indicates that something is wrong," Pete Emerson, a fisheries biologist with the Department of Fish & Wildlife, said during a public meeting on the issue last December.

Officials suggested that people not eat any bullhead with the lesions.

The cancer revelation was "mind-blowing" and a clear indicator to Peggy Stevens that, like the proverbial canary in the coal mine, the fish signal that something is clearly amiss.

"There were all these people saying, 'It's not that bad.' Well, it's bad enough that there are cancerous fish," said Stevens, a Charleston resident and a member of the anti-landfill group Don't Undermine Memphremagog's Purity, or DUMP. "You can't tell me that doesn't have something to do with the quality of the water."

Viruses, heavy metals from past industrial pollution or even the impact of ultraviolet rays on the fish in shallow bays, where most of the affected fish were discovered, could all be causes, Levey said.

Newport has been an industrial hub since the mid-1800s. It was long the home of a massive sawmill that turned timber floated down the lake from Canada into lumber shipped south by rail.

The city is still grappling with a legacy of pollution. Central Maine & Quebec Railway removed more than 10 tons of oil-contaminated soil and hazardous materials from its property on Memphremagog's South Bay in 2018. Levey said some contamination from that site could be the cause of elevated levels of metals detected in parts of the lake.

Another potential culprit, lake advocates say, is the Coventry Landfill, which has operated for decades on the southern end of the lake and remains the final destination for 80 percent of what Vermonters discard. For years, wastewater from the dump was treated at local facilities and then released into the lake.

"It's absolutely bonking mad what's going on up here," said Pam Ladds, a Newport resident and a member of DUMP.

The release of leachate has stopped, for now. But the apparent cascade of threats has some residents worried that the fate of their beloved lake, and the regional economy that depends on it, is increasingly beyond their power to protect. They fear the lake has been damaged in ways that aren't understood. State officials point to ongoing studies and planning and insist that they are keeping abreast of Memphremagog's issues.

DUMP was formed in 2018 to oppose Casella Waste Systems' proposed 51-acre expansion of the landfill, the state's last operating dump. Vermont regulators approved the growth plans in 2018 anyway, giving the landfill an additional potential 20-year lease on life — a decision that has frustrated Canadians and DUMP members.

During a recent visit to Newport's Prouty Beach, Ladds made clear her view on Vermont's lake management.

Families frolicked on the small sandy beach, and cyclists zipped past on the new bike path linking the beach to downtown and points north. Ladds pointed to erosion from the bike path construction project and trees recently removed for shoreline developments.

She said, "We're doing a piss-poor job of being stewards to this lake."

Garbage Juice

Even as advocates were still absorbing the 2019 news that high percentages of bullhead had cancer, word came last fall that trace amounts of chemicals known as PFAS had been discovered near the intake pipes for two Québec cities that get their drinking water from the lake — Magog and Sherbrooke.

Magog, a tourist-friendly city of 26,000 people, sits along the lake close to Mont-Orford National Park. Sherbrooke, the sixth-largest city in Québec and home of several universities, lies 17 miles from the lake, on the Magog River.

The levels detected — 13 parts per trillion, according to a Sherbrooke official — are below Canada's guidance of 200 parts per trillion and even Vermont's far stricter standard of 20 parts per trillion. Environmental activists and politicians in Québec nevertheless expressed alarm, some all but accusing Vermont and its lakeside landfill in Coventry of being the most likely source.

"We know there is PFAS in Québec, but we think the largest part of the problem is coming from Casella," said Robert Benoit, president of Memphremagog Conservation, the Québec-based group that advocates for lake health.

DUMP has shared that concern. The group's main victory to date has been to secure a four-year moratorium on trucking leachate, or contaminated landfill water, to Newport's wastewater treatment plant. Before then, the leachate was treated, then released, into the Clyde River just above its mouth on the lake.

Leachate is mostly rainwater that has percolated through the layers of garbage buried in the landfill, picking up all manner of toxic substances along the way. The landfill annually produces about 11 million gallons of the foul brew, sometimes referred to as "garbage juice."

The moratorium, a condition of the Act 250 permit for the expansion, prevents leachate from being treated at Newport's municipal wastewater facility until at least 2023. Casella must also explore alternative treatment options for its leachate.

Though many cheered the relief it could bring to Memphremagog, the moratorium effectively shifted the problem elsewhere — to the Lake Champlain basin. About 10 million gallons a year now go to Montpelier, where they're treated in a municipal wastewater facility and released into the Winooski River. The rest, more than 2 million gallons, goes to Plattsburgh, N.Y., which treats and discharges the water directly into the lake.

Just like Newport's, however, those municipal facilities are designed to treat sewage — not garbage juice tainted with PFAS and other contaminants, such as pharmaceuticals, that they are ill-equipped to remove. A 2018 report by the state Department of Environmental Conservation showed that the outflow from treatment plants that accept landfill leachate has significantly higher levels of PFAS.

Citing such results, Canadian officials have pressured the state not to allow leachate from the landfill to ever again be released into the Memphremagog watershed.

The state has not agreed to that condition, raising the ire of both DUMP members and their allies in Québec. Benoit, who lives on the shallow Green Bay area of the lake in Québec, said he is frustrated by the blue-green algae that sometimes chokes his shoreline, and he's worried about invasive species. But neither issue riles him as much as the idea that water from a mountain of garbage could be fouling the lake.

"We are going to fight up to the last drop of our blood not to have the leachate back in the lake," he said.

'Easy Target'

click to enlarge

- Kevin Mccallum ©️ Seven Days

- Top: Jeremy Labbe of Casella's Coventry Landfill, peering inside a new leachate holding tank. Center: The 500,000-gallon tank, which will begin filling with leachate later this year. Bottom: Two holding tanks with a combined capacity for 1 million gallons of "garbage juice"

Casella officials have not denied that the PFAS discovered at the north end of the lake could have originated from the landfill, but they have said there is no proof and point to multiple other possible sources. PFAS are now ubiquitous in the environment around the globe, so the suggestion that the landfill must be the source for the Sherbrooke samples is baseless, said Joe Fusco, a Casella spokesperson.

Stormwater from developed areas, effluent from water treatment systems in Québec and failing septic systems are all possible sources of PFAS located far closer to the north end of the lake than Coventry, he said.

"I think the landfill makes an easy target," Fusco said. "Concerns about Lake Memphremagog are valid. What's not valid is to point the finger at the Coventry landfill and say, 'This is the problem, solely.'"

The landfill dates back to the 1960s, when it was a small unlined dump and junkyard owned by Charlie Nadeau. Québec investors purchased it, then sold it to Casella in the mid-1990s.

Today the landfill accepts about 500,000 tons of waste per year. Along with the bulk of Vermont's trash, it takes sludge, construction debris and other waste from neighboring states. When all 51 acres of the expansion area are filled, the landfill will cover 126 acres.

All leachate from landfills in Vermont — even the closed ones — contains PFAS, but the levels are particularly high at Coventry. A 2019 report performed for the state by environmental consulting firm Weston & Sampson showed 3,087 parts per trillion there — 154 times higher than the 20-parts-per-trillion level allowed in Vermont drinking water. That same report, however, noted that the vast majority of the PFAS remained sequestered in the landfill.

Casella is working hard to address the problem of high PFAS levels in leachate, said Coventry landfill general manager Jeremy Labbe. One solution is structural. As part of the expansion project, the company has built a second 500,000-gallon leachate holding tank. When operational later this year, that will bring the total leachate storage capacity for the landfill to around 1 million gallons, he said. In another 20 years, the growing landfill's leachate is projected to increase to about 16 million gallons or more annually. Like all landfills, it will need to be managed for decades after that, Labbe said.

In addition, a 2019 study that Casella commissioned, by national consulting firm Brown and Caldwell, examined several alternatives to treating the leachate at municipal wastewater plants. The options range from expensive to extremely expensive.

The cheapest solution would be a mini treatment plant at the landfill using reverse osmosis and charcoal filter technology that would capture PFAS. The treated leachate would then be released into the surrounding surface water, presumably the Black River. Brown and Caldwell estimated the cost to build such a system and operate it for 20 years at $34 million to $80 million.

Another option would modernize the treatment processes at existing municipal plants, such as Newport or Montpelier, to enable those facilities to filter out PFAS. Those upgrades, plus 20-year operating costs, could run $54 million to $176 million.

The highest-cost option analyzed was one called "zero liquid discharge." This method boils the leachate down to a concentrate, not unlike making the nastiest maple syrup ever. The resulting slurry would be encased in cement — and disposed back into the landfill. The huge energy needs of such a system would ideally be met through waste heat from an existing energy plant or methane gas from the landfill. Even so, the 20-year cost estimates range from $158 million to a staggering $394 million.

Such sums would blow a hole in the bottom line even for a company as profitable as Casella, which last year had revenues of $775 million. Brothers John and Doug Casella grew their Rutland-based business from a single trash truck into a regional waste empire — a publicly traded company with 100 facilities in six states and 2,500 employees. Its stock price has soared tenfold over the last five years.

Following the bruising battle over the expansion permit, John Casella castigated landfill opponents on both sides of the border for their "scare tactics" and suggested Québec's far less stringent wastewater standards for PFAS gave Canadians little room to talk smack.

"Let's refocus our passion and resources on making sure that we have safe and environmentally sound products entering our state," Casella wrote, "and that our neighbors in Canada do their part to protect the environment."

Casella's effort to deflect criticism has been hampered of late, however, by a large leachate spill at another landfill it runs, in Bethlehem, N.H.

Approximately 154,000 gallons of the brew escaped from its holding tanks over a weekend in May following what the company has said was a pumping malfunction. State officials said the leachate escaped a retention pond and ran into a grassy area near the Ammonoosuc River. The company was already defending a federal lawsuit that the Conservation Law Foundation and the Toxics Action Center (now called Community Action Works) filed in 2018, alleging that Casella violated the Clean Water Act by allowing landfill leachate and polluted groundwater to flow from the New Hampshire dump into the river.

Last week, New Hampshire officials requested a detailed review of Casella's leachate management by August 1, after blaming the company for "failure to operate and maintain the leachate management system in a manner that controls to the greatest extent practicable spills."

City on the Lake

click to enlarge

- Bear Cieri

- Brandon Grenier (left) and Noah Crogan preparing to go bass fishing on Lake Memphremagog

People have inhabited the shores of the lake for millennia. Memphremagog was the heart of the Western Abenaki homeland; the named they bestowed on it means "big expanse of water." Like the Native people they displaced, Europeans settled on its shores, fished its depths, and plied it for transportation and trade.

Newport, whose fortunes have been tied to the lake for centuries, is now trying hard to strengthen those bonds. As the city has slowly shed its industrial past as a timber and rail hub of the Northeast Kingdom, it has sought to capitalize on its prime waterfront location to attract recreation-minded tourists. (Learn about recreational and educational cruise boat the Northern Star here.)

"Newport is like a mini Burlington, when you get right down to it," David Converse said. He's the president of the Memphremagog Watershed Association, a Newport-based group founded in 2007 to advocate for and carry out water quality projects in the basin.

Newport depends on its waterfront for its economic prosperity, Converse said. Several marinas draw boaters and anglers from Québec and beyond. Despite water quality concerns, demand for waterfront real estate is strong, said broker Tina Leblond. She just sold a 10-acre waterfront lot whose buyers plan to build a home, and she has a $2.4 million waterfront home listed in Newport.

Water quality concerns can scare off buyers, however, and Leblond thinks more needs to be done to keep the lake healthy and address the myriad threats.

"I have had people who have been interested in lakefront property on Memphremagog, but then, after they've done some more research on the water quality, they've decided to go elsewhere," she said.

Any assessment of Newport's economic aspirations must address the gaping hole in the middle of its downtown, where the promises of a four-story hotel and mixed-use project evaporated in the EB-5 foreign investors scandal, leaving only an empty pit where buildings had been demolished to make way for the project. Colorful artwork on fences now shields from view a vacant site that has so far defied efforts to lure development.

Signs of the city's potential, and its struggles, are everywhere. Several retail storefronts sit vacant even as a Thai restaurant and hot yoga studio bustle. Colorful petunias adorn downtown lampposts while weeds choke an adjacent sidewalk.

Converse said his group and DUMP haven't always seen eye to eye. While DUMP is committed to being a watchdog of the landfill, the association takes a broader view of lake health and doesn't believe the landfill is the primary threat; Converse points to excessive phosphorus.

But they agree that if Memphremagog's waters are fouled, Newport's fortunes will follow. While Converse thinks Casella is "doing as good a job as they can possibly" in managing the landfill, he agrees that people need to produce less waste and the state should stop sending it all to a single location on the shore of a vital waterway.

"We can't keep this up forever," he said.

Testing, Testing

In May, DUMP called on state Natural Resources Secretary Julie Moore to formally declare Memphremagog a "lake in crisis," like the much smaller Lake Carmi, where persistent, widespread cyanobacteria blooms fed by phosphorus from surrounding farmland are a perennial problem.

Such a designation could have focused greater attention and resources on lake cleanup efforts. More than 3,700 people signed a petition in favor. But Moore rejected the petition because it didn't meet all the criteria for the designation.

For the lake to qualify, property values around it would have to be declining due to the pollution. But home prices in Orleans County are up 24 percent compared to the same period last year, according to the Vermont Association of Realtors. That's a lower increase than in some parts of the state but still a clear sign of strong demand.

"We knew they weren't going to approve it, but this is a lake in crisis whether they want to acknowledge it or not," DUMP member Ladds said. She called it absurd that the state won't step in until the problem gets so bad that it negatively impacts property values.

Even though Memphremagog is "kind of the little sibling to Champlain" and therefore gets less funding and attention, the state still spent more than $500,000 on monitoring and cleanup work in the watershed last year, said Oliver Pierson, head of the state's Lakes and Ponds Management and Protection Program.

People are right to be concerned about the issues facing the lake, but that doesn't mean it's in crisis, he said. He noted that while there are occasional blue-green algae blooms, the water is more often uncommonly clear.

"I went boating and swimming in Memphremagog as recently as last summer and was in awe of the beauty and splendor of the place," Pierson said.

This summer, additional fish sampling is scheduled, according to Emerson, the fisheries biologist. Also planned: genetic analysis of the lesions on bullheads to determine possible causes, he said.

And later this summer, the first round of water-test results is to be released, at a public meeting in Newport. Moore will host the August 24 session to address lake health.

While it is understandable that people would look for links between the various threats facing the lake — high phosphorus, sick fish and chemical contaminants — Moore said she considers them separate issues and inquiries.

The tension between Vermont and Québec officials over the discovery of PFAS has largely been due to a lack of data to inform discussion about the problem, let alone identify the source — or sources — of the contamination.

Moore is hoping the collaborative sampling project will give scientists, policy makers and the public on both sides of the border a common understanding of the problem and lead to potential solutions.

"Not only do we not want to be polluting the lake," Moore told Seven Days, "we don't want our neighbors to the north to feel like we are."

Correction, August 22, 2021: Robert Benoit lives on Green Bay. A previous version of this story contained an error.

The original print version of this article was headlined "Beneath the Surface"

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

Tags: Environment, Lake Memphremagog, PFAS, Québec, landfill, Coventry Landfill

About The Author

Kevin McCallum

Bio:

Kevin McCallum is a political reporter at Seven Days, covering the Statehouse and state government. He previously was a reporter at The Press Democrat in Santa Rosa, Calif.

Kevin McCallum is a political reporter at Seven Days, covering the Statehouse and state government. He previously was a reporter at The Press Democrat in Santa Rosa, Calif.

More By This Author

Latest in Environment

Speaking of...

-

Québec’s Powwow Season, a Summer Tradition, Kicks Off

Jun 26, 2024 -

Chemicals Leaked From Guard Base Reached a SoBu Wastewater Plant

Jun 24, 2024 -

Montréal's Jewish Eateries Serve Classics From Around the World

Apr 9, 2024 -

Where to See the 2024 Solar Eclipse in Québec

Feb 26, 2024 -

Montréal’s McCord Stewart Museum Features a Groundbreaking Exhibit of Indigenous Art

Feb 7, 2024 - More »

find, follow, fan us: