Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

-

Education

Scott Official Pushes Back on Former State…

-

News

Burlington Budget Deficit Balloons to $13.1 Million

-

Education

Senate Committee Votes 3-2 to Recommend Saunders…

- Court Rejects Roxbury's Request to Block School Budget Vote Education 0

- Norwich University Names New President Education 0

- Media Note: Mitch Wertlieb Named Host of 'Vermont This Week' Health Care 0

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

Published December 13, 2017 at 10:00 a.m.

The street-level entrance to the Turning Point Center of Chittenden County looks a little sketchy. Though the cheery signs outside the door at 191 Bank Street in downtown Burlington announce it's "a safe and supportive environment for those in recovery" and "open every day of the year!" there's no missing the warning from the Vermont Department of Health.

"If you are using heroin," the state-sanctioned poster cautions, "it could be stronger than you think."

The warning refers to fentanyl, a narcotic 50 times more potent than heroin that is often mixed in with the drug. The results are sometimes deadly.

"If you are using," the sign pleads, "call to get help."

Alternately, addicts can head upstairs to Turning Point, a refuge for ordinary Vermonters who are trying to find their way out of drug dependence.

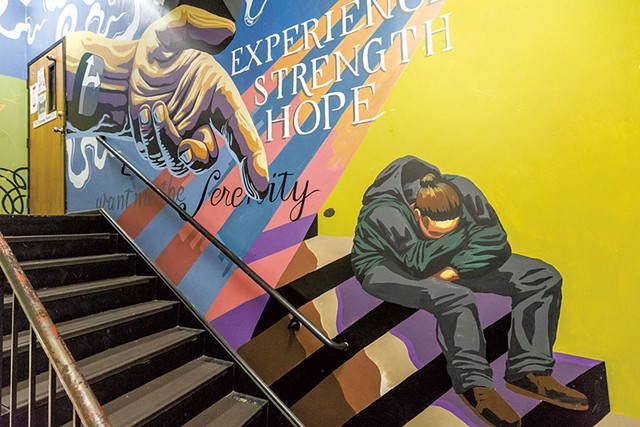

In the stairwell, a mural depicts a giant hand reaching down to a solitary slouching figure. Just outside the Turning Point door at the top of the stairs, another message, written in elegant gold script, reads: "You are no longer alone."

On Thanksgiving morning, a group of 20 or so people sat at tables in the windowless common room that had been decorated for the holiday with lights, handmade ornaments and colorful gourds. They talked, read books from the center's library or texted on their phones. Occasionally, someone strummed one of the center's two acoustic guitars.

The crowd that morning included volunteers and staff, as well as other visitors in recovery; to emphasize the dignity of those suffering from addiction, Turning Point refers to all of its visitors as "guests." These individuals may have been sober for a few hours or a few decades.

click to enlarge

- Oliver Parini

- Turning Point Center staff, left to right: Kelly Breeyear, Sara Glasgow, Ken Johnson and Gary De Carolis

When it opened in 2005, Turning Point mainly served members of Alcoholics Anonymous. A recent survey of its clientele found that their No. 1 "drug of choice," as it's called in the recovery community, was still booze. No. 2 was heroin.

The center doesn't endorse any one path toward getting clean and sober. Recognizing that different methods work for different people, it offers access to as many as possible. Sometimes, guests just need a warm place to socialize with sober friends and use the Wi-Fi, where they know they won't be triggered to relapse.

Holidays can be particularly challenging.

"Happy Thanksgiving!" staffer Sara Glasgow exclaimed as she burst through the door carrying two bags full of goodies.

Glasgow, 49, has been sober two and a half years. Like nearly all of the peer-run center's staff and volunteers, she's in recovery herself; the first time she walked through the door, in July 2015, she came to ask for help getting into detox. Glasgow's short gray hair, black jeans, black hoodie and paint-spattered Doc Martens suggest she's a cynical, old-school punk Gen-Xer — a little too cool for school. In fact, she's an earnest cheerleader for Turning Point and its guests.

That morning, Glasgow was flushed not from alcohol but from the cold and the exertion of climbing the stairs. She held up her bags. "This is my way of saying thank you," she said, "for letting me be here and be part of your recovery."

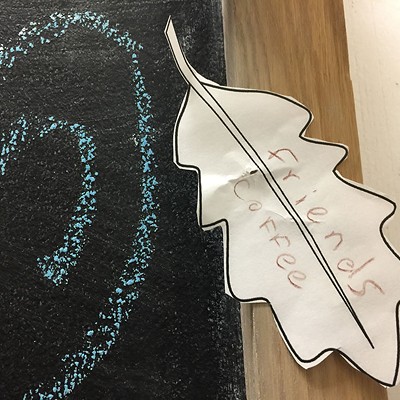

Glasgow brought her offerings to the common room's kitchen area and laid out a buffet of snacks on the counter, near the ever-present coffee maker and mugs. When the center is open, free coffee is always available.

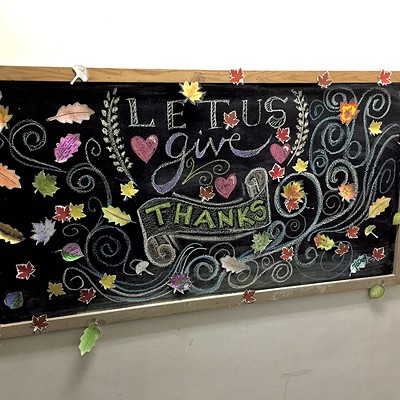

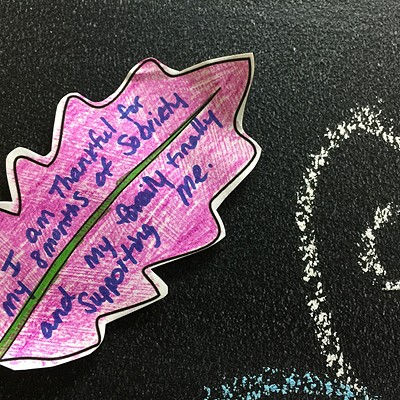

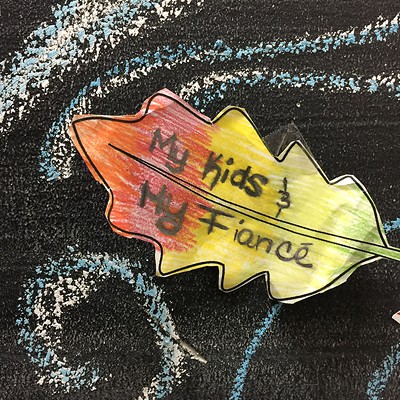

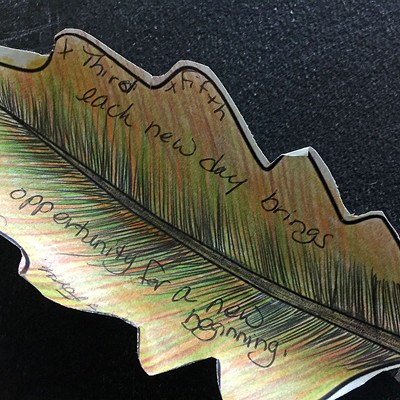

Glasgow is the paid manager on nights and weekends and also the center's creative director. The festive chalkboard in the stairwell was her idea. She used white, green, blue and red chalk to write: "Let us give thanks," adding a few pink hearts around the words and blue swirls to represent gusts of autumn wind. Then she affixed a flurry of paper leaves that looked as if they'd been scattered by the breeze.

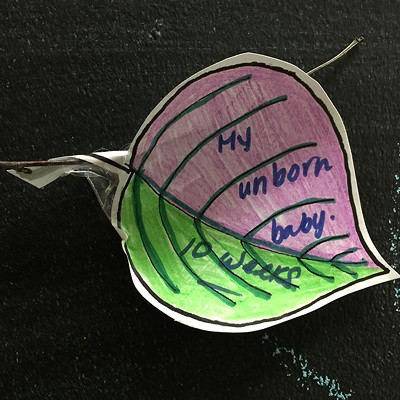

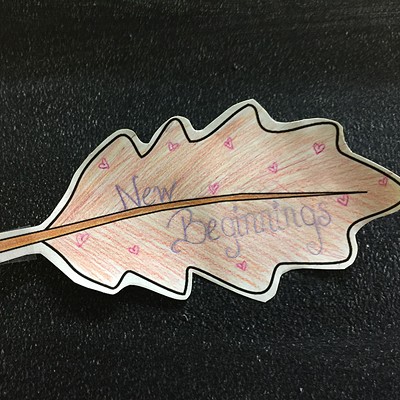

The leaves, decorated by guests, came in a few different shapes, but each was uniquely embellished. Some resembled fall foliage. Others were adorned with outlandish hues. Most were labeled with things for which guests were thankful.

"My unborn baby, 10 weeks," read a purple and green aspen leaf.

"New Beginnings," read a brown oak leaf studded with tiny pink hearts.

An expertly shaded red and gold maple leaf read simply, "Being ALIVE."

'It Works'

It's hard to say exactly how many people visit Turning Point — its staff and volunteers log roughly 3,000 visits a month, though some are repeats. The center's events calendar suggests there's almost always something going on.

Turning Point is open to the public for support and other activities from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m.; recovery coaching appointments and various meetings take place every evening. Guests can participate in arts and crafts workshops and writing groups, exercise in a small fitness area, or attend one of dozens of 12-step meetings the center hosts each month.

It also offers access to a wide variety of wellness opportunities, including meditation, Reiki, yoga, "peaceful warrior" karate classes, smoking-cessation support and acupuncture therapy, known as acudetox, to help manage withdrawal symptoms.

Retired South Burlington city manager Chuck Hafter volunteers at the center two mornings a week helping guests to find stable employment. "It gives me more than I give it," he said of his counseling work. "My empathy has completely gone through the roof."

Hafter points out that money isn't the only reason the people he sees want jobs — employment also boosts their self-confidence. It gives them a place to be and a sense of belonging.

"People want to work," he said. "People are proud when they have a résumé. People are proud when they pay taxes! Seriously."

Not surprisingly, some of Turning Point's guests have become its employees. After they've been in stable recovery for 60 days, they may start volunteering at the center, doing menial but essential tasks — checking people in, making coffee, taking out the trash. Those who've been in recovery a year or more may work as peer support counselors, which helps them establish an employment history.

click to enlarge

- Oliver Parini

- Sara Glasgow (right) making jewelry with a guest at the Turning Point Center

Glasgow took that route. After getting sober, she volunteered, then worked as a part-time peer support counselor and is now employed at the center full time.

Burlington's Turning Point is the largest of 12 peer-run recovery centers in Vermont; eight of them use the Turning Point name. Although they share a similar approach and receive funding from the state, each is an independent nonprofit.

The Bank Street center operates on about $317,000 annually — a little more than a third of which comes from the Department of Health.

The rest comes from fundraising. The organization's single biggest moneymaker is the Circle of Stars benefit dinner, which took place two weeks before Thanksgiving at the Comfort Suites in South Burlington.

Attorney General T.J. Donovan emceed the annual soirée, which he's done several times since the first one in 2010. Burlington Mayor Miro Weinberger, a past president of the Turning Point board of directors, was there, too, along with many current and former legislators.

"I can tell you this about the Turning Point Center," Donovan told the audience of Vermont glitterati. "It works. It works."

Matthew Cleare, a CPA and supervisor at Davis & Hodgdon Associates, served on the Turning Point's board of directors from 2008 to 2015. "Dollar for dollar," he said, "I think it's probably one of the most effective ways we keep people out of relapse and recidivism."

The mood at the dinner that night was upbeat. The center has struggled financially in the past — executive director Gary De Carolis confided later that, when he arrived at Turning Point five years ago, "there were hardly two nickels to rub together." Today it's in the middle of a $500,000 capital campaign to buy a building.

The center has nearly outgrown its current 3,300-square-foot space, which includes four cramped offices, a conference room and a large, L-shaped common area that has to accommodate meetings and yoga classes at the same time.

The new 5,500-square-foot space under consideration would house a real fitness center, seven staff offices, four meeting rooms, and an area for new moms and infants. Like the current location, it's downtown, close to the bus line and other social services.

So far, Turning Point has raised $380,000 for the new center, $230,000 of which came from just two grants. The Hoehl Family Foundation and the University of Vermont Medical Center's Community Health Investment Fund supplied $115,000 each. Board president Craig Weatherly said he hopes to make the move by summer 2018.

Thanksgiving Stories

"I used to be a party person," Israel Cave said of his problem with marijuana and alcohol. On Thanksgiving, the 76-year-old retiree sat at a table wearing a scarf and puffy vest, nursing a cup of coffee. "I guess you might call me the black sheep of my family," he said.

Cave has been sober for years, "through the grace of God," as he put it; his faded blue baseball cap read "Christian Love in Action." Cave said he usually lives in a tent on land in Williston — with permission from the owner — but is currently staying at a local motel. He's frequented Turning Point since it opened. "This is one of my favorite places in Burlington," he said as he sat back and took in the scene. "It's a great place for people just to stop in and connect."

Increasingly, those people include parents and their children. That morning, coordinator Kelly Breeyear led a recently launched new moms and moms-to-be support group. A few kids played with donated blocks, Matchbox cars and stuffed animals while their parents talked with Breeyear. The 37-year-old Burlington mom brought along her own children — son Jack, 9, and daughter Marlee, 6. They read books and played games on one of the center's four desktop computers.

Breeyear, who grew up in Winooski, was a high school basketball player when she first tried opioid painkillers; her doctor prescribed them after her knee surgery. She graduated from high school and trained to be a licensed practical nurse at Vermont Technical College but continued to struggle with chronic pain. When physical therapy and other approaches didn't work, she went back to opioids for relief and eventually became addicted. She lost her job after making a medical error with a patient. She and her kids were homeless for a time.

At her lowest point, Breeyear started shooting up heroin, which she said was her "never" drug — as in, she had always said she would never do it.

"I was really sad and in a really tough place," she remembered. She started thinking that her kids might be better off without her.

In January 2015, after a relapse, Breeyear managed to get and stay clean, with help from Lund, an organization that supports pregnant women and new moms. She and Marlee lived in Lund's residential treatment center, while Jack stayed with his dad.

Marlee's dad, Shawn Carter, overdosed last year on a mixture of heroin, fentanyl and cocaine. In a departure from conventional norms, his family explained the cause of death in his obituary, using it as a public warning about the dangers of heroin addiction.

Breeyear started volunteering with Turning Point last summer. When the center received a grant a few months later to fund a new-moms program, she got the job.

"I hadn't worked in a long time," Breeyear said. "I was really nervous."

But, so far, "it's been amazing," she gushed. "I could never have imagined what I've done already in a month and a half."

The week before Thanksgiving, Breeyear shared her story with an assembly of Burlington High School students, alongside Donovan and U.S. Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.). A week and a half after the holiday, she joined Sanders and U.S. Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.) at Lund for a press conference announcing a new federal grant to help families affected by substance use disorder.

Speaking out has given her confidence, she said, and it helps to combat the social stigma of addiction. "It's paid off tenfold," she said.

When she wasn't counseling families on Thanksgiving, Breeyear was making mini blueberry muffins using a small tabletop press; Marlee and Jack distributed them to center guests. Both kids helped carry a tray of the treats into the common room, with their mom following close behind. Marlee walked up to guests asking, "Do you want a muffin?" A few said no, but a young pregnant woman accepted one.

"She's growing a baby in her belly," Breeyear told her daughter.

The kids also approached a lanky young man sitting at a nearby table. He wore a T-shirt that revealed numerous tattoos on his arms; at his feet was a large backpack stuffed with clothes. The man had been sitting quietly with a few friends, occasionally rummaging through his pack.

When Marlee offered him a muffin, he turned and gave her a wide grin. "Thank you very much!" he said.

The little girl smiled back.

Turning Point?

Burlington's Turning Point wasn't always such a supportive, welcoming space. Weatherly recalled that when he started volunteering with the organization in 2011, it was "struggling" financially and operationally.

The silver-haired lawyer offered a diplomatic assessment of the center's climate back then: "We had a lot of people coming in who were here for reasons unrelated to recovery," he said.

Cave put it more bluntly: "It used to be a Wild West kind of place, where people used to do drug deals."

De Carolis recalled an encounter from that time. Shortly after he started working there, a guest came in and kept falling asleep on one of the center's couches. De Carolis woke him up three times and finally asked him to leave.

"On his way out," the director recalled, "he flings a metal chair at me." De Carolis ducked, and the chair crashed into the wall. "I yelled to a volunteer, 'Call 911!' And the guy says, 'Are you going to call the police on me?' He comes at me; the volunteer grabs him, knocks him to the ground, puts him in the elevator and sends him down.

"In those days," De Carolis concludes, "it was still a little bit of life-and-death here."

No one person is responsible for the center's evolution, but De Carolis has clearly been a big part of it. Nearly every Turning Point supporter, volunteer and guest interviewed for this article gave him credit for positive changes at the center.

One thing that sets him apart: De Carolis, 67, is the only Turning Point executive director in Vermont who's not in recovery.

He's also held elective office. He served three terms as a Burlington city councilor, from 1981 to 1987, while Sanders was mayor.

A New Jersey native, De Carolis first moved to the state in the 1970s, after graduating from Kean University with a bachelor's degree in social welfare. He earned a master's in counseling from the University of Vermont, where he also worked as a mental health counselor. De Carolis then spent most of his career as an administrator, first at the state's Department of Developmental Disabilities and Mental Health Services — where he rose to the level of deputy commissioner — then in Washington, D.C., where he oversaw child and mental health programs for the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services.

He returned to Vermont in 2002 and worked as a freelance leadership consultant. In 2012, De Carolis started a side business giving Burlington history tours.

In December of that year, a friend serving on the Turning Point board of directors asked him to fill in as the interim director while the center searched for a new leader.

De Carolis took the gig in mid-December and quickly realized he wanted to stay on; he'll celebrate five years there on December 17. As he told the audience at the Circle of Stars dinner, "My goal in life is to make life better for people. I found the epicenter of what that's about in the Turning Point Center."

At work, De Carolis is frequently interrupted by phone calls and requests from staff, volunteers and guests, yet he always seems to project an aura of calm and competence.

"He's a steady force," said Glasgow. "He's this solid foundation, always moving forward."

The center has made some changes since De Carolis took over. For starters, Weatherly noted, the staff and volunteers made it an "uncomfortable" place for guests who weren't invested in recovery.

Their methods included randomly timed, mandatory group activities known as "flash mobs." A staff person or volunteer would make everyone in the center stop what they were doing and gather in a circle. They would all introduce themselves and answer a question such as, "When times are tough, what helps you stay in recovery?"

It was a good community building exercise that helped everyone get to know each other a little better, according to Weatherly. And it helped identify guests who weren't interested in getting better. Said De Carolis: "They'd just split faster than you can say 'flash mob.'"

Another change: The center got rid of its couches and replaced them with tables and chairs. And the restrooms are now locked; volunteers with keys open them for guests upon request and inspect the bathrooms afterward.

The center has also improved volunteer training and changed its staffing practices so that there's always one person whose sole focus is keeping an eye on who's using the common area. That way, even if the staffers are busy, someone is monitoring who's coming in and hanging out.

The common area monitor assesses guests as they enter, paying attention to their eyes, speech and mannerisms. Everyone has to sign in upon entering, and often a volunteer will ask, "Clean and sober and in recovery?"

If there's reason to think the answer is no, the volunteer or a staff person will pull the guest aside and offer assistance with getting into detox. "If they're up for that, we'll do it," said De Carolis. If not, the guest will be asked to leave.

The state requires the center to track guest visits and the number of one-on-one interactions. Two years ago, the center also created an anonymous online survey, which guests take using an iPad set up in the common area.

It includes questions about length of recovery, substances used and other stressors unrelated to addiction. The survey revealed heroin's prevalence as a drug of choice. And it has shown that 60 percent of Turning Point guests are in their first year of recovery — the time when it's critical for them to break old habits and make new, healthier connections.

The data have helped De Carolis write grants and add programming. When the survey determined that oral health was one of the biggest stressors for people coming to Turning Point, De Carolis secured funding from Delta Dental for a dentist to make quarterly visits to the center. "Who's flossing and brushing their teeth when they're in the midst of addiction?" he asked rhetorically.

The idea for the survey, De Carolis said, came from an intern from the Community College of Vermont. Turning Point now works with students from CCV, Champlain College and UVM.

Judith Christensen, a senior lecturer for UVM's psychology department who oversees internship placement, has known De Carolis since his days as a counselor at UVM. She started sending him interns three years ago.

Turning Point is "probably one of the best programs for psychology students to see what the real world is all about," she said. "They really get to understand the population in a way they would never get to from a textbook."

The Art of Transformation

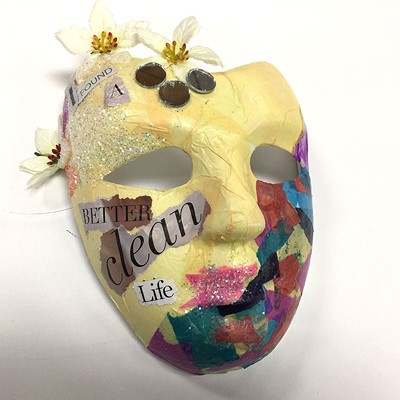

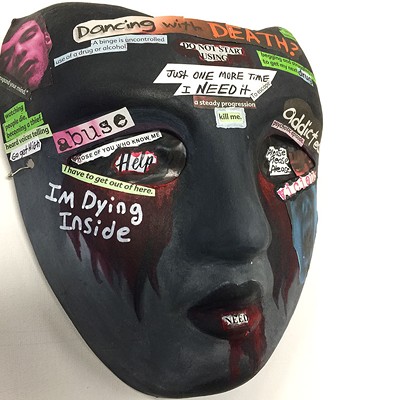

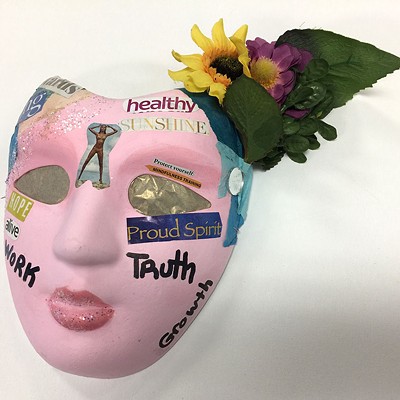

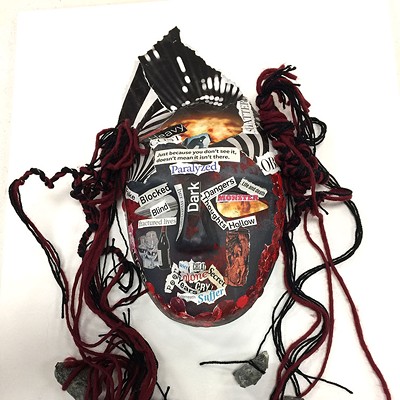

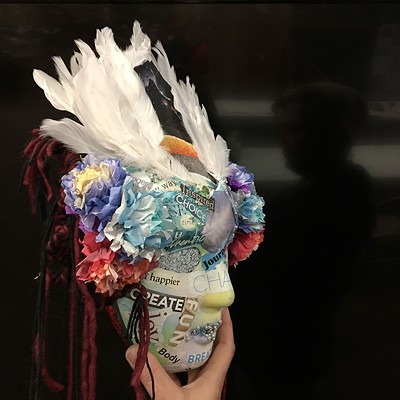

Glasgow, Turning Point's resident artist, has found a niche helping guests better understand themselves. During her workshop called The Masks We Wear, she got them to make plastic and papier-mâché masks illustrating addiction, recovery or both.

One woman colored her addiction mask black, with dark-red stains oozing from its eyes and mouth. Glued to it are eerie pictures of eyes, and people screaming, with words and phrases cut out from magazines: "Tweak," "I have to get out of here," "Help," "Kill me," "Just one more time. I NEED it."

One man made a pink and purple recovery mask, topped with a golden butterfly and beads painted gold to resemble a crown. "One side represents his girlfriend," Glasgow explained. "The other side represents his child to be."

Adopted at age 6 after living in various foster homes, Glasgow was raised by a Strafford couple that ran a painting restoration business. Her dad would fix the physical defects; her mom would mix colors to get the right shade.

"I saw paintings come in there that looked like a tiger had ripped them to shreds," Glasgow recalled. "By the end, you wouldn't be able to tell. That was like magic."

Seeing that process kindled an interest in transformation. At first, Glasgow thought she might like to be an actor, but she was drawn instead to set design, body painting and theatrical makeup.

She started drinking at 13 or 14 because it made her feel grown up and sophisticated — it was "getting in touch with the muse," she said.

Glasgow's drinking intensified when her son, now 14, was diagnosed with leukemia. Her marriage fell apart. When she and her son went to live with a friend, Glasgow tried to hide her drinking, but her friend caught on and told her she needed to get help.

"She could see I was self-destructing," said Glasgow, who had a suicide plan.

Instead, Glasgow went into detox and treatment; her son, then in remission, stayed with her friend for nine months.

After Glasgow moved back in with her son, she sought psychiatric help from the UVM Medical Center. She had her addiction under control but was grappling with the effects of the trauma she experienced as a young child. She ended up in the hospital's outpatient Seneca Center program.

Turning Point is where Glasgow did her "homework." As a volunteer, and then as a peer support worker, she started sharing arts and crafts ideas with De Carolis and daytime operations manager Ken Johnson. That work led to her current position.

"When I started making art again was when I knew I was getting better," she said. Glasgow's own terrifying addiction mask is topped with strands of black and red yarn — hair — with palm-size gray rocks tied to the ends to represent the way her drinking dragged her down.

Thanks to generous donations — and some money from her own pocket — Glasgow now has a closet full of art supplies: paints, clay, beads, colored pencils. "It's like a candy store," she said, proudly showing it off.

She puts the supplies out at certain times during the week and also runs workshops.

At first, some guests are reluctant to engage. "They'll say, 'I'll just watch. I'm not artistic at all,'" Glasgow said. "Before you know it, they're making a bracelet for their son, their daughter, their mother, discovering something to get excited about. So often we lose that in addiction."

She said the mask project gave participants "a feeling of, I'm doing something proactive with it. I'm getting it out of my head."

Glasgow didn't get choked up telling her own recovery story, but she wiped away tears when describing an encounter she'd had the day before with a woman who'd just been released from prison. "She asked me, 'Does it really get any better?'" Glasgow recalled.

"To my very core, I was so glad that I could look her in the eye and say, 'Absolutely. I didn't think it would, and it has.'

"That," continued Glasgow, "is why I'm here."

The original print version of this article was headlined "The Clean Room"

Related Locations

-

Turning Point Center

- 179 S. Winooski Ave., Suite 301, Burlington Burlington VT 05401

- 44.47497;-73.21097

-

802-861-3150

802-861-3150

- www.turningpointcentervt.org

-

Be the first to review this location!

Related Stories

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

More By This Author

About The Author

Cathy Resmer

Bio:

Deputy publisher Cathy Resmer is an organizer of the Vermont Tech Jam. She also oversees Seven Days' parenting publication, Kids VT, and created the Good Citizen Challenge, a youth civics initiative. Resmer began her career at Seven Days as a freelance writer in 2001. Hired as a staff writer in 2005, she became the publication's first online editor in 2007.

Deputy publisher Cathy Resmer is an organizer of the Vermont Tech Jam. She also oversees Seven Days' parenting publication, Kids VT, and created the Good Citizen Challenge, a youth civics initiative. Resmer began her career at Seven Days as a freelance writer in 2001. Hired as a staff writer in 2005, she became the publication's first online editor in 2007.

Speaking of...

-

What's That New Mural on King Street?

Aug 1, 2019 -

Turning Point Center Celebrates Its New Digs in Burlington

Jan 15, 2019 -

The Strength Within: Kelly Breeyear Helps Fellow Moms Fight Addiction

Dec 15, 2018 -

The Strength Within: Kelly Breeyear Helps Fellow Moms Fight Addiction

Dec 3, 2018 -

Opiates, Love and Loss: A Vermont Woman's Obituary Strikes a Global Chord

Oct 24, 2018 - More »

Comments (3)

Showing 1-3 of 3

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.

- 1. Burlington Budget Deficit Balloons to $13.1 Million News

- 2. Scott Official Pushes Back on Former State Board of Ed Chair's Testimony Education

- 3. Legislature Advances Measures to Improve Vermont’s Response to Animal Cruelty Politics

- 4. Senate Committee Votes 3-2 to Recommend Saunders as Education Secretary Education

- 5. Vermont Rep. Emilie Kornheiser Sees Raising Revenue as Part of Her Mission Politics

- 6. Norwich University Names New President Education

- 7. Barre to Sell Two Parking Lots for $1 to Housing Developer Housing Crisis

- 1. Totally Transfixed: A Rare Eclipse on a Bluebird Day Dazzled Crowds in Northern Vermont 2024 Solar Eclipse

- 2. Zoie Saunders, Gov. Scott’s Pick for Education Secretary, Faces Questions About Her Qualifications Education

- 3. Don't Trash Those Solar Eclipse Glasses! Groups Collect Them to Be Reused 2024 Solar Eclipse

- 4. State Will Build Secure Juvenile Treatment Center in Vergennes News

- 5. Vermont Awarded $62 Million in Federal Solar Incentives News

- 6. Queen of the City: Mulvaney-Stanak Sworn In as Burlington Mayor News

- 7. New Jersey Earthquake Is Felt in Vermont News

![The Healing Power of Yoga [SIV515]](https://media1.sevendaysvt.com/sevendaysvt/imager/u/square/11207180/episode515.jpg)