Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

-

Education

Scott Official Pushes Back on Former State…

-

News

Burlington Budget Deficit Balloons to $13.1 Million

-

Education

Senate Committee Votes 3-2 to Recommend Saunders…

- Court Rejects Roxbury's Request to Block School Budget Vote Education 0

- Norwich University Names New President Education 0

- Media Note: Mitch Wertlieb Named Host of 'Vermont This Week' Health Care 0

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

Turning the Mic Around on Jane Lindholm, VPR's Most Recognizable Voice

Published January 13, 2021 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated February 9, 2021 at 4:50 p.m.

Updated January 24, 2021.

You would never have known by listening to her crisp, assured voice on Vermont Public Radio that Jane Lindholm was hosting "Vermont Edition" from her kitchen table in Monkton with a dog blanket over her head for soundproofing. Since the start of the coronavirus pandemic, she's done some of the live intros and wrap-ups for the governor's twice-weekly press conferences from home, over a landline, amid all manner of distractions. On a Friday in November, those included the family's arthritic dog, Oliver; Lindholm's 4-year-old daughter, Carys, who never stops talking; and a reporter documenting it all from a safe distance on the screened-in porch.

Preschool was closed that day, and Lindholm's husband was working a 12-hour shift at GlobalFoundries. Operating remotely, VPR's most recognizable radio journalist had to figure out how to quiet her daughter, and fast. Their living-room negotiations — iPad or colored markers? — lasted until seconds before 11 a.m., when Lindholm returned to her laptop and tented herself with it.

After a few minutes of silence while VPR was broadcasting national and local news, the fleece pyramid spoke: "And I'm Jane Lindholm, joining you now with special coverage from VPR of Gov. Phil Scott's Friday press briefing."

With her Montpelier-based cohost, Bob Kinzel, Lindholm has been doing this for months on Tuesdays and Fridays, in lieu of the regular noontime talk show that she has hosted four days a week since 2007. While they wait for the real-time proceedings to begin, she and Kinzel talk on air about what state leaders might discuss that day.

After the press conference, they reconvene for a debriefing of what just transpired — often breaking news. Their professional exchange, mostly improvised, is audio therapy, as soothing and reassuring as a pair of voices can be in anxious times.

Sometime last summer, Lindholm started weighing in during the press conferences, too, with rapid-fire real-time reports on Twitter. Turns out she's a very fast typist and is able to explain, in writing, what just happened while also actively listening to what's currently being said.

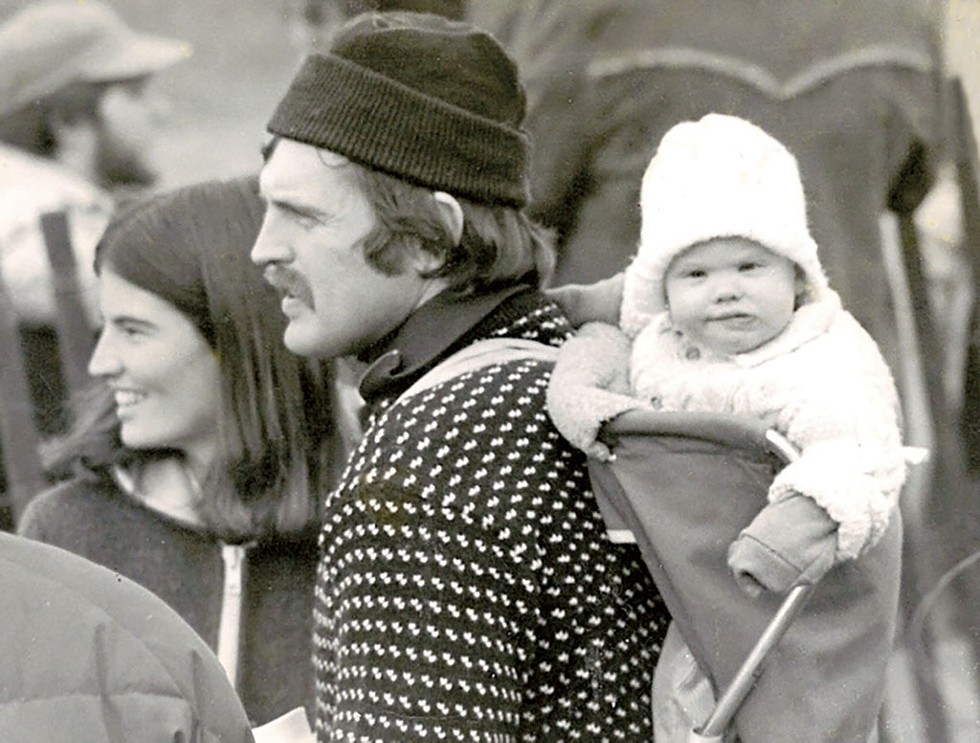

click to enlarge

- Luke Awtry

- Clockwise from top left: Adrian Hicks, Jane Lindholm, Carys, Oliver and Dylan

In her posts, Lindholm packs policy changes, quotes, charts, queries from other journalists — and occasional personal anecdotes about making lunch, dog disasters and looking after her kids. An hour in on the day I visited, she inserted, "My daughter is asking for a pickle and mustard sandwich, with a pickle on the side. So I'm going to multi-task for a few minutes." At 1:24, "My daughter has taken this opportunity to start drawing on her face. Good times!" got 29 likes.

The resulting Twitter thread is a curated transcript of the official proceedings, with humanizing glimpses into the life of the narrator.

"I just started doing it and people seemed to like it, so I kept doing it," said Lindholm, explaining that she had to listen and take notes on the press conference, anyway, to prepare for the wrap-up with Kinzel. She figured, "I might as well tweet it." Then "VPR started noticing that other people were noticing. They now see it as a thing."

The "thing" for which Vermonters know Lindholm best — her role as longtime host of VPR's "Vermont Edition" — is coming to an end next month. In the past 13 years she has turned the noontime talk show into the station's signature news program by "listening, really listening to the stories of the lives of Vermonters," said John van Hoesen, senior vice president and chief content officer at VPR.

Approximately 64,000 people tune in to the show each week, according to the latest Nielsen Audio ratings, and thousands more download the podcast. "Vermonters have been able to see themselves in Jane," van Hoesen continued. "She is the authentic journalist in pursuit of truths that matter to us. And she uses her own curiosity, persistence and compassion to get at them."

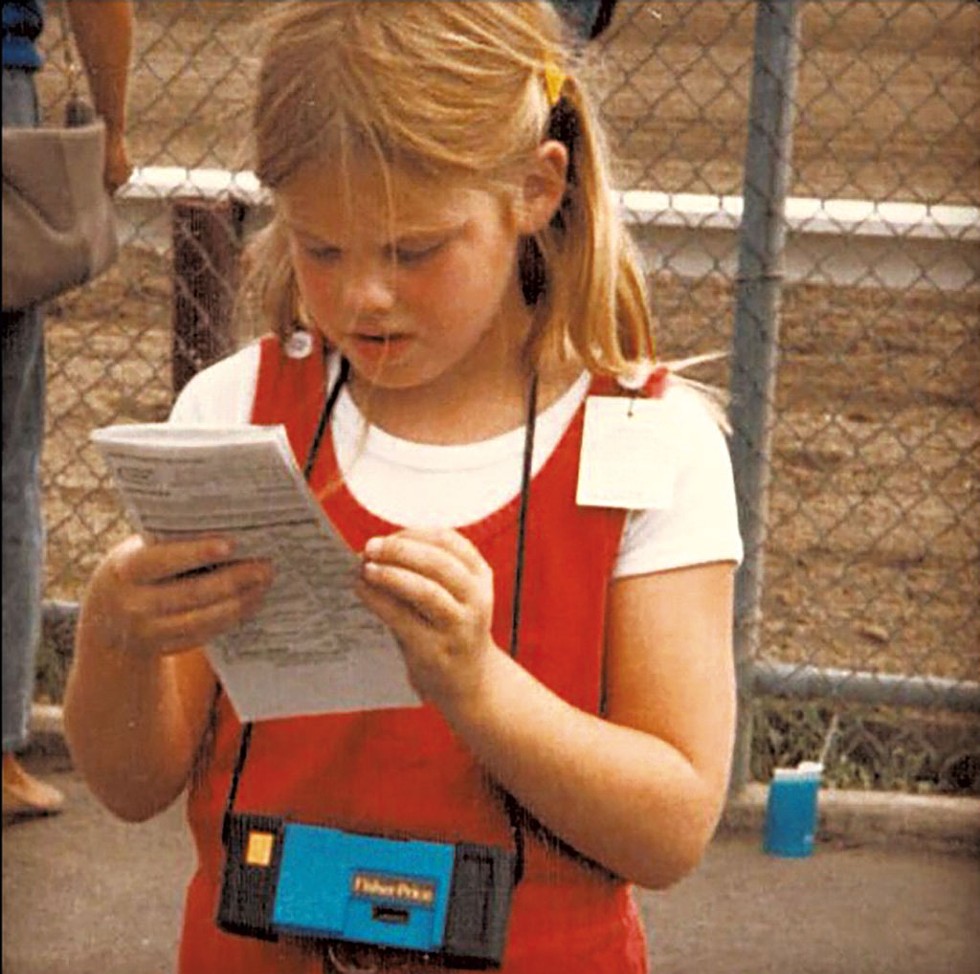

Roughly five years ago, Lindholm created "But Why? A Podcast for Curious Kids" without reducing her workload as host of "Vermont Edition." She juggled the two gigs until the pandemic closed schools and childcare centers last March. Suddenly, her two kids — Carys and her 7-year-old brother, Dylan — were at home all day. Lindholm, a self-described perfectionist, felt she had to make a choice. Last fall the station announced she'd leave "Vermont Edition" in order to focus on expanding and improving "But Why?" with longtime producer Melody Bodette. Since March, the biweekly podcast has been downloaded more than 6 million times.

It says a lot about 41-year-old Lindholm that she opted for an uncharted challenge over the reliable local celebrity of hosting Vermont's highest-profile talk show. After an early, unwanted disruption in her life — her parents' divorce — Lindholm has sought out risk and change, and their potential attendant discomforts, in order to keep learning and growing. Nobody would be surprised if she left Vermont; she's got the requisite talent and ambition to be successful in a bigger market. But for now Lindholm is staying put, balancing work and family, trying to be as good a mom as she is an ambitious, whip-smart radio journalist. And occasionally combining the two.

Interviewer in Training

Everything about Lindholm suggests she'd be a great interview. Her warmth comes through on the air, suggesting openness and self-awareness. Starting with our first chat, walking through the woods at Bristol's Watershed Center, she did not hold back: "I like to be on the other side of the microphone, but as you can see, I have no problem talking," she said with a laugh.

To clarify, Lindholm doesn't just "talk." She utters grammatical, well-constructed sentences that coalesce into thoughtful paragraphs — broadcast-quality meditations. She doesn't swear and rarely says "like," "you know" or "um."

Despite frequent interruptions — from myself and Carys — Lindholm kept multiple narrative threads intact as we hopped from log to log across a beaver pond or stopped to chat with fellow hikers Marjorie Susman and Marian Pollack. In four hours of interviews spread over a month, Lindholm never misspoke or contradicted herself.

Some of this can be chalked up to the skills of an experienced radio journalist. Lindholm relayed her own biography with the same thoughtful analysis with which she approaches her guests. She was honest but also freakishly well prepared — down to recalling the topics of her college essays.

Ultimately, "profiling" her proved more difficult than expected because she was controlling the story. I came to realize this is someone who has thought long and hard about the best way to tell her own tale.

Early on, for example, Lindholm volunteered what seemed to be a preemptive acknowledgment that, in addition to her own hard work, "luck and privilege ... have come together in so many ways for me ... to give me the life that I have." The older she gets, Lindholm said, the more weight she gives to "luck and privilege."

She did have some advantages in life: specifically, the kind of education generally reserved for the affluent and the children of academics. At the time Jane was born, in 1979, both of her parents worked at Middlebury College, where her father became the dean of students. When they divorced eight years later, Karl stayed in Vermont, remarried and had two more children. Lindholm's mom, Jody, reclaimed her maiden name and moved Jane and her younger brother to Massachusetts — first to Wellesley and then to the private Brooks School in North Andover, where she was assistant headmaster.

The long, painful breakup of her parents took a toll on Lindholm. "I was 4 when things got bad," she recalled. It also marked her first exposure to the complexities of human interaction. Seeking clues that would explain the behavior of the adults in her life — "all my parents" is how she refers to them — she first learned to ask the kind of probing questions that would make her a skilled interviewer.

Her mom remarried, too, and Lindholm's stepfather, Dan Warthman, was a role model and cheerleader in the years when Lindholm attended Brooks tuition-free. He was the primary caregiver for his stepchildren, wrote short stories on the side and later became a private investigator. "He and I would work on my essays together for English class," Lindholm recalled, noting they'd often argue into the night about writing and sentence structure.

Lindholm had opportunities at Brooks that her family wouldn't otherwise have been able to afford. She made the most of them, including the chance to spend three months attending high school in Nairobi, Kenya.

"I wanted to know: What is it like to see America from not America? And what is it like to experience other parts of the world? And what is it like to be a little uncomfortable in the place where you live?"

Studying in Kenya was an eye-opening experience, complete with urban squalor, school uniforms, dormitory living and a knuckle-rapping typing teacher. "Now that I'm a parent, I think that the people who were really brave were my parents. How do you let a 17-year-old get on a plane to Nairobi? ... They allowed me to take risks without burdening me with their fears. That's helped shape who I am, I think."

Lindholm wrote about the African experience in her college applications to Harvard and Yale. She got in to the former but in retrospect believes she would have been happier at Middlebury or Bates. She avoided the alma maters of her biological parents because, she said, "I really wanted to prove to myself that I could get into a school on my own merits."

She also wanted to row crew.

Lindholm had the discipline to get up every day at 5 a.m. to set the pace in the first freshman boat. But a persistent back injury from high school forced her to quit the sport in the middle of sophomore year. After a "lazy" stretch, she switched to running. Lindholm tries to squeeze in a jog every morning between dropping off her kids at their schools and a 10 a.m. news meeting. If it doesn't happen, she runs at night.

"I feel so much better when I exercise," she said, noting she logged 140 miles in December.

Participating in a competitive college sport gave Lindholm an identity at Harvard. Losing it caused her to wonder: Do I even belong here? Plus, she found her grades — As and Bs — didn't reliably reflect the magnitude of her effort. "None of the professors or teaching assistants could tell the difference or cared how engaged I was," she said.

She found a new outlet at Let's Go, the travel book series written, photographed, edited and designed by Harvard students. In the summer of 2000, Lindholm helped edit two books. The next year, after a semester studying in Chile, she went to Spain to report and write another one.

Lindholm was determined not to major in English or literature because all four parents had. Guided by her interests in language and travel, she chose anthropology and got a BA in the "study of why we behave the way we do," which, as it turned out, perfectly prepared her for a career in journalism.

Sounds Like...

Charting Lindholm's course from Cambridge to Colchester requires more than a map of New England. While still at Harvard, she had a friend whose father was on the board of the NPR Foundation. He arranged for Lindholm to talk with Kevin Close, a Harvard alumnus who was then president and CEO of the network. Close suggested that Lindholm send a résumé and cover letter to NPR. She did, but there was no immediate response, so she pursued other opportunities.

She was in Spain, working on that travel book, when one of her best friends died while doing similar work in Peru. Shaken, Lindholm returned to the United States and was "totally adrift" when she got a call from a producer offering her a spot at a Washington, D.C.-based NPR show called "Radio Expeditions." The woman had found her résumé and cover letter in a pile. "I thought it was a joke," Lindholm said. "I really thought it was one of my friends in an ill-advised attempt to cheer me up because they knew I liked NPR."

The unpaid internship, which Lindholm negotiated into a low-paying job, "was mostly to transcribe hours and hours and hours and hours of sound," she explained — in one case, collected from a trip to an elephant watering hole. She'd note audio such as "'long moan,' 'three grunts in a row,' 'loud grunt.' I mean, it was bizarre," she said. But the experience taught her "how sound can tell a story and how involved it can be."

Just five days after she started working, Lindholm was on the subway crossing the Potomac River from Virginia when she saw smoke rising from the Pentagon. Her train had just passed under the building, and Lindholm was facing backward, so she got a clear view of the aftermath of the terrorist attack on Washington on September 11, 2001.

She spent a few days calling the families of victims to find out whether any of them would talk to NPR. With no bereavement training, Lindholm joined "the worst phone bank imaginable" and found she had the combination of empathy and thick skin required to handle those difficult conversations.

The intensity of the experience had an impact; so did the deaths of three more classmates while abroad. Lindholm remembered concluding: "I'm going to be next. Why am I not in the place where I can be with my family, because I could die at any moment? I really struggled."

One night in early November 2002, Lindholm decided to walk home in lieu of taking the subway. She got mugged within sight of her apartment. She screamed at the guy, and then saw he had a gun. "I thought, Oh, my God, now he's gonna shoot me. And he didn't."

"It was totally scary, but it shook me loose. It was this moment where a bad thing happened and I didn't die. And so it made me realize, oh, OK, you have to just keep living your life and you have to just, you know, keep moving forward. And rather than live your life like every day could be your last, I felt like I had to live my life like I was gonna have a long life. And so I had to make plans."

In the months after 9/11, Lindholm had picked up extra hours working at "Weekend Edition," which was produced in the same building as "Radio Expeditions." From host Scott Simon and his colleagues, she "learned about the importance of really good audio editing, for voices." She moved on to a staff job at the call-in show "Talk of the Nation" but wasn't moving up in the ranks.

"I was a production assistant the whole time I was at NPR," Lindholm said of that year and a half. So she felt no guilt about jumping on a plane to Australia, two months after the mugging, to do another book for Let's Go. That gig led to a sojourn in Southeast Asia. Lindholm met her future husband, Adrian Hicks, on a beach in Thailand. Lindholm, whose previous relationship had been with a woman, said the two teamed up to explore Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam, and then "started dating."

The romance survived the tests of time and distance. Hicks returned to his native Wales, and Lindholm got a job as an assistant producer at American Public Media's "Marketplace" in Los Angeles. She quickly moved into the job of running the show, gaining experience in everything from audio engineering to reporting stories.

After three years of it, though, she'd had enough. "All my family was back East. Adrian was in the UK. I had two weeks of vacation a year," Lindholm recalled. So in December 2006, when she came home for Christmas, she set up an informational interview with then-VPR news director van Hoesen. "That's when he told me that they were starting up a new show and they were going to be recruiting for producers and a host," Lindholm recalled.

From back in LA, she applied for both jobs and later clarified to VPR that she would only leave "Marketplace" for one of them: to be the live, on-air voice of "Vermont Edition."

'High-Wire Act'

Lindholm acknowledges that VPR took a huge risk by hiring her. Although she had national credentials and knew Vermont, "I'd never done a second of live radio in front of a microphone where I was the one speaking as it was being broadcast," she explained. Vice president of news Sarah Ashworth, who came to VPR a month after Lindholm started, recalled a Post-it note over Lindholm's desk with the word "so" crossed out — the host's reminder to herself to break the annoying habit of starting sentences with it.

The show itself was a gamble for the station, too. An astounding amount of work goes into creating a single hour of live radio. In the early years, "Vermont Edition" employed Lindholm, an editor and three full-time producers, one of whom was Ashworth. The producers were charged with finding and researching story ideas that could be suitable for the show.

Although she wasn't in charge of finding stories or booking guests, as host Lindholm was supposed to "come to every conversation feeling fresh, curious and excited," she said. She learned on the job, embracing the daily preparation involved for each episode: formulating the questions, writing the intro, reading the books, synthesizing the notes provided by producers.

Ashworth, who later worked for NPR's national call-in "Diane Rehm Show," said Lindholm's "commitment in terms of each individual show and the attention she gives to it ... is not typical of hosts at other stations."

Lindholm likened it to "cramming for a test" but with some key differences. "You need to know enough to ... ask the right questions ... But I don't need to know all the answers. Because I'm not the expert; the guests are the experts. I don't like hosts that show off their knowledge. That's what the guest is for."

That approach has yielded hours of remarkable radio, as Lindholm queried Vermonters about everything from politics and the pandemic to bugs and birds. "She was as eager to go one-on-one in an interview with the governor" as "to get in the field to track bears," recalled the show's founding executive producer, Patti Daniels, who now works for Public Radio International's "The World."

Lindholm's approach has been versatile, too. Depending on the subject, sometimes "Vermont Edition" sounds more like an intimate conversation than a news show. She combines a reporter's precision probing with the nonjudgmental coaxing of a therapist.

"It was just a breath of fresh air when she took over," said Susman, the woodland walker who listens to the show every day on her farm in New Haven. "Don't you think of her as our own Terri Gross? She's so eloquent, so well informed and so human. She is a hoot on Instagram." Lindholm posts about her personal life — Adrian and the kids — on the social media platform. "She is so honest about her flaws at parenting," Susman added. "We're big fans."

Asked what it takes to be a good host, Daniels first described the qualities of a good journalist: "deep knowledge and preparation and reading" and "genuine curiosity to seek diverging points of view and information that supports those points of view."

But after all the research, "Vermont Edition" is a show. Although she's not acting, "it is a performance," Lindholm said. "You have to turn it on the minute you go on air, and then just focus. You don't check your texts or your emails. Your whole person is focused on this hour of radio. For me, anyway."

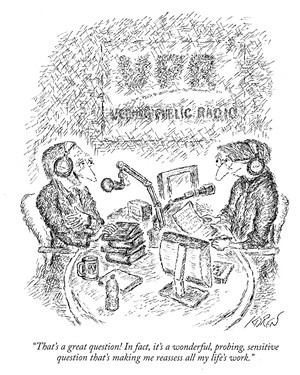

What's it like to be under that microscope? "She put me so at ease, it was a piece of cake," said Brookfield cartoonist Ed Koren, who suffers from pre-interview jitters. His positive experience with Lindholm inspired a cartoon that appeared in the March 23, 2020, issue of the New Yorker. It shows a radio journalist — "almost a portrait of Jane, but not quite," as Koren put it — interviewing "a creative sort" in a broadcast studio. With a stack of books before him, the man responds to his interrogator: "That's a great question! In fact it's a wonderful, probing, sensitive question that's making me reassess all my life's work."

Grilling elected officials has been trickier. "I often feel like I don't know enough to really dig into what the politicians are saying ... to be able to poke holes," Lindholm said. "That sort of live fact-checking element has become something that people want."

To extract the best material from a subject requires "an instantaneous ability to prioritize," Daniels said of the "high-wire act" of live radio. "You are just constantly triaging and making decisions, second by second." Being able to take the conversation to unexpected places "takes a real willingness to be authentic and comfortable with risk, while also managing the sheer volume of information."

In addition to countless episodes of "Vermont Edition," Lindholm and Daniels managed the station's live coverage of Tropical Storm Irene, which hit Vermont on August 28, 2011. In a departure from its usual format, the show became an information clearinghouse when floodwaters cut off transportation and communications to some Vermont towns. People called in with questions, anecdotes and pleas for help for two to three hours a day, all week. Lindholm facilitated the on-air improvisation.

Van Hoesen recalled, "At one point, I remember Jane making an appeal on behalf of one family who wanted to know if anyone had seen one of their family members. It was just one moment that characterized the anxiety that so many people were experiencing. It was one family's circumstance, but in a flash it was all of our circumstances. You can see something similar in her live-tweeting of the governor's press conferences on the COVID pandemic."

Learning how to respond to such unpredictable circumstances prepared Lindholm for live election coverage, which she also cohosts with Kinzel. "Bob and I have a system," Lindholm said. "I'm air-traffic control. He's analysis. It works for us."

Daniels and Lindholm, in contrast, didn't always get along. Although they remain friends and mutual admirers, "We both wanted to be in control, so that was really challenging for both of us," Lindholm acknowledged. "We did some professional marriage counseling for a while, and we did one of those personality tests." Not surprisingly, they turned out to be very similar: both perfectionists, aka control freaks.

"Jane has rightfully earned the trust and the respect of listeners," said Daniels, who left VPR in 2017. And Lindholm has effectively become the face of the station, emceeing public events, speaking at graduations, visiting schools. Ten weeks after Carys was born, Lindholm hosted an annual Vermont Women's Fund event and introduced former Vermont governor Madeleine Kunin. She wound up nursing her daughter in front of a huge audience.

"That was fun," she said, as if surprised by her own audacity. It seems that Lindholm, who for almost 14 years has drawn out others, is increasingly comfortable revealing herself.

'That's Jane'

Asked how she would describe her colleague, Ashworth said Lindholm is just as she appears on the air. "You know, she's really smart. She's really curious. She's really sharp. And, like, on it. She sees things clearly from the start."

On the day of our interview for this story, Ashworth canceled at the last minute. She'd just found out her dad was en route to the emergency room in Minneapolis, close to where she grew up. It was nothing serious, she told me the next day — possibly dehydration. But she'd texted Lindholm, too, before she knew her father was OK.

"The phone rang within 30 seconds," Ashworth told me. "I mean, that's Jane. She makes time for friendships. She's a good advocate, too."

Ashworth and Lindholm bonded in the early days of "Vermont Edition." Together they pondered questions such as: "Do we want kids? Can we ever afford to own a house? We were together, trying to figure that out," Ashworth recalled.

When Ashworth left VPR in 2010, the two women stayed friends, despite long stretches without seeing each other. For example, Lindholm was not going to let Ashworth give birth to her daughter, Anna, without a proper baby shower. Lindholm and Daniels drove to New Hampshire, where Ashworth was living at the time, and "just descended on the house. It was wonderful," Ashworth recalled. "She does that kind of thing for you. When she gives you a gift, it's like a homemade tincture" — something she grew or made herself.

Three years ago, Ashworth returned to VPR, this time as news director. Now in their forties, she and Lindholm have houses and children. Dylan and Anna are both in first grade.

"She and I talk a lot about having young kids at home ... the day-to-day, and just how hard it is to try to figure out what's best for your kid," Ashworth said. Last week Lindholm learned that a school friend of her son had tested positive for the coronavirus, so Dylan would have to quarantine at home for two weeks. She or Adrian will have to be there with him.

"I know she has struggled a lot in the last year," Ashworth continued. "I also know she's thought about and looked at other positions on a more national level or a larger market. But something has kept her here. And that's the mix of Jane."

The experience of developing "But Why?" has satisfied some of her friend's "internal ambition," Ashworth said, noting that each episode of the kid-focused podcast now reaches hundreds of thousands of people around the world. Lindholm and VPR share rights to the podcast, which has already generated interest from Hollywood film directors for a possible video series. In December, they inked a two-book deal with Random House. The first book is about farm animals; Lindholm wrote the second one — a 13-chapter book about ocean life for young readers — over the Thanksgiving break.

"But Why?" was entirely her concept, although the idea came from a Vermont mom who shared a parenting conundrum on social media: "How should I answer my son," she posted during breaking news coverage in 2012 of the Secret Service scandal in Cartagena, Colombia, when he asks, "What are prostitutes?"

Lindholm said, "I thought, There needs to be something that you can put on for your children that sounds like NPR but is geared toward them and won't make parents tear their hair out." Researching the market, she was surprised to find there weren't too many offerings in the kids-podcast genre.

Lindholm also discovered that people — including high-profile guests — are more likely to say yes to a kids' show. Before Thanksgiving, children could tune in to an episode titled, "Why Are We Still Talking About the Election?" with NPR White House correspondent Ayesha Rascoe, who simplified complicated concepts such as voter fraud and the Electoral College. A month later, the headline question was: "Why Do Things Seem Scary in the Dark?" featuring author Daniel Handler, aka Lemony Snicket.

"I think there's a lot of growth that we haven't explored for 'But Why?' and what it could be," Lindholm said, noting that, without her, VPR would discontinue the project. "It's not in our mission," she acknowledged. "It was this weird show that sort of has grown into something big. 'But Why?' could be a brand."

"I'm energized by this new opportunity," Lindholm continued. "I feel a real pull to speak to children and give them confidence that their ideas are valid, that their curiosity should be cultivated, that they should feel safe and secure."

Adult Vermonters will still hear Lindholm's voice, though not every day. Her new arrangement with VPR, aka "the transition," includes producing quarterly special projects for broadcast. Lindholm seems equally excited about the chance "to do important work ... things that make a splash or that feel like they're adding to the Vermont conversation in a big way."

I asked Lindholm what 17-year-old Jane would think of the 41-year-old version. She imagined the teen would be shocked to find herself living in rural Addison County, where she was born, instead of "living abroad, probably traveling — maybe in the foreign service."

Another expectation: "Definitely cooler looking." Two years ago, Lindholm cut her hair super short and dyed it purple. Now she's back to a brown bob and given to practical outdoor wear.

Something else was happening when Lindholm was 17, though. She had a 1-year-old half brother and a half sister on the way. "There was always a sense for me that I would have kids and be focused on family life," she said. "It doesn't look quite like what I thought.

"I struggle with how to keep myself professionally and creatively satisfied, while also realizing that it's not just about me," Lindholm continued. Hicks loves Vermont and doesn't want to leave; he's an avid hunter. Lindholm said she appreciates what her kids are gaining from growing up here — the family keeps bees, grows a garden and spends a lot of time in nature — but she also wants them to see the world. "How do we do all of that?" she wondered.

Good question.

The original print version of this article was headlined "Radio Head | Turning the mic around on Jane Lindholm, VPR's most recognizable voice"

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

Tags: Media, Jane Lindholm, Vermont Public Radio, VPR, But Why?, Vermont Edition

About The Author

Paula Routly

Bio:

Paula Routly came to Vermont to attend Middlebury College. After graduation, she stayed and worked as a dance critic, arts writer, news reporter and editor before she started Seven Days newspaper with Pamela Polston in 1995. Routly covered arts news, then food, and, starting in 2008, focused her editorial energies on building the news side of the operation, for which she is a regular weekly editor. She conceptualized and managed the “Give and Take” special report on Vermont’s nonprofit sector, the “Our Towns” special issue and the yearlong “Hooked” series exploring Vermont’s opioid crisis. When she’s not editing stories, Routly runs the business side of Seven Days — overseeing finances, management and product development. She spearheaded the creation of the newspaper’s numerous ancillary publications and events such as Restaurant Week and the Vermont Tech Jam. In 2015, she was inducted into the New England Newspaper Hall of Fame.

Paula Routly came to Vermont to attend Middlebury College. After graduation, she stayed and worked as a dance critic, arts writer, news reporter and editor before she started Seven Days newspaper with Pamela Polston in 1995. Routly covered arts news, then food, and, starting in 2008, focused her editorial energies on building the news side of the operation, for which she is a regular weekly editor. She conceptualized and managed the “Give and Take” special report on Vermont’s nonprofit sector, the “Our Towns” special issue and the yearlong “Hooked” series exploring Vermont’s opioid crisis. When she’s not editing stories, Routly runs the business side of Seven Days — overseeing finances, management and product development. She spearheaded the creation of the newspaper’s numerous ancillary publications and events such as Restaurant Week and the Vermont Tech Jam. In 2015, she was inducted into the New England Newspaper Hall of Fame.

More By This Author

Latest in Media

Speaking of...

-

Media Note: Connor Cyrus Leaves Vermont Public

Jun 27, 2023 -

Soundbites: Make Music Day in Vermont, Rockin' Ron's Library Tour, and Saving Grace Beef With Lil Xan

Jun 8, 2022 -

'Eyesore: A Building Concludes' Appears in the Made Here Film Festival

Apr 20, 2022 -

'All the Traditions' Turns 25, BeUVT Is Born, and Madaila Return

Sep 22, 2021 -

The Charlotte Blues: Small Town Paper’s Editor Departs After Reporting Zoning Dust-Ups

Mar 23, 2021 - More »

find, follow, fan us: