Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

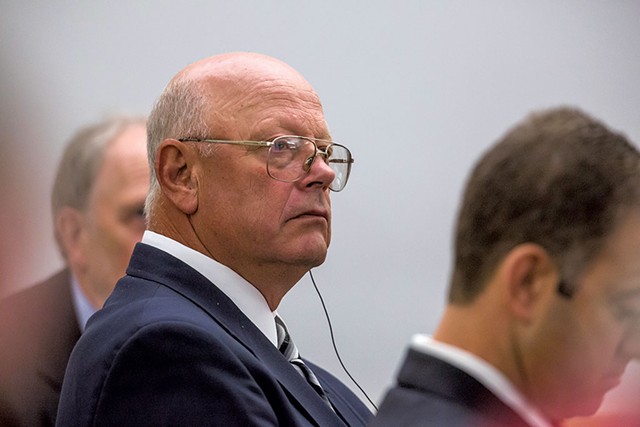

Trial and Error: What Went Wrong in the McAllister Case

Published June 22, 2016 at 10:00 a.m.

Hours after state prosecutors dropped the felony sexual assault charges against him, Sen. Norm McAllister (R-Franklin) was back on his farm in Highgate. He'd changed out of his courtroom blazer and tie into a T-shirt and shorts.

But there was no backyard victory party attended by high-fiving friends. Neither side was celebrating after the high-profile case reached its surprising conclusion last Thursday. Those who expected that the trial would bring clarity walked away without knowing whether McAllister — whose colleagues voted to suspend him from the Senate — was guilty or innocent of the charges against him.

As one of the 12 jurors confided to a reporter after the one-day trial: "I was just so confused."

On Wednesday, McAllister's accuser — a young woman who had worked for him first as a farmhand and then as a legislative assistant in Montpelier — took the stand and described where and how the senator repeatedly assaulted her. Her testimony was expected to continue into Thursday, but instead, Franklin County Deputy State's Attorney Diane Wheeler started the second day of the trial by dismissing the charges.

Does that mean there had been no sexual contact between the 64-year-old legislator and the woman, who is now 21? "I'm not going to answer that," McAllister's defense attorney, Brooks McArthur, said outside the courthouse. A second sexual assault case still hangs over the senator, and that trial has not been scheduled. McAllister is running for reelection without having definitively cleared his name.

As for the accuser, she left the courthouse disappointed, upset and regretting that she ever got involved in the case, according to her Burlington lawyer, Karen Shingler. She said the young woman stands by her allegations against McAllister.

So what went wrong?

The accuser's four-hour testimony was hardly a slam dunk. Clearly anxious, uncertain and occasionally defiant, she struggled to answer even simple questions, such as how long it took her to drive from her home to McAllister's farm. When Wheeler — the lawyer on her side, who's been prosecuting sex crimes for two decades — asked how long it took her to do the farm chores, she said she didn't know.

But that's not what led to the dismissal, said Shingler, who represented the accuser at the request of the Franklin County State's Attorney's Office.

Last Thursday morning, Wheeler said that new information she received the night before made her ethically obligated to dismiss the charges.

Franklin County State's Attorney Jim Hughes said his office could not reveal what the new information was. "I can't tell you specifics or details of the ethical dilemma, because we still have charges pending against Mr. McAllister," he said.

Shingler was more forthcoming. "She lied under oath and admitted it," the lawyer said of her client. She said that after last Wednesday's proceedings, the young woman admitted that she had answered one tangential question untruthfully.

Wheeler later confirmed that the statement "did not directly relate to the allegations that Norman McAllister repeatedly sexually assaulted her." She said her office had no plans to pursue perjury charges.

Such a revelation does not necessarily have to halt a trial, according to lawyers not involved in the case. A prosecutor could reveal the information to the defense and the judge and continue with the case, said Tristram Coffin, a former federal prosecutor in Vermont.

Instead, Shingler said she advised her client not to continue testifying unless Wheeler granted her immunity from prosecution for perjury, which Wheeler declined to do.

Shingler said that while her client admitted to a misstatement, she stood by her claim that McAllister sexually assaulted her multiple times in his house, in an old barn and at his apartment in Montpelier.

It's not uncommon for an accuser to tell a lie that is tangential to the case while on the stand, said Anne Munch, a former prosecutor who is a Denver-based consultant on sexual assault and domestic violence. It doesn't mean the whole story was fabricated, she said. The challenge for a prosecutor, she said, is to prepare the jury for potentially problematic testimony.

"Human beings sometimes tell lies. Any human being has a difficult time remembering things exactly as they happened," Munch said.

But the case against McAllister looked to be floundering even before the alleged mistruth surfaced. There was no physical evidence against the defendant, and McAllister's attorneys had earlier won a bid to sever two sexual assault cases into two trials, meaning that the jury last week would never have heard that another woman had also accused McAllister of sexual assault.

That put all the pressure on McAllister's 4-foot-11-inch accuser, who was dressed in jeans and a plaid button-down shirt with her hair pulled back in a ponytail. Wheeler described her in a pretrial court hearing as a "simple girl."

In his cross-examination, David Williams, one of McAllister's two defense attorneys, spent hours Wednesday afternoon poking holes in her story. He confronted the witness with audio clips of interviews she'd given under oath in early depositions that conflicted with her testimony that day.

For example, she initially alleged that McAllister sexually assaulted her on her first day of work at his farm. But in court, Williams pointed out, she testified that the first assault happened several weeks into the job. The accuser offered no explanation for the different stories.

The confused juror, who spoke to Seven Days on condition of anonymity, said he found her "not believable because she kept changing her story." He said he expected that during the second day of trial the discrepancies would be cleared up — but that day never came.

Shingler said her client was woefully unprepared for the courtroom. "She was a very young, unsophisticated woman facing a seasoned and experienced counsel. It wasn't an even match," Shingler said.

Experts say coaching the accuser is key to winning difficult sexual assault cases. A prosecutor should meet with her several times, conduct mock cross-examinations and take the person to court in advance, according to John Wilkinson, a former Virginia prosecutor who works as an adviser to Washington, D.C.-based AEquitas: The Prosecutors' Resource on Violence Against Women.

"You do have to really work with the victim in prepping them for trial," said Wilkinson, who called sex crimes the toughest type of cases to prosecute. "It's very, very stressful to have to get on the stand and recall the details," he said.

Jurors also need to expect uneven testimony from trauma victims — and understand it doesn't necessarily mean they are lying, Wilkinson said.

"You've got to educate them about that," he said. That can include bringing in a trauma expert to testify before the jury ever hears from the victim, he said.

Munch said she spoke at a Vermont training for legal professionals earlier this month about the importance of understanding the impact of trauma on victims.

"If the abuse is ongoing or where there is a real power differential, they're afraid; they're trying to figure out how to cope," she said. "They might not be paying attention to things we might think of, such as what day it happened."

Wheeler told the jury in her opening argument that the accuser silently hoped the assaults would end. Under questioning from Wheeler, the woman confirmed that she struggles with dates and times. But Wheeler offered the jury no information about scientific research on trauma victims.

Nor did prosecutors ask a trauma expert to testify. Hughes said they had planned to have state police detectives explain the accuser's behavior.

Jurors also never heard testimony about the reluctance of sexual assault victims to come forward and report the crimes perpetrated against them. Most victims just put it out of their minds, Munch said.McAllister's accuser alleged multiple assaults over several years but never told anyone about it. "If all this bothered her so much, why wouldn't she report it?" asked the juror.

The young woman never did go to police with her story — they came to her last spring while investigating other allegations against McAllister.

Lawyers on both sides said last week that the dismissal of this case could affect the next one, in which McAllister is accused of demanding sex from another farmhand in exchange for rent. There's more evidence against him. McAllister acknowledged in a taped conversation that he forced the accuser to perform sex acts she didn't want to, according to a police affidavit.

At his farmhouse on Thursday afternoon, McAllister said that he wanted to talk about what had just happened but wouldn't, because it won't "come out the way I said it." Following his lawyers' advice, the husky widower had refrained from talking to the media during the trial, too.

"It's not like me not to comment," he said. "I can't say what I want to."

Related Stories

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

More By This Author

About The Author

Terri Hallenbeck

Bio:

Terri Hallenbeck was a Seven Days staff writer covering politics, the Legislature and state issues from 2014 to 2017.

Terri Hallenbeck was a Seven Days staff writer covering politics, the Legislature and state issues from 2014 to 2017.

Speaking of...

-

Lawsuit Accuses Burlington Police of Using Excessive Force on Black Teen With Disabilities

Jan 31, 2024 -

Burlington Council Moves to Declare the Drug Crisis a Top Priority

Sep 7, 2023 -

The Acting Chief: For Three Years, Jon Murad Has Auditioned to Be Burlington's Top Cop. Will He Finally Get the Role?

May 3, 2023 -

National Law Enforcement Experts Come to Burlington to Share Ideas on Police Reform

Feb 20, 2023 -

Northfield’s Police Chief Takes Flak for His Provocative Public Stances

Feb 15, 2023 - More »

Comments (3)

Showing 1-3 of 3

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.

- 1. UVM, Middlebury College Students Set Up Encampments to Protest War in Gaza News

- 2. A Former MMA Fighter Runs a Wildlife Rehabilitation Center in Cabot News

- 3. Scott Official Pushes Back on Former State Board of Ed Chair's Testimony Education

- 4. Dog Hiking Challenge Pushes Humans to Explore Vermont With Their Pups True 802

- 5. Burlington Budget Deficit Balloons to $13.1 Million News

- 6. Senate Committee Votes 3-2 to Recommend Saunders as Education Secretary Education

- 7. Home Is Where the Target Is: Suburban SoBu Builds a Downtown Neighborhood Real Estate

- 1. Totally Transfixed: A Rare Eclipse on a Bluebird Day Dazzled Crowds in Northern Vermont 2024 Solar Eclipse

- 2. Zoie Saunders, Gov. Scott’s Pick for Education Secretary, Faces Questions About Her Qualifications Education

- 3. Don't Trash Those Solar Eclipse Glasses! Groups Collect Them to Be Reused 2024 Solar Eclipse

- 4. State Will Build Secure Juvenile Treatment Center in Vergennes News

- 5. Vermont Awarded $62 Million in Federal Solar Incentives News

- 6. Queen of the City: Mulvaney-Stanak Sworn In as Burlington Mayor News

- 7. New Jersey Earthquake Is Felt in Vermont News