Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

-

Education

Scott Official Pushes Back on Former State…

-

News

Burlington Budget Deficit Balloons to $13.1 Million

-

Education

Senate Committee Votes 3-2 to Recommend Saunders…

- Court Rejects Roxbury's Request to Block School Budget Vote Education 0

- Norwich University Names New President Education 0

- Media Note: Mitch Wertlieb Named Host of 'Vermont This Week' Health Care 0

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

Stickin' to His Guns? The NRA Helped Elect Bernie Sanders to Congress. Now He's Telling a Different Story.

Published June 26, 2019 at 10:00 a.m.

Four hours after a former city worker gunned down 12 people at the Virginia Beach Municipal Center last month, Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) took to Twitter to call for gun control.

"The days of the NRA controlling Congress and writing our gun laws must end," he wrote, referring to the National Rifle Association. "Congress must listen to the American people and pass gun safety legislation. This sickening gun violence must stop."

In a statement to the New York Times, Sanders spokesperson Arianna Jones said he would "continue pushing for policy that reflects the urgency of this national crisis, including his three-decades-old support for an assault weapons ban."

The response was classic Sanders. Central to his 2020 campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination is the notion that he has consistently supported the same policies — and opposed the same special interests — throughout his half century in public life.

But when it comes to gun rights, the senator from Vermont has been anything but consistent. During his first two decades in Congress, Sanders supported much of the NRA's legislative agenda. And according to many who witnessed his rise from political obscurity to the presidential debate stage, he owes his career to the very special interests he now denounces.

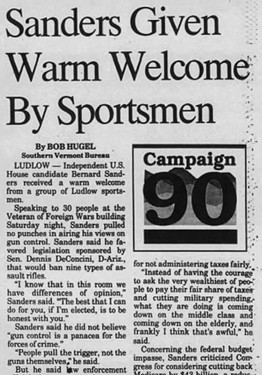

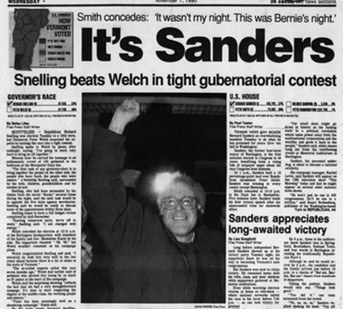

click to enlarge

- Rutland Herald

- An October 26, 1990, account of the NRA's efforts to defeat Peter Smith

Sanders was elected to the U.S. House in 1990 after his predecessor, Republican Peter Smith, embraced an assault weapons ban, earning the wrath of the NRA and an influx of money to defeat him.

"We don't like everything that Mr. Sanders has to say about firearms," NRA lobbyist James Baker told the Rutland Herald in October 1990 as the organization flooded the state with anti-Smith advertisements and mailings. "But he's been up front about it. He's at least as good, if not better, than Mr. Smith."

When Sanders first ran for president in 2016, Smith declined every interview request but one, from the Washington Post, and even then refused to discuss the 1990 race. "It was going to be very partisan, and I did not want to become the issue," he told Seven Days this month.

Now semiretired and living in Santa Fe, N.M., the 73-year-old ex-politico wants to make clear that, in his view, the NRA's involvement was "the predominant reason" Sanders defeated him nearly three decades ago.

"He would like to have the reason why he won the first race go away," Smith said of Sanders. "But it's a matter of public record."

Upon arriving in Congress in 1991, Sanders repeatedly voted against legislation requiring waiting periods for those buying firearms. He opposed a 1996 measure that would have allowed the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to fund research on gun violence. And he voted in favor of a 2005 law shielding gun manufacturers from lawsuits — a "historic victory" for the NRA, as the organization's executive vice president, Wayne LaPierre, called it at the time.

Sanders has since reversed course and now supports a raft of federal gun-control initiatives.

But for most of his career, Sanders argued that the states, not the federal government, should be charged with regulating firearms. During a failed 1988 bid for the U.S. House, Sanders publicly opposed mandatory waiting periods for gun buyers and told the Burlington Free Press he was satisfied with the nation's gun laws. "It's a local control issue," he said shortly before the '88 election. "In Vermont, it is not my view that the present law needs any changing."

Nearly 25 years later, in the wake of the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting in Newtown, Conn., Sanders made the same argument in an interview with Seven Days, much of which has not previously been published.

"My own view on guns is: Everything being equal, states should make those decisions," he said during the March 6, 2013, interview in his Capitol Hill office.

At that moment, Sanders seemed unwilling to commit to a series of new gun laws proposed by then-president Barack Obama and vice president Joe Biden, including an assault weapons ban.

"I don't think assault weapons—" Sanders began, cutting himself off. "Let me just say this about guns: You've got 300 million guns in this country. You've got 5 million assault weapons. If you passed the strongest gun-control legislation tomorrow, I don't think it will have a profound effect on the tragedies we have seen, which are really tragedy."

Listen to Paul Heintz's March 6, 2013 interview with Sanders about gun control in the wake of the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting.

Update Required To play the media you will need to either update your browser to a recent version or update your Flash plugin.

The next month, Sanders voted for the entire Obama/Biden package — including universal background checks, bans on assault weapons and high-capacity magazines, and tougher penalties for gun traffickers and straw purchasers — but the measures failed to pass the Senate. Ever since, Sanders has portrayed himself as a champion of gun control.

"Things really changed with the 2012 Newtown shooting," said Adam Winkler, a professor at UCLA School of Law who studies gun policy. "We've seen this go from being an issue that Democratic candidates avoided talking about to being one that they have to talk about."

As Sanders contends with a field of presidential rivals "falling all over themselves" to outdo one another on gun control, Winkler said, "it seems like some of his early votes are going to come back to haunt him."

More damaging still could be the perception that, when it comes to guns, Sanders is not the paragon of principle he's reputed to be. His inconsistency on the issue suggests that his position has been driven by the politics of the moment — an uncharacteristic aberration for Sanders.

"He doesn't really care about guns," his close friend Richard Sugarman, a University of Vermont professor, explained to the National Journal in 2014. "But he cares that other people care about guns. He thinks there's an elitism in the antigun movement."

Rather than acknowledge that his views have evolved over time, the Sanders campaign insists he's stayed the course for more than 30 years.

Sanders himself has repeatedly suggested that he lost his first race for the House in 1988 because he backed a ban on assault weapons, though there's little evidence that's the case. Media coverage of that campaign hardly mentions the issue. Nevertheless, his aides point to the episode as yet another example of his unwavering consistency.

"I think his fundamental view has been unchanged," Jeff Weaver, who worked as Sanders' campaign driver in 1988 and now serves as senior adviser to his presidential bid, said in a recent interview.

"The principles that he's operating on have been consistent. The context has changed," Weaver said, referring to the ever-worsening epidemic of mass shootings. "The understanding of the kind of problem that we're confronting has changed — and he has responded to that."

Mr. Smith Goes to Washington

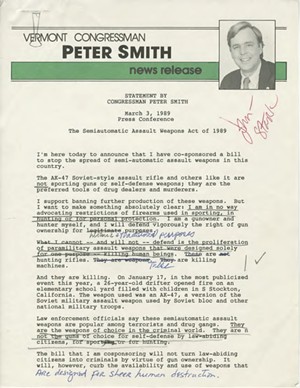

click to enlarge

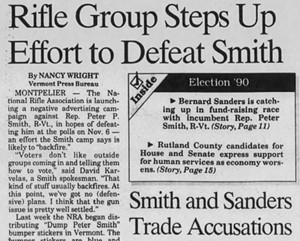

- Laura Patterson/cq Roll Call Via Ap Images

- Bernie Sanders and then-representative Peter Smith debating in Burlington on October 22, 1990

When Smith ran for Congress in 1988, the former lieutenant governor vowed to oppose any new gun laws — and won the NRA's endorsement. But two months after taking office, he returned to Montpelier in March 1989 to make a dramatic announcement: The 43-year-old Republican had changed his mind.

"I'm here today to announce that I have cosponsored a bill to stop the spread of semiautomatic assault weapons in this country," said Smith, a preppy alumnus of Princeton and Harvard universities who hailed from a family of bankers and politicians. On a table beside him sat his own Winchester 94 hunting rifle and an AK-47 that the Montpelier police chief had brought for the occasion.

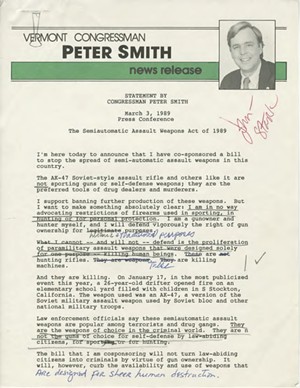

click to enlarge

- Vermont Historical Society

- Peter Smith's prepared remarks for a March 3, 1989 speech announcing his support for an assault weapons ban

Smith said he'd continue to support the use of firearms like his for hunting and self-protection. "What I cannot — and will not — defend is the proliferation of paramilitary assault weapons that were designed solely for one purpose: killing human beings," he said, referring to the AK-47 and nine other firearms the bill would ban. "These are not hunting rifles. These are killing machines."

Smith later attributed his change of heart to two events. That January, a white supremacist drifter had fatally shot five children and wounded 32 others at a Stockton, Calif., elementary school. And in February, Smith had met with a group of high school students from a crime-ridden neighborhood of Washington, D.C., who felt menaced by guns in their community.

"It was simply one of those moments," Smith said recently. "The next morning I was brushing my teeth, looking in the mirror, [and] I had this moment of, You're going to be looking at this face all your life, and you better like the person you're looking at."

According to Steve Terry, a former journalist and congressional aide, Smith had touched "the third rail" of Vermont politics. His turnaround represented "the first time that a prominent politician from Vermont has supported any type of national gun ban," the Barre-Montpelier Times Argus reported at the time.

"Vermont always had a live-and-let-live gun culture," former governor Howard Dean recently recalled. Dean, who was endorsed by the NRA in all eight statewide races he ran, said he couldn't recall a single piece of gun-control legislation that gained traction in the legislature during his time in office in the 1990s.

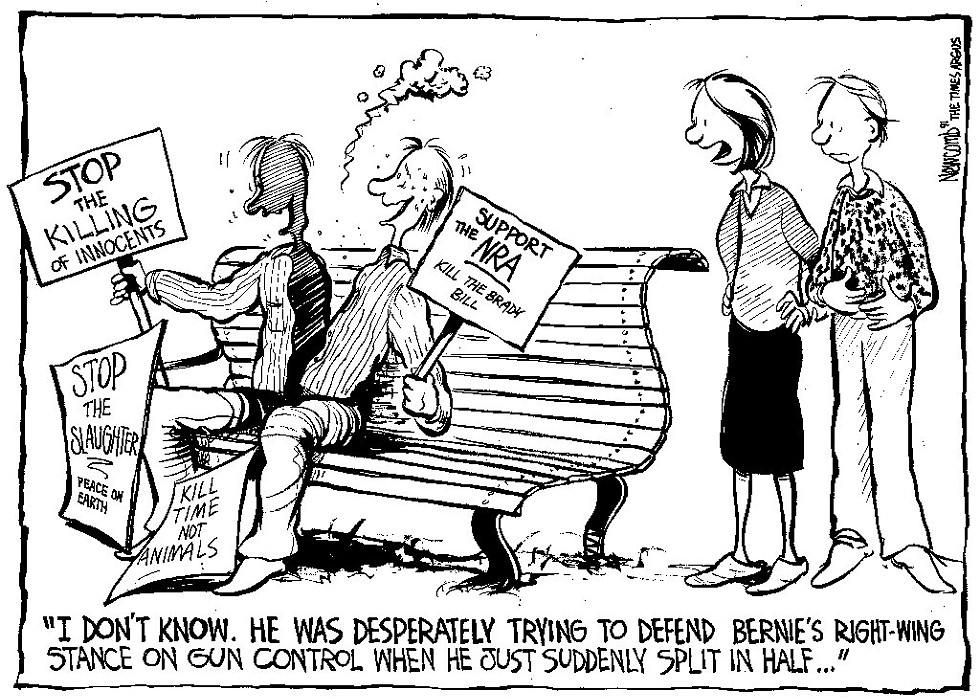

The reaction to Smith's shift was swift and fierce. Flyers circulated with his likeness beside a photo of Adolf Hitler. "WHICH MAN IS THE ORIGINATOR OF GUN CONTROL?" it asked. Another depicted Smith with a Pinocchio nose. The Sporting Alliance for Vermont's Environment called on him to resign. And, according to Smith, his family faced harassment and threats.

During a town meeting that December at Middlebury's Ilsley Public Library, Hinesburg resident Craig Cook told Smith, "The bill that you sponsored is taking away my freedom of choice and ... my culture."

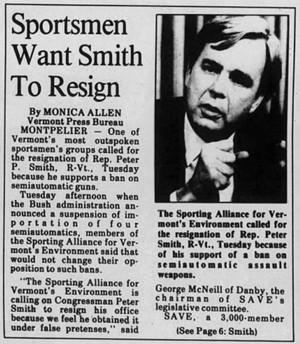

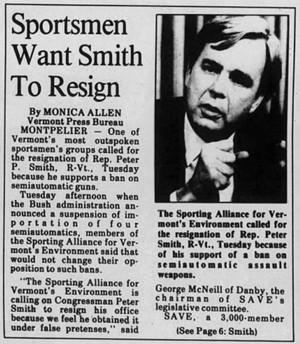

click to enlarge

- Rutland Herald

- A March 15, 1989, account of the backlash Smith faced after supporting an assault weapons ban

Richard Watts, then a rookie reporter for the Addison County Independent, covered the meeting and was taken aback by the hostility and anger Smith faced. "Maybe we're used to it today, but there used to be a little more civility at those things," said Watts, who now runs UVM's Center for Research on Vermont. "They felt they had been lied to."

The following March, leaders of 22 hunting and fishing clubs convened a meeting of the newly formed Vermont Sportsmen's Legislative Committee, according to the Vanguard Press. Nineteen of them indicated they would back Sanders, a former mayor of Burlington, if he challenged Smith in the 1990 election.

"The issue is credibility," explained Harry Montague, vice president of the Vermont Federation of Sportsmen's Clubs, adding that, with Sanders, "you know what you are going to get."

The former mayor of Burlington, an independent, had outperformed expectations when he'd run for the seat two years earlier, picking up nearly twice as many votes as Democratic nominee Paul Poirier and losing to Smith by just 3.7 percentage points. This time around, Sanders had reason to believe that the sporting community would have his back. Steven Rosenfeld, who served as his press secretary in 1990, later wrote a campaign tell-all called Making History in Vermont: The Election of a Socialist to Congress. In it, he recounted that in June 1990 Sanders had told him that the vice president of the Sporting Alliance for Vermont's Environment had pledged the group's support to him in the general election.

The issue came to a head later that month, when all five candidates running in the congressional primary took part in a debate hosted by the Vermont Federation of Sportsmen's Clubs, footage of which Seven Days obtained from the Vermont Historical Society. Sanders told his television audience that he had supported an assault weapons ban two years earlier — and he wouldn't change his tune when it was politically expedient.

"I said that before the election," he said in the debate.

Smith's Republican primary opponent, Timothy Philbin, was even less subtle. "When you run for office and you say something ... and do the opposite, that concerns [voters]," Philbin said, staring down Smith from across a crowded table. "That's not representation."

Sanders piled on, saying he agreed with Philbin. "The reason, I think, that this is as high as it is on the political agenda this campaign is not primarily about guns," he said. "I think it has something to do with credibility."

The exchange left Smith seething. "I would just look Tim Philbin and Bernie Sanders in the eye and say: What you are saying is absolute political garbage," he snapped at his opponents in the Williston television studio, pounding the table. "Now, Tim, I know you come from a long tradition, and you believe it. Bernie, I have to say, I respect you, but I am surprised to see you buying the national NRA strategy."

As the debate drew to a close, Smith defended his position as "common sense" and castigated the NRA. "First, they talked about guns. That didn't work, so they attacked my family. That didn't work, so they put up posters with me and Adolf Hitler. That didn't work, so they decided to go after the issue of credibility."

Then he took one last swing at Sanders. "In closing, I would say: Bernie, in the Free Press in 1988, you said gun control was a local issue," Smith said. "This is a federal issue. I'm delighted to see that you've come along..."

Watch Sanders, Smith and their rivals in Vermont’s 1990 U.S. House race debate in a Vermont Federation of Sportsmen’s Clubs forum.

As Sanders attempted to interrupt Smith, the moderator cut them both off and brought the debate to a close.

Later that day, Rosenfeld wrote in his book, Sanders called him to express unease about the role of firearms in the campaign. "It's an issue I do not feel comfortable about," he confided to his press secretary. "We want Mr. Philbin to do our dirty work for us."

'The Straw That Broke the Camel's Back'

How critical a role the NRA played in Sanders' election has been a matter of debate for decades. Though his advisers now downplay the organization's involvement, Sanders himself cited it as one of several reasons for his victory in his 1997 memoir, Outsider in the House.

"While the NRA has never endorsed me or given me a nickel, their efforts against Smith in 1988 clearly helped my candidacy," he wrote, adding that the group had "strongly" opposed him in subsequent elections.

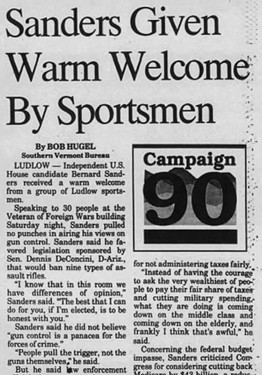

click to enlarge

- Rutland Herald

- An October 22, 1990, account of Bernie Sanders' visit to a gathering of sportsmen in Ludlow

The record shows that Sanders made the most of Smith's troubles. At a gathering of sportsmen in Ludlow just weeks before the election, he pledged "to be honest with you" if he made it to Congress. According to a Rutland Herald account of the event, he told his audience that he did not believe "gun control is a panacea for the forces of crime."

"People pull the trigger, not the guns themselves," Sanders added.

In the closing weeks of the campaign, the NRA distributed thousands of "Dump Peter Smith" bumper stickers, according to the Herald, and spent tens of thousands of dollars on advertisements and mailings.

Sanders apparently knew the onslaught was coming. According to Rosenfeld's memoir, gun-rights activist John McShane faxed the campaign a copy of the bumper sticker with a handwritten note that read, "10,000 by hand, 13,682 by mail this week." Sanders met with McShane that evening at the latter's home in Poultney, Rosenfeld wrote.

In one letter to voters obtained by the Washington Post, LaPierre of the NRA wrote, "Bernie Sanders is a more honorable choice for Vermont sportsmen than Peter Smith." Baker, the NRA lobbyist, told the Herald in October that his organization was even considering donating directly to Sanders' campaign.

At a subsequent press conference, Sanders said he wouldn't take the money, if offered. "Bernie Sanders did not receive the endorsement of the NRA, Bernie Sanders has not asked for the endorsement of the NRA, Bernie Sanders does not want the endorsement of the NRA," he said of himself.

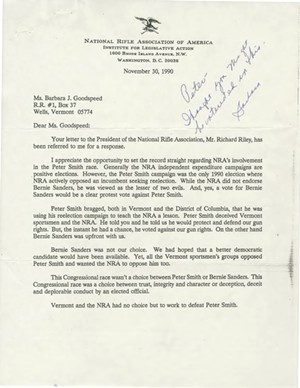

click to enlarge

- Vermont Historical Society

- A November 30, 1990, letter from NRA lobbyist Mary Kaaren Jolly explaining the organization's support for Sanders

But in a postelection letter to an aggravated Vermonter, NRA lobbyist Mary Kaaren Jolly confirmed that the organization had worked to elect Sanders — if only to defeat Smith. "While the NRA did not endorse Bernie Sanders, he was viewed as the lesser of two evils," she wrote in the letter, which is preserved in the Smith archives at the Vermont Historical Society. "And, yes, a vote for Bernie Sanders would be a clear protest vote against Peter Smith."

In the end, it wasn't even close. Sanders swept the 1990 election with 56 percent of the vote, while Smith claimed 39.5 percent, and Democrat Dolores Sandoval took just 3 percent. It was the only time since Robert Stafford defeated William Meyer in 1960 that an incumbent member of Congress from Vermont lost reelection.

In an interview the next day, Smith blamed his defeat on the late push by the NRA. "It hurt in a way that I can't even begin to calculate," he said. "That played a significant role in the outcome of this election. Nobody really noticed it."

The NRA did not respond to Seven Days' requests for comment.

Few elections are won and lost on a single issue — and Smith faced plenty of other setbacks. As Rosenfeld put it in a recent interview, "I think the gun issue was the first domino, but there were other dominoes."

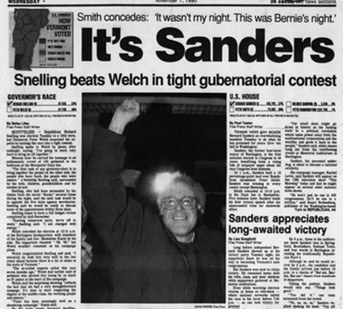

click to enlarge

- Burlington Free Press

- A November 7, 1990, account of Sanders' victory over Smith in Vermont's race for the U.S. House

Among them was Smith's support for a deficit-reduction bill that would have made deep cuts to Medicare and Medicaid. That provided an easy opening for Sanders, an irascible outsider, to make the case that Smith, the consummate establishment man, didn't care about the elderly and the poor.

Other causes included the dearth of a credible Democratic candidate — Sandoval, a UVM professor, was best known for supporting the legalization of all drugs — and the unusual length of the 1990 congressional session, which kept Smith off the campaign trail late into the fall. When then-president George H.W. Bush traveled to Burlington to stump for him, Smith caused a stir by publicly criticizing his guest for refusing to raise taxes on the wealthy.

Trailing in the polls by late October, Smith released a negative TV ad linking Sanders, a self-described socialist, to Cuban president Fidel Castro and suggesting that Sanders had been "nauseated" by president John F. Kennedy's inaugural address. "Peter Smith's support after that ad collapsed," Weaver recalled.

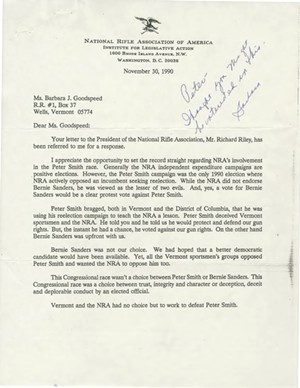

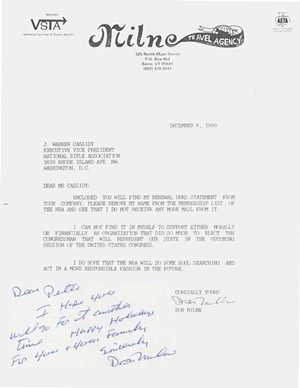

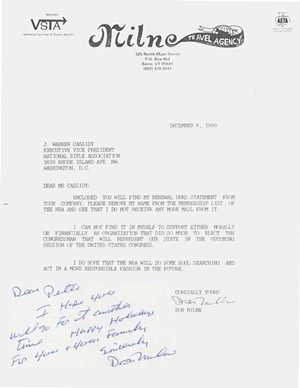

click to enlarge

- Vermont Historical Society

- Don Milne wrote the NRA on December 6, 1990, to cancel his membership over its support for Bernie Sanders — and then sent a copy of the letter to Peter Smith

According to Terry, the longtime observer of Vermont politics, all those issues contributed to Sanders' victory, but it was Smith's gun flip-flop that did in the incumbent.

"It was the straw that broke the camel's back," he said.

"That's sort of why Bernie got elected," confirmed state Sen. Anthony Pollina (P/D-Washington), who volunteered on the Sanders campaign and went to work for him the next year.

Condolence cards flooded in after Smith was defeated — and many of them mentioned the NRA's role. Don Milne, a travel agent who would soon become clerk of the Vermont House, sent Smith a copy of a letter he'd written to the NRA canceling his membership.

"I can not find it in myself to support either morally or financially an organization that did so much to elect the congressman that will represent our state in the upcoming session of the United States Congress," Milne wrote in a letter now housed in the Vermont Historical Society collection. "I do hope that the NRA will do some soul searching and act in a more responsible fashion in the future."

The Other Foot

Sanders had been in Congress for less than a year when he found himself responding to an act of gun violence — in his home state.

On October 25, 1991, a 30-year-old engineer named Elizabeth Teague brought a semiautomatic handgun to work at the Eveready Battery factory in Bennington, where she fatally shot 47-year-old plant manager Jonathan Perryman and wounded three other coworkers. Before fleeing the building, she set off several crude explosive devices consisting of gunpowder and gasoline.

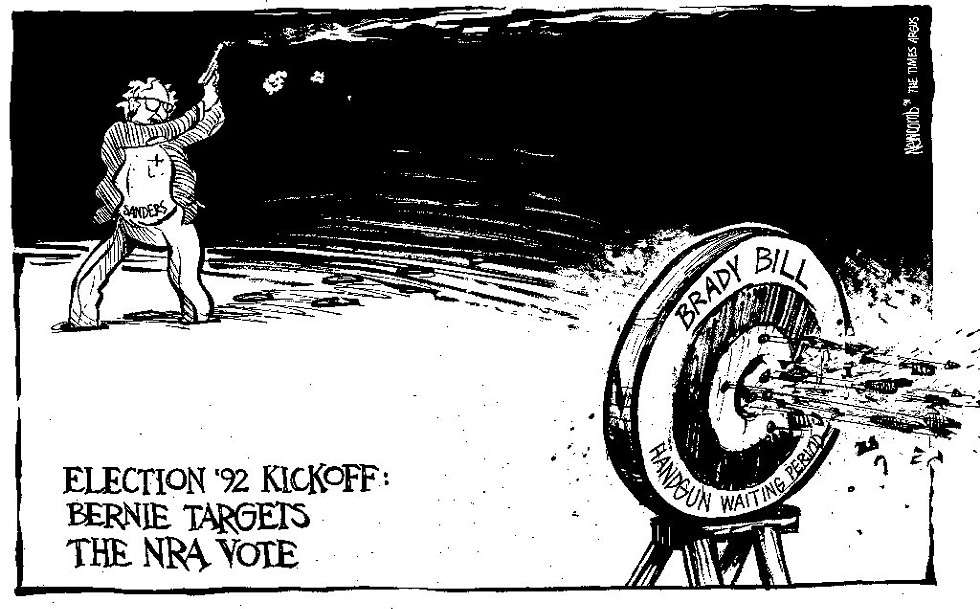

When Sanders traveled to Bennington two days later to address a labor forum, he couldn't escape questions about his vote earlier that year against the so-called Brady Bill, which required a seven-day waiting period for all handgun purchases, enabling states and localities to perform criminal background checks in the interim. In an interview following the forum, the first-term House member called the bloodshed in Bennington "tragic" — but he argued that the legislation would have done nothing to prevent it. The solution, he said, was to lift people out of poverty.

click to enlarge

- Rutland Herald

- An October 28, 1991, account of Bernie Sanders' visit to Bennington following a shooting at the Eveready Battery plant

"Anyone who has any illusions that gun control will cause a significant dent in the very serious problem of crime is mistaken," Sanders told the Herald.

It was the first of many such uncomfortable interviews for Sanders, who for the next two decades would often have to account for his voting record when another mass shooter struck.

Five months before the Bennington killing, when he cast his first vote against the Brady Bill, Sanders made the case that waiting periods and background checks were best left to the states.

"If it's wanted in the legislature, let it be dealt with in the legislature," he told the Associated Press, adding, "Vermont and Wyoming are very different types of states than California or New York State." An aide, Doug Boucher, told the Washington Post that more Vermonters had been killed that year by knives than by guns — an assertion the Vermont Crime Information Center quickly debunked.

The Vermont Times offered another explanation for Sanders' vote in a story unsubtly headlined, "Who's Afraid of the NRA? Vermont's Congressmen, That's Who." Pollina, then serving as Sanders' state director, rebutted the premise of the piece, noting that his boss disagreed with the NRA over assault weapons.

"[H]e doesn't just represent liberals and progressives. He was sent to Washington to represent all Vermonters," Pollina told the paper. "It's not inappropriate for a congressman to support a majority position, particularly on something that Vermonters have been very clear about."

The state's newspaper editorial boards apparently disagreed. The Free Press wrote that Sanders had offered "limp excuses" for his vote, while the Herald called his position "opportunistic."

"Sanders is dead right when he says the cure for rampant violence lies in economic justice, education and law enforcement," the Times Argus editorialized. "But he's dead wrong in writing off the measure as useless. Until Americans can achieve that more just, less desperate society, a measure that can help keep guns out of the wrong hands is vital."

When the Washington Post profiled him in the summer of 1991, Sanders sounded exasperated by the notion that he had "caved to the NRA."

"I have a problem with a Congress and media that spend an enormous amount of time talking about the Brady [B]ill, which even the strongest proponents know will not have a major impact on crime," he said. "I view it as hypocritical."

Sanders voted against the Brady Bill three more times before it finally became law in 1993. That year, he backed an alternative proposal that would have replaced the waiting period with an instant criminal background check — evidence, in Weaver's telling, that Sanders supported gun control even then. But the Washington Post called such claims "misleading," noting that the NRA was behind the plan and that it would have effectively gutted the Brady Bill because "the technology for such an instant check did not exist."

The following May, Sanders finally backed a bill the NRA opposed: an assault weapons ban similar to the one that had been his predecessor's undoing. The measure was later folded into a comprehensive crime bill that instituted a three-strikes policy for violent criminals, expanded use of the death penalty, and funded the hiring of new police officers and the building of new prisons. Sanders backed that, too.

click to enlarge

- Burlington Free Press

- An August 26, 1994, account of the backlash Sanders faced after supporting an assault weapons ban

Sanders' support of the ban infuriated some of the same people who'd brought him to power. That August, the Vermont Sportsmen's Coalition launched a "Bye-Bye Bernie" campaign, according to the Free Press. Its leaders promised to do to Sanders what they'd done to Smith four years earlier.

"He lied to us ... He told us gun control should be debated at the state level," the group's spokesperson, Douglas Hoffman, said. "There was a bill to ban semiautomatic weapons in the Vermont legislature this year, and it lost. But Bernie voted for the same thing in Congress."

Sanders called that reasoning "torturous" and noted that he had consistently supported an assault weapons ban since 1988. "[I]t would be dishonest for anyone to suggest that I have been less than honest or straightforward about my stand," he said.

In that fall's campaign, for the first time, Sanders leaned in to his support for gun control, buying a print advertisement hailing his "courage" for getting assault weapons "off our streets."

"Bernie Sanders stood up to the National Rifle Association and other powerful interests and voted for the ban," the ad said.

That November, Sanders defeated Republican state senator John Carroll by 3.3 percent, the closest race of his congressional career.

'Never Faltered'

In the years following Sanders' vote for the assault weapons ban, his record on gun legislation was decidedly mixed, according to a tally kept by PolitiFact.

At times, he crossed the NRA, such as when he voted for a three-day waiting period for firearms purchased at gun shows and when he opposed a measure that would have limited the use of trigger locks. At times, he continued to support its agenda, such as when he opposed funding for gun violence research and backed NRA initiatives to allow firearms in national parks and on Amtrak trains.

The votes that would cause him the most political grief would be those, in 2003 and 2005, for the Protection of Lawful Commerce in Arms Act, which prohibited lawsuits against gun manufacturers and retailers for the unlawful misuse of firearms.

That position appeared at odds with Sanders' history of "railing at corporate interests," Valley News political columnist John Gregg wrote in December 2005. It represented a "'tragic capitulation to the special interest gun lobby,'" he quoted Michael Barnes, president of the Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence, as saying.

Sanders' explanation? "He agrees with the proposition that if gunmakers follow all the federal rules ... and someone goes and buys the gun and does something illegal with it, [the firearms industry] should not be held responsible for it," Weaver, then Sanders' chief of staff, told the Valley News at the time.

Eliot Nelson, a retired pediatrician and early Vermont gun-control advocate, said he was flummoxed by the move.

"I was appalled that anybody would think that the gun industry should enjoy immunity for making and selling and marketing a product whose primary purpose is to kill and intimidate," the South Burlington resident said. He said he wrote to Sanders to express that view but never heard back.

Ready, Aim, Fire: A Timeline of Sanders' Stands on Gun Control

As the frequency of mass shootings in America grew, Sanders stuck to his view that, generally speaking, the federal government should steer clear of gun policy. Guns were a problem in New York City and Chicago, he would argue, but not in Vermont.

Those who study the issue say that's not the case. Though Vermont has a low homicide rate, it has higher than average suicide and gun-related domestic violence fatality rates.

"We have a gun violence problem," said UVM pediatric critical care physician Rebecca Bell. "And it is problematic when policy makers gloss over that."

Ironically, the very people whose support Sanders was courting with his position on guns — white, rural men — were the ones most at risk, according to Bell. "These are the people who are really hurting in this state," she said.

In August 2012, after a gunman killed 12 people and wounded 58 at a movie theater in Aurora, Colo., Sanders told the Addison County Independent that "decisions about gun control should be made as close to home as possible — at the state level."

The parents of one Aurora victim, Jessica Redfield Ghawi, later sued the online businesses that had sold the gunman ammunition and body armor. But because the Protection of Lawful Commerce in Arms Act barred such suits, a federal judge threw it out and forced Ghawi's parents, Lonnie and Sandy Phillips, to pay the companies' $203,000 attorneys' fees.

"I would like Bernie Sanders to at least apologize to us for the heartache this has caused," Lonnie Phillips told USA Today during the senator's 2016 presidential campaign.

It wasn't until a gunman killed 20 young children and six adults at Sandy Hook Elementary School in December 2012 that Sanders fully embraced federal gun laws — and, even then, not immediately.

For nearly three months after the shooting, the senator avoided interviews on the subject and refused to speak with Seven Days. When he finally sat down with this reporter the following March, he sounded skeptical of the Obama/Biden gun-control proposals. Those would have, among other things, expanded the use of background checks and restored the assault weapons ban, which had expired in 2004.

Though Sanders had said in a written statement in January that he was "certainly prepared" to back another assault weapons ban, he seemed to throw cold water on the idea in the March interview. "I suspect the ban on assault weapons is not going to go very, very far," he said. "But we'll be looking."

If it did reach the floor of the Senate, would he vote for it?

"We'll see," he responded. "We'll see to what other things it is part of. But I did vote for that ban in '94."

When Seven Days sought to clarify why, then, he'd express uncertainty about the measure, Sanders interrupted, pointed to a sheet of paper with a list of accomplishments and tried to redirect the interview to the economy.

"This is not one of my major issues," he said. "It's an issue out there. I've told you how I feel about it. If there's anything else you want to ask me about, I'm happy to answer. But that's about it."

Ultimately, Sanders did vote for each element of the Obama/Biden plan in April 2013, including the assault weapons ban. According to Jones, his current presidential campaign spokesperson, he hadn't considered doing otherwise.

"He has, in fact, never faltered in his support for the assault weapons ban," she wrote in an email.

Sanders, who has not granted Seven Days an interview since April 2015, did not respond to numerous requests for comment for this story.

Rearview Mirror

As he battled Hillary Clinton for the 2016 Democratic presidential nomination, Sanders struggled to explain his past support for the NRA's agenda — particularly his vote to grant immunity to the firearms industry.

Though Weaver had argued a decade earlier that it was a matter of fairness to gun manufacturers, Sanders sought to recast his vote as support for small Vermont gun shops. The candidate later claimed he'd backed the immunity bill in 2005 because it included restrictions on armor-piercing bullets and support for gun locks, but the Brady Campaign pointed out that the 2003 version, which he'd also supported, included neither provision.

After defending the law for months, Sanders announced in January 2016, days before the Iowa caucuses, that he'd cosponsor legislation repealing it. Two months later, at a debate in Flint, Mich., he backtracked and defended the immunity law again — drawing praise from the NRA.

"Sen. Sanders was spot-on in his comments about gun manufacturer liability/PLCAA," the organization wrote on Twitter, referring to the Protection of Lawful Commerce in Arms Act.

The explanation for Sanders' immunity vote continues to evolve. "I think it's pretty clear that the courts have interpreted that law much more broadly than certainly Bernie was comfortable with," Weaver recently told Seven Days. He said his boss had reversed course on only one other gun-related position: CDC funding for gun violence research, which he now supports.

Four years after Clinton attacked him from the left on gun control, Sanders is taking a different approach to the issue. Rather than simply defending past votes, he is voicing full-throated support for gun control.

"I'm running for president because we must end the epidemic of gun violence in this country," he said in his February 2019 campaign announcement. "We need to take on the NRA, expand background checks, end the gun show loophole, and ban the sale and distribution of assault weapons."

With 24 people competing for the Democratic nomination, "Every candidate wants to be distinctive in some way to differentiate themselves from the others," according to Robert Spitzer, a professor at the State University of New York Cortland and an expert on gun politics. "The gun issue is really tailor-made for that."

Already, Sen. Kamala Harris (D-Calif.) has proposed a series of executive actions to crack down on the gun industry, while Sen. Cory Booker (D-N.J.) has said he'd pursue a federal gun-licensing program.

But Spitzer is skeptical that Sanders' gun record will rob him of the nomination, saying it's "just not a top-tier issue."

Nearly 30 years after Smith's loss launched Sanders' congressional career, the ex-politician is trying not to focus on his former adversary's unexpected star turn. "I wouldn't deny that, from time to time, it sort of bugs me," Smith conceded.

Though he hasn't lived his life "in the rearview mirror," Smith said, he learns of each new episode of gun violence with a heavy heart.

"It makes me sorry I failed," he said.

But, Smith continued, "You pick a fight, and that's what I did. I chose a fight, and I lost."

The original print version of this article was headlined "Stickin' to His Guns? | Bernie's relationship with the NRA: It's complicated"

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

About The Author

Paul Heintz

Bio:

Paul Heintz was part of the Seven Days news team from 2012 to 2020. He served as political editor and wrote the "Fair Game" political column before becoming a staff writer.

Paul Heintz was part of the Seven Days news team from 2012 to 2020. He served as political editor and wrote the "Fair Game" political column before becoming a staff writer.

More By This Author

Latest in Category

Speaking of...

-

Vermont Awarded $62 Million in Federal Solar Incentives

Apr 22, 2024 -

Man Charged With Arson at Bernie Sanders' Burlington Office

Apr 7, 2024 -

Police Search for Man Who Set Fire at Sen. Bernie Sanders' Burlington Office

Apr 5, 2024 -

Bernie Sanders Sits Down With 'Seven Days' to Talk About Aging Vermont

Apr 3, 2024 -

Gun Group Sues Over Vermont's New Waiting-Period Law

Dec 18, 2023 - More »

find, follow, fan us: